We aren’t Macaulay-Culkin-old, but our peak reaction time is clearly in the rear-view mirror, and we routinely get smoked in fast-twitch games like Call of Duty. Nevertheless, we consider ourselves avid life-long console gamers, and that passion - if we can call it that - led us into a deep-dive on the video game industry. Research what you love and you won’t work a day in your life… or something like that… right?

In this series, we focus on the three big publishers ( ATVI 0.00%↑, EA 0.00%↑, TTWO 0.00%↑), but we might build on it over time as we look at other companies in the space like Unity and Roblox. Part 1 of the series explores the major themes that impact top-line growth and margins for publishers, while subsequent posts delve into the idiosyncrasies of each. Many of these views reflect the learnings and prognostications from experts in the gaming industry, and we try our best to credit those individuals where credit is due. We still consider ourselves relative novices in the space, so please reach out with criticisms and suggestions if you disagree with any of our analysis at the10thmanbb@gmail.com. To aid in that feedback process, we continue to provide all of our models and industry analysis (company models to follow in subsequent posts, but our industry model can be found above).

***NOTE: If we had to grade the data quality of most of the macro data we lean on in this series, we’d probably give it a “B” or “B-”. There are only a handful of industry sources (like Newzoo, NPD, and VGChartz), and they often have conflicting figures or a long list of caveats. Where possible, we try to corroborate macro data with findings from our bottom-up research, but nevertheless believe that the confidence intervals on some of these estimates/forecasts is slightly wider than normal. In English: cut us some slack if we quote some figure to be $100, but you actually believe it’s $110 - the important thing is often just directional trends.

Industry Map

Before we begin, it’s helpful to understand where the publishers fit in the value chain, so we’ve created an industry map to do just that (Exhibit A).

The value chain is interesting because some layers are very fragmented, like game development and physical distribution, while others are effectively oligopolies, like digital distribution and console hardware. The publishing space is somewhere in-between, with less than ten major competitors. A few companies, like Microsoft, are vertically integrated and seem to have their hand in every piece of the pie. But, the publishers we’re looking at play no role in distribution, online services, or hardware – for them, it’s all about creating great content and monetizing it through unit sales, in-game transactions, and – to a much lesser extent – eSports.

Industry Themes & Outlook

There are a surprising number of themes that are changing the video game landscape. We’ve done our best to discuss how each theme has played out so far, and how we expect it to play out in the future. We provide a brief summary below before diving in.

Theme #1: Mobile and Casual Gaming

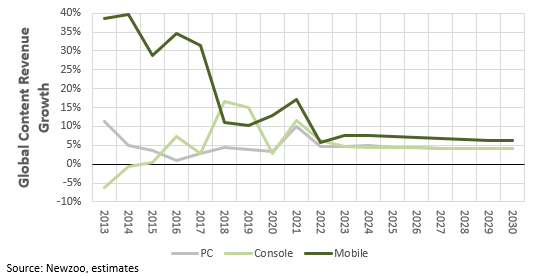

Newzoo data (Exhibit B) shows global game market revenue by device, and while the global market has grown at +11%/year from 2012 to 2019, there is clearly a bifurcation between mobile revenue and everything else; both PC and console revenue has grown at slightly less than 5%/year, while mobile is up 27%/year. The clear driver behind the rise in mobile gaming is increasing smartphone penetration; in the United States, it went from ~35% in 2012 to more than 80% by 2019. In fact, nearly half of the global population now owns a smartphone, which makes for a massive market of potential mobile gamers; and, unlike PC and console, where hardware costs are quite high, the incremental hardware cost for mobile gaming is effectively nil. As a result, Newzoo data suggests that there are about 730 mln console gamers, 1.3 bln PC gamers, and a whopping 2.6 bln mobile gamers! We expect that the number of mobile gamers will continue to grow faster than PC and console gamers as A) global smartphone penetration increases, and B) more of those smartphone owners become casual gamers. It’s also possible that mobile gaming is the “gateway drug” to console and PC gaming, and could drive some user growth in those markets as well.

