Dream Finders Homes (DFH)

Small builder on the block, taking a page out of the OG's asset-light playbook

This is the third and final act in the homebuilding series, which started with an industry piece and was followed up with a deep dive on NVR (NVR 0.00%↑) . I’ll reference both preceding write-ups in this deep dive, so if you’re unfamiliar with the industry or NVR I’d recommend flipping back! You can find the full financial model below.

Introduction to DFH

Patrick Zalupski graduated from university with a finance degree in 2003, spent 18 months working at the corporate headquarters of FedEx, and then quit and moved back home to Jacksonville, Florida where he would help his mother in the realtor business. At the time, his stepfather was buying foreclosed homes, renovating them, and flipping them, and Patrick stepped in to help. In 2005, he flipped a property on his own, and then started a nine-unit condo project in the early days of the homebuilding winter before realizing that the single-family market was less volatile. According to this origin-story interview (link), prior to the recession they couldn’t:

“find a way into the [single family] market because the national builders were buying up 500 lots at a time. We saw an opportunity to finally get in at attractive prices because the market had corrected so significantly. We were buying homesites for $24k that had been selling for $80k two years before”.

In 2008, Patrick convinced the Clay County Housing Finance Authority (mandated with funding affordable housing projects) to give him and a partner a $200k loan, and then convinced a developer to give him three lots without having to pay for the homesites until after the homes were sold – in essence, they were building homes with someone else’s capital. Dream Finders Homes (DFH 0.00%↑) was born. From 2009-2011 they built homes with these unusually attractive terms in Jacksonville, which was only possible because the housing market had imploded. They eventually got a traditional bank facility in 2011 and could move beyond dedicated affordable housing projects. They built 27 homes in 2009 and ramped up to 261 homes in 2012 before Patrick ended up buying his partner out in 2013. Since Patrick and his partner had very little of their own capital, they effectively stumbled into a model nearly identical to NVR whereby they didn’t own any land/lots on their balance sheet – most of their controlled inventory has typically been secured with option contracts, which required the least amount of capital investment per controlled lot. Looking back, Patrick notes that:

“NVR is the gold standard of a home building company… we don’t own any land on our balance sheet, just like them”.

DFH has always focused on entry-level homes in large production communities and has historically had ASPs <$400k (similar to Ryan Homes, the entry-level division of NVR). Unlike NVR, who has the most standardized entry-level offering in the market, DFH is more willing to customize features for buyers. I’ll expand on the implications of this approach later, but Patrick notes:

“When you start a company in the depths of a recession, you have to do whatever it takes to be successful. So, if a buyer came and said ‘I found this online’, or ‘I want to use this sink from Home Depot’, we were going to do it. It’s just a core value of the company. We have a very small custom home division. But if someone comes into our production communities, they can literally get a price request for a custom feature from our purchasing team. We make them put up nonrefundable money, around $300, to make sure it’s something they really want to do. About 5% of our customers do this. And once we’ve done something the first time, it’s easy to make a standard option… we always try to give more bells and whistles than the competition for the same or less price. ‘More features for less money’ is still the slogan we use today. It’s a delicate balance of price and quality”.

By offering more features for less money, leveraging some existing developer relationships, and taking advantage of a homebuilding industry in shambles, DFH organically expanded into Savannah, Georgia in 2013 (their first market outside of Florida, but a mere 2-hour drive from Jacksonville). From 2013-2018 DFH organically expanded into 7 markets, which included Denver, Austin, Orlando, and Washington DC (including the neighboring areas in North Virginia and Maryland). Following this organic expansion, DFH closed on 1,408 homes in 2018, making them one of the largest private homebuilders in the country. In 2019, DFH started what would end up being a 3-year M&A spree, acquiring a builder in each of South Carolina, North Carolina, Florida, and Texas (more on this later). To help fund this growth (both the M&A and organic acquisition of option contracts), DFH completed an IPO and preferred equity issuance in 2021. Access to new growth capital wasn’t the only impetus for going public. In a letter to shareholders two years ago, Patrick notes that going public allowed DFH to amalgamate over 30 different fully secured credit facilities into one single unsecured credit facility:

“This was arguably the #1 reason for DFH to complete an IPO. Our team was managing over 30 different fully secured credit facilities with tremendous friction costs due to the inefficiencies of having to appraise and secure each individual home or homesite prior to acquisition. These processes slowed down funding and significantly impacted our sale to start timeline. Ongoing funding was based on regular draw schedules as we built homes, which severely affected the payment timing to our vendors and land sellers, putting us at a constant disadvantage to peers. BofA, who led our IPO, agreed to provide DFH with an unsecured credit facility of $450mn, which subsequently increased to $817.5mn. Not only was the loan rate significantly lower than our traditional facility, but this consolidated all 30+ credit facilities into a single unsecured revolver. It is nearly impossible to overemphasize the efficiencies gained, which will allow DFH to turn our inventory more rapidly, resulting in better returns to shareholders along with more loyal vendors and land sellers who are now paid timelier. This single facility also lowered our overall cost of capital we estimate roughly 200 bps or more.”

The new facility is technically unsecured (although tied to a borrowing base which is dependent on inventory levels) and charges interest at SOFR + ~3.0%. By comparison, their 2020 facilities had a weighted average rate at SOFR + 3.5% but frequently had a “greater of” function that set the floor much higher than where the floating rate would have ended up (hence the meaningful reduction in the weighted average interest rate with this new facility). DFH was also utilizing some fixed-rate lines at 10%+ rates.

DFH is now the 13th largest public homebuilder in the country with 0.67% market share of total single-family construction in 2022, up from just 0.17% in 2018. They’ve grown faster than just about any other large builder over the last decade on the back of strong organic growth and M&A, although that’s off a small base. Exhibit A shows DFH controlled lots and new orders by geography from 2018-2022, and it’s important to recognize that DFH has increasingly diversified their end markets over this period. Jacksonville and Orlando are still their two most important markets (30% of 2022 completions), but they have a growing presence in Texas, the Carolinas, and Colorado.

One reason DFH has realized such high organic growth is that they’ve targeted markets with some of the highest population growth in the country. Their biggest markets like Jacksonville, Orlando, Texas (Austin, Houston, Dallas, San Antonio), Denver, and the Carolina’s all rank extremely high from a population growth perspective. If you recall from Part 1 of the homebuilding series, the smallest change in population growth rates can have a very large impact on demand for new housing. All else equal, I think DFH is uniquely exposed to a subset of markets that should see more resilient homebuilding demand than the national average over the next decade.

