I’ve always found the homebuilding industry interesting. With a little capital, any Tom, Dick, or Harry can get into the business of building homes, and I’ve seen this happen first-hand almost a dozen times. The barriers to entry are relatively low, but the barriers to profitable and sustainable scale seem high. I’ve seen small fortunes made in this business, and I’ve seen a lot of builders go out of business after years – or decades – of success. It’s hard not to be drawn to these stories.

Ten years ago someone sent me an article about Norbert Lou and Punch Card Capital. A good deal of the article discussed Norbert’s investment in NVR Inc. (NVR 0.00%↑) back in the late-90’s. NVR was a relatively small homebuilder at the time and had a unique business model relative to your run-of-the-mill large homebuilder. I recall adding NVR to my long and growing list of businesses to study, and then I forgot about it and never circled back.

In 2021, nearly a decade after I’d first read about NVR, Dream Finders Homes (DFH 0.00%↑) IPO’d. I happened across a letter written by DFH’s founder/CEO, and immediately recognized that they were taking a page out of the NVR playbook. But unlike NVR, which at this point is probably well understood by the market, I thought DFH had a better chance of flying under the radar given the small float and lack of history as a public company. And that’s the impetus for this multi-part series. I originally intended to do a standalone deep-dive on DFH (now Part 3) but figured that a broader introduction to the industry (Part 1) and an additional deep-dive on NVR (Part 2) would help set the stage. So here we go. In Part 1 my objective is to provide a framework for thinking about industry activity, walk through the downside risk to completions, explore the competitive landscape, and look at homebuilder economics.

Housing Stock

I find it helpful to think about the housing industry through both the stock and flow lenses, and while flow is the direct driver for homebuilders, I think the best place to start is stock. In my view, there are three things to consider as we think about housing stock: population growth, adults/household, and vacancy.

Population Growth

Exhibit A shows historical U.S. housing stock (millions of units) divided into three categories alongside the total adult population. Housing stock has closely tracked adult population growth.

There was a massive demographic shift in the 60’s/70’s/80’s as baby boomers aged up and the adult population grew faster than the total population (Exhibit B), and growth in occupied housing stock followed suit. When that demographic driver ran out of steam, growth in the occupied housing stock fell, and it’s difficult to see how there should be any meaningful demographic tailwinds from here. Some unusual things happened during COVID causing a divergence between adult population growth and occupied housing growth, but I’ll get to that later. For now, a good starting point for thinking about growth in the housing stock is a view on total population growth.

Population growth is a function of natural increases (births less deaths) and immigration. Exhibit C shows the component pieces of population growth since 1950 using World Bank data. Natural population growth has been decelerating for decades, but that isn’t unusual. Many developed countries have experienced this deceleration, and many countries in Europe already have negative natural changes in population. I’m no expert but it feels an awful lot like that’s where the U.S. is headed. Obviously 2020/2021 were unusual with an elevated death rate, and maybe natural population growth accelerates modestly in coming years, but the pre-COVID trend is clear.

If natural additions are becoming negligible then the more important driver is net migration, which was only responsible for ~20% of population growth in the 1960’s but more recently drove >50% of total population growth. Since the end of WWII net migration has added an average of 30-40bps to total population growth, but a policy change in the early 90s saw net migration briefly contribute roughly 70bps. Like natural increases, net migration dropped off a cliff in 2020, but appears to be bouncing back recently. Barring a significant change to immigration policy, I think it’s reasonable to assume something like 30-40bps of population growth from net migration for the foreseeable future.

Combined, I think a fair estimate for population growth over the next 5-10 years is 50-60bps/year. This would assume no major change to immigration policy and natural increases somewhere along the pre-COVID trendline. All else equal, demand for total occupied housing would therefore also increase by 50-60 bps/year.

Adults/Household

But all else probably isn’t equal. Ignoring demographic changes, which should be modest, the other factor to consider is adults/household.

In addition to the decennial census, there are three major surveys conducted by the Census Bureau that measure total housing units on a more frequent basis: the American Community Survey (ACS), the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS/ACES), and the Housing Vacancy Survey (HVS). It’s shocking to me, but there are relatively large discrepancies in housing count across these surveys, and none of them ever actually match the decennial census data, which should be pretty accurate. For example, the CPS/ACES estimates were roughly 5.0mn units higher (~4.5%) than the HVS estimates over the last 20 years, and both data sets are often off by more than 1.0mn units relative to the decennial census. The CPS/ACES estimates were also a lot more volatile than the HVS estimates. For those interested, Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) explains why the surveys spit out different estimates and you can find the full paper here. Long story short, the ACS can probably be ignored, the CPS/ACES likely overestimates housing units, and the HVS likely underestimates housing units (the CPS/ACES and HVS estimates diverged in the early 2000’s because the HVS changed their survey methodology).

The reason I’m telling you all this is because the historical adult/household calculations end up being quite different depending on which survey you rely on for household estimates (denominator). In Exhibit D I show adults/household using household estimates from both surveys. I also show the average of both surveys, which tends to be closer to actual census results every decade and is probably a fair approximation between decades if CPS/ASEC consistently overestimates units and HVS consistently underestimates units.

While the magnitude of change isn’t totally clear over the last twenty years, I do think we can confidently observe that adults/household declined considerably from 1965-1990, and that adults/household have most definitely increased since then. It also seems to be true that adults/household tends to increase around recessions, although once again the magnitude is a little unclear.

Adults/household isn’t exactly a driver of occupied housing, but rather a reflection of the true drivers like affordability, family structure, and demographics. For example, a study by the Urban Institute showed that in 1940 something like 90% of households were family units and 76% of households were married couples. By 1980 only 72% of households were family units and 58% were married couples. During this period, the authors indicate that the average age of first marriage increased, there was a decrease in the marriage rate, an increase in the divorce rate, an increase in the propensity of non-married people to live alone (instead of with parents), and an increase in life expectancy (leaving more older adults in single-person households). All these factors led to fewer adults/household and increased demand for occupiable housing stock (you can see from Exhibit B that growth in occupied housing stock outpaced adult population growth as adults/household fell). Real home prices also peaked in the late 70’s and didn’t recover for 9 years, while mortgage rates peaked in 1980 and then fell rapidly through the 80’s – this led to improving affordability and a reduction in adults/household.

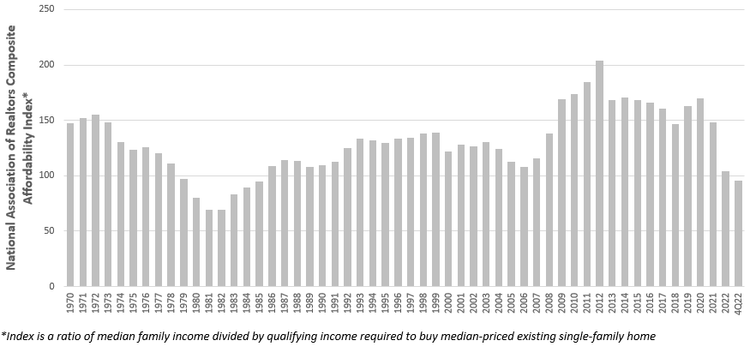

Some of those themes have since reversed course. For example, the divorce rate peaked in the 1980s and has fallen steadily since. Unmarried people are also more likely to live with roommates today and young adults are living with their parents longer. The National Association of Realtors Housing Affordability Index also showed that affordability deteriorated from the mid-to-late 1990s until the GFC. This helps explain why adults/household trended higher during that decade, and then continued climbing through the GFC.

