We urge you to read Part 1 of the series if you’re unfamiliar with the video game space, particularly because many of the themes we discuss are both implicitly and explicitly reflected in our assessment of EA 0.00%↑.

During our research process we considered a very wide range of potential value drivers and detractors, and while we feel comfortable in our assessment, we’re bound to have missed something. As such, please don’t hesitate to reach out with criticisms or questions at the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

Investment Thesis

EA has a number of competitive advantages that we believe will lead to both revenue growth and margin expansion beyond what the current share price implies, namely:

Fantastic moats around their most important IP, primarily because of exclusive licenses and great brands.

Decentralized creative teams, but centralization of many other core functions driven by the One EA initiative. The internally developed Frostbite engine is one product of that initiative that is hard to replicate and should yield multiple long-term cost and revenue benefits. This centralization is hard to replicate without scale, and even then it’s difficult.

A rare breadth in the game catalog, even among the large publisher peer group. That breadth makes it easier to bundle a traditionally unbundled service through a subscription offering, which we think yields benefits for both EA and players.

EA also benefits from a number of secular industry trends like the shift to digital distribution, growth in global content consumption, in-game sales growth, increasing eSport popularity, and a potential reduction in distribution platform fees.

In addition to great industry and company-specific tailwinds, EA has a significant net cash position, which we expect will enable a combination of M&A and a meaningful increase in distributions to shareholders. The company is already taking tangible steps to make that happen, but we think it’s unlikely that the full potential of these corporate actions are reflected in the current share price.

We’re cognizant of gamer criticisms, internal challenges with the Frostbite transition, some historical missteps with distribution, mobile development void, concerns about the sport category, and loot box regulation. In fact, we spend a lot of time discussing these pitfalls in the post. And while these are all valid concerns, we’ve concluded that either A) EA is/has taken steps to address these issues, and/or B) a significant portion of those views are already being reflected in the current price.

Our base case suggests fair value of $185-190/share, which represents 30-35% upside to the current price of $142/share. Our scenario analysis also suggests that risk is meaningfully skewed to the upside.

Content

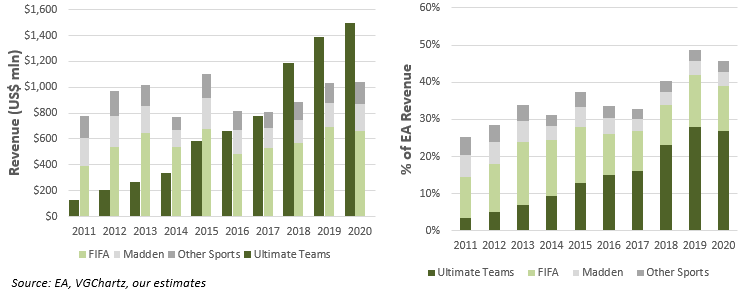

EA is best known for its sport franchises like FIFA, Madden, NHL, and PGA, which they’ve been making since the 1990’s. The great thing about these titles is that a new version is released annually, which creates a robust recurring revenue stream. These are all paid games, most of which offer additional paid content, specifically in the form of Ultimate Team mode. Ultimate Team mode is basically an eSport league that is technically F2P (included with game purchase), but effectively pay-to-win. To be competitive, players need to purchase “player packs” to build good teams, and everyone seems to do this. In fact, revenue from Ultimate Team is now significantly higher than total revenue from all unit sales of sport titles at EA, and is a primary driver behind EA’s total top line growth over the last decade (Exhibit A). FIFA and FIFA Ultimate Team are clearly the most important contributors to overall revenue, with Madden being in distant second place.

The only other title that EA reports as having generated more than 10% of total revenue in a given year is Battlefield, which we’ve always viewed as a less successful Call of Duty: based on VGChartz data, Call of Duty unit sales are typically 5.0x greater than Battlefield (2009-2018). Nevertheless, Battlefield clearly has a loyal following, and is one of those rare enduring franchises that’s been successful across decades.

Unlike some of the other publishers, where just 2-4 titles generate >70% of revenue, EA has a more diverse game slate. We estimate that Battlefield and all the sport titles generate slightly more than 50% of revenue today, and EA has dozens of other relatively big games in the lineup like Star Wars, Sims, Need4Speed, Apex Legends, Rocket Arena, Command & Conquer, and Mass Effect. If one title fails, it doesn’t sink the ship.

Most of the titles highlighted above fall into the traditional paid-game category, but Apex Legends was EA’s foray into true F2P, and it’s worked out very well so far. Apex Legends is a spin-off of Titanfall, which was an underperforming franchise after an initial release in 2014 and a follow-up in 2016. Given the underwhelming reception of Titanfall, and seeing the success of F2P battle royale games in the market, EA reallocated the Titanfall development team to work on their own F2P battle royale title. EA indicated that Apex Legends now has 8-10 mln weekly average users, and that the game is generating operating margins in the 60% range, vs. the 20-40% that a stand-alone paid game like Titanfall would have generated.

Lastly, the EA game slate is predominately geared toward console players, and that hasn’t changed materially over the last decade. This isn’t that surprising, given that most sport titles are dominated by console. EA has rolled out mobile versions of FIFA, Madden, Sims, and Star Wars, but they haven’t been major drivers of top line growth.

Loot Boxes

As we touched on briefly above, a primary monetization mechanism for EA’s Ultimate Team mode is the sale of player packs. These player packs are often considered to be loot boxes, which is a subject that has received significant regulatory and legislative attention in recent years. The biggest concern is whether or not loot box mechanics constitute gambling. If they do, it’s possible that they become more heavily regulated and restricted in games, which would obviously be bad for EA.