Complimentary businesses and business interests

In addition to homebuilding, DFH owns a title business and a 49% interest in a mortgage origination business called Jet Home Loans (with an option to acquire the remaining 51%). They also own a 49% interest in DF Capital Management, which is:

“an investment manager focused on investments in land banks and land development joint ventures to deliver finished lots to us and other homebuilders. We believe our relationship with DF Capital allows us to act quickly as lot acquisition opportunities are presented because DF Capital generally provides for faster closings and is not subject to the time delays that we have historically experienced when seeking financing for each project”.

DF Capital has raised two funds with outside equity:

Fund I was fully committed in early-2019 and had total committed capital of $36.7mn, of which DFH directly contributed 3.8%. DFH’s directors, executive officers, and other members of management invested 23.8% of the total committed capital in Fund I (this is a related party transaction). The general partner of Fund I is DF Management GP, of which DFH has a 25.8% interest, and other members of DFH Investors (including some directors and members of management) control another 65% of the general partner. At the end of 2020 and 2021 Fund I represented 6.7% and 1.0% of DFH’s total controlled lots respectively (they stopped reporting this in 2022, likely because it was so small).

Fund II was launched in 2021 and was fully committed by January 2022 with $322mn. DFH controls 72% of the general partner and receives 72% of the economic interest, but only contributed 0.9% of the capital ($3mn), while another 41.6% of the fund capital came from a handful of directors and executive officers (largely through a real estate private equity firm owned by one of the directors). At the end of 2021, Fund II represented 9.2% of DFH’s controlled lots (again, they stopped reporting this in 2022, but the share of controlled lots from Fund II is certainly lower).

I don’t love the related party transactions, but I also think that the good outweighs the bad, with the good being that DFH effectively has a sticky land banking partner to support lot acquisition, gets GP economics on the funds (1% management fee and 10% carry), and doesn’t have to invest material shareholder equity to get this source of supply. I’d also note that the relative investments by management in both funds is dwarfed by comparison to the size of their equity position in DFH. In his 2021 letter to shareholders, Patrick says:

“DF Capital Management is one of numerous great relationships we have with developers and land bank partners across the country, and will likely never be more than 25% of our land under option. Our many partnerships enable DFH to retain flexibility and be nimble when market conditions require…. Fund I is in its final distribution stage and currently tracking an 18%+ after fees IRR, in-line with our return target for Limited Partners… we are excited about these deals and the returns they will generate and believe Fund II will serve as a launchpad for future real estate funds of increasing size and scope. While we have zero operational control, DFH is entitled to a significant portion of carried interest which should create meaningful value for our shareholders in the future.”

To-date, neither Jet Home Loans or DF Capital have required significant investments or returned significant capital to DFH, but there is clearly upside potential from the GP ownership in these funds without any meaningful downside to DFH shareholders. As I understand it, DFH now expects to raise a third fund through DF Capital with well north of $1.0bn in commitments. Depending on things like fund performance and size, that third fund could contribute $10-30mn/year of additional FCF to DFH if they continued to get a ~70% economic interest in the GP – by comparison, DFH’s headline EBIT in 2022 was $356mn, while normalized run-rate EBIT is probably closer to $200mn.

Asset-Light Playbook

As I discussed in the NVR deep dive, most of the invested capital required to run a business like this is NWC (PP&E is negligible), and NWC largely consists of land/lot investments, construction-in-progress, and finished homes. The best way to reduce NWC is to avoid holding controlled lots on your balance sheet and instead control those lots via option contracts. With lot options, the builder would typically put something like 10% of the finished lot value down as a deposit, which they’d lose if they don’t exercise the option, but ties up way less capital to secure a lot backlog and leads to better ROIC through the cycle.

Like NVR, DFH relies heavily on option contracts to secure their lot backlog (more than any other large public builder aside from NVR). At the end of 2022 they controlled 43,558 lots but owned just 5,943 of those lots directly, and 68% of the lots they did own had homes being built on them. As such, DFH deploys very few dollars of NWC per controlled lot and generates amongst the best ROIC in the public peer group (Exhibit C; lower operating margins resulted in lower ROIC than DHI despite less capital deployed, but I’ll touch on that later).

Despite pursuing a similar strategy to NVR with option contracts, it’s worth pointing out that DFH deploys proportionally twice as much NWC as NVR. In Exhibit D I compare two different inventory categories as a percentage of revenue for NVR, DFH, and two other large builders. The first takeaway is that DFH clearly ties up much less capital than more conventional builders in land/lots because of their option strategy, but still ties up more capital than NVR. While NVR almost exclusively purchases finished lots with option contracts, DFH uses finished lot options and land bank option contracts. With the latter, they acquire land via option contracts and bid out the land development function to site contractors at fixed prices – this ends up tying up slightly more capital than a strategy exclusively focused on finished lot option contracts, and DFH ends up owning more vacant land/lots on their balance sheet than NVR. The second takeaway is that DFH’s CIP/Finished Home turnover appears to be at the low end of conventional builder comps and significantly lower than NVR. However, the DFH numbers get obscured by the impact of M&A, and when I attempt to normalize for that their CIP/Finished Home turnover is actually closer to industry averages.

One reason that NVR has such high turnover of CIP/Finished Home inventory is that they don’t build any spec homes, and so don’t get stuck with as many finished homes yet-to-be-sold. Another reason is that NVR has a very standardized offering with few customization options, which likely means that the construction window is shorter than builders that allow for more buyer choice. Finally, since NVR has vertically integrated with production facilities and can use those facilities to manage logistics and direct-from-manufacturer purchases, I suspect they have fewer contractor-related delays in construction. By comparison, DFH does build some spec homes, which seems to be an explicit trade-off between selling more units and ROIC (spec homes are some mid-single-digit percentage of completions, so it’s not a big deal). They also offer more customization options than NVR, where “we always try to give more bells and whistles than the competition for the same or less price”. Finally, DFH has not vertically integrated, and from my conversations with the company they have no intentions to do so. Where NVR seems to prioritize capital efficiency over everything else, it looks like DFH is taking a more balanced approach with an emphasis on both capital efficiency and organic growth. That helps explain why they’ve been one of the fastest growing homebuilders of the last decade and are now one of the top 3 largest builders in a handful of metros like Jacksonville and Orlando.

In any event, the asset-light playbook is a clear differentiator for DFH relative to most other large builders and is a key contributor to exceptional shareholder returns. With a high degree of confidence I can say that this is a strategy they will stick with.