When the 2020 census data was released, the HVS and CPS/ACES surveys revised their housing unit estimates, so the big decline in adults/household based on HVS data in 2020 probably isn’t right (more likely it was overstated prior to this). Nevertheless, all survey data shows that adults/household did decline through COVID. I suspect that it’s some combination of record low rates and unusual migration on the back of remote work through COVID that contributed to this decline.

I generally find it hard to see how adults/household would fall materially from here like it did from the 1960’s to the 1990’s. If anything, I think the recent changes in affordability might drive adults/household higher in the near term. I’d also note that adults/household tends to increase during recessions, and that seems like a very real possibility in the near future (but eh, who knows). Either way, the slightest increase in adults/household for whatever reason actually has very big implications for housing flow. For example, a 0.01 increase in adults/household in a given year would completely offset demand for incremental housing units that would come about from a 50bps increase in the population (holding vacancy constant). The inverse is also true, which helps explain why the housing market remained strong through COVID despite paltry population growth (the decline in adults/household helped support demand, which reconciles the divergence between occupied housing unit growth and adult population growth from Exhibit B). Let’s put a pin in this for now and circle back later.

Vacancy

Population growth and the drivers behind adults/household both impact demand for occupied housing stock. However, the homebuilding industry can’t adjust activity immediately for this changing demand on a unit-for-unit basis, and vacant housing stock helps regulate the ebb and flow of housing demand. When vacancy rates fall, prices go up which destroys some marginal demand and incentivizes marginal supply (and vice versa).

We have historical data from the HVS survey on the component pieces of vacant housing stock, and I’ve shown these component pieces in Exhibit E. Today, something like 10% of all housing units in the country are unoccupied, but that’s less than at any point since the late 1980’s. It’s important to point out that the HVS survey data being used here has historically differed from decennial census data, and from 2001-2019 I think HVS was overstating vacancy rates (understating renter occupied housing units). In 2020, the HVS data was recalibrated based on the new decennial census, which explains the step change in vacancy rate (and confirms that HVS was likely overestimating vacancy prior to that). Despite data that likely has a high margin of error, I still think we can conclude that vacancy today is generally low relative to the last few decades.

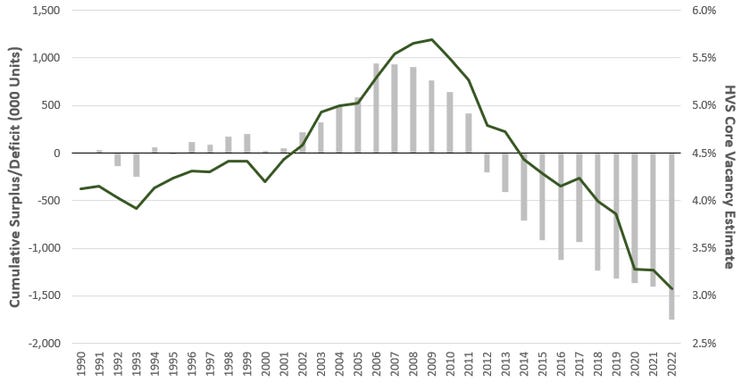

The aggregate data masks what I consider core vacancy declines. I split out vacancy rates into two categories (Exhibit F): core, which includes units for rent, units for sale, and units rented/sold but not yet occupied; and everything else, which includes seasonal, occasional use (vacation homes), URE (usual residence elsewhere), and other (foreclosed, needs repair, currently being renovated, units being prepared for sale, etc.). The graph on the right shows that there has been some modest growth in housing units that aren’t available to meet new household formation (ski lodges, second homes, requiring repair). The graph on the left shows that true vacancy rates (stock I’d consider available to meet new household formation) is basically at a 60 year low. In my view, a big part of the housing bull thesis is predicated on low (and falling) core vacancy rates being symptomatic that homebuilders in the U.S. are underbuilding relative to incremental demand. And that bring us to housing flow.

Housing Flow – Long Term View

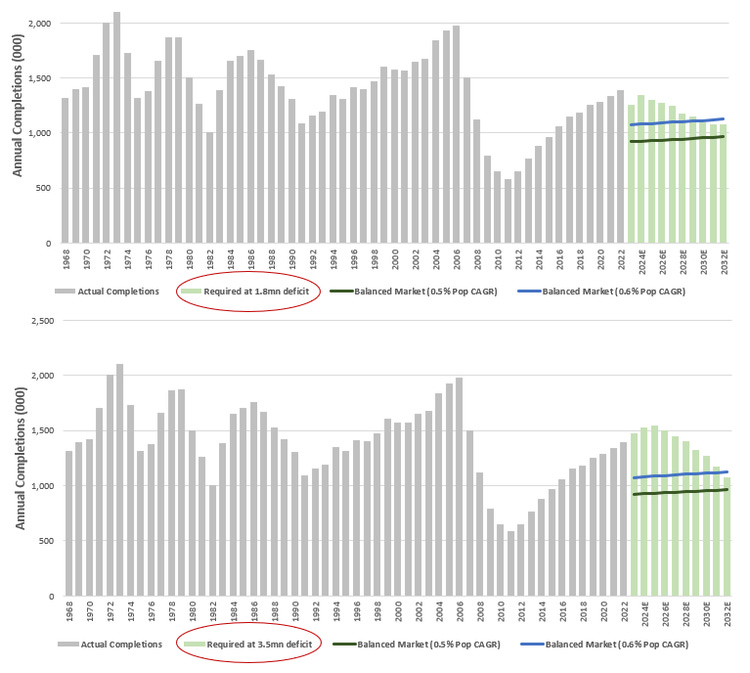

Exhibit G shows total housing completions/year including all single family and multifamily units. It’s wild to see that total completions fell by a whopping 70% from 2006 to 2011 and have only gradually recovered to somewhere around the trailing 60-year average. Again, I think a housing bull would point to this and say that for most of the last ~15 years the industry had been underbuilding, which supports the thesis that downside to completions today is minimal and explains why core vacancy rates have declined since the GFC and are now at multidecade lows.

I think it’s helpful to compare cumulative actual completions with cumulative required completions to assess whether there is a housing deficit, and if so, to what magnitude. The primary driver of required completions is population growth, which drives higher occupied housing units, but there are three additional factors to consider:

Permanent Losses to Housing Stock: The Census Bureau estimates loss rates by vintage which you can find here, and they suggest that average loss rates range from approximately 0.00%/year for homes 0-10 years old to 0.30%/year for homes older than 60 years. The median age of the housing stock has gone up from something like 25 years old in 1990 to 41 years old today, so my rough math suggests that weighted-average loss rates were probably 0.06%/year in 1990 and are probably closer to 0.15%/year today. From 1990-2022 I estimate that the average loss rate was 0.09%/year, which added an average of 100-120k units/year over that period that needed to be replaced.

