Dwight Schar was a teacher by trade. He quit his teaching job after one semester in the 1970’s to pursue a career in homebuilding with Ryan Homes – one of the largest home builders in the country at that time. He left Ryan Homes and started his own homebuilding business in 1980 called NVHomes, where he expanded aggressively in the Washington, DC area. In an ironic twist of fate, NVHomes acquired Ryan Homes in 1986. This was especially remarkable considering the latter had generated 5x more revenue than NVHomes the previous year. This was a “case of the pygmy eating the whale”. The new entity was renamed NVR (NVR 0.00%↑) .

Even before acquiring Ryan Homes, Schar had expanded aggressively and NVHomes exceeded $100mn in revenue just 5 years after opening its doors. A big part of that growth was funded with leverage, where Schar borrowed a ton of money to “buy vast swaths of land and hold it” for use in future homebuilding. The Ryan Homes deal was also a leveraged buyout. In the early 1990’s “interest rates rose sharply into double digits, home sales dropped precipitously, and Schar was left with loans on land he suddenly did not need”. Industry-wide completions fell by more than 50%. It was a perfect storm for NVR, which levered up significantly just years before the cycle turned, and they filed for bankruptcy in 1992. Looking back on the experience, one of Schar’s close developer friends noted that “Schar discovered the hard way that you don’t want to hold a whole lot of land” in this business.

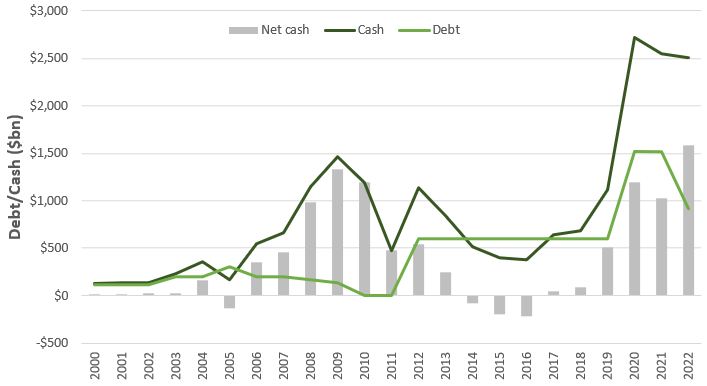

NVR emerged from bankruptcy in 1993 and was once again a public company. Dwight Schar was still at the helm and appears to have taken a solemn oath to never again use leverage, never again own land or empty lots on NVR’s balance sheet, and never again blow the lid on large M&A. Technically, NVR did emerge from bankruptcy with ~3.0x ND/EBITDA but paid off all that debt by 2000 and hasn’t carried any material net debt since. NVR also procures nearly 100% of their backlog via finished lot option contracts as opposed to owning land/lots on their balance sheet. And, since 1993, they’ve deployed <1% of their CFO on M&A. Schar’s new approach has not only led to an outstanding ROIC over the last three decades (orders of magnitude better than other public builders), but also carries significantly less risk of permanent capital impairment than competitors. This combination of extreme risk aversion and capital discipline seems to be what attracted Norbert Lou to NVR in the late-90’s.

Schar stepped down as CEO in 2005, but was the Chairman of the Board until he retired last year. In the three decades managing and overseeing the post-bankruptcy NVR, his strategy hasn’t changed. He found a winning formula and stuck with it. Today, NVR is the 4th largest homebuilder in the country. They build more than 20k homes/year across fourteen states up and down the east coast (New York down to Florida).

NVR has three trade names that focus on different parts of the market: Ryan Homes, which primarily targets first-time and first-time move-up buyers (I estimate 90%+ of total revenue); and, NVHomes and Heartland Homes which both target luxury buyers, but only operate in 4 cities (Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh). In addition to the homebuilding business NVR has a mortgage banking subsidiary called NVRM which sells title insurance and originates mortgages to be sold in the secondary market. NVRM only serves NVR customers and has contributed anywhere from 5-12% of operating income over the last decade. Finally, NVR occasionally enters into JV agreements to develop land/lots, but these investments and the subsequent income have always been a rounding error in NVR financials.