Margins

In the NVR piece I outlined why scale matters – mostly at the regional level – and how it can lead to better operating margins. Exhibit E shows operating margins for DFH and the public peer group, where I’ve also included DFH’s operating margin adjusted for capitalized interest (DFH tends to capitalize close to 100% of their interest expense, which isn’t typically the case with the other large builders). Unsurprisingly, the five largest single-family builders in the country have the highest operating margins. These builders tend to have dominant market share in most of their largest metros. Also unsurprising is that DFH, as one of the smallest public homebuilders in this peer group, has amongst the lowest operating margins.

While DFH was the 2nd largest builder in Orlando (mid-teens market share) and the 3rd largest builder in Jacksonville (mid-teens market share) last year, they didn’t even register among the top 10 in many of their other metros. For example, DFH completed significantly fewer homes than the 10th largest builder in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, Austin, Savanah, Raleigh, and Washington, DC. In my view, they have yet to reach sufficient regional scale in many of their metros to achieve operating margins comparable to some of the larger builders. DFH reports net margins by segment (which is generally divided into geographies) and Exhibit F shows 2022 net margins and 2022 completions/metro. Their biggest metros are clearly generating the best margins, and my research suggests that margins in Jacksonville are comparable to those of other large builders.

So, the next question becomes, can DFH eventually bring margins in other metros up to where they are in Jacksonville? I’m not sure that’s easy to answer, but there is evidence that DFH margins (absolute margins and relative to industry median) do improve as they scale up in a metro, and they’ve shown that they can scale up both organically and through M&A. One year after DFH organically entered Denver (2014) they built a mere 9 homes and generated just 10.3% gross margins. That was a full 10% lower than the industry median at that time. In 2022 DFH completed almost 300 homes and generated gross margins above 23%, which was only 2% lower than the industry median. They’ve been able to organically take share in Denver, and it looks like they were the 11th largest builder in that metro last year. Similarly, one year after DFH organically entered Orlando (2015) they completed some small number of homes and generated gross margins of just 5.5% (14% lower than the industry median). In 2022 they completed more than 600 homes (thanks in part to an acquisition in 2021 that doubled their presence) and generated gross margins of nearly 19% (just 7% below the industry median).

I also looked at Top 10 builder share in each of the 50 largest metros in the country (Exhibit G). DFH’s largest metros like Jacksonville and Orlando are already fairly concentrated with the top 10 builders holding down 80% market share. Many of the top 10 builders in those metros are the large public competitors, and I suspect there is little room left to take share organically or through M&A. Thankfully, DFH already appears to have achieved sufficient regional scale in those markets and is generating reasonably strong margins there. But in Texas (Austin, Dallas, Houston), the Carolina’s (Raleigh, Myrtle Beach, and I presume the other metros not listed in the top 50), and Denver, there is significantly less concentration among the top 10 builders. It just so happens that some of the least concentrated large metros happen to be places where DFH operates but hasn’t yet reached significant scale and is currently generating meaningfully below-average margins. Against that backdrop, I think there is a reasonable chance that they can A) organically take share from the long tail of small builders, and B) acquire more regional builders. If they successfully do either of those two things than I think there is a path to generating much higher corporate margins – at the very least, DFH margins should move closer to industry medians.

Another reason for below-average margins is that DFH has been very acquisitive in recent years and there is likely some transition period following M&A where margins are lower than where they should end up once acquisitions and brands are fully integrated. Part of the reason is that acquired companies continue to operate autonomously under their own brand immediately after an acquisition, often alongside a legacy-DFH homebuilding unit. For example, DFH had organically entered Austin, Texas back in 2015 but acquired another Texas-based builder called MHI in late-2021 (Austin, Houston, Dallas, San Antonio), where MHI continues to operate separately from the legacy-Austin business (if you go to the DFH website, Austin is the only Texas-based metro you can buy from under the DFH brand). Management indicated that they expect to convert all brands and geographies under a single umbrella eventually. Most of the MHI executive team has stayed on and I’m told the MHI CEO has committed to stay on for four years. I was also told that MHI SG&A intensity was much higher than the rest of the DFH business when it was acquired, but that there was room to improve over time. In the 17 months following acquisition, net margins in the Texas segment (which is just MHI, because legacy-Austin is included in Other) have increased almost linearly from 6.04% in the first quarter post-acquisition to 10.41% in 4Q22 – increasing much more than the corporate average, and much more than the industry median. That above-average improvement lends some credibility to the statement that SG&A intensity was high but should improve in the years post close.

Finally, when I spoke with management late last year, they indicated that they were exploring organically entering new markets like Tampa (close to their home base), Atlanta, Salt Lake City, and Nashville. Most of these metros were just on their wish list, but they had already started organically building out in Tampa. The last time they organically entered a metro was Washington, DC in 2017. In the first full year operating in that metro DFH only built 15 homes and generated -23.52% net margins! In 2019, they built 76 homes and still generated a -6.94% net margin, which was dilutive to overall corporate net margins to the tune of 70 bps. It wasn’t until 2020 when they built 232 homes that net margins turned positive, coming in at 4.07%. To the extent that DFH is in the early innings of organically expanding into new markets, we should expect that this will be a drag on overall margins, but that margins should improve as they continue to scale. Notably, many of the metros on their wish list are much less concentrated than other large markets. For example, the top 10 builders in Nashville and Atlanta had lower share than almost every one of the other large metros on the Builder Online Local Leader List, and both markets were massive with roughly 10k and 20k homes being built/year respectively.

In my view, there are plenty of reasons to expect DFH margins (both absolute and relative) over the next decade to improve from what we’ve seen over the last five years. It's also worth reiterating that despite DFH generating amongst the lowest operating margins in the peer group today, their ROIC is still industry-leading ex. NVR. That’s all thanks to their asset-light approach to securing lot backlog, and it’s hard to overstate how big of a differentiator that approach is. The profitability of their existing business makes it more palatable for DFH to target new markets where margins are initially bad (and often negative).