Growth in Seasonal and Held Off Market Units: there are vacant units included in the housing stock that aren’t available for sale or rent, which the Census Bureau classifies as either Seasonal or Held off Market. Roughly 65-70% of these units are places like ski lodges, vacation homes, time-shares, and housing for migrant workers. The remainder is held off market because of extended absences, foreclosures, repairs/renovations, etc. Cumulatively this category has grown slightly faster than occupied housing units (in particular, occasional use housing) and has added roughly 75k units/year to required completions.

Change in Adults/Household: as I highlighted earlier, adults/household reflects other factors like demographic changes and affordability. Adults/household is slightly higher today than in 1990, but if it had remained unchanged over that period then the industry would have had to build nearly 2.0mn additional units over the last thirty years (holding everything else constant). Based on a variety of affordability metrics (which I’ll expand on later), affordability over the last 5-10 years was much better than prior to the GFC, so I suspect most of the reason for higher adults/household since 1990 is because of factors unrelated to affordability.

I decided to use 1990 as the starting point for calculating the cumulative surplus/deficit in housing that might exist today. I chose 1990 in large part because it seemed that the market was more-or-less in balance between 1990 and 2000; from 1990-2000 core vacancy rates were relatively stable/unchanged, real house prices were stable, and industry unit volume was healthy but not exuberant. I also chose 1990 because data revisions in the 1980’s obscures the analysis.

To calculate the cumulative housing surplus/deficit I deducted required completions from actual completions, where required completions were a function of adult population growth, an estimate of permanently lost housing units, growth in seasonal/held-of-market units, and the change in adults/household. I did need to make some mental leaps (in part to try and normalize for noisy HVS data), so the margin of error is probably high – but if you want to play around with the model you can find it at the top of this piece. In any event, I ran the calculation using household estimates extrapolated from the decennial census data. I’ve shown the outputs of that analysis in Exhibit H. I also plotted the unadjusted HVS core vacancy rate estimate, which should track cumulative surplus/deficit almost perfectly as the dependent variable. One important underlying assumption here is that core vacancy rates in 1990 were reflective of a balanced market – in other words, if the core vacancy rate today was identical to the core vacancy rate in 1990, there would be no deficit or surplus.

This analysis would suggest that there is currently a housing deficit of roughly 1.8mn units. I’ve seen multiple estimates of the housing shortage ranging from 3.0mn to 6.5mn (Fannie Mae estimated a 3.8mn deficit in 2019), so my analysis is clearly less supportive of the housing bull thesis than the consensus. One way that I could get to a 3.0-4.0mn unit deficit range is if I assumed that adults/household should have stayed flat since 1990 (since adults/household went up, demand for housing units fell), and that adults/household going up was indicative that not enough housing was available. I suppose that’s possible, but I’d pushback on this assumption given that affordability was generally very favorable between 2010 and 2021. In any event, I’d loosely put the deficit goalposts at 1.8-3.5mn units.

The next thing I did was back into how many housing units the industry would have to complete to cover those housing deficits inside of a decade assuming adults/household remained unchanged from 2022 levels (2022 happened to be roughly in-line with the T20Y average). In this case, I’m assuming an adult population CAGR of 0.55%. I also included a forecast of required completions at 0.5% and 0.6% adult population growth rates assuming the market was already in balance today. The output of that analysis is shown in Exhibit I. There are two things to take away here. First, if adults/household remained unchanged, the market was already balanced today, and adult population growth ended up being 0.55%/year, then the industry would be overbuilding to the tune of ~30% using 2022 completions! Second, even though the deficit is clearly supportive of activity levels (light green bars are higher than the dark green/blue lines), it’s not big enough to justify any sustained growth in industry completions from 2022 levels. In fact, at a 1.8mn unit deficit completions would have to average just 1,200k units/year (vs 1,392k in 2022) to reach a balanced state. At a 3.5mn unit deficit, completions would have to average 1,375k units/year to reach a balanced state. And once the market is balanced, completions would fall a lot from there. I have no idea what path completions will take, and it’s not even that clear how big the deficit is, but any reasonable deficit estimate would suggest we’re at-or-near peak completion activity today.

Obviously, a lot of assumptions are required to come up with these estimates, and the smallest change in key drivers can have a large impact on required completions. I therefore thought it would be useful to include the data table in Exhibit J that shows F10Y average required completions/year to work off the deficit under various adult population and terminal adult/household scenarios. In order for industry activity to increase much from 2022 you’d have to assume that A) adult population growth over the next decade defies the 30 year trend I highlighted in Exhibit C, and/or B) adults/household declines from here. I wouldn’t be very comfortable underwriting either of those assumptions, but if you’d like to play around with the model you can find it at the top of this piece (there are other assumptions you can flex that also change required completions).

Despite doing all this analysis, I personally hold the view that it’s a fool’s errand to try and forecast industry activity with any real confidence, particularly beyond a year. There are just too many difficult-to-forecast key drivers you need to guess right, and the historical data you’d use to inform a forecast is far from perfectly accurate. But if you put a gun to my head, I’d guess that industry completions will fall over time and run-rate activity levels after the market is balanced are significantly lower than current activity levels. At the same time, I don’t think the industry is at any risk of a GFC-magnitude decline in activity, which brings us to the Short-Term View.

Housing Flow – Short-Term View

Almost all the industry data I’ve seen has been incrementally negative for homebuilder prospects over the next year. The most obvious place to start is affordability.

No affordability discussion is complete without the obligatory reference to mortgage rates and home prices, and I’ve shown both in Exhibit K from 2005 through December 2022. The 30Y fixed mortgage rate doubling inside of a year goes a long way at killing incremental demand – all else equal, that increases monthly mortgage payments by 30-35%. The median selling price of new single-family homes also increased by ~50% from the start of 2020 to October 2022 (the median selling price of existing homes experienced something similar).

What I find most remarkable is not the change in prices and mortgage rates, but rather the rate of change. The year-over-year increase in median new single-family home prices effectively hit a record through COVID relative to any point since the late-1960s. Even on a T3Y basis, the only time new single family home prices had increased this much was in the early 1970s. Similarly, this was the fastest year-over-year increase in 30Y fixed mortgage rates since 1980. In my view, rapid changes like this are bound to have a large negative impact on completion activity.