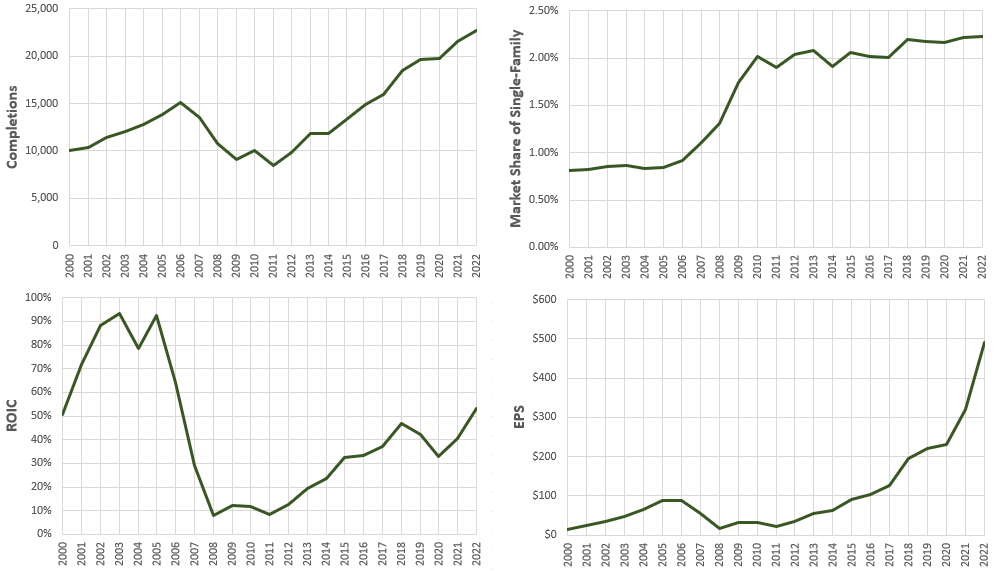

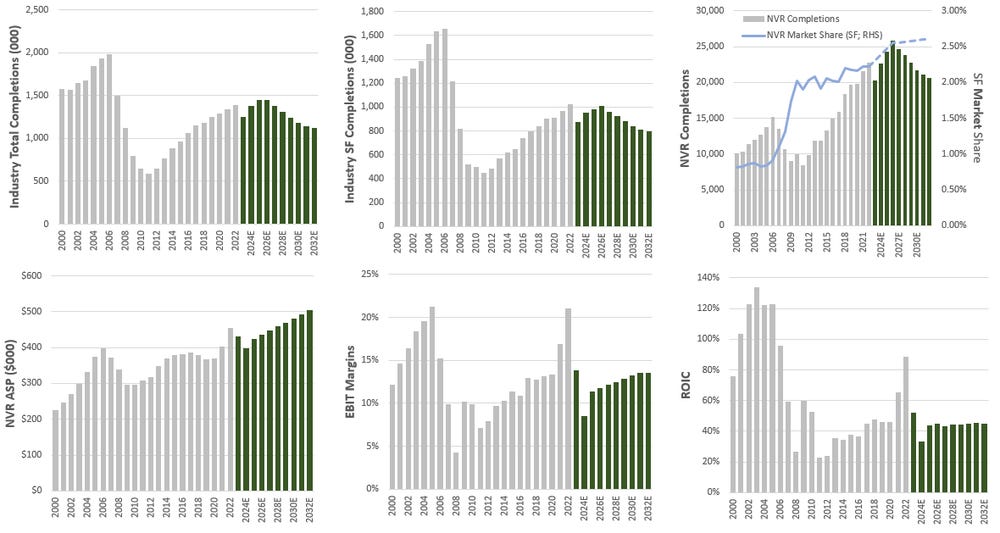

Exhibit A summarizes historical completions, market share, and financial performance for NVR.

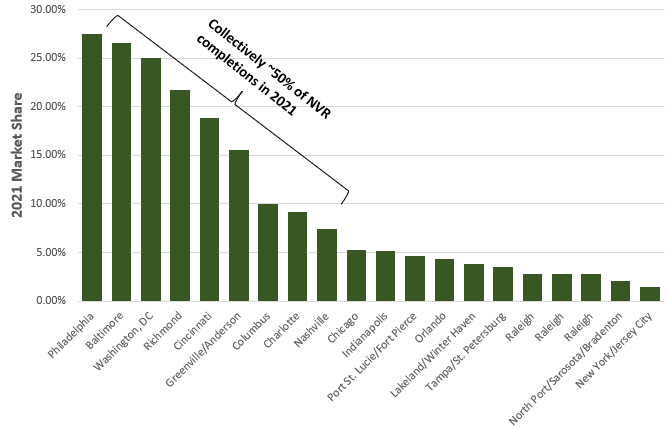

Even though NVR has sub-2.5% market share nationally, they dominate in a handful of metros. Exhibit B shows NVR’s 2021 market share (according to the Builder Online Local Leaders list) across 20 metros where NVR shows up in the rankings. The top 9 metros collectively represented roughly 50% of NVR’s total completions in 2021, while Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, DC represented nearly 30% of total completions. That’s a significant concentration of activity in just a ~200-mile corridor.

NVR only reports revenue per metro where that metro contributes 10% or higher share of total homebuilding revenue, and historically that’s only been the case in Washington, DC and Baltimore. Exhibit C shows the contribution to homebuilding revenue from these two neighbouring metros since 2000. In 2000, these metros contributed a whopping 60% of total homebuilding revenue, but that’s fallen steadily to just 28% in 2022. Funny enough, NVR’s market share in both metros has actually increased considerably over time (for example, Washington, DC was just 8.2% in 2004 and sat at 25.0% in 2021, and Baltimore was at 16.4% in 2004 but 26.6% in 2021). So, the real reason for the steadily declining concentration is that NVR has successfully expanded in other markets, notably Philadelphia, Richmond, Cincinnati, Charlotte, Nashville, Greenville, Chicago, and multiple cities in Florida. In most cases NVR had some small presence in those markets 15-20 years ago and has just taken share. For example, in Philadelphia they went from 6.4% share in 2004 to 27.5% in 2021, in Nashville they went from roughly 2% share in the early-2000’s to 7.4% in 2021, and in Chicago they went from sub-1% share to 5.3% in 2021.