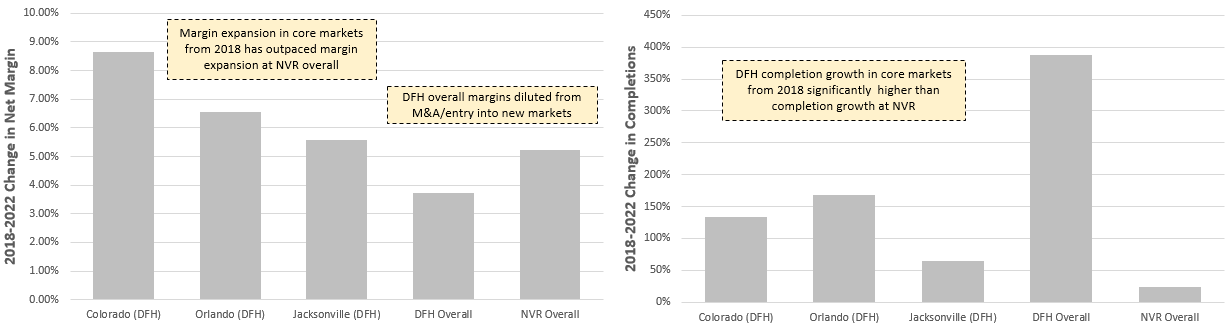

To wrap up this section, I wanted to show some of the historical data informing my thesis that DFH margins can expand as they scale in each metro. That’s challenging to do with the information we have, but in Exhibit H I show the change in net margins from 2018-2022 in some of the core markets DFH already had a presence in during 2018 versus the change in net margins at DFH and NVR overall (I chose NVR as a proxy for industry margin expansion for a builder pursuing a similar strategy but already at scale). I also show the change in completions for both businesses and these core DFH markets. We can clearly see that net margins in Colorado, Orlando, and Jacksonville expanded faster during this period than net margins at NVR overall. We can also see that growth in completions in these markets was orders of magnitude higher than growth in completions for NVR (and the industry). Finally, despite this regional margin expansion, DFH margins overall expanded by less than NVR, which is almost entirely attributable to the fact that they acquired plenty of businesses during this period with lower margins (at least initially). In my view, this illustration is supportive of the thesis that DFH margins (both absolute and relative) should expand as they scale, and their track record on that front is pretty good.

M&A

M&A has clearly been a big component of the strategy in recent years, and I suspect DFH will continue to be acquisitive in the future given the clear relationship between regional scale and margins. M&A often gets a bad rap, but DFH’s track record to-date is great. Here is a quick summary of the businesses they’ve acquired in recent years:

Village Park Homes acquired in 2019 for $24mn (South Carolina)

H&H acquired in 2020 for $44mn (North Carolina and South Carolina)

Century Homes acquired in 2021 for $36mn (Orlando)

MHI acquired in 2021 for $582mn (Texas)

In Exhibit I I’ve show the purchase price allocation from aggregate M&A since 2019. In aggregate, DFH effectively just paid for inventory value. This is largely construction-in-progress inventory, so it turns over a few times per year and therefore monetizes very quickly.

I don’t know exactly what operating income or net income from these businesses were at the time of acquisition, but I can make an educated guess. Using some proforma information provided in the 2021 annual report (which gives us an estimate of 2020 contributions), I’d guess that these four businesses might have generated about $60m in net income if they weren’t owned by DFH. In aggregate, these businesses carried very little debt at the time of acquisition, but we know that DFH likely borrowed ~70% of inventory value on their construction line of credit to fund these deals (I’ll touch on leverage in a minute). So, it’s likely that DFH equity capital that went into these deals was more like $321mn (including contingent consideration) and that net income, adjusted for the additional interest expense, was closer to $45mn. That would take the weighted-average acquisition multiple to 7.0x on 2020 adjusted earnings. DFH also completed a sale-leaseback on 93 model homes which freed up some capital with a modest incremental lease cost and takes the weighted-average acquisition multiple to just 6.4x on 2020 adjusted earnings. But using 2020 adjusted earnings likely overstates the multiple paid. The MHI acquisition was completed at the end of 2021, and in the first 4 quarters after close DFH reported $92mn in net income from that business which would translate to a 3.4x forward P/E (using the same leverage adjustments). You’d think that they had some line-of-sight to that net income given the fact that all builders have a backlog of customer commitments and homes-under-construction, which makes the deal metrics that much more impressive. With the H&H acquisition it looks like DFH paid ~2x N12M P/E (using the same leverage adjustments). My analysis suggests that the payback period (on equity) for all these deals is likely to end up being less than three years, even if the housing market turns in the near future. That’s wild considering the 10 largest builders have typically traded at >10x P/E over the last decade, and no single builder in that cohort had traded below 5x since the GFC.

A lot of assumptions were required to back into that P/E estimate, but however I slice this analysis it looks like DFH should earn some multiple of their cost of equity while simultaneously expanding their footprint in some of the fastest growing states in the country. When I spoke with the management team, I was told that they are very selective when it comes to M&A and that they regularly evaluate and reject acquisition opportunities for not meeting their hurdles. It’s hard to discern if that’s just lip service to good capital allocation or they just got lucky here with deals that they could close, but if you take those comments at face value then you’d conclude that this management team does have some capital allocation prowess. And I’m inclined to take those comments at face value given a track record of 4 very solid acquisitions, but more importantly, zero transactions getting completed during 2022 when the industry was likely overearning and seller expectations would have been high. It’s the combination of very accretive deals and restraint that gives me confidence that they’ll continue to deploy capital via M&A at attractive returns.

One of the most obvious synergies that DFH can realize almost immediately when they acquire a small private homebuilder is to consolidate multiple secured facilities under their one unsecured line. Recall that one of the driving forces behind their decision to IPO was exactly that:

“This single facility also lowered our overall cost of capital we estimate roughly 200 bps or more”

Not all targets utilize leverage, but for the ones that do it seems likely that DFH can increase inventory turnover and lower debt funding costs post-close. For example, H&H had debt equivalent to 80% of their inventory value. If DFH could reduce that cost of debt by 200 bps, they’d improve net margins by more than 100bps. That’s a big deal for a business that looked to be generating just 4-5% net margins to begin with. Layer in a modest improvement in inventory turnover and the acquired business would generate a much higher ROE post-close. With interest rates increasing so rapidly over the last twelve months, and homebuilding activity/ASP/margins seemingly rolling over, I suspect that there will be plenty of opportunities for DFH to acquire levered private homebuilders in the next 1-2 years.

And there should be plenty of acquisition targets. In most metros that DFH operates in or has on the wish list I can see multiple private builders in the top 10 that are smaller than MHI. As I mentioned previously, plenty of these markets also have relatively low concentration among the top 10 builders, so there should be dozens of small builders comparable to Village Park Homes or Century Homes beyond the top 10 list.

In my view, it’s not a question of whether DFH can find acquisition targets at attractive prices, but rather do they have the financial capacity to complete M&A, which is a good segue into the next section.