The National Association of Realtors (NAR) publishes two indices that track affordability as a ratio of median family income over qualifying income, where the latter is primarily a function of A) median selling prices and B) mortgage rates. The higher the number, the more affordable housing is for the median family – at 100, the median family just barely qualifies to buy the median-priced home. The Composite Housing Affordability Index measures affordability for all buyers, and the First-Time Housing Affordability Index measures housing affordability for first-time buyers (duh). I couldn’t get a long time series for first-time buyers but Exhibit L shows the Composite Housing Affordability Index from 1970-4Q22. While affordability had generally been quite strong following the GFC, the index has plummeted faster than at any point in the data set over the last three years (no surprise given the change in prices/rates). As of 4Q22, affordability was worse than at any point outside of the early-1980s when mortgage rates peaked at 18%, and the median family no longer qualifies for the median priced home (index value is <100).

Affordability is even worse for first-time buyers, with the index down from 112 in 2020 to 63 in 4Q22, indicating that many first-time buyers are priced out of the market. First time buyers typically represent 30-40% of all buyers annually (new and existing homes), and we can see that first-time buyer share already dropped in 2022 as affordability plummeted.

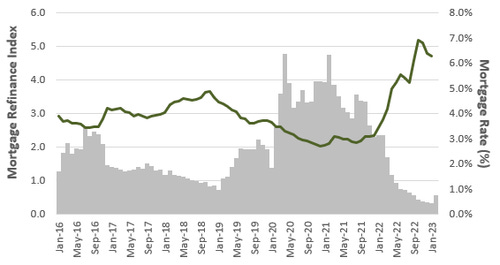

As an aside, the remaining 60-70% of buyers are existing homeowners, and given how many existing homeowners refinanced through COVID, a lot of these buyers are unlikely to move any time soon – indeed, mortgage refinance applications are down 90% from the peak and are ~65% lower then the T4Y pre-COVID average.

In any event, if first-time buyers are increasingly priced out then they’ll have to turn to the rental market. But rental affordability has also deteriorated as rents have rapidly increased alongside housing prices. Exhibit O shows the HUD Rental Affordability Index from 2000 to 3Q22, and not only is the index now sitting below 100 (indicating that the median renter will struggle to afford median rent) but rental affordability is also the worst it’s been in over two decades.

With both buyers and renters facing affordability headwinds that largely materialized in the last 1-2 years, I think it’s likely that we see adults/household start to go up again. Maybe young people live at home longer and more people opt to have roommates. That would significantly hurt demand for new industry completions in the near term, even with a housing deficit. In fact, we’re starting to see that play out in important monthly metrics.

Exhibit P shows housing starts vs housing completions for all units and the single-family subcomponent (these are seasonally adjusted annualized data points). Completions have yet to roll over for either category, but housing starts have dropped a lot since early-2022, and housing starts are obviously a leading indicator for completions. I’d also note that the single-family market has rolled over faster than multifamily, and single-family starts in January 2023 were 15-20% lower than average completions in 4Q22. Finally, permits are a leading indicator for starts, and permits are falling faster than starts in the single-family market. In fact, data from February shows that single-family permits haven’t been this low since 2016.

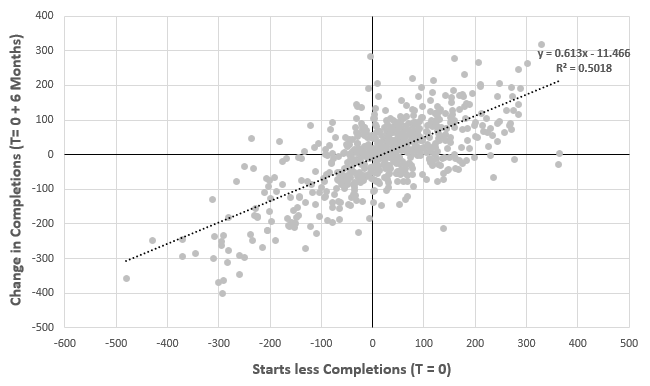

It looks like there is probably something like a 6-month lag between starts and completions and Exhibit Q shows the historical monthly relationship between the delta of starts to completions and the actual change in completions 6 months later going back to 1968 (this is specifically for single-family homes). Based on this analysis, it looks like 2Q23 industry single-family completions could probably fall by 10-15% from 4Q22. Given that permits are down a lot more than starts, I’d expect that completions in 2H23 will be down by more than 10-15% from 4Q22.

The other concerning factor is that the number of units currently under construction but not yet completed is at a record high (literally higher than at any other point in the data set going back to the 1960’s). That’s an awful lot of supply that is going to hit the market in 2023 (likely in the next couple quarters). If buyer/rental affordability remains challenged, I can’t see how this doesn’t lead to higher vacancy and lower prices/rents. Multifamily units are the major culprit here, and single-family homes under-construction-but-not-yet-completed have already rolled over. At the margin, I suppose you could argue that potential downside to ASPs in the immediate future is more pronounced in the multifamily market than the single-family market. However, if affordability remains challenged and multifamily prices/rents fall more than single-family prices/rents, it’s possible that single-family loses unit share (buyers consume less square footage), which would be consistent with what happened during the GFC.

At the company level, I’m also seeing some worrisome data, notably a meaningful increase in cancellation rates. Exhibit S shows cancellation rates going back to 2004 for eight of the largest homebuilders who have consistently reported this data ($DHI, $LEN, $PHM, $NVR, $TMHC, $KBH, $MDC, and $MTH). As of 4Q22, average cancellation rates were approaching GFC levels, and two of these builders reported record high cancellation rates. These are home orders that buyers are walking away from, likely because of the change in interest rates. It’s possible that many of these homebuilders end up accumulating finished home inventory on their balance sheet, and to move that inventory they might have to accept lower prices (either directly, or through incentives). Commentary from most of these builders indicates that they expect cancellation rates to remain high in the first half of 2023, and I’d expect this to result in much lower revenue/margins.

So, what are the outs? Obviously if rates fall, that improves affordability and probably helps stave off any significant decline in activity. You could argue that if wage growth is higher than rent/price growth that affordability would improve, but that takes a long time. So, if wage growth isn’t a near-term solution and rates don’t fall, then the only real near-term fix is a decline in rents/prices. The wall of units under-construction-but-not-yet-completed will probably help with that (supply side). At the same time, if adults/household increases then you get some demand-side destruction. I’m of the view that it’ll be some combination of demand destruction and new supply that leads to lower prices/rents and helps alleviate affordability headwinds. But with vacancy rates already at-or-around multi-decade lows and an already large housing deficit, I think the downside to completions in the near term is probably nowhere near the -70% decline we saw during the GFC.

I was curious to see what consensus expected for revenue from the top 9 largest public builders that collectively had ~25% market share in the single-family market last year, so I pulled historical and forecast revenue for that peer group (Exhibit T). It looks like consensus has cumulative revenue falling by nearly 20% from 2022-2024. That would be something like a 10% decline in ASPs and a 10% decline in unit volume. I suppose you could argue that some of these large builders could take share through a recession, so probably hold up better than the industry, but I can’t help feeling that risk is seriously skewed to the downside for these estimates given everything I’ve outlined so far. That’s especially true considering consensus has 2023/2024 revenue that’s still 30% higher than pre-COVID and the macro landscape is much worse today than it was in 2019 – not to mention cancellation rates have skyrocketed. The other interesting thing I observed is that cumulative net income estimates for 2023/2024 were also 50-60% higher than pre-COVID. I’ll touch on this more later, but margins tend to compress significantly when unit volume and prices fall – cumulative net margin estimates for 2023/2024 are ~10.2% vs 8.6% in 2019. Obviously, some margin compression is baked in already, but if top line ends up coming in lower than consensus, then net income/EPS estimates could miss to a much greater degree.