NVR’s growth strategy over the last twenty years has been focused on achieving leading share in existing and adjacent markets. In 2001 they operated in 18 metros and 11 states. More than 20 years later, they operate in 34 metros and 14 states. They entered 3 states (Florida, Indiana, and Illinois) and 9 metros during the GFC, but have otherwise rarely expanded their geographic footprint outside of recessions. Most of the new metros they entered were in states that they already had a presence back in 2001, and in most cases these metros were <100 miles from an existing metro, and where they could likely leverage existing relationships and infrastructure. As I understand it, scale economies are mostly relevant at a regional (not national) level, so this approach of having a dominant presence in a few metros vs a modest presence in lots of metros likely leads to better operating margins, higher ROIC, and wider moats. I’ll expand on this more later, but I think this is an important pillar to the strategy that’s unlikely to change and has implications for organic growth.

Exhibit D shows market share for the top 10 builders in each large metro where NVR shows up in the data for both 2005 and 2021. In each of these markets where NVR is active, concentration of share among the top 10 builders has increased significantly over time. In my view, these large builders are leveraging scale to take share from small competitors, but given the concentration today, that strategy seems to be running out of steam. I think it will be much harder for NVR to take share from a large competitor like DHI than it is from a mom-and-pop homebuilder that completes 5 houses/year. In fact, I’ve seen multiple references from ex-employees and competitors that NVR is reaching full penetration in their major markets, and the data certainly seems to support that. If true, then the outlook for organic growth is much worse today than in 2005 if NVR isn’t willing to target new markets like Texas or Colorado. Even then, most metros across the country are more concentrated today than ever before, and I suspect NVR will struggle to steal share from local incumbents.

Despite what I view as a more challenging organic growth backdrop, I think NVR has done an exceptional job at growing and maintaining share in existing markets where they are often the largest (or one of the largest) builders in that metro. I expect that they will continue to be the dominant builder in their most important metros for decades to come, but their share of completions shouldn’t change materially, and their unit volume will just ebb and flow with industry activity – and that’s totally fine if you underwrite those expectations as an investor. Their financial track record is also excellent, with industry leading ROIC and operating margins. If they continue to emphasize regional scale and don’t deviate from their asset-light approach, I think they’ll continue to be the most profitable builder in this industry. That makes for a good segue into the secret sauce.

Asset-Light King

NVR is by far the most profitable homebuilder in this industry, and has held that title since emerging from bankruptcy in the 1990’s. The primary reason is that they’ve taken “asset light” to an extreme; they deploy less capital than any other public homebuilder to generate a dollar of operating income. Exhibit E shows NWC per controlled lot (raw and adjusted for ASPs) vs ROIC for NVR and other large builders. NVR is clearly in a world of their own.

I find it helpful to visualize the component pieces of invested capital vs NOPAT, and I’ve illustrated this in Exhibit F. NVR carries enormous cash balances so return on total capital is much less than ROIC, but I nevertheless believe this is a useful framework for understanding NVR economics. I’ve shown the split for both 2019 and 2022 but note that 2022 was clearly an outlier because A) NOPAT was likely unsustainably high, and B) invested capital was unusually low. Prior to COVID, NVRs net invested capital consisted almost entirely of inventory – finished homes and construction-in-progress (CIP) – and land/lot options.

Reducing finished home and construction-in-progress inventory is difficult. A conservative and efficient builder that isn’t building homes on spec might have slightly higher inventory turnover than average, but this isn’t where major differentiation tends to happen.

The bigger needle-mover for NWC is to control lot backlog via option contracts vs outright ownership. If an average lot costs $100k and a builder owns 100% of their controlled lot backlog with 5 years of runway, they’d need to deploy $500k to secure that backlog for every home that they sell/year. If a builder controls 100% of their lot backlog via option contracts that cost 10% of the lot purchase price, then that builder would only need to deploy $50k to secure the same backlog for every home that they sell/year. That’s a simple way to look at it, and the lot option strategy does have some offsetting COGS impact, but it’s sufficiently immaterial to largely ignore here.

Exhibit G breaks out CIP/finished homes and land/lot investments as a percentage of revenue for NVR and two other builders that own a greater percentage of their controlled lot backlog. The first observation we can make is that NVRs land/lot investments as a percentage of revenue are a small fraction of DHI/KBH, largely because they don’t own any of their lot backlog. The delta in capital intensity in that bucket is almost exactly what we’d expect to see using the math from the example above.

The second observation we can make is that NVRs CIP/finished home inventory balances are also proportionally lower than some of their large peers. It doesn’t move the needle as much for invested capital, but it certainly doesn’t hurt. The reason for this is that NVR doesn’t build homes on spec. Instead, they wait for a customer commitment, which requires that a customer secures financing and places a non-refundable deposit equivalent to ~3% of the purchase price. One Tegus expert noted that NVR doesn’t exercise lot option contracts until the commitment is received, and even then, they wait to exercise until “3-4 days prior to actually going and digging a hole, breaking ground”. Something like 90 days after the lot option is exercised and cash starts going out the door, the house is complete and remaining balances are paid. Because they don’t build on spec, NVR is rarely stuck with finished homes on their balance sheet. It’s hard to imagine how this homebuilding machine could possibly get any more capital efficient, and it’s for these reasons that NVR turns over CIP/finished home inventory 2x faster than the rest of the industry. They have such an aversion to tying up capital that another expert noted “what’s funny about NVR is they don’t own anything, honestly… even the laptops that they give everybody to use are leased”.