One specific area of concern is how acceptable loot boxes are for children, and in some big markets, like the United States, bills have been introduced at the federal level to limit the use of loot boxes in games played by minors. At a minimum, the game rating might have to reflect these mechanics. Some other countries have already established positions that deem certain loot boxes to be gambling, and EA might have to disable Ultimate Team mode in those jurisdictions under the current form (Belgium, and the Netherlands). Other countries have taken a more lax stance (France, New Zealand, and Poland), so no immediate changes should be expected. The National Law Review also pointed out that “in 2018, state legislatures in at least four states (California, Hawaii, Minnesota, and Washington) introduced bills aimed at regulating loot box sales. All failed to pass.“

This is clearly muddy water. In due course, we expect that new regulations in most markets will probably introduce at least some restrictions and new disclosure requirements, which could be modestly negative for EA. That being said, we note that the demographic shift in gaming reduces this downside (more adults playing games than kids), and monetization mechanisms, disclosures, and parental controls can adjust very quickly to comply with new laws. In the base case, we’d assume that regulations are either light or that EA can readily adapt to avoid a noticeable negative hit to ARPU. In the bear case, this becomes a more meaningful challenge for EA, which reduces margin upside and revenue growth.

Competitive Position - Licenses

A significant portion of EA’s revenue comes from games that lean on third-party licenses, such as sport titles, Star Wars, and The Simpsons. In aggregate, these games probably account for 50% of revenue today. This licensing dynamic has its pros and cons, but we believe it’s largely beneficial to EA.

Licenses are particularly valuable when they are exclusive, meaning no other developer can use the content in competing games. That’s great news for EA, because they’ve secured exclusive license agreements for their most popular franchises, including FIFA and Madden. The primary downside of having to secure an exclusive license from a third party is that the licensor is going to demand their pound of flesh, and when license agreements come up for renewal, the licensor will want to maximize value through a competitive bidding process. All the developers sitting on the sidelines during the initial license tenor are going to be chomping at the bit to get a FIFA license, for example. EA highlights this risk in their annual report (emphasis our own):

“Many of our products and services are based on or incorporate intellectual property owned by others. For example, our EA Sports products include rights licensed from major sports leagues, teams and players’ associations and our Star Wars products include rights licensed from Disney. Competition for these licenses and rights is intense. If we are unable to maintain these licenses and rights or obtain additional licenses or rights with significant commercial value, our ability to develop successful and engaging products and services may be adversely affected and our revenue, profitability and cash flows may decline significantly. Competition for these licenses has increased, and may continue to increase, the amounts that we must pay to licensors and developers, through higher minimum guarantees or royalty rates, which could significantly increase our costs and reduce our profitability.”

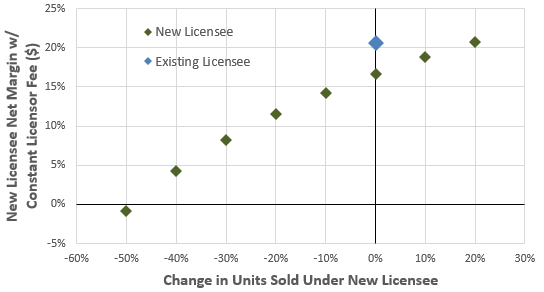

As we think about this, it seems that there are two important questions to ask, with the first being: what factors does the licensor weigh when allocating an exclusive license? To answer this question, we need to understand how license agreements work. Most licenses are revenue share deals with some minimum guarantee, so the licensor cares about the Revenue Share function: MAX(volume * price * licensor royalty, minimum revenue guarantee). EA tells us that the licensor fees always exceed minimum guarantees, so the real differentiating factor in a publisher bid is the licensor royalty. But it’s not that simple. A new developer might make a worse game than the incumbent, or fail to market the new game effectively, either of which would result in fewer unit sales than the status quo. That’s especially true if the incumbent keeps releasing highly rated titles. If the new developer sells 20% fewer units, then they would need to bid a royalty rate much higher than the incumbent for the licensor royalty fee (in absolute dollars) to remain constant (assuming the minimum guarantee is <50% of the total royalty received today, which the data suggests). In Exhibit C, we provide an illustrative example of how the royalty rate needs to change for a given expected change in volume for the licensor to be agnostic between the incumbent and a new developer. We conclude that even though price is important, the licensor must also seriously consider how changing developers could impact game quality and unit sales.

The second question we need to ask is what can other developers afford to pay for a license relative to an EA bid? If the incumbent developer is making a well-received game today, then the licensor might expect lower unit sales after the switch, which drives up the royalty rate bid. In Exhibit D we illustrate what might happen to the new developer/licensee net margin under various scenarios, and compare that to the incumbent net margin. We assume some modest operating leverage in this illustration, and a 15% increase in development costs for the new entrant vs. incumbent. In our illustration, if the licensor expects unit sales to fall by 20%, then the new bidder has to accept a net margin of nearly 10% to succeed in acquiring the license, which is roughly half of the incumbent’s net margin. When we look at net margins for ATVI and TTWO, we note that this decision would be margin dilutive, and might not stack up well compared to other opportunities those companies have. On the flip side, if a new developer creates a better game, and sees a 20% uplift in unit sales, then the new developers net margin will be comparable to the incumbent, and they’ll more aggressively bid for the license.

One last thing to consider on this topic is that a new developer will need 2-4 years to produce a new game like FIFA, which means EA would continue to make a few additional FIFA titles after losing the license renewal. In that scenario, EA would be incentivized to optimize for profit, and not revenue, and they could do this by underinvesting in the remaining FIFA titles (lower R&D and S&M expense). This could erode the “brand value” and reduce the licensor fee during the transition (relative to status quo), which exacerbates the trade-offs a licensor and new bidder need to make in Exhibit C and D.

Going through this exercise helps us understand why licensors (for exclusive licenses) rarely switch developers when a game is performing well. On the flipside, if a game is performing poorly, competition for a license renewal should be fierce, and the incumbent is much more likely to lose the renewal bid, particularly if the forecast for unit sales under a new developer is higher than that of the incumbent.