If it’s not abundantly clear already, I lean more negative than positive on both the long-term and short-term outlook for homebuilding activity and prices, despite the likely housing deficit. I don’t have a strong view as to what most individual homebuilder stocks are pricing in, but the aggregate revenue and net income estimates seem optimistic, so I’d guess that it would be difficult to find attractive risk/reward in this space today.

Single-family construction

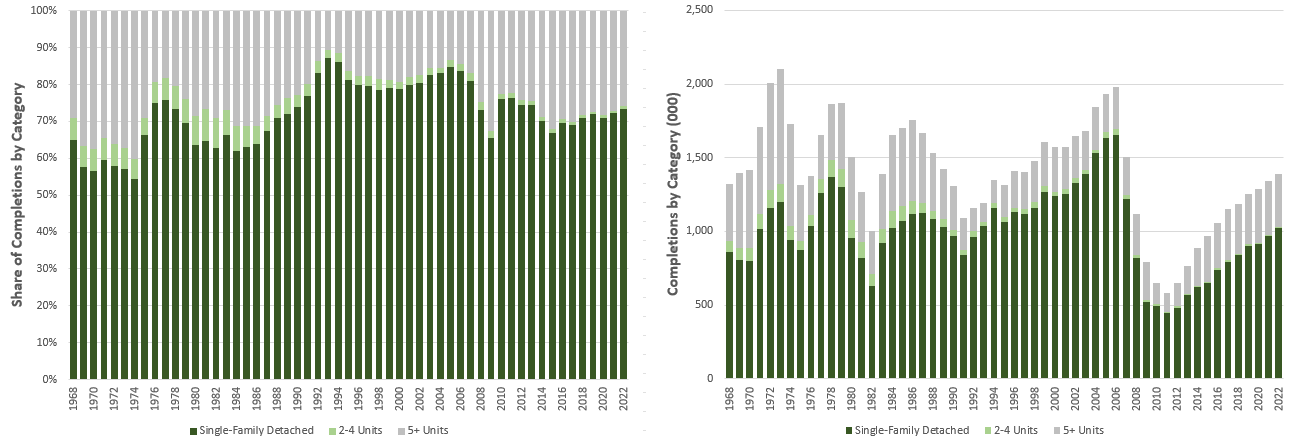

So far, I’ve largely focused on total completion activity, but I’m most interested in single-family (SF) construction because that’s the specific business that NVR and DFH are in. Exhibit U breaks down historical completions by dwelling type (SF detached, 2–4-unit structures, and structures with 5+ units). SF detached homes clearly drive the bulk of total completions, and while that structure type lost modest share following the GFC, they’ve represented a consistent ~70% share of new housing units since.

I do find it interesting that ~65% of total occupied housing units in the U.S. are SF homes, whereas the average across the EU is more like 40%. I get that population density is lower in the U.S. than Europe, which is supportive of more standalone housing, but even in Canada SF homes represent closer to 50% of occupied housing units. Maybe that’s just part of the American dream. I’m not really sure how that mix shift will change in the U.S. over time as population density increases or if affordability headwinds persist, but even if SF homes lost share, I think it would do so at a glacial pace (perhaps with some noise during recessions). Again, this seems like a difficult thing to forecast, but it also feels safe to assume something like 65-70% of all new housing units completed over the next decade will continue to be SF homes.

The Single-Family Competitive Landscape

I think I’ve laid out a reasonable framework for thinking about SF industry completions, but now let’s look at how that pie gets divided and how the competitive landscape has changed over time.

Data from the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) shows that they have more than 20k single-family homebuilder members. The latest data I have is for 2020, but in that year, members completed an average of 26.3 homes per year while the median was closer to 5.0. This is obviously an extremely fragmented industry, where most builders complete just a handful of homes per year and a few large builders drag up the average.

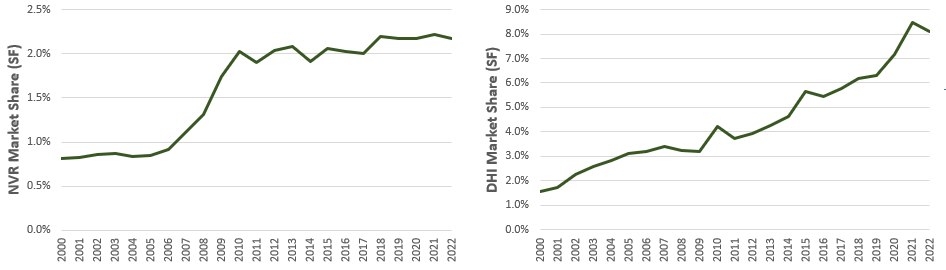

I also pulled data on the 19 largest public homebuilders from 2000-2021 and compared that to industry SF completions to measure change in market share over time (Exhibit W). So, while there are 20k+ builders competing in this market, 19 builders are now responsible for roughly a third of total completions. In addition, those large builders have captured significant share over the last twenty years. These large builders have cumulatively spent many billions of dollars on M&A to consolidate smaller competitors, but by my math most of this increase in share was driven by organic growth outpacing growth from small builders (the NAHB member data showed that plenty of small builders likely went out of business during the GFC, which likely left some share to get picked up by large incumbents).

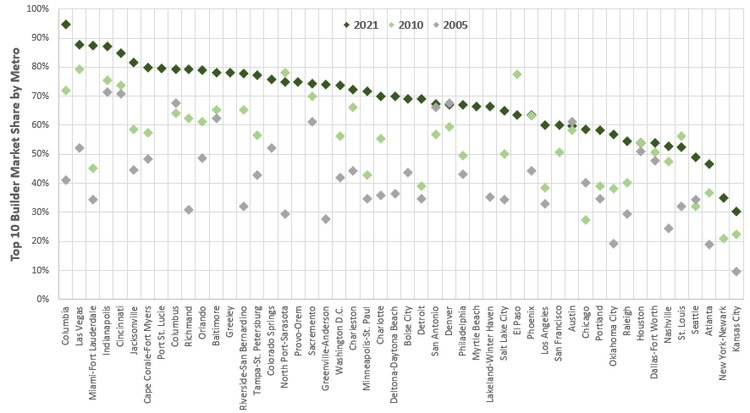

What I also find interesting is that the homebuilding industry appears way more concentrated at a regional level than at the national level, and most metros have become considerably more concentrated over time. Exhibit X shows market share per metro for the top 10 builders in a given region, and how the top 10 market share has changed over the last 15 years. In Miami/Fort Lauderdale the top 10 builders had ~35% share in 2005 but a whopping 87% share in 2021! You can find the data here if you’re interested in clicking through to find share by builder, but diving into each metro I found that the dominant local builder frequently had 15%+ market share. For example, NVR had 25% share in the Washington D.C. area in 2021, despite just 2-2.5% share on a national level. Similarly, NVR had 32% share in Pittsburgh. In Houston, D.R. Horton had 16% share vs just 8% nationally. Lennar had 16% share in Las Vegas and 34% share in Miami/Fort Lauderdale vs just 6% nationally. In Sacramento, Pulte had 18% share vs just 3% nationally. I also stumbled across plenty of private homebuilders that were among the top 10 builders in one metro but didn’t show up in other metros, which tells me that there are plenty of large local builders that only operate in 1-2 metros.