A natural follow up question is whether this strategy is sustainable. Is there something that could force NVR to own more of their lot backlog, drive inventory turnover lower, or lead to inflation in option contract premiums? I’m not sure there is (from 2003-2022 there was no inflation in option premiums). I’ve been told that at any point in time NVR is working with over 400 developers. Meanwhile, NVR often has 15%+ market share in a given metro, and I’d imagine that they are frequently the largest customer to any one developer. In my view, this balance of power would make it difficult for developers to change the status quo. That’s especially true if other large competitors like DHI are also leaning more on the option strategy, leaving fewer alternatives for developers. Against that backdrop, I think it’s reasonable to expect that NVR will continue to deploy very few dollars of invested capital and generate exceptional ROIC for a very long time.

One downside to this strategy is that NVR pays developers the full market price for a finished lot, while some of their competitors buy raw or semi-raw land, engage in development themselves, and capture the developer margin. Purchasing land earlier in the development process can lead to better margins via lower COGS, although it comes with more risk and ties up more capital – on balance I think that the trade-off between margins and risk/capital is one worth taking for NVR.

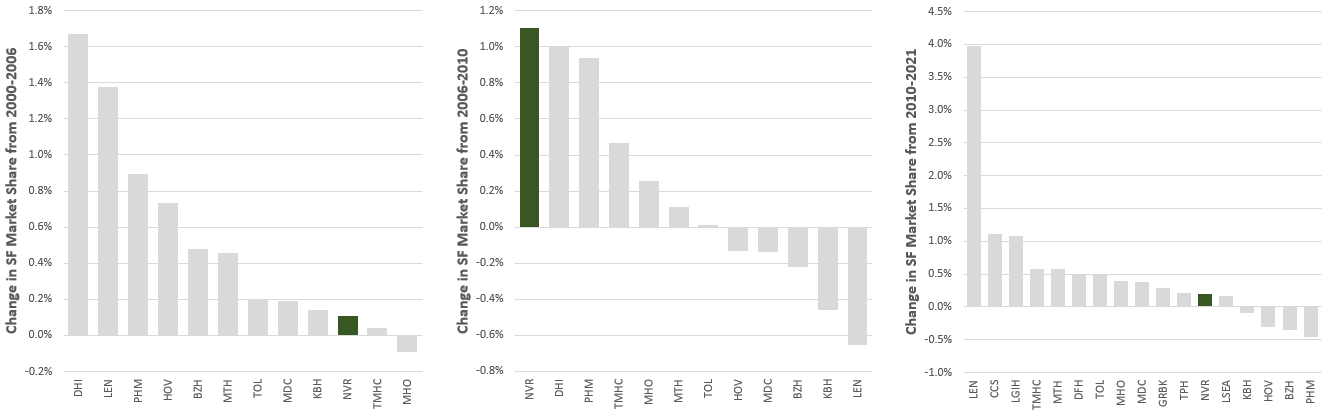

The other downside to the lot option strategy is that it probably leads to lower organic growth – we know that developers don’t love the lot option approach, which makes it difficult to enter new markets. Recall from Exhibit A above that NVRs market share was more-or-less flat prior to the GFC and has been more-or-less flat since 2010. They did gain significant share during the homebuilding winter (2006-2010), likely because other builders grappled with serious liquidity problems and NVRs approach left them with ample capital to press the gas and enter new states/metros while competitors hunkered down. But ignoring the GFC, NVR has struggled to take share relative to most of the other large builders (see Exhibit H). NVR also doesn’t have a presence in some of the fastest growing states of the last 10-20 years like Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Arizona, Texas, and Colorado – and I’ve seen no real indication that they’ve looked to penetrate these areas.

I suppose you could argue that the next time there is a housing downturn NVR’s strategy could once again lead to share gains, but as I highlighted in Part 1, homebuilder balance sheets are in a much better place today than prior to the GFC, and most metros are considerably more concentrated today than prior to the GFC.

Ultimately, I think NVR is making a trade-off between ROIC and reinvestment rates. That trade-off might make NVR’s business more resilient/profitable, but it might not be optimal. I’ll expand on this in more detail later.

Scale + Narrow Focus

In addition to their lot option strategy, a combination of scale and narrow focus has allowed NVR to differentiate themselves from other homebuilders in unique ways.