Balance Sheet and Funding

DFH has always relied on credit facilities to partially fund the NWC required to run this business, specifically they borrow to fund home construction (the period of time between putting a hole in the ground and selling the house). The capacity of their current facility is tied to a borrowing base which is a percentage of net book value under various inventory categories. For example, DFH can borrow up to 90% of the net book value of presold housing units at the high end, and up to 70% of the net book value of finished lots. The vast majority of DFH’s inventory is presold housing units under construction, so the weighted-average ceiling under this facility is something like 85-90% of the book value of inventory. There are a handful of covenants that restrict their borrowing like a debt-to-cap ratio, interest coverage ratio, absolute tangible net worth value, and so on, but they were well in the clear on all these covenants in 2022. In fact, even if operating income fell by 70% in 2023(!), they’d still be onside with all these covenants (in part, because debt levels ebb and flow with CIP inventory which itself is countercyclical).

Exhibit J shows Debt/Inventory from 2018-2022 (year-end) vs the weighted average ceiling in place today. From 2018-2020 Debt/Inventory was ~60% but increased to 71% in 2021 because DFH tapped the line to fund acquisitions (most notable being MHI). Even still, DFH has slightly more than $200mn of remaining capacity today.

I can see how some investors would look at a headline Debt/EBITDA metric of 2.3x on 2022 EBITDA (when the industry was arguably overearning) and get the jitters. But I’d argue that a metric like Debt/EBITDA overstates the risk from leverage in this case because all this debt is effectively secured by CIP inventory that monetizes within 3-6 months. If DFH sold 20% fewer homes next year, their CIP inventory would fall as they sold homes and they could use part of the proceeds to pay down debt. If operating margins were even modestly positive, they’d still accrue cash and remain onside with their borrowing base and all covenants. Depending on the leverage metric used, DFH might stand out as an outlier (with excessive leverage), but when I ranked all the builders on Debt/CIP-Inventory DFH was roughly in-line with the industry average.

It's also worth highlighting that DFH is sitting on a record cash position. In Exhibit K I show Net Debt/Inventory vs the borrowing base ceiling, and total cash in both absolute terms and as % of total capitalization. Part of the increase in cash during 2021 was a function of IPO proceeds, but 2021/22 CFO ex. NWC changes was also very strong on the back of higher unit volume, ASPs, and margins – leading to significant cash accrual over the last two years.

Today, DFH is sitting on $365mn of cash (28% of their current market cap) with plenty of capacity on their facility. Regardless of what happens with the broader economy and the homebuilding industry in the next two years I think they have plenty of breathing room to continue pursuing M&A and/or leaning into organic growth. Recall that during the GFC, NVR was able to aggressively take share because of their strong financial position. I’m inclined to think that DFH would be in a similar position today if the homebuilding market turned this year.

DFH did issue $150mn of convertible preferred shares in 2021 to help fund the MHI acquisition. Those prefs charge 9.0% and are convertible beginning in 2026. The conversion price is a 20% discount to the 90-day average closing price with a floor of $4.00/share. In the draconian scenario that those prefs convert at $4.00/share in 2026, existing common equity holders would get diluted to the tune of roughly 30%. The management team has been very explicit about intending to call the prefs prior to the conversion date, and I suspect part of that large and growing cash balance is earmarked for just that purpose. In my view, the probability that those prefs convert is extremely low, and I’d think about true cash available for reinvestment/distribution as being closer to $215mn – still 17% of the current market cap where the $150mn delta goes toward reducing interest expense by $13.5mn/year.

Ignoring the prefs, all of DFH’s interest expense is floating rate, and with rates moving higher over the last twelve months that debt service cost has also increased. Since DFH capitalizes the vast majority of that interest expense, higher interest rates will reduce headline gross margins and operating margins. By my math, 2023 margins should compress by close to 100bps because of higher interest rates (all else equal). For a business that generated headline operating margins of just 10.4% last year (12.8% before capitalized interest and contingent consideration revaluation), that 100bps hit is notable. Does this suck? Yup. Is it manageable? Absolutely. I think it’s important to stress test the business/balance sheet for a recession scenario to better understand the risk (or lack thereof) of their current capital structure, but I’ll circle back on that at the end.

One final thing to highlight here is how much this inventory-backed leverage has improved return on common equity. ROIC was already amongst the highest in the peer group excluding NVR, but return on common equity is nearly twice as high, even with the enormous cash drag (return on common equity excluding cash would have been >100% last year). In fact, DFH’s return on common equity is routinely the best in industry.

Management, Governance, and Culture

Patrick Zalupski (41 years old) is still the President, CEO, and Chairman of the Board. He’s also on the investment committee of DF Capital and on the board of Jet Home Loans. One thing I find particularly appealing about Patrick is that he’s never taken money off the table since founding DFH 15 years ago, which shows a lot of confidence in the business:

“Just like the previous three times the Company raised capital, 100% of the proceeds [from the IPO] were re-invested in the business with no shareholder taking anything off the table”

Today, DFH has 32.5mn Class A shares and 60.2mn Class B shares, of which 100% of Class B shares are owned by Patrick, and 27% of Class A shares are held by Patrick and other executives/directors. In aggregate, the executives/directors of DFH own 75% of the economic interest in the business and control 90% of the votes (Patrick specifically has roughly a 65% economic interest and controls about 85% of the votes since Class B shares entitle him to 3x as many votes as Class A shares). Even in the unlikely event that the prefs convert to Class A shares, Patrick would still control a majority of the votes and retain most of the economic interest.

Given Patrick’s control and age, shareholders in DFH are ultimately making a bet on Patrick and his ability to manage this business to the benefit of all shareholders for what will likely end up being a couple more decades. If that’s the case, I think there are two important questions to ask: 1) is Patrick a great operator, and 2) is Patrick a great capital allocator.