My working theory is that homebuilders benefit from regional economies of scale, and that they’ve leveraged that favorable cost structure to take share from the long tail of small competitors. Rarely do the largest builders appear to take share from each other. Exhibit Y uses Jacksonville, FL as an example, and shows the Top 10 market share over time by builder. Each of the biggest builders have either maintained or taken market share from the rest of the market (not each other), although there is some volatility from year to year.

I’m generally of the view that it would be difficult for a large builder to organically enter a new metro and successfully take share from the largest local incumbents. This is largely a commoditized business, and I’m of the view that it’s difficult for homebuilders to sustainably differentiate themselves to home buyers or developers in such a way that it’s easy to take share. Some of the data I’ve seen also suggests that builder margins can be horrendously low when they enter a new market and haven’t scaled up (I’ll touch on scale economies in Part 2 and Part 3), which can take many years to do. A new entrant must secure lot inventory, and most builders maintain a 5–6-year backlog of lots. Incumbents have probably secured some of the best lots that are most likely to be developed in the next 5 years, and that creates a scarcity barrier to scaling immediately. The poor initial economics combined with the long investment cycle is a big deterrent to entering new metros that are already saturated. That’s not to say it’s impossible, but rather it’s just challenging to do well.

Even though the largest builders only have a 30-35% market share nationally, the metro-level data suggests that regional concentration might start to be an inhibitor to organic growth for the public homebuilders. If it’s challenging for builders to organically enter new markets, and many existing markets are becoming saturated, then the only way to grow units meaningfully faster than the industry is through M&A or by sacrificing profitability. There is probably some runway left to take share from small competitors in markets that the large homebuilders are already active in, but I still think this will be a growing challenge that didn’t exist 10 or 15 years ago.

Unit Economics and Historical Industry Performance

In my view, referring to public companies in this space as “homebuilders” is a misnomer; one that I’ll use, but nevertheless inaccurate. Most public homebuilders don’t physically build homes – they subcontract that part out. Instead, these companies are in the business of identifying and securing lots, designing homes, finding buyers that will commit to purchasing finished homes, coordinating the construction process, and providing the net working capital (NWC) required to fund the period between securing lots and the home closing date. As a result, these businesses have almost no PP&E, spend almost nothing on capex, and have few employees on payroll relative to what’s required to build homes. Most of the capital deployed is NWC, where that NWC is the cost of securing lot inventory, finished homes, and construction-in-progress, less customer deposits for homes and other AR/AP adjustments. There are some important things to flush out on the capital deployed front, but I’ll circle back on this at the end and in Part 2.

Ignoring capital deployed, the unit economics are simple for this industry. In Exhibit Z I’ve illustrated roughly what unit economics looked like for the homebuilders in the five years prior to COVID. Gross margins tended to be somewhere around 18-19%, where COGS consisted of land (roughly 20% of COGS), material (40%), labor (35%) and commissions/other (5%). This ignores capitalized interest, so represents an unlevered cost of goods sold. SG&A per unit was roughly 8-9% of the average selling price (ASP), which gets us to a ~10% unlevered operating margin.

The vast majority of COGS are variable costs like commissions, labor, and materials, while some portion of SG&A is also variable. Large homebuilders get some scale economies on things like material and labor, but I like to think of these as largely flow-through cost items – if the cost of labor goes up, it impacts all builders and ASPs across the industry follow suit. I also think it’s true (and fairly obvious) that these are commoditized input costs, where no large builder would have a materially advantaged or disadvantaged cost structure relative to any other comparably large builder (although a large builder would have scale advantages over a small builder). The same goes for ASPs, which tells me that builder margins and returns should reflect that of a commoditized industry if it’s largely scaled regional players competing against one another. In this commoditized industry, there are only two cost items that explain most of the variability in unlevered margins through a cycle: land and SG&A.

As I mentioned previously, most builders are sitting on 5-6 years of lot backlog. They can either acquire those lots outright and hold that inventory on their balance sheet, or they can purchase lot option contracts. More on this later, but the most common strategy is to hold lot inventory on the balance sheet. In that case, Builder ABC acquires a lot for $65k at t=0 (it’s not quite that simple, but good enough for this example). At the time of acquisition, let’s say they expect the ASP from the home sold on that lot in five years to be $400k, which helped inform the bidding price for the lot. But let’s say house prices fall by 20% by the time a home is sold on that lot. If that happens (for example, the median selling price on new SF homes fell 22% between March 2007 and March 2009), then the cost of the land/lot went from 16% of the expected ASP to 20% of the realized ASP. All else equal, that would compress margins by 4% for a business that only had run-rate margins of 10% to begin with. The same dynamic works in reverse if house prices end up being higher than expected.

A similar dynamic is at play with SG&A, which is mostly labor and has some fixed cost components. All else equal, if ASPs fall then SG&A as a % of revenue goes up. Similarly, because of the fixed cost dynamic, if unit volume falls then SG&A/unit goes up. In recessions, unit volume and ASPs tend to both fall, which compounds negative operating leverage. The opposite is also true in a hot housing market. The first graph in Exhibit AA shows SG&A as a % of revenue for 10 builders that have been in business since 1998, and we can see that SG&A as a % of revenue almost doubled through the GFC as both unit volume and ASPs fell. The second graph in Exhibit AA shows SG&A metrics for DHI specifically, and we can see that SG&A/unit in absolute terms went up after the housing market rolled over in 2006 and took a few years to right-size – this contributed to significant margin compression.

The final factor to consider is leverage. Many builders borrow to fund part of their NWC investments in land/lots/inventory, and that interest cost is often capitalized and included in COGS (even if it wasn’t, this would just compress net margins). If inventory turnover falls in a slow housing market, that cumulative carrying cost increases which reduces profitability. I’ll touch on leverage again later, but this burned a lot of builders during the GFC.

Exhibit AB takes data from the same 10 builders since 1998 and shows how operating margins correlate with change in ASP and change in unit volume. A multilinear regression of a change in ASP and change in unit volume against operating margins had an r-squared of 70%, so these variable seem to have pretty strong predictive power. When times are good, they are really good, but when times are bad, they are really bad.