Through Ryan Homes, NVR largely focuses on entry-level housing. Among the 19 public homebuilders I evaluated in Part 1, NVR has amongst the lowest ASPs. These aren’t fancy customized units. Instead, these are relatively standardized units with similar specs. Recall from Part 1 that NVR doesn’t have a design studio – “the standard is the standard” – and they might only offer six packages to chose from, where “anything on that package is not interchangeable”. They build so many of these standardized units that they can benefit from scale in unique ways like vertically integrating into the manufacturing of certain components like trusses, wall panels, and flooring. One previous NVR employee said:

“They cut out a whole layer of cost by not using outsourced roof truss manufacturers. They buy their own lumber, have their own distribution center. So, they’re cutting out a layer of sales cost if nothing else by managing the purchase and redistribution of a lot of building materials”

According to this ex-employee, no other builder has vertically integrated “at the scale NVR is at”. NVR leases seven production facilities and owns one large production facility, where each facility serves a relatively small geographic area. It doesn’t make economic sense to build a truss and then ship it 1,000 miles, which means any trusses made at a production facility must be consumed locally. So, in this case it’s regional scale that helps them vertically integrate and reduce cost/control quality. The narrow focus on a standardized product lineup allows NVR to build hundreds/thousands of the same truss in an assembly-line like fashion instead of customizing each truss (which would obviously take longer and be less efficient).

The production facilities also act as distribution centers, which gives NVR a leg up on procurement of building supplies and appliances from third parties. Apparently, a small homebuilder will buy plumbing products from the plumbing subcontractor that they hire. The plumbing subcontractor “will buy the plumbing products from a distributor, who in turn buys from a wholesaler, who in turn buys from a manufacturer… so that’s a few layers between what the builder is paying for from the plumber and what the manufacturer sells for”. The same goes for many other products, where the homebuilder relies on a given subcontractor to procure that product on their behalf. By comparison, NVR identified that they could cut out an entire layer of cost if they just went directly to manufacturers or specialty distributors, and then purchased materials on behalf of their subcontractors to use/install. They can buy 2,000 toilets and have them all delivered to a single production facility for distribution to homesites, where other builders would have to get individual toilets delivered to each homesite if they also wanted to cut out the middleman – “other builders have no idea how to manage that”. The added benefit of placing large orders directly with manufacturers is that NVR also receives rebates from the manufacturer depending on the size of the order. “The bigger the company, the bigger the rebate… NVR has been doing this for 20 years… they’re way head of other big builders who are [only now] trying to go direct to manufacturers”. I’d note that since NVR has a narrow selection of standardized packages, they’ve also concentrated their buying with 1-2 vendors for a given product instead of dozens.

NVRs narrow focus also allows them to build homes in pods instead of spot building. Again, because of the standardized units, they can be built on tightly controlled timelines with relatively homogenous steps. When NVR signs a lot-option contract, the takedown schedule will release multiple units at a time. So, say the first five units in a community get released. NVR will buy all those lots at the exact same time and start construction on each lot at the exact same time. One ex-employee noted that this approach maximizes uptime of subcontractors, which in turn drives cost savings:

“The construction crews will come out and they’ll pour five foundations in one day… and then the plumbers will come out and they’ll plumb all five homes in a week… and that is a tremendous cost savings versus coming out to one particular home one day, and then a few days later to another home… the vendors, they gouge you for that… so, NVR can control their costs, and that’s how they stay competitive in the market”.

NVR also approaches realtor relationships differently than other builders. One expert noted that NVR did a study “and what they found was that they may have one real estate transaction with one particular agent, but they never see that agent come back and bring them a second piece of business… so based in part on that, they don’t compensate realtors like a lot of other builders do”. On a $300k home, a typical builder might pay a buyers realtor 3.0% ($9,000) in commission, whereas NVR apparently pays just 0.5% ($1,500) on that same transaction. This feels like a chicken and egg problem – do realtors not bring back a second piece of business because commissions are low, or are commissions low because realtors aren’t always a repeat channel? In any event, I can see how this approach might burn some realtors who might not direct future business NVR’s way, but NVR saves millions of dollars a year by doing this. It’s not immediately clear to me what percentage of buyers (for new homes in general or NVR specifically) use a realtor, but if it was 30% then NVR would have saved something like $50-100mn in realtor fees last year. NVR can probably get away with this because A) scale helps them market homes better than small homebuilders who have to rely more heavily on realtors than billboards, radio ads, or model homes, B) they do deep research on potential communities before investing which gives them visibility to strong demand without leaning on realtors as much, and C) it’s the sellers realtor that typically collects fees and splits those with the buyers realtor, so NVR has control over the fee dynamic. It’s possible that this approach is a contributing factor to NVR having lower organic growth (they rarely enter new markets outside of a recession) relative to other large builders, which would once again look like they’re making an explicit trade-off between growth and returns.

Much of what I’ve described above is unique to NVR and maybe a couple other large builders, but there are other scale advantages that all large homebuilders enjoy over the long tail of small competitors. For example, any large builder will exert pressure on subcontractors by making them trade off margins for volume. NVR might hire the same concrete crew to pour 200 foundations in a new community but pay them less per slab than a mom-and-pop builder might. Another expert noted that “it’s volume play… the money is steady, they pay their bills, but margins are slim” for the subcontractor. Apparently, NVR goes so far as to sign fixed-price subcontracting agreements, so they don’t assume the risk of cost overruns. A few large competitors also have in-house title and mortgage origination businesses, which obviously require scale to run, and contributes to EBIT/home at the margin – last year, NVRs title and mortgage origination business generated a 29% return on equity.