On the operator front, Patrick quite literally built this business from scratch, and grown it into one of the largest homebuilders in the country. He’s also worn just about every hat you can wear in this business – he’s put-up drywall, negotiated land deals, secured financing, and managed an ever-growing organization with all the people-related challenges that comes with that. Part of his strategy has been making sure that DFH emphasizes mutually beneficial relationships with partners, which ensures that they can continue to utilize option contracts to secure lot backlog and increase share:

“Lastly, relationships are the foundation of DFH. We work extremely hard to build long term partnerships with everyone who does business with DFH. We have land sellers from whom we bought land in 2009 and are still doing deals with today, which is a testament to our culture and the way we do business. We have plumbers, electricians, and framers we supported when they were just getting their businesses who have growth beyond their furthest expectations. We constantly strive to find win-win solutions for all parties, and we can only be successful in the long term if our land and trade partners are also successful. It is a lot more efficient and profitable for both sides to replicate similar transactions many times versus a ‘one and done’ scenario. Maybe one side was able to squeeze a few more dollars out of the deal, but if that’s the last deal between parties, who really won? We try to apply this approach to every aspect of our business. We want to be the preferred partner to work with in all aspects of home building as we believe that to be the winning approach”

That approach might leave more money on the table (lower margins and slightly higher capital intensity) than a builder like NVR, but it certainly helps with organic growth if they can do more deals and get into more communities. Couple this approach with their slogan of “more features for less money”, and it’s clear they work hard to have a compelling value proposition to both suppliers and customers. Overall, I think Patrick is an excellent operator and DFH’s track record supports that view.

Even though Patrick wears a lot of hats, I think it’s pretty clear that he’s also done a good job at delegating and providing employees with autonomy. DFH has nearly 20 “market presidents” who are basically the operators in charge of each metro. Each of these presidents seem to operate little autonomous business units that must compete for capital from the head office, where a dedicated land pipeline VP pitches land deals to the Land Committee twice a month. That Land Committee, which consists of the CEO, COO, CFO, and a few other executives, ranks deals based on metrics like velocity of sales, margins, IRR, and risk, where only the best deals get funding. In addition, the presidents in each market have compensation linked to the P&L of their specific market in conjunction with 10 other KPIs that include ROE, asset turnover, margins, and customer survey scores. As a public entity, 30-40% of these managers annual bonuses are now in the form of 3-year equity grants. Below those market presidents, DFH regularly reviews incentive plans for all employees and crafts very particular incentives to drive the behavior they want to see for a given role. For example, a permitting coordinator might get paid $10 for every permit they secure. I get the impression that a lot of thought goes into making sure everyone is rowing in the same direction to maximize the KPIs that drive return on invested capital and reinvestment rates.

On the capital allocation front, I think the M&A record, asset-light approach, and employee incentive programs all speak for themselves (these are all Patrick-led decisions). Beyond that there are plenty of examples where DFH did something unique to improve returns to equity holders, but the best way to understand how Patrick thinks about capital allocation is to read this section of his 2021 annual letter to shareholders (emphasis my own):

“A good example of how we focus on generating the highest returns on capital was the construction and sale/leaseback of our corporate headquarters, located in Jacksonville, Florida. In 2014, DFH acquired three land parcels for a future office (it is difficult to find suburban office space in Jacksonville so we decided to design and build it ourselves). We felt like the $750,000 acquisition price was attractive, which included entitlements for over 150,000 square feet of office space. We ranked the parcels 1, 2 and 3 regarding marketability for sale and decided to keep parcel 2 for our future offices. We sold parcel 3 in 2016 for $550,000 and sold parcel 1 in 2018 for $750,000. The cost to build our entire headquarters, including land, was approximately $10.4 million and we had approximately $4.6 million of that in DFH cash/equity. Once completed, we decided to test the market to see what a sale and leaseback would yield, and we were pleasantly surprised to ultimately close at a suburban office record price of $13.7 million. This allowed DFH to generate a pre-tax profit of $3.3 million in the building sale and free up an additional $4.6 million of equity capital, $8.8 million in total, to be re-deployed towards a higher and better use. By generating $3.3 million of pre-tax profit while utilizing $4.6 million of equity capital we generated over 60% of ROE on a pre-tax basis, which, on our much lower company capital base at that time of $54.2 million was very meaningful. If, for example, we took the $8.8 million of capital and invested it at a 20% rate and continued to reinvest those earnings at the same rate, we would generate an extra $104 million of pre-tax net earnings over the next 15 years — the duration of our lease. That is the magic of compound interest. Everything we do at DFH is directed towards driving the highest and best returns for each dollar of capital we invest. We are largely agnostic as to whether these returns are generated organically, via acquisition, or through an asset sale as discussed in the previous example. We have historically grown organically and believe we will continue to do so for numerous reasons, but we have also completed four successful acquisitions that effectively returned all invested capital, or are on target to do so, in under three years from acquisition closing. The greatest part of these acquisitions is that we will control these businesses’ future earnings streams forever. Each acquisition brought invaluable knowledge that we will possess in perpetuity and will guide us in our future decisions. We want our operators who manage each homebuilding division — we have 14 in total —to compete for capital and not just assume we are going to invest in each of their deals. Some divisions will grow faster than others due to their outperformance and the best operators will receive the most capital. This competition for investment dollars will help ensure we are deploying our capital as effectively as possible because we care most about returns, not the vehicle used to get us there. This is our philosophy and how we have built this business over the past 13 years”

Just about everything I’d look for in a good capital allocator was conveyed in that passage. In my view, an investor in DFH can rest easy knowing that the single largest shareholder (and controlling shareholder) is thoughtfully evaluating every lever that can be pulled to generate value for all shareholders. In my view, this combination of operational and capital allocation excellence is rare.

What is the market pricing in?