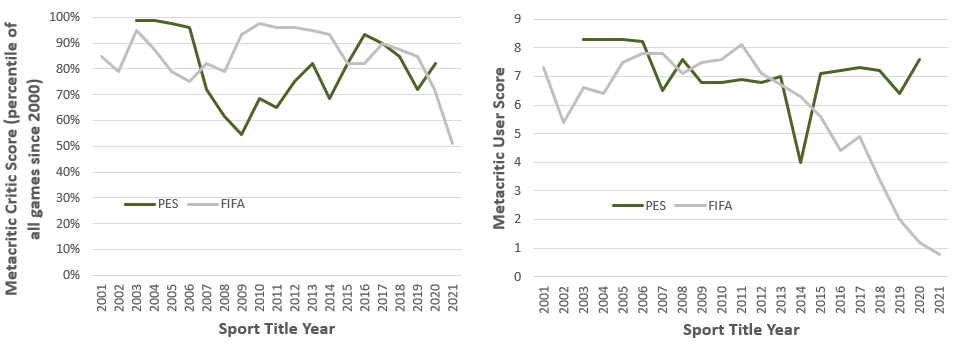

With all that in mind, we try to understand what might happen to the FIFA and Madden licenses (EA’s two biggest) when they come up for renewal. We start by looking at game ratings, as we’ve shown in Exhibit E, and see that user ratings on Metacritic were consistently around the average for both titles from 2001-2011. After that, user ratings dropped off a cliff, with Madden 21 receiving the lowest ever user rating on Metacritic, and FIFA 21 not far behind.

In addition to user ratings, Metacritic critic ratings have also dropped off a cliff for both franchises, particularly for the 2020/21 releases.

When we read critic and user reviews, two common reasons emerge for the deteriorating ratings. First, consensus seems to be that the games “aren’t innovating enough” over time – EA is just pushing out the same game with new players. In other words, Madden 21 is basically the same thing as Madden 20, so customers feel cheated. For context, annual development costs for Madden are in the $50-75 mln range, which is much lower than $175-200 mln in annual development costs for something like Call of Duty. The second reason is that the most popular game modes are becoming increasingly pay-to-win (Ultimate Team), which clearly irks some users that give low scores. In Exhibit G, we plotted Metacritic user scores (2001-2021 titles for each franchise) vs. Ultimate Team revenue as proportion of total sport-related revenue, and the inverse relationship looks pretty strong (r2 of 75-80%). Correlation doesn’t always mean causation, but this data is also supported by commentary from user and critic reviews, so we think it’s safe to draw the conclusion that: EA has stopped innovating around the core game, and has increasingly focused on monetizing players through eSports, which has simultaneously been very successful and created a growing community of angry users.

Ignoring Ultimate Team, revenue from FIFA and Madden has grown at some low single-digit rate over the last decade, which implies that the total user pool isn’t shrinking, despite the dismal ratings – oh, the beauty of a captive market. If we include Ultimate Team revenue, total sport-related revenue has grown 2.0x faster than the global console/PC market for the last decade. From the licensor perspective, royalties are a boomin’. Who cares if game ratings are falling if the user base isn’t shrinking and ARPU is growing enough to generate royalty growth of +10%/year?

At first glance, the NFL (and related parties) clearly aren’t that bothered by low ratings, because they just renewed their exclusive license with EA earlier this year until mid-2026. However, TTWO, which hasn’t produced a football title since EA secured the exclusive licenses in 2004, signed an agreement with the NFL players association that will allow them to create non-simulation football games using real players. In our view, the football licensors are happy that royalty revenue is increasing, but are worried about the long-term success of the franchise if users and critics remain unhappy, so are looking to re-introduce competition with a second developer. If TTWO can create good content for non-simulation football games, it might de-risk the decision to grant TTWO the exclusive license for simulation games once the license comes up for renewal in 6 years. Alternatively, it might create a more competitive environment for the license, which could push up royalty rates. Either way, we expect the renewed competition to be negative for profitability of the Madden franchise eventually, and prospective investors should bake this into their assessment of fair value for EA in multiple scenarios.

Despite similarly poor ratings for FIFA, we think that EA’s competitive position for that franchise is much better than for Madden. EA tells us that Madden relies on just 3 license agreements (NHL is the same), vs. FIFA which currently has over 420 licenses with counterparties all over the world. Not only are there hundreds of license agreements behind FIFA, but the terms of those license agreements are staggered. For a competitor to create a simulated soccer game with comparable depth, not only would they have to go secure 420 licenses (a massive feat in and of itself), but they’d also have to do so slowly as each license expires. Not every license is exclusive, but many of the important ones are. As a result, the first iteration of a competing title would have less content than EA’s FIFA game today, which would make it objectively worse, all else equal. For the FIFA franchise, the most important license agreements are with counterparties like FIFA and Premier League, and the last FIFA license was secured under a 10-year term that expires at the end of 2022 (link). It’s possible that some soccer licensors follow the NFL’s footsteps and look for new developers, but we don’t think any major developers will take the leap, as we explain below.

The Pro Evolution Soccer series (PES), developed by Konami, has been the only real franchise to compete with FIFA over the last twenty years. When we look at critic and user ratings, it seems that PES games were equally compelling for many years, and currently garner higher reviews than FIFA (Exhibit H).

Knowing nothing else, and given the comparable or better ratings, we would have expected PES and FIFA unit sales to be similar; and once upon a time, they were. In 2009, VGChartz data shows that FIFA console sales were ~9.0 mln units, while PES unit sales were ~7.0 mln. Today, however, FIFA sells something like 20.0x more units every year than PES (Exhibit I).

FIFA’s dominance over PES is probably some combination of better initial gameplay, orders of magnitude more exclusive content, marketing and brand awareness, and Ultimate Team participation. In particular, PES has struggled to secure third-party licenses anywhere close to what FIFA has, and they’ve been trying for literally decades. A new potential bidder for a single exclusive license is going to look at all that, see how PES has fared, and throw up their hands in defeat. Just to break-even on a new soccer title with comparable development and marketing expenses as the existing FIFA franchise, we estimate that a new entrant would need to sell more than 4.0-5.0 mln units/year. With PES at ~500k, that’s a tough assumption to underwrite. All told, we think the FIFA franchise has to be one of the most defendable games we’ve looked at, and an EA investor can probably rest easy knowing they’ve locked down that market.