Most of the benefits from scale that I’ve outlined above are most relevant at the regional rather than the national level. So, considering NVR is the 4th largest builder in the country with significant share in the key markets they serve (15%+ in 6 metros), we should expect to see that their operating margins are among the best in the peer group (gross margins aren’t easily comparable across the peer group, so the better apples-to-apples metric to use is operating margins). That’s especially true considering some of the idiosyncratic stuff NVR does to improve margins that even some of their largest competitors don’t. Exhibit I shows historical margins for public homebuilders, and this does appear to be the case, with NVR typically having the highest – or nearly the highest – operating margins over the last 20 years. This is particularly impressive when you consider the additional cost of option contracts and the fact that NVR pays full price for finished lots.

I can’t definitively prove it, but I also suspect that NVR is sharing some of their scale economies with customers via lower ASPs instead of accruing 100% of that benefit in margins. That would jive with the comment above from an ex-NVR employee about how “NVR can control their costs, and that’s how they stay competitive in the market”. To test that hypothesis, I compared ASP inflation for NVR vs the peer group and across industry-wide ASPs for new detached single-family homes (and industry-wide median selling price). What I found was that NVRs ASP inflation over the last decade was lower than any other builder in the peer group and tended to be lower than industry-wide ASP inflation over almost any period since 2000. Outside of looking at ASPs I couldn’t think of another way to validate the hypothesis, but it seems to hold water (if you have insight to share on this front, please reach out). If true, then that helps keep NVR competitive in their markets and helps explain why they consistently maintain dominant market share in key metros.

Management and Governance

Dwight Schar retired from the CEO role in 2005 but stuck around as Chairman of the Board until last year. Paul Saville took over as CEO in 2005 after joining Ryan Homes in the 1980s and holding several senior leadership roles over the subsequent two decades. Paul retired from his role as CEO last year and became Chairman of the Board in Dwight’s place. Eugene Bredow took over for Paul as CEO. Eugene joined NVR in 2004. He was the Chief Accounting Officer, SVP and Chief Administrative Officer, and most recently the President of NVR Mortgage. It looks like the transition strategy is to have the outgoing CEO sit on the board and help mentor the incoming CEO, which helps preserve institutional knowledge and ensure consistent strategy/culture through transitions. I don’t have a strong opinion on Eugene one way or another, but find it encouraging that Paul is sticking around.

Roughly 70% of NEO comp is paid through an LTIP where executives get options that vest in equal installments over four years. Half of the options vest based exclusively on continued employment, while the other half vests based on continued employment and return on capital performance relative to the peer group. For 100% of the options to vest, NVR must have a return on capital in the top 3 of public homebuilders they measure against (all the usual suspects). If they are below the 50th percentile then none of the relevant options vest. We know that NVR has consistently ranked #1 in return on capital relative to the peer group, so executives always enjoy maximum vesting. Combined with the fact that the tenure of most NEOs is high (often decades), inside ownership is extraordinary. Including unvested LTIP awards, the five NEOs from the proxy statement last year owned roughly 9.5% of the business valued at $1.7bn, while the board (including Dwight) owned an additional 2.8% of the business valued at nearly $500mn. If we strip out Dwight and Paul, the NEOs/board own about 4.4% of the business worth ~$800mn.

One knock on the current incentive structure is that it emphasizes ROIC over NPV. We know that NVRs ROIC is the highest in their peer group, and often by a huge margin. The executive team is clearly incentivized to keep it that way. As such, I think they’d turn down opportunities to deploy incremental capital at returns lower than their current return on capital but still much higher than their cost of capital. Exhibit K shows sources and uses of cash over the last decade, and total capex, M&A, and NWC investments (basically growth capital) amounted to just $1,158mn, which represents a reinvestment rate of just 14%. I feel reasonably confident that NVR could increase their reinvestment rate by 10% at an incremental return on capital that is still a multiple of their cost of capital, which would then create more value for equity owners. But given the conservative culture that Dwight created, and that Paul ran with for over a decade, I think their capital allocation behavior is unlikely to change.

I suppose the benefit of a low reinvestment rate is that NVR has returned a wild amount of FCF back to investors via buybacks. In fact, over the last two decades they’ve reduced their w.a. diluted share count by 67% (Exhibit L). Over the same period, they spent more than $9.0bn buying back shares at a weighted average price of just $1,572/share vs the current price of roughly $5,000/share. Obviously, these buybacks have been very accretive, but I think it’s important to differentiate between systematic buybacks and opportunistic buybacks. In this case, the buyback program looks systematic rather than opportunistic – looking through the historical data I don’t think the management team is regularly assessing fair value for their business, leaning into buybacks when the stock looks cheap, and pairing back when the stock looks expensive. So, the outcome of the buyback program has been exceptional, but I think that might have a little more to do with luck than capital allocation prowess. Unfortunately, NVR doesn’t do earnings calls and executives aren’t very public, so it’s more difficult than normal to assess their thinking over time. In any event, I wouldn’t expect their buyback program to be nearly as accretive in the future as it has been historically now that it’s well understood that NVR is a best-in-class builder and valuation is more likely to reflect that view.