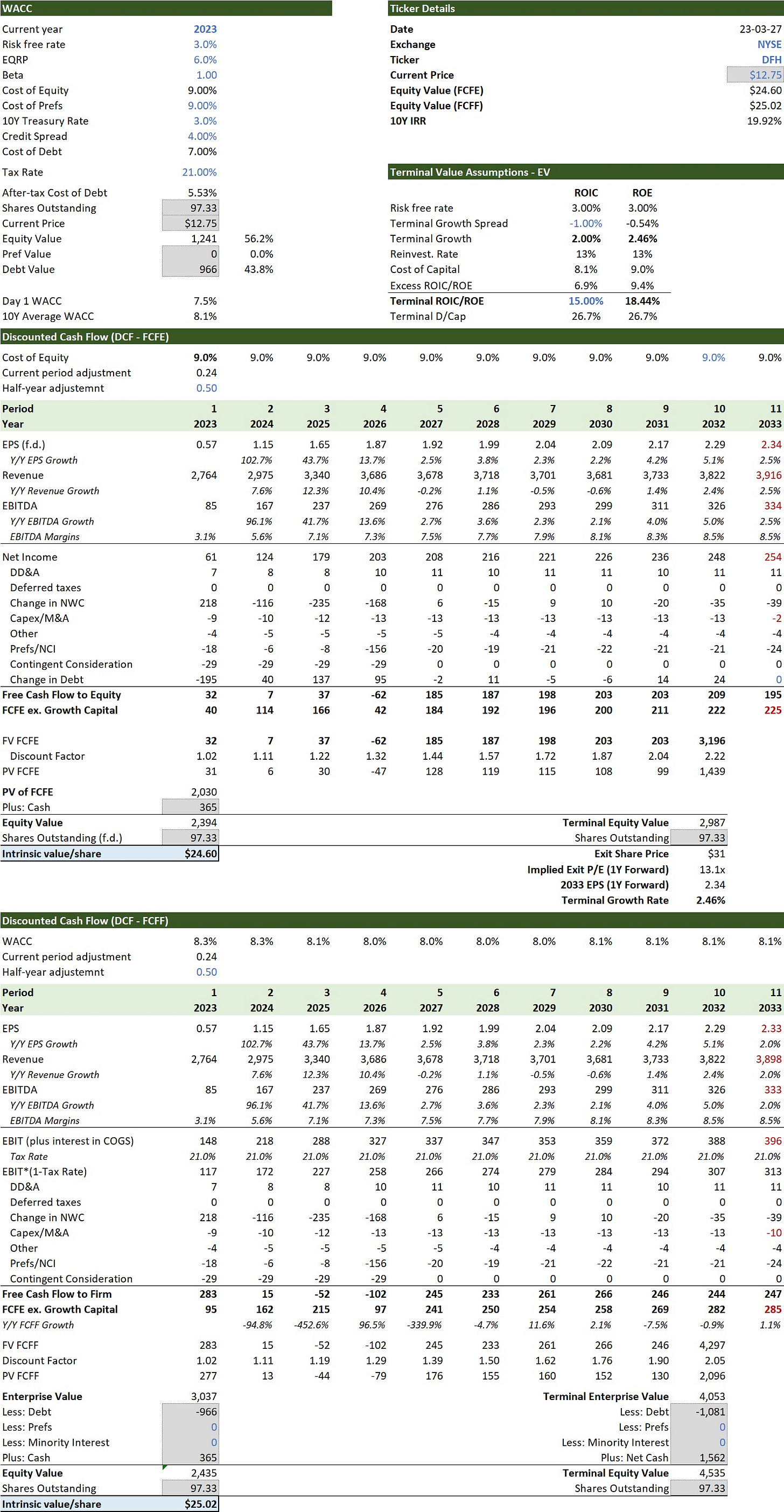

I think a good place to start with valuation is to back into what the market is pricing in for DFH. To that end, Exhibit M shows what I had to assume for key drivers in the model to arrive at a fair value estimate roughly in-line with the current price of ~$12.75/share.

To start, I took the average industry unit volume estimates from Exhibit I in Part 1 and reduced them by 5-6%. In that scenario, industry single-family completions peaked in 2022, fall significantly in 2023, recover modestly over the next few years, and then end the next decade at a run-rate that’s nearly 30% lower than 2022 completions.

I then held DFH market share constant through the entire period, which is extremely punitive considering:

DFH operates in markets with higher population growth than the country overall, and those market should therefore take some share nationally;

DFH has a history of organically taking share, and many of their existing markets are relatively unconcentrated; and,

DFH has historically been acquisitive (at good prices), has the financial capacity to continue being acquisitive, and has their sights set on markets with plenty of acquisition targets.

With flat market share, DFH completions also peak in 2022, and exit the next decade 28% lower than last year. That by itself wasn’t enough to back into the current price, so I also reduced 2022 ASPs by 15% by 2024 and then had them exiting the next decade lower than 2022 (in real terms, ASPs end up being nearly 30% lower than last year and lower than ASPs at any point from 2018-2021). Even that didn’t get me to the current price.

Next, I hammered margins this year and assumed it took until 2025 to recover (partly because of lower gross margins, and partly because of higher SG&A intensity as unit volumes fall). I then had to assume that margins compress modestly over time as unit volumes fall where normalized margins end up lower exiting the decade then they were at any point between 2018-2022.

The net impact of all this is adjusted EBIT (adding back capitalized interest) that falls by 65% from 2022 to 2023, and then exits the next decade lower than 2021 (they remain onside with all debt covenants through this period and don’t need to raise any additional equity). Assuming the exit assumptions are representative of mid-cycle earnings, I then applied an 11.0x P/E multiple to arrive at terminal value (I arrived at this exit multiple based on a terminal cost of equity of 9%, cost of debt of 7%, Debt/Cap of ~35%, ROIC of 8%, and terminal growth rate of 2%).

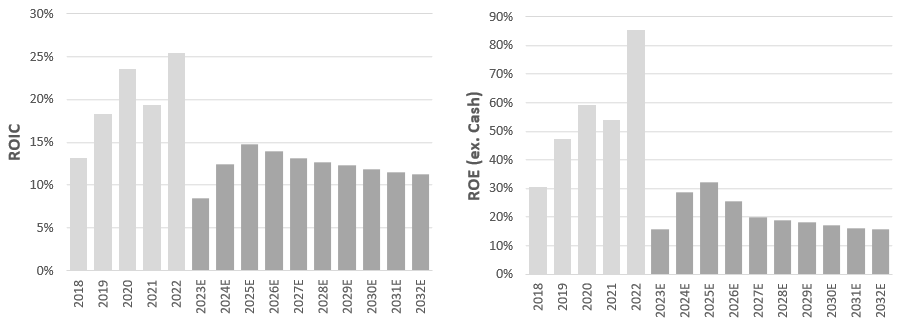

I made a few other small assumptions that increased capital intensity and Exhibit N shows the ROIC and ROE (excluding cash) that DFH would generate under these assumptions. Notably, both ROIC and ROE end up much lower than they’ve been historically. ROIC also ends up being pretty close to where median ROIC was for the public peer group from 2012-2020, despite DFH’s asset-light approach to this business. The implication is that industry-wide ROIC would probably end up being low-to-mid single digits.

In my view, the scenario laid out above is extremely punitive. If anything, this seems more representative of a bear case, and yet that’s where the stock trades today.

Another simple way to look at this is to compare current prices to 2022 earnings (Exhibit O). There is no question that 2022 was a big year where the industry was likely overearning, but I’m hesitant to use forward estimates in part because I think most of those estimates are useless and need to be revised anyway. Even still, I think the 2022 multiples are fine for a relative value comparison. In that comparison, DFH is trading near the low end of the peer group, despite an asset-light model that should compound those earnings at a higher return than most competitors (with less risk), a balance sheet that doesn’t look materially different than the peer group, a management team with significantly more skin in the game than most, a history of margin expansion, a history of accretive M&A (and the ability to continue doing that), and proportionally more exposure to the most attractive markets in the country.