Many other EA sport titles, like NHL and NBA, don’t have exclusive licenses, and compete directly with other franchises like TTWO’s respective 2K series. Where EA dominates in soccer, TTWO dominates in basketball, and the TTWO NBA 2K franchise dwarfs every comparable EA NBA Live release. In 2019, TTWO signed a 7-year licensing deal with the NBA worth up to $1.1 bln. Coincidentally, even though EA has a license to use NBA content, they have not released an NBA title since the September, 2018 release of NBA Live 19. Other NBA Live titles have failed to launch before (2012, 2013, and 2017), but we suspect one reason they axed NBA Live 2020 is because they didn’t expect revenue from game sales to sufficiently exceed royalties and other costs. The read-through here is that license royalties can be a barrier to entry if they materially increase the breakeven unit-sale-threshold for competitors, which makes scale matter a lot. That sucks for NBA Live, but it’s great news for FIFA. And because soccer is literally the biggest sport in the world, that’s great news for EA.

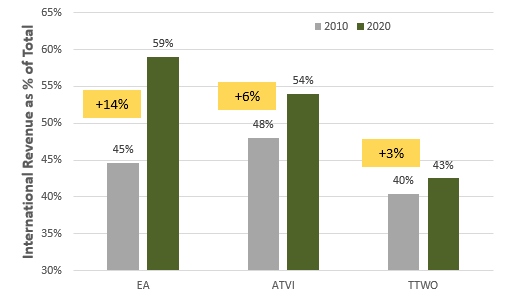

As an aside, it’s worth mentioning that ratings for all sport titles, including those not produced by EA, have all deteriorated in the last decade (NBA 2K21 had a user rating of 0.7). It’s possible that the market for sport video games is saturated, and room for innovation is just de minimis. We worry that the sport category might see lower growth than the broader market in terms of unit sales, which could lead to lower market share in the future. On the flip side, there might be a very long runway for unit sale growth (and ARPU) in international markets for globally popular sports like soccer, particularly as video game adoption increases in places like Latin America, Africa, and Asia. In Exhibit J we can see that EA’s revenue growth is predominately coming from outside North America, but also that global content revenue is heavily weighted toward North America, Europe, and wealthy Asian countries. In fact, the trailing 10-year revenue CAGR for EA in North America is only ~1%, while internationally it’s 7%. This supports the idea that the runway for growth from franchises like FIFA could still be quite healthy in Latin America/Africa/Asia in the decades to come (both from a MAU and ARPU perspective).

We also looked at international revenue as a percentage of total revenue for EA, ATVI, and TTWO (Exhibit K). The international segment has been growing proportionally faster for EA than these other competitors, and is now a much larger share of the total. This data alleviates some of our concern that the sport category is saturated in North America, and gives us some comfort that global markets are still under-penetrated. It’s likely that EA can continue to enjoy strong organic revenue growth as a result, particularly given the big competitive moat around their most important franchise.

Competitive Position - Everything Else

As we highlighted for ATVI (link), we think EA receives some brand and scale benefits across a number of its key franchises, but we won’t hash that out again here. Rather, we want to highlight some of the incremental things we learned in our research.

One unique thing about EA, relative to other publishers, is that they have become increasingly centralized. One of EA’s strategic pillars of the last decade was the One EA Initiative, which aimed to unify game development, marketing, publishing, and analytics under centralized teams or platforms for all games, which allows EA to benefit from scale economies. One component of this that we find particularly interesting is the internally developed game engine, called Frostbite, which EA is trying to use for all of its games. The Frostbite engine was originally created in 2008 for Battlefield, but EA has slowly adapted it to run other games like FIFA, Madden, Need4Speed, and Star Wars. Having a standardized engine running multiple franchises clearly reduces relative R&D expenses (it’s basically an internal Unity or Unreal engine), and Exhibit L shows that R&D as a percentage of revenue for EA has improved meaningfully versus their peers as Frostbite has gained share internally. Most of EA’s mobile titles are developed on Unity today, but they hope to ultimately transition all mobile development to Frostbite, which could result in additional development cost efficiency gains at the margin.

To elaborate on this, there appear to be three primary reasons that operating under a single engine can lead to cost efficiencies:

Economies of scale on new internally developed technology: any new functionality is immediately usable by all development teams, versus creating the same new feature from scratch for a dozen engines.

More easily handle third-party technology shifts: when a new console is released, EA just has to enable Frostbite to work on those new consoles, versus the 26 different game engines they used to have.

Flexibility for labor: employees can switch studios (work on new games) and not have to climb a 6-month learning curve to figure out a new engine. In theory this should help with employee retention, sharing of best practices, and modestly lower per unit labor costs.

In our view, the One EA initiative, with an emphasis on Frostbite, is one reason that EA has the highest net margins and ROE in the peer group today, and is simultaneously costly and time consuming to replicate, even for big competitors. There have been some notable challenges with Frostbite adoption internally at EA, which critics might argue is a bad thing. That said, we expect that Frostbite will continuously improve over time, and those kinks to be worked out. The centralized engine might also make it easier for EA to experiment internally with more new titles or partner with independent creative teams. We aren’t game engine experts, but we can’t help but think that Frostbite could be a real, if not small competitor to Unity or Unreal. At the very least, if EA eventually rolls out Frostbite for its own mobile games, they might be better positioned to work with external mobile developers and address the lack of revenue growth in their mobile division. We don’t reflect any value for this in our base case, but it’s an interesting angle to monitor.