Financial Position

The conservative culture at NVR extends to the balance sheet as well. Since 2000 NVR has almost always carried a net cash position, and at the end of 2022 that net cash position was at a record ~$1.6bn (Exhibit M). The only debt they have today are 3.0% Senior Notes that mature in 2030, which gives them a ton of flexibility to continue repurchasing shares even if their was a recession tomorrow and FCF fell considerably. To that last point, NVR has never generated negative cash flow from operations – not even through the GFC. I’d also point out that during the GFC NVR organically expanded into a few new states/metros while other builders paired back (NVRs market share more than doubled, and they never gave that back). With significant liquidity today, they’d be very well positioned to enter new markets if there was a housing downturn again any time soon (even with balance sheets across the large peer group that look reasonably healthy). They are one of the few builders whose balance sheet and asset-light approach allow them to be aggressively countercyclical. That option certainly has some value, although the net cash balance is a drag on ROE in the meantime.

Valuation

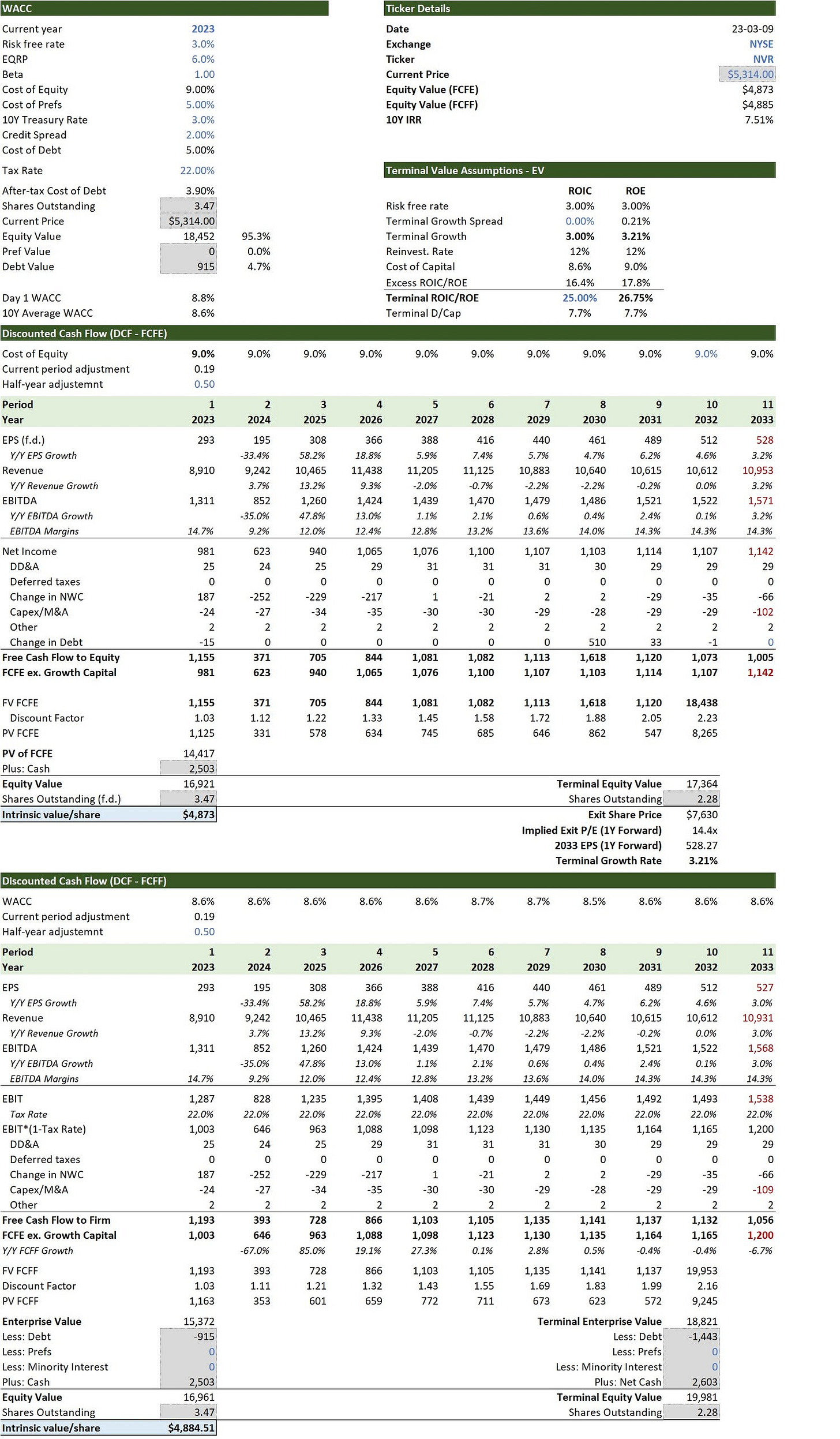

Unfortunately, even a best-in-class builder like NVR is subject to the ebbs and flows of industry activity – they are at the mercy of the macro. As a result, getting the industry call right is likely more important than having a slightly differentiated view on margins or market share. As I described in Part 1, I think it’s really challenging to get the macro right – there are too many hard-to-predict key drivers and the range of outcomes is wide. Nevertheless, I take a stab at base case assumptions with the caveat that the margin of error is high. I’ve also laid out assumptions – and the implied price – that I’d be very comfortable underwriting. You can find my full model below.