We know that margins are very volatile through the cycle, but I was also interested in seeing if there had been any structural changes in profitability over time. Exhibit AC shows historical ROIC and operating margins across the comp set. Despite meaningful consolidation over the last twenty years, the industry hardly seems more profitable in the years prior to COVID than the early 2000’s.

I’ve only been able to draw two conclusions from Exhibit AC. Either A) this business is so commoditized, and the barriers to entry are so low, that we shouldn’t ever expect to see a meaningful sustained improvement in profitability despite consolidation, and/or B) these large builders have sacrificed margins/ROIC to take share/grow. It’s most likely a little of both. Either way, the economics have historically been pretty ‘meh’, which is exactly what I’d expect of a commoditized industry.

But sweet mother of God margins and ROIC went gangbusters through COVID. In many cases, 2022 was on par with, if not the best year for builders for as long as I have the data. From 2019 to 2022, unit volume for this comp group increased by roughly 30% and ASPs were up anywhere from 17-32%. Given what I’ve explained above, I’d expect to see margin expansion any time that both unit volumes and ASPs increase quickly. That’s exactly what happened. Operating margins were 2x higher in 2022 than 2019, with ROIC following suit. I think it’s pretty obvious that 2022 margins/ROIC aren’t sustainable, and the latest quarterly data and guidance figures show that margins are starting to compress. Most sell-side estimates have revenue and margins both compressing through 2023 and 2024, so I suspect that it’s well understood that builders were overearning through COVID. Even still, margin estimates (and therefore EPS) look optimistic relative to pre-COVID as I already outlined in Exhibit T. If industry activity or ASPs fall by more than 10% over the next two years, I suspect there would be significant downward revisions to estimates, and that doesn’t appear to be priced in from the 10,000-foot view.

Balance sheets

One big change amongst the public homebuilders since the GFC is their use of leverage. There are a lot of different ways to assess leverage, but in Exhibit AD I slice and dice it on multiple metrics for 10 of the largest comps (DHI, LEN, PHM, TOL, NVR, TMHC, KBH, MDC, MTH, CCS). For each metric I’m taking aggregate net debt over the aggregate denominator. On every metric, leverage is lower today than when housing activity peaked in 2005. In fact, aggregate net debt at the end of 2022 of $11.7bn was less than aggregate net debt in 2005 of $13.5bn, and yet these businesses completed 23% more units last year than 2005. Even if we used 2022 net debt vs 2019 denominators (a more normalized number), the industry would have comparable or better metrics than 2005 on all four measures.

Seven of the ten builders saw absolute net debt dollars decline through COVID, often because of actual debt reductions (not just growing cash balances). Against that backdrop it looks like the big competitors in this industry have taken the last two years as an opportunity to de-risk, which is a positive lesson learned from the GFC when leverage contributed to significant negative net income (even in instances where operating income was slightly positive). Whatever happens to industry activity over the next two years, I think these businesses are much better positioned to weather the potential storm than at any other point in the last two decades.

Lot Acquisition Strategies and Invested Capital

As I’ve already alluded to, most of the capital deployed in this business is NWC (PP&E is negligible). The bulk of that NWC is a combination of finished homes, construction-in-progress homes, and land/lot inventory. Some of the better managed builders tend to avoid building too many homes on spec, so typically carry small balances of finished homes that aren’t yet sold, and construction-in-progress inventory turns over pretty quickly. The real differentiation between builders is therefore how they procure their land/lot backlog, which frequently represents >50% of total NWC.

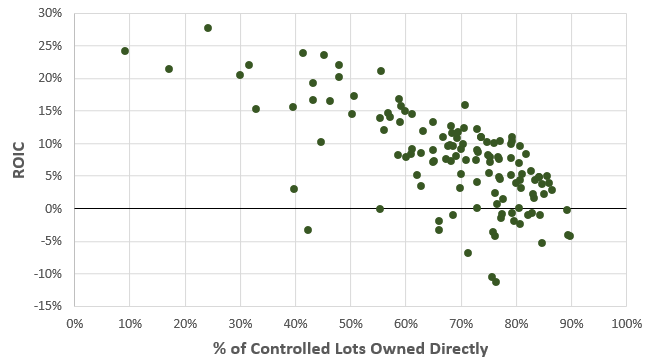

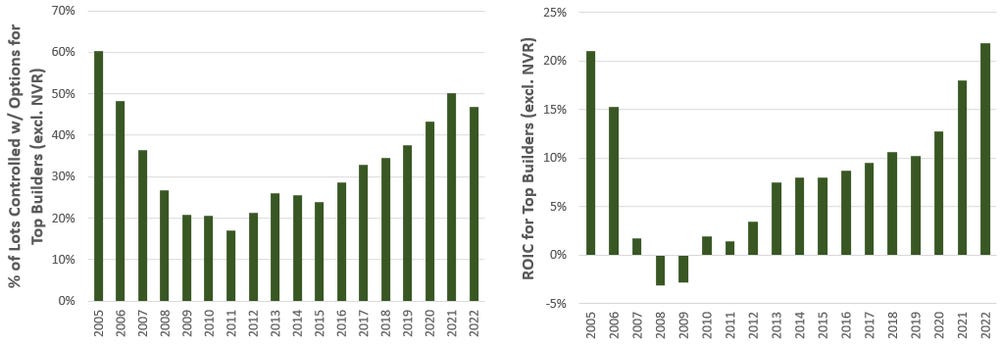

Through a cycle, it looks like the average builder has a 5-6-year backlog of lots, which are called controlled lots. I’ve simplified this a little, but there are basically two ways to control a lot. The first is to purchase that lot (or the land where the lot will be) and carry that investment on balance sheet. The second path is to purchase lot option contracts, where the builder pays a fee equivalent to 10-15% of lot value. The builder can exercise that option down the road to acquire the lot, but they lose the fee if they elect to let the option expire. Clearly, the most capital efficient path is to control lots via option contracts. If most options get exercised (which does seem to be the case outside of recessions), then the lot option strategy would lead to higher ROIC. Even in recessions where the option fee is more likely to get forfeit, builders pursuing this strategy aren’t at risk of writing down owned lot inventory or tying up capital on owned lots that aren’t turning over. It therefore looks like the lot option strategy should yield better returns on capital through any point in the cycle.

In Exhibit AE I plotted ROIC vs the percentage of controlled lots that are owned outright for the top 10 builders (excluding NVR) from 2005-2021. As expected, the graph shows a strong inverse correlation between ROIC and the percentage of controlled lots that are owned outright.

I took the same peer group and calculated the average percentage of lots that were controlled via options from 2005-2022, and then plotted average ROIC for the same period (Exhibit AF). ROIC obviously ebbs and flows with margin compression/expansion, but once again it’s clear that ROIC benefits when builders deploy fewer dollars to control lots.

For additional context, NVR is the poster child of the lot option strategy (nearly 100% of their controlled lots are owned via option contracts), and they deploy $10-13k of NWC per controlled lot vs the average top 10 builder of closer to $60k. In the 3 years prior to COVID NVR generated a ROIC of ~60% vs the average top 10 builder of closer to 12%. During the GFC when most builders generated a negative ROIC, NVR’s ROIC never fell below 30%.