The one downside of centralizing something like the game engine is that your games will have a similar look and feel, particularly in the early days. For example, even though we haven’t played either game, we hear that Star Wars is basically just Battlefield with Storm Troopers. Transitioning to Frostbite, away from some other engine, might also create people frictions. That’s exactly what happened with Anthem, which BioWare launched in 2019 to horrible reviews/sales. One of the oft quoted explanations for this failure is that the BioWare team was forced to use Frostbite for the first time, and found it difficult to learn effectively in the short development window. Despite some of these issues, we believe the Frostbite pros drastically outweigh the cons. The growing pains with transitioning to Frostbite also highlight how challenging it might be for other developers to follow that path.

The One EA initiative also aims to improve S&M (marketing, publishing, analytics, etc) efficiency, and it’s worth illustrating this in Exhibit M. EA has seen S&M intensity fall relative to its two big competitors, which both run more decentralized models. Centralizing these processes requires scale and lots of time, and we don’t really expect any competitors to catch-up inside of ten years – put differently, we expect that EA will continue to earn outsized returns relative to peers, all else equal.

Lastly, we’re coming around to the idea that scale, in terms of the game catalog, can better position a publisher to offer subscription services like EA Play. A small publisher with one hit franchise can’t turnaround and offer a subscription in the same way that EA can with their dozens of big games. Instead, the small publisher has to work with a third-party subscription provider, which we suspect has worse unit economics. This is a low conviction idea for us, but also a potentially meaningful advantage for the big incumbents, and we expand on this in the next section.

Strategy

From fiscal 2014 to 2019, EA highlighted three core strategic pillars: Players First, Commitment to Digital, and One EA. In our view, the Players First pillar was a bit of a farce: they introduced a largely pay-to-win game mode for sport franchises that rubbed a lot of players the wrong way; they pulled content from Steam to save on the platform fee, but then made PC games much less accessible to players by forcing them to use Origin; and, they have a track record of rushing, underinvesting, or missing the mark on a few games (Anthem/Madden/Titanfall/Mass Effect). There are also some bright spots, like Apex Legends, but we generally sympathize with the view that EA has not always put players first -although we’re sure they try. On the flipside, they’ve executed very well on the Commitment to Digital and One EA, and this is one reason why margins and returns have improved so drastically in the last 5 years.

In 2020, EA highlighted that their new strategy is “to create games and content, powered by services, delivered to a large, global audience”. In many ways, we read that to mean “harvest mode”. While EA has added some new content to their portfolio in recent years, it’s clear that they’ve largely focused on leveraging existing IP in new ways (live services) to engage existing players more deeply. Whether it’s FIFA, Madden, Battlefield, Apex Legends, or Star Wars, EA is clearly increasing their focus on driving in-game sales and selling those games into more markets. The incremental operating margins on DLC/MTX should be significantly higher than the operating margin on game sales, so we like this approach a lot, even though we worry about pay-to-win monetization. We expect that EA’s focus will be to maintain or slightly grow unit sales from existing franchises, while driving deeper engagement and higher ARPU with those users, and very selectively experimenting with new titles.

One new way that EA is distributing content is through their EA Play subscription service. We touched on this under Theme 8 in Part 1, but it’s worth slightly expanding on here, particularly as our own view evolves. There are two tiers to EA Play: the first is EA Play at $30-60/year and gives subscribers unlimited access to older games; the second is EA Play Pro at $100-180/year and gives subscribers access to both new and old games. In our view, these subscription services are a good way for a publisher to better monetize their entire catalog, particularly older titles that consumers might have been unlikely to outright purchase today - hence “harvest mode”. For new titles, EA is effectively bundling a traditionally unbundled service, which might actually increase market share (higher ARPU and MAU). Shishir Mehrotra wrote a great piece titled the Four Myths of Bundling, and his first thesis resonated with us: “When done well, bundling produces value for both consumers and providers by giving access for (and revenue from) Casual Fans“. In this case, it seems likely that EA Play Pro is a pillar in the strategy to create incremental value from Casual Fans, and we like this approach a lot. At last mark, EA Play already had in excess of 6.5 mln paid subscribers.

We note that M&A has not been a major part of the strategy under this CEO until very recently – it’s been more than a decade since they pursued any large transactions. The bid for Codemasters changes that. As it stands, it looks like EA is paying 50x T12M EBITDA for Codemasters, which is a lot. On the flip side: Codemasters’ EBITDA has grown at a trailing 3-year CAGR of >40%, EA can introduce that content to EA Play (makes EA Play better), One EA centralization can likely result in some cost synergies, and EA can probably afford to invest more in R&D and S&M per unit than Codemasters as a standalone entity (all else equal) to drive revenue synergies. Our very rudimentary back-of-the-napkin calculations indicate that the acquisition is probably a modestly better use of cash than a distribution to shareholders (either through buybacks or dividend), but an obviously better use of cash than leaving it on the balance sheet. We’re inclined to reserve judgement on the success of this acquisition or general M&A competence of management, but at a minimum, it’s positive to see EA deploy vs. accrue capital.

Performance

As we’ve touched on at multiple points in this blog post, ratings for a number of EA’s core franchises have deteriorated meaningfully in the last 5-10 years, which has probably led to sup-par unit sales growth. Lots of negative criticisms are also aimed at EA’s pay-to-win monetization mechanisms, and there have been a number of large title flops as EA has transitioned more franchises to Frostbite. In addition, EA’s PC business has performed relatively poorly because of the decision to pull content from Steam earlier in the decade, and a lack of new content. Similarly, mobile growth has been anemic, with an absence of new original content. All of this stuff contributed to top-line revenue growth of 5%/year, which is slightly lower than growth in global content sales. In that respect, historical performance isn’t something to write home about.

Despite modestly below-average top line growth, EA delivered CFPS CAGR’s of ~9% and 29% in the last 15 and 7 years respectively. A big part of that CFPS growth was because of the positive impact on gross margins from physical to digital distribution that impacted all the players in industry, but an equally important driver was operating leverage below the gross margin line. Exhibit N shows the difference between gross margin and adj. EBIT margin for EA since 2006, and a marked improvement took place 6 years ago, likely driven by One EA, and lower incremental development and marketing costs for in-game content sales from stuff like FIFA Ultimate Teams (our guess). Lastly, stock buybacks have just recently been eclipsing stock-based compensation, and EA’s total share count fell by 10% from 2016 to 2020, which helped support CFPS growth in excess of top line growth in recent years.