Base case

In the base case I assume that industry total completions fall in 2023, recover in 2024/2025 and then gradually converge with the run-rate required once the market is balanced. In this case, I’m assuming a current housing deficit of about 2.5mn units (roughly the mid-point of the 1.8mn and 3.5mn goal posts I laid out in Part 1). I assume that the single-family market loses modest share but represents ~70% of total completions over the next decade. I also think that NVR has a reasonable chance of gaining some share over time, particularly if the overall SF market pulls back in the near-term. I’m modelling a 12% reduction in ASPs from 2022-2024, but a 2.5% CAGR from 2019-2032. Finally, I think EBIT margins could compress in the near term on the back of lower volume/ASPs but suspect mid-cycle margins are likely to be in the low-teens (which translates into a low-40% ROIC). I’ve illustrated my base case assumptions in Exhibit N.

In the base case I use a 9.0% cost of equity, 3% terminal growth rate, and 25% terminal ROIC, which implies that terminal P/E is ~14.5x. Exhibit O shows a snapshot of my DCF output tab. Using these assumptions, I estimate that fair value is ~$4,850/share, which happens to be ~10% lower than where NVR is trading today. Unless you have a meaningfully different view on any of the key drivers outlined above, it’s difficult to argue that NVR represents great value at today’s share price, particularly considering the wide range of outcomes and near-term macro risk.

What would I comfortably underwrite to become an investor?

In Exhibit P I illustrate the assumptions I’d comfortably take the over on. In this scenario, I have industry completions falling materially over time, NVR gaining minimal SF share, a 1.5% ASP CAGR from 2019-2032, and EBIT margins that are 1.5% lower than the base case (lower than what I’d consider true mid-cycle margins). It’s hard to see how this would play out – for example, if there was any housing deficit today, these industry completion estimates would not be sufficient to work off a deficit. If the deficit remains, it’s unlikely that ASPs/margins would fall. I also hold my terminal assumptions (9.0% cost of equity, 3.0% terminal growth rate, and 25% terminal ROIC) constant, but if a deficit persisted and ASPs in 2032 were unchanged from 2022, then that terminal growth rate would likely be too low.

Using these assumptions, I arrive at a fair value estimate of ~$3,700/share – this is the price I’d be keen to become an investor in NVR. We’re obviously a far cry from that today, but NVR last traded at $3,700/share in mid-2022. A change in sentiment or a string of bad quarterly results in the sector could easily take us back there.

Sensitivity Analysis

The obvious two variables to sensitize the base case to are total industry completions and NVR’s single-family market share, so I ran that data table in Exhibit Q while holding everything else in the base case constant. If you believe my other estimates are reasonable but want to argue that my base case is too punitive (green shaded area), you must assume that industry completions are substantially higher over the next decade and that NVR gains significant market share in that environment. Seeing as they struggled to gain share over the last decade, that seems unlikely. I’d also note that for the industry to complete an average of 1,500k units/year over the next decade, you’d have to assume something like a 4.0mn unit deficit today (holding other assumptions constant) or some combination of higher population growth/fewer adults per household. I don’t think any of those outcomes are impossible, but you really need a lot to go right to generate any excess return over the cost of equity I’m using. On the flipside, you don’t need a lot to go wrong to realize permanent capital impairment – if NVR’s market share remained constant and average industry completions came in under my base case then fair value would be >25% lower than the current price.

Exhibit R holds completions and market share constant and sensitizes fair value to ASP CAGRs (2019-2032) and terminal Homebuilding EBIT margins. I think the range of outcomes here is narrower than the data table above. Given material and labor inflation, I think it’s unlikely that ASPs grow slower from 2019-2032 than they did from 2000-2019, but given NVRs history of focusing on affordable homes (and likely sharing some scale economies), I’d be surprised if the ASP CAGR was 4%+. I also think it would be tough to make an argument for 16% terminal EBIT margins once the market is in balance, but it seems incredibly unlikely that NVR – with the highest operating margins in industry – would have margins of 10% given the readthrough for other builders’ economics. Most combinations of assumptions between those goal posts gets you a fair value estimate close enough to the current price (if not slightly below).

Conclusion

There is no doubt that NVR is the most profitable public homebuilder with a dominant position and strong moats in their existing markets. Similarly, they have the strongest balance sheet in the peer group, which is an enviable position to be in ahead of what might be a weaker housing market in 2023/2024. Unfortunately, I think all of this is well understood by the market – at a minimum, implied expectations seem to reflect these facts, unless my assumptions about industry activity levels from Part 1 prove to be materially incorrect. I’d love to own a piece of this business at some point, but the price I’d be interested in making that happen is 30% lower than the current share price, so for now it goes on the watchlist.

As always, I encourage you to reach out if you have a different view or would like to discuss any of my assumptions in more detail. You can reach me at the10thmanbb@gmail.com, in the comments below, or on Twitter.