The obvious follow up question here is why doesn’t every builder just exclusively utilize lot option contracts like NVR? I read through several Tegus transcripts with experts from NVR and their competitors, and these comments help explain why the option acquisition strategy isn’t dominant:

NVR has “looked into other markets as they occasionally do. They often show up and go around and talk to developers – we know because the developers then turn around and tell us what they heard. And the developers are really not interested in the model they present [lot option contracts] because the developers don’t want all the risk. That’s not why they got into it. They want to share the risk and develop mutually beneficial relationships. So you see slow expansion [by NVR] into secondary markets”

“NVR has a deep capital bench, and they can fund large projects, but they also have very specific requirements, particularly of developers. And so I end up talking with developers who just don’t want to work with Ryan [a division of NVR] anymore. Maybe the money is good, maybe the money is steady, but they are so specific and so demanding and push the risk off on the developer to a point that some developers just want to shop around… and maybe the dollars won’t be as high, but if the flexibility and the stronger relationship is there, maybe that’s a better direction to go in. I’m sure there are some developers who are thrilled with it and happy… but at least one of the guys I talk to is just tired of it and looking for some alternatives”

“…these agreements are called takedowns. So [NVR] agrees with the developer that we are going to sell X amount of homes per quarter. And then as long as they hit that goal, then they have good relationships with the developer, and that’s how they continue to do business. That’s why they put so much emphasis on hitting their business plan. These presales, these grand openings, these VIP events, they’re critical”

“So they [NVR] do a lot of homework. And a lot of builders don’t do that. NVR spends a lot of time really doing their research before they even go into purchasing a land deal. The amount of work that goes into it is sometimes a year or two years in the works before it even gets to fruition. And a lot of people don’t understand that, but some builders will just go, they’ll buy something and they’re like, okay, let’s figure it out. But NVR does a lot of research before they even invest”

“NVR has to go partner with everybody to get their land. And it makes sellers perhaps nervous about what they’re getting into with them. But then they deliver, and they will deliver on pace. And it’s largely because their sales training is phenomenal, and their production training is phenomenal. And so they will sell out these communities, they’ll do it well and they’ll deliver good houses to spec and on time”

NVR specifically targets entry-level, simple, and cheap homes. They do this because they can pump them out quickly to a large potential customer base where affordability is a key consideration: “it was always, the standard is the standard. A lot of, not all, but a lot of builders, you go in and they’ll have a design studio, where you have to go to after the fact when you pick out your countertops, your cabinets, your lighting, that kind of stuff. With NVR, they don’t have a design studio. I would say, probably 98% of their communities are their color pallets. So when you walk into their offices, on the walls, they have a display of like maybe anywhere from four to six different interior color packages. And the customer picks one of those six packages. Anything on that package is not interchangeable. You can’t say, I want to switch this for that. You can’t do that. It’s like, no, you pick either one, two, three, four, five or six, and there’s a price point for each of those”.

As I read through these comments and others like them, it strikes me that most landowners/developers hate dealing with builders who require option contracts and push the risk off to the landowner/developer. I think NVR succeeds at doing this because they have a reputation of executing on most of their option contracts on a very rigid expiry schedule (developer risk is minimized), and because they can take down so many lots at a time (scale). If a landowner/developer has worked with NVR for years, generally gets paid above-market, generally gets most options exercised, and can sell entire communities to a single buyer, I can see how their strategy can be sustainable. NVR is able to consistently exercise options because A) they do so much deep research on new communities before committing (they know demand will be there), B) they can takedown an entire community, and C) they emphasize simplicity/affordability over customization, which means it’s easier to stick to a pre-defined takedown schedule. I loosely hold the view that builders who don’t have rigid controls/processes, or builders that sell customized/higher-ASP homes, don’t have a model that lends itself well to option contracts and the attached takedown schedules.

I also think it’s true that the lot option strategy is harder to scale. NVR has been in business for more than 40 years and is only in 14 states – they’ve relied almost exclusively on option contracts to control lots. DHI started 2 years before NVR and is in 29 states – until recently, they owned most of their controlled lots outright. Exhibit AG shows SF market share for each business from 2000-2022, and outside of the GFC NVR hasn’t seen any notable share gains while DHI has consistently taken share (some M&A was completed here, but most of this is organic growth). My working hypothesis is that DHI has had an easier time entering new markets because they’re willing to just purchase land/lots outright, which developers obviously prefer. So, it appears that there is a trade off being made between ROIC and reinvestment rates. There is merit to both strategies, but at the margin I personally prefer what NVR is doing (lower reinvestment rate, but higher returns and lower risk). I also find it interesting that DHI acquired a residential lot development company called Forestar in 2018 and now owns just 23% of their controlled lots – this was a clear effort to “enhance operational and capital efficiency and returns” and is another data point to validate the attractiveness of the lot option strategy.

Finally, I had come across a few arguments that compensation programs at some homebuilders created perverse incentives like unit growth over ROIC. I did find a few instances where that used to be the case. For example, LEN (2nd largest builder) paid long-term incentive bonuses based on home deliveries and revenue growth up until 2017, but then shifted to relative gross profit, relative return on capital, and relative TSR in 2018. For the decade leading up to 2018 LEN outright owned 75-85% of their controlled lots, but since that new incentive program was put in place owned lots as a percentage of controlled lots has dropped to sub-40% (Exhibit AH). This reminds me of the O&G industry, which has been belabored for having perverse incentives and has just recently started thinking about ROIC. I think a compelling argument can be made that more builders are emphasizing ROIC over topline growth, and that could actually lead to structurally improved ROIC for this industry. Even still, there is a lot of variances in option acquisition strategies across the homebuilding universe, and I think this will continue to be a large differentiator in the future.

Summary

Despite a sizeable housing deficit that likely exists today, I think industry completions are at-or-near peak levels. Barring an immediate reduction in mortgage rates (which I don’t think is likely), affordability headwinds are likely to result in fewer completions and lower ASPs for this industry in 2023/2024. Beyond that, I think there is some support for new housing, but run-rate completions are probably 25% lower than 2022 if natural population growth continues to decline and net migration doesn’t change materially. Once the deficit gets worked off, this industry probably produces fewer run-rate units than it has been over the last few years.

While I haven’t done detailed work on every builder in this industry, aggregate consensus estimates appear high to me, and I generally feel that expectations implied by current prices are too optimistic. At the same time, many builders have much better balance sheets, greater regional scale, and more aligned incentives than prior to the GFC. It’s also clear that many large builders have very effectively taken share over time, and I think there is probably room for further consolidation. Against that backdrop, some of the businesses with healthier balance sheets are likely well positioned to act countercyclically in the event of a recession.

As always, I encourage you to reach out if you disagree with anything in this piece or have any questions. You can reach me at the10thmanbb@gmail.com, in the comments below, or on Twitter.

You're a hidden gem my man! Informative read!

This was an amazing piece to read!