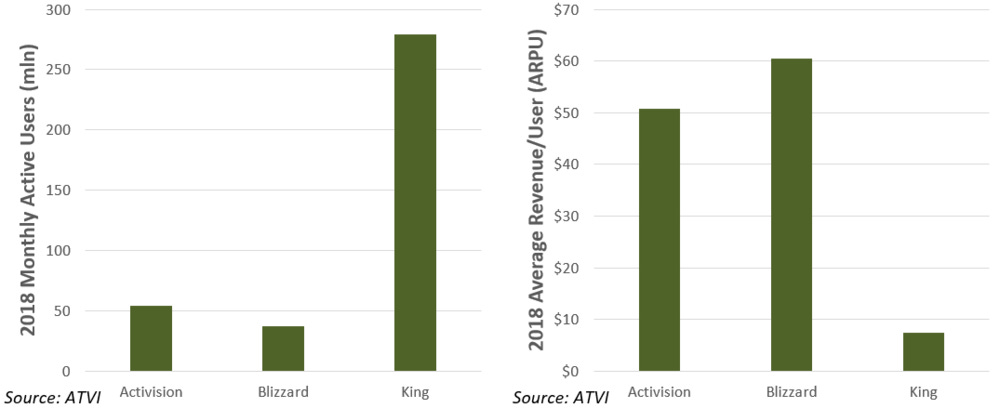

The mobile gaming experience is clearly a casual one. You don’t sit on the edge of your seat, in front of a large screen, yelling over a headset for two hours at a time. As a result, casual gaming tends to be harder to monetize than most PC or console games. ATVI conveniently reports monthly active users and revenue per segment, and we can see that King (the mobile division) has >6.0x the user base of PC (Blizzard) and console (Activision) divisions, but an ARPU that’s 85% lower than those other businesses (Exhibit C).

We can also see that mobile gaming monetization is probably improving, with mobile ARPU growth for companies like ATVI of more than 100% over the last four years, and data from Newzoo suggesting global ARPU growth of ~60% over the same period. Most mobile games are free-to-play, at least initially, and a very small percentage of total players are monetized through in-game transactions. Through our conversations with major publishers, it’s clear that <10% of total mobile players are monetized, and that a small cohort of “super payers” account for the bulk of total revenue. Clearly, most of the large publishers are going through an experimentation phase to figure out how to A) monetize more players, and B) extract more per existing payer. We expect that mobile ARPU continues to grow as publishers improve on that trial and error process, particularly as some of the most successful console and PC intellectual property (IP) is rolled out on mobile like Diablo Immortal (ATVI in partnership with NetEase).

Lastly, we find it really interesting that a significant portion of mobile games are developed by, or in partnership with, companies like Tencent and NetEase. Tencent owns the majority of Riot Games, a significant stake in Epic Games, and has partnered to develop major titles like Call of Duty Mobile (ATVI) and PUBG Mobile (PUBG Corp). They also partnered with EA to create a mobile version of Apex Legends. The large western publishing companies are clearly late to the “game” in mobile, and Exhibit D shows how much lower their mobile market share is than in the console and PC markets.

The large western publishing companies have tried to grow their own mobile divisions in the last 4-5 years, but despite these efforts, their share of the market remains small. In time, as internal mobile teams get better, and existing console/PC IP is rolled out on mobile, we expect to see their mobile share grow, and more of those mobile titles to be launched without partners. For example, ATVI released Call of Duty Mobile in late-2019, which has been downloaded more than 250 mln times, and was a natural extension of existing console/PC content (although they still used Tencent). This was certainly more successful than a brand new mobile franchise would have been coming out of ATVI.

Theme #2: Free-to-Play Games & Evolving Monetization Strategies

As far as we can tell, the free-to-play (F2P) model for PC and console has been around for a very long time. Successful F2P games like League of Legends have been around for more than a decade, but the model seemed to really become mainstream when Fortnite launched in 2017. Over the last three years, Fortnite has logged more than 350 mln players and generated revenue from in-game purchases of nearly US$6.0 bln (US$15/player). If we use a mid-point of monthly active user (MAU) estimates, Fortnite has generated north of US$40/MAU to-date, which is much higher than we would have expected prior to this research. Following Fortnite’s success, EA launched Apex Legends and ATVI launched Call of Duty: Warzone, both of which mimicked the battle royale style that Fortnite made popular. When we look at Twitch viewership, these F2P games routinely show up as the most popular.

There is also a hybrid F2P model, whereby a paid game releases additional free content to keep players engaged for years following a game release. GTA V is a good example, where players need to purchase the GTA V game, but get perpetual access to GTA Online, which has been releasing free new content for 7 years. Under that model, players can choose to purchase things like penthouse suites or helicopters, and most of them do, which easily covers the cost of the free content.

In our mind, there are three ways that F2P games end up monetizing:

In-game purchases (MTX/DLC): some of the first iterations of in-game sales revolved around a pay-to-play or pay-to-win philosophy, but that approach has largely been discarded for most genres. Today, more games monetize by selling cosmetic items in microtransactions (MTX) that don’t impact multiplayer gameplay, like skins in Warzone or Nike Air Jordan’s in Fortnite. In many instances, F2P games also sell new downloadable content (DLC; missions/maps/modes). MTX/DLC is the largest and most directly visible monetization approach today at the large publishers.

Upsell to paid games: after the Warzone release, ATVI noted that Modern Warfare game sales saw a record increase outside of a CoD launch quarter as new Warzone players upgraded to the paid game. Not all franchises have that dual F2P/paid-game offering, but for those that do, this is a clear driver behind the F2P development decision. The few data points we’ve seen suggest that most F2P games end up being additive to publisher revenue rather than cannibalizing, particularly when the dual offer exists.

eSports: this is still nascent, but there are ways to monetize successful F2P games with high streaming viewership through eSport leagues. F2P games have the potential to attract much larger audiences than that of traditional paid games, which provides for a better starting point when launching a league. We’ll touch on this more in the next theme.