We note that from 2008 to 2011, EA recorded a number of goodwill impairments and restructuring charges, which meaningfully impacted ROE in those years. Since then, even though top-line growth has been modest, EA has started to earn an exceptional ROE, driven mainly by a combination of margin improvement and buybacks. EA’s reported ROE is now the highest in the peer group (even if we adjust for one-time items in fiscal 2020), and would be orders of magnitude larger if we adjusted for excess cash. For context, we expect EA’s ROE in 2021 to be in the low-20% range, but ROE excluding cash and short-term investments to be closer to 70%.

All told, EA’s idiosyncratic historical operating and financial report card probably deserves a B+, but industry tailwinds (margin expansion) are helping to produce an A- grade.

Financial Position

As capital allocators, the EA executive team has been relatively inactive: it’s been almost a decade since EA pursued any needle-moving M&A; they haven’t paid a dividend until recently; and, stock buybacks have been systematic and consistently less than 100% of FCF, even as they’ve ramped up in the last two years. As a result, EA’s net cash position has built quite meaningfully, both in absolute terms and proportionate to total assets. At last mark, EA was sitting on roughly $6.0 bln of net cash and short-term investments, which is quite the pocket money to be lugging about quarter after quarter. In fact, if EA took ND/EBITDA to 1.0x, they could comfortably buy back 20% of their outstanding shares at current prices, even after the Codemasters acquisition.

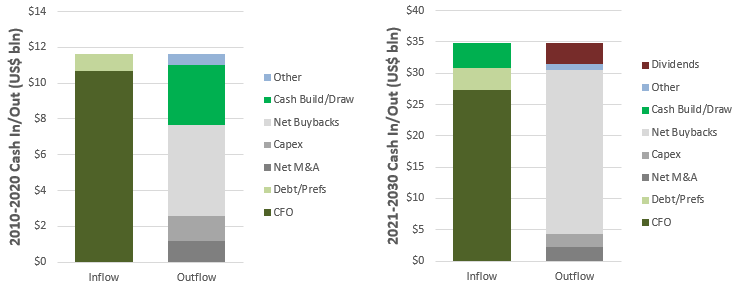

In Exhibit O we break out historical cash inflows and outflows versus our expectations under the base case. Given the pace at which EA is adding to their cash position, we think it’s inevitable that either A) they ramp up return of capital to shareholders, B) they pursue large M&A, or C) they do both. There is so much cash already within this business, and so much generated every year, that even with acquisitions like Codemasters (reflected in our model), EA will still have significant cash available for distribution.

Management & Governance

Andrew Wilson joined EA in 2000, and eventually took over as CEO in 2013. We haven’t followed EA for long, but through our research we’ve come to think about the company in pre-AW and post-AW terms. John Riccitello was Andrew’s predecessor from 2007 to 2013, and under his leadership the company pursued a lot of M&A – in fact, nearly 100% of EA’s operating cash flow was spent on acquisitions during his tenor, versus <5% of operating cash flow under Andrew. Clearly, M&A is a much smaller part of Andrew’s playbook, even though he’s wading into a small acquisition today. In any event, we appreciate that Andrew didn’t immediately pursue M&A once in the seat, and hasn’t pursued anything transformative (where the base rate for success is low).

Interestingly, Andrew grew up within EA Sports, and was once the Executive Producer for FIFA. Unsurprisingly, EA’s incremental focus over much of the last decade has therefore been on sport titles, and total sport contribution has proportionally almost doubled under Andrew. The focus on existing titles and the Ultimate Team mode has positively contributed to both gross margins and operating margins, in our view. Andrew was also clearly the pioneer, if not major contributor to, the One EA initiative, which also contributed meaningfully to margin expansion and improving ROE. It’s hard to argue that EA shareholders haven’t benefited under Andrew. At the same time, EA’s current executive team/board haven’t engaged in opportunistic buybacks or accretive M&A in the same way that we’ve seen at competitors like ATVI – and there have been opportunities to do so.

Much like ATVI, EA faced a controversial proxy season this summer when proxy advisors and CtW Investment Group recommended that shareholders vote against the say-on-pay proposal for executive compensation. Unfortunately for EA, nearly 70% of shares voted against the say-on-pay proposal. You can read for yourself CtW’s criticisms here, and EA’s stance here, but our loosely-held view is that it’s a very nuanced topic and that EA probably isn’t in the wrong in this particular case. This is obviously something we need to think about, but not a brown M&M to an investment thesis. As we look through the proxy statement, and assess other members of the executive team, we don’t find any red flags.

One final important thing we wanted to highlight was that when EA laid off 350 employees in fiscal 2019, the entire executive team decided to forego their non-equity performance bonuses for that year. Those bonuses were instead paid back into the bonus pool for all other employees. We estimate that this amounted to a ~10% haircut to total 2019 compensation for these executives, and we believe they handled this internal turbulence in a much more tactful way than ATVI when they embarked on layoffs in the same year. As a result, Glassdoor reviews and CEO Approval ratings for EA didn’t deteriorate at all, while those same ratings fell significantly at ATVI. In our view this is a signal that EA’s management cares deeply about their people, which is incredibly important for a business whose primary asset is human capital. In an interview with GameDaily.biz, Andrew Wilson made a statement that captures this sentiment perfectly:

“I don't want to try to defend things, but it's the hardest decision you make as a leader, whether you're a leader of 10 people or 10,000 people it is the hardest decision you make,” Wilson told GameDaily. “These decisions have to be made for the longevity of an organization who is moving through tremendous disruption as an industry. Any time we make these decisions we really think about it on two core vectors. One is: How can we ensure we're making decisions for the long term to position us as an organization to do what it is that we do for many years to come and deliver on the promises that we make to our players in what is a fundamentally changing, shifting world with changing, shifting requirements? And then… for anyone who is leaving the company, how do we do that in the most human way possible? How do we work with them? How do we look after them? As a company I think we do pretty good on both of those things, but again, I don't think there's anything I can say that makes it feel better for any of the people that are impacted in the process.”