Admittedly, it’s not immediately clear to me why DFH is priced where it’s at, aside from general concerns about the homebuilding industry – although that wouldn’t necessarily explain where DFH sits in the relative hierarchy. It could be that the float is small (a measly $2.0mn trades every day), and there isn’t sufficient liquidity for most large institutional managers to get interested. It could be because the risk of leverage is misunderstood. It could be that the company doesn’t do earnings calls and doesn’t have an IR team (nobody is out there pounding the table). It could be that there is almost no sell-side coverage (only 5 analysts). Maybe it’s a combination of all these things, or something else I’m missing entirely. If anyone reading this has a helpful perspective to share, I’d encourage you to reach out or comment below!

Base Case

It’s difficult to peg down a specific set of assumptions for a base case because the margin of error on some of the big industry drivers is high, but I’ll take stab at it anyway (see Exhibit P).

In the base case I use the same average industry unit volume estimates from Exhibit I in Part 1, and assume that DFH grows slightly faster on the back of A) stronger homebuilding demand in their core markets where population growth is higher than average, and B) some modest organic share gains in those same markets. Even still, I have DFH completions falling by a little more than 10% in 2023 and peaking a few years later before levelling off at around 7k units/year. Notably, I’m not including any new market expansion or additional M&A here. I think it’s highly likely that they continue to be acquisitive and pursue new markets, but I’m not inclined to pay for that.

I still assume that there will be some ASP compression over the next two years, but that ASPs inflate at a 3% CAGR from 2019-2032 (a more normalized starting year).

On the margin front, I think it’s fair to assume that they will compress in the near future, particularly if unit volume falls (I wrote an entire section on this dynamic in Part 1). Beyond the next few years, I think margins could expand modestly as they take share in existing markets and fully integrate past acquisitions. I take run-rate EBIT margins to 10%, which is slightly higher than the 2018-2019 period, and more consistent with full-cycle industry averages (although much lower than the likes of NVR through any point in the cycle).

Even in the base case, this all culminates in EBIT (adjusted for capitalized interest) falling by 65% in 2023 and never again hitting the 2022 peak. Assuming the exit assumptions are representative of mid-cycle earnings at that time, I then applied a 13x P/E multiple to arrive at terminal value (I arrived at this exit multiple based on a terminal cost of equity of 9%, cost of debt of 7%, Debt/Cap of ~25%, ROIC of 15%, and terminal growth rate of 2%). Over the last decade, the peer group has traded at 11-12x on average while NVR has traded closer to 16x.

In Exhibit Q I show what ROIC and ROE (excluding cash) would be in this scenario. ROIC shakes out at around 15%, which is almost twice as high as the industry average over the last 20 years, but makes sense given their asset-light approach and the modest EBIT margin expansion assumptions. ROE (excluding cash) ends up in the mid-to-high 20% range, largely because I think they’ll continue to borrow against CIP inventory.

Using these assumptions, I arrive at a fair value estimate of around $25/share, which is nearly double the current price of ~$12.75/share and would translate into roughly a 20% IRR over the course of ten years. You can find the full model behind my base case below, but I’ve also included a screenshot of the DCF output tab in Exhibit R.

Stress testing the model

While I do think that the implied expectations behind the current price are punitive and my base case is nearly double the current price, I think it’s important to stress test the model under a really draconian scenario.

In this draconian scenario I take industry-wide single-family completions down 40% from 2022 and have DFH losing modest share such that DFH completions fall by 45% from 2022-2025. At the same time, I have ASPs falling by almost 20% over the next two years, and I take EBIT margins down to just 2.0% this year, with a very slow recovery up to 7%. On the back of this, revenue falls by ~55% through 2025 and cumulative net income over the next three years is roundable to zero.

With these assumptions it looks like DFH would breach covenants on their facility, so they’d have to use most of their current cash balance to repay some of that debt and get back on side. It would be tight, but they’d also have just enough cash to call the prefs before they could convert (although I suspect by then they could just replace the prefs with another debt facility). The silver lining here is that NWC ends up being a very big cash inflow in this scenario, which is literally the only reason they’d stay afloat.

I’ve shown a summary of these assumptions in Exhibit S.

If I increase the cost of equity to 10% and reduce the terminal P/E multiple to 9.0x, I’d arrive at a fair value estimate of about $8.50/share (33% lower than the current price). I can’t emphasize enough how unlikely I think this scenario is. As I outlined in Part 1, it’s pretty clear that there is currently a housing deficit, and any meaningful reduction in completions today would have to be met with either A) a rapid and sustained increase in activity, or B) significant ASP inflation, which in turn would likely support margins. This draconian scenario has none of that – and fair value downside would still only be 33%. The more important reason for completing this exercise is to show that DFH would survive if any of this played out over the next 1-2 years. They wouldn’t run into a liquidity problem. They wouldn’t breach covenants. They’d be able to call the prefs. Against that backdrop, I don’t think there is any obscene risk of permanently impairing capital from today’s price.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that this is a cyclical industry and all competitors will see activity ebb and flow with that cycle, DFH included. There are also multiple reasons to expect that 2023 and 2024 could be challenging years for the industry (which I explain in Part 1). Nevertheless, I think expectations for key drivers implied by the current share price are extremely punitive and my base case is nearly 2x higher than the current price.

DFH is managed/controlled by what I consider to be a very strong CEO, has a good capital allocation track record, operates in some of the most compelling markets in the country, utilizes a relatively unique asset-light strategy that improves returns and minimizes risk, and appears to have an opportunity to deliver margin expansion off a more normalized level. They also have what I consider to be a very strong balance sheet, with nearly 30% of their current market cap sitting in cash. Even after stress-testing the model, I’m convinced they could weather a serious storm if there was a recession tomorrow, and likely come out stronger on the other side. In my view, the risk/reward at the current price is quite compelling if you don’t expect a full-blown housing Armageddon in the next 12 months.

As always, I encourage you to reach out if you disagree with anything in this piece or have any questions. You can reach me at the10thmanbb@gmail.com, in the comments below, or on Twitter.

Damn. Now I regret not reading this sooner. It already reached your intrinsic value in a span of few months! what do you think at this current prices? seems really frothy given your assumptions.

Nice work here. Another company has just become public and probably closest comp to dreams United homes. Symbol UHG. They growing quicker and have higher margins. Have you looked into ?