Valuation & Scenarios

Revenue

We model top-line growth for EA in a similar fashion as we did for ATVI, which was largely driven by our industry growth outlook and long-term market share estimates. Exhibit P summarizes our market share forecast by platform.

The console business is obviously the most important to EA considering 70% of their revenue comes from those games. Over the last ten years EA has grown console revenue organically at more than 8%/year, and our base case forecast assumes slightly more than 6% annual growth through the next decade. As we highlighted earlier, a significant part of that growth came from higher ARPU in sports, driven by Ultimate Team contributions. It seems reasonable to expect that the runway for Ultimate Team ARPU growth is finite, and should slow in the future, particularly with loot box regulation. On the flip side, console gaming penetration in developing markets is low, and the FIFA franchise should be positioned well to capture growth in international markets. By and large, we also believe that the license agreements EA has secured result in niches that are hard for competitors to steal - including non-sport licenses like Star Wars. In select cases, like Star Wars and Apex Legends, EA has also proven they can successfully introduce new console content that takes share, and the internal Frostbite engine should help them experiment with and launch games more cost effectively than some competitors. Lastly, we think that subscription gaming services like EA Play should allow incumbents with a big catalog to take marginal share from small publishers. All told, EA has the box in some great gaming categories, has lots of breadth in their game catalog, has an internal game engine that makes development easier, and has put up some major barriers to entry for competition. They also have six years to improve on franchises like Madden and reduce the risk that they lose the exclusive license. We therefore see compelling reasons to assume that they continue to gain modest share in the base case.

We have a different outlook for the PC business, where EA has historically struggled with both distribution and new content. With the exception of Sims and Command and Conquer, it looks like EA has historically just taken console-first content and made it playable on PC (FIFA, Madden, Need4Speed, etc). Pulling content from Steam also created a serious self inflicted distribution challenge. The combination of poor distribution and lack of new content actually caused gross PC revenue to decline by 2%/year over the last decade. EA was losing market share every year. The good news is that EA has taken steps to improve the PC business. First, they reintroduced content to Steam in 2019, which helps them reach a larger audience than they have been since 2012. Second, they introduced subscription services through Steam, which should help them better monetize their game catalog to that larger audience. And third, the release of Apex Legends shows that EA can still produce new original hit games playable on PC, and introduces a new franchise with lots of potential. All of these changes helped drive PC gross revenue growth last year of 43%. EA has clearly picked the lowest hanging fruit, specifically on the distribution front, but business momentum is positive. As such, we assume revenue growth for PC content of 4%/year, which is a marked improvement over historical performance. Our revenue growth estimate still implies that EA loses modest share beyond 2021, which is rooted in our skepticism that they can continue to build successive new enduring franchises for PC.

Mobile is probably the weakest link in the story. Similar to PC, EA has largely taken console-first and PC-first content to mobile with FIFA, Madden, Sims, and Command and Conquer. Some of EA’s successful mobile-specific titles like Bejeweled where acquired (PopCap Games in 2011), and we can’t think of a single original internally developed game that’s done very well since. Gross mobile revenue has actually shrunk in recent years, while the industry has grown at a double digit CAGR. With no indication that EA can develop new mobile titles especially well, and with most of their other IP already rolled out onto mobile, we take EA’s mobile market share down by 30% over the next decade (from 100 bps to 70 bps). The result is a modest 4% CAGR in mobile revenue vs. historical growth of 10%/year and our industry forecast at 7-8%.

Lastly, EA seems to be in a worse position to capture eSports growth (ignoring Ultimate Teams) than competitors like ATVI, so we don’t expect that to be a major driver of the top-line. Apex Legends is one exception, and we assume that league ultimately generates $300 mln/year in revenue for EA.

Exhibit Q shows our aggregate top-line assumptions in the base case, which result in a 2020-2030 revenue CAGR of nearly 6% - slightly higher than historical growth of just under 5%.

Gross Margin

A greater share of distribution is done physically in the console space than PC, and given EA’s console weight, a greater portion of their overall revenue still comes from physically distributed products than other competitors like ATVI. Given our view that digital distribution will ultimately dominate all distribution, this makes the runway longer for EA to benefit from higher gross margins on digitally distributed products. In our base case we assume that revenue from physically distributed products falls from 22% of the total in 2020 to just 6% by 2030. This trend explains nearly all of our gross margin expansion expectations, as shown in Exhibit R. We are cognizant that competition for licenses could drive up royalty rates for some franchises, but believe this is a low probability outcome (revenue weighted) given the risks facing licensors and new bidders.

Operating Margin

On top of additional gross margin expansion, we expect that R&D, S&M, and G&A will all shrink as a percentage of revenue in the future. As a result, we assume operating margins expand by 5% on top of any gross margin expansion, as we’ve illustrated in Exhibit S. One driver behind this forecast is the continued benefits of scale, which history has shown to be quite meaningful. Another important reason is that we expect in-game sales growth to outpace full-game sales, and those revenue streams tend to have higher operating margins. Lastly, as EA better monetizes their catalog of games through subscription services like EA Play, we expect to see revenue growth without any meaningful increase to any of the expense lines below gross profit.

Underutilized Balance Sheet

At the end of fiscal 2Q21, EA was sitting on $6.0 bln of cash and short-term investments, with a measly $1.0 bln in debt. The company also generates somewhere close to $2.0 bln per year in operating cash flow, with negligible organic capital spending requirements. So, even after the Codemasters acquisition and the recently announced two-year $2.6 bln share repurchase program, the company will still have something like $5.0 bln of net cash at their disposal by the end of 2022. Management clearly understands that they need to distribute more of that cash to shareholders, and recently instituted a tiny dividend (~10% EPS payout) alongside the repurchase program. In our base case we assume that the dividend payout climbs to 25% and stock buybacks ramp up such that ND/EBITDA approaches 1.0x in the terminal year. The underlying assumption is that all this cash is distributed at EA’s cost of equity. If they repurchase stock below “fair value” or pursue M&A with better returns, this could represent significant upside to our base case. For reference, our model shows that EA can probably distribute more than $30 bln of cash to shareholders over the next decade versus a current market cap of ~$41 bln - and still grow the business.

The Outputs

Our base case produces net income growth of 8.5% from 2021-2030, but EPS growth closer to 14% because of buybacks. Our estimate of fair value in that scenario is ~$185-190/share, which is 30-35% higher than the current share price. Exhibit T shows a snapshot of our DCF, and the full model can be found at the top of this post.

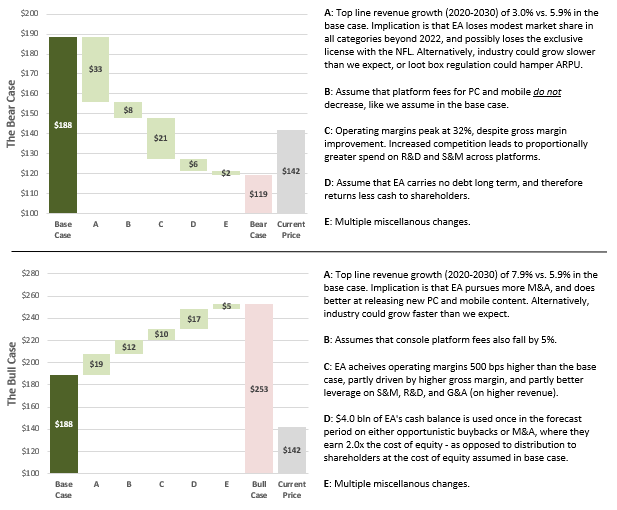

As always, we ran two additional scenarios, meant to represent the 10% and 90% outcomes in a probability distribution (the bear and the bull). Exhibit U shows how we arrive at each scenario, using the base case as a starting point.

Lastly, we visualize our scenarios versus the current price in a magically normal distribution (Exhibit V). It’s clear that we believe risk is skewed meaningfully to the upside for the incremental EA investor today, which begs the question, where do we have a differentiated view from the market?

To answer that question, we adjusted some of the KPIs in our DCF to arrive at the current share price. Two combinations include:

Revenue growth of 5.0% (100 bps lower than our base case), and no operating margin expansion from 2021 onward. Basically any gross margin expansion is completely offset by proportionally higher R&D, S&M, and G&A, despite the fact that these expense lines have only fallen (proportionally) over time. EA’s global content market share would also fall from 16% to 15%.

Revenue growth of 3.4% (260 bps lower than our base case), and operating margin expansion that’s equal to gross margin expansion. Said differently, no future benefits from proportionally lower R&D, S&M, or G&A. Gross margin expansion is a very low risk expectation given the obvious shift from physical to digital, so this still seems punitive. The implication is also that EA’s global content market share falls from 16% to 12% (historical low was 15%). Loot box regulation would have to knee-cap Ultimate Teams in a way that was hard to recover from.

By toggling these assumptions and reading other research, it seems likely that our differentiated view is partially rooted in higher operating margin expansion than the market expects. In addition, the market is probably more concerned about the sport category and EA’s ability to produce new content (or protect Ultimate Teams) than we are. Either way, our research makes us comfortable taking the “over” on current expectations for both top-line growth and margins.

Lastly, we tend to shy away from heuristics, but sometimes find them to be a useful gut-check. In this instance, if we strip out cash, EA looks to be trading at 20-21x fiscal 2022 P/E. Put differently, they’re trading at a 5% earnings yield, can grow EPS by 2.5-3.0%/year just from realizing margin expansion (no capital), and grow revenue by some mid-single-digit growth rate without any meaningful capex (most of thir growth capital is expensed and already reflected in EPS). All this from a business with incredibly strong moats around many of their existing franchises. We don’t often stumble across this kind of setup.

What would the 10th Man say

Insurmountable loot box regulation in all big markets.

The second easy starting point would be a criticism of our margin expansion assumptions - certainly, if we turn out to be wrong, we’d expect that to be the reason. If the sport category does prove challenged, then it’s reasonable to expect that EA might focus more effort on creating new titles in other categories, which could result in much higher R&D and S&M. Alternatively, we could be underestimating the benefits of scale, One EA, and subscription services.

Which brings us to the third point. The sport category could lose share globally (MAU and/or ARPU), which would bring down our revenue growth assumptions, but might also drive EA to do a big acquisition which comes with a suite of risks. If an acquisition works out poorly, it could be meaningfully dilutive, and EA circa 2013 has proven that this is possible. If revenue growth in the sport category slows, and EA’s returns are still quite high, the licensors (like FIFA) might demand higher royalty rates, which would eat into gross margins as well.

Lastly, from the bear perspective, while One EA seems to have been successful to-date, one risk is that EA underinvests in content by adopting too strict of a cost-conscious stance. This creates some terminal value risk, particularly if they lose some highly coveted licenses as a result.

We could also be totally wrong about the upside. In a blue sky scenario where Frostbite becomes a great platform for external mobile developers, EA might take meaningful share in the mobile market as they grow their partner network. If EA’s global mobile market share went from 1% today to just 2% in 2030, it would add $30/share to our estimate of fair value. We don’t even reflect that in our bull case. Our push back would be that Unity seems to absolutely dominate mobile, and we see no evidence so far to suggest that EA can displace them. Nevertheless, if we’re spectacularly wrong about the upside, we suspect it would be because our mobile assumptions were wrong.