These monetization approaches, specifically MTX/DLC, have also spilled over into traditional paid games like FIFA. EA has a game mode called Ultimate Team embedded within its sports titles, which are online competitive leagues. Users build their own team and compete in online events, but to build the best team typically requires that users purchase player “packs”. It’s the embodiment of pay-to-win gaming, and although there are loads of criticisms levied at EA, it’s still an incredibly profitable and growing game mode.

The growth of in-game content revenue (MTX/DLC) at all of the publishers has been extraordinary. Exhibit E shows that these sales have grown proportionally over time (some guesswork required), with 40-50% of total revenue coming from in-game purchases last year. Importantly, we haven’t noticed any negative impact to top line revenue growth from the shift to F2P and in-game monetization – if anything, it’s been additive.

As we understand it, the incremental development cost to release new in-game content is pretty low, and operating margins on this revenue are higher than operating margins on digitally (or physically) purchased games. As such, a portion of the historical operating margin expansion at PC and console businesses is likely attributable to the growth of in-game content revenue. We expect that operating margins at the publishers will continue to benefit from this shift over the next decade.

F2P games, particularly for PC, have no real barriers to entry for people that don’t game today; as a result, more people likely experiment with video games, and some of those gamers might get converted to more serious paying users. Just like mobile gaming might be the gateway drug to console and PC gaming, we suspect F2P might be the gateway drug to hardcore gaming (higher ARPU users).

To summarize, F2P gaming and the evolving monetization mechanisms seem to have been positive for the publishers: we don’t see any evidence of revenue cannibalization as F2P gains popularity; we expect that in-game sales will grow proportionally faster than full game sales, and should continue to support an operating margin expansion narrative; and, to the extent that F2P converts casual gamers to hardcore gamers, ARPU for the PC and console industry could also increase.

Theme #3: eSports & Streaming

We would have laughed out loud if someone told us in 2010 that a few million people would concurrently tune in to watch a bunch of gamers compete in a video game tournament within the decade. But here we are. The 2019 League of Legends World Championship event had peak viewership of nearly 4.0 million people, and average viewership throughout the month-long event of over 1.0 million. To put this in context, the NHL enjoys average viewership per game of roughly 5.0 million during the final Stanley Cup series.

Twitch, which is now the largest video game streaming business in the world, was launched in 2011 and purchased by Amazon in 2014 for a baffling $970 mln. The average concurrent viewers on Twitch has increased by 15x since Amazon’s purchase, and now sits north of 2.0 mln. Think about that for a second. That’s the average concurrent viewers for any time of day - 24/7/365. Viewership troughs at about 1.0 mln in the morning and peaks above 3.0 mln at night. Exhibit F illustrates this trend nicely. Clearly there is growing consumer demand for video game streaming, even if we adjust for the COVID impact.

Just like traditional sports and media, video games can be monetized by selling broadcasting/streaming rights. In 2016, ATVI sold the exclusive streaming rights for the Overwatch League to Twitch for $45 mln/year for two years. When that contract expired, YouTube agreed to pay a reported $54 mln/year for three years for the exclusive streaming rights to the Overwatch League and the new Call of Duty League. Returning to the NHL for context, NBC paid $200 mln/year for a ten-year broadcasting deal in the United States. As viewership increases on these streaming platforms, we’d expect the value of streaming rights to increase, but clearly have a way to go before they are anywhere near traditional sport deals. We also expect the number of deals to grow as new leagues and games are created, but plateau at some saturation point, just like traditional sports have.

Publishers can also sell team rights like ATVI did with Overwatch and Call of Duty. When Overwatch launched in 2017, ATVI sold 12 teams at ~$20 mln a pop. They have since expanded the league to 20 teams. The Call of Duty League also started with 12 teams in early-2020, and team owners reportedly paid $25 mln per team – 25% more than Overwatch. Team sales aren’t significant revenue streams for publishers, particularly considering they are one time in nature, but the figures do show that a wide range of investors clearly see value in an eSports franchise. In case you aren’t convinced, Robert Kraft, the owner of the New England Patriots, purchased one of the first Overwatch teams. Who would have guessed…. football and video games!?

In addition to broadcasting rights and team sales, most eSport leagues generate significant revenue from sponsorships – again, similar to traditional sports. As popularity of the leagues increases, we also expect sponsorship revenue to grow. The sponsorship lineup for League of Legends already includes some heavy hitters like Mercedes-Benz, Spotify, MasterCard, State Farm, Bose, and AXE.

The publishers we’ve talked with that operate eSport leagues today tell us that revenue from team sales, broadcasting rights, and sponsorships hardly cover the cost of operating the leagues. These are very small profit contributors. But, we do expect that to change over the next 10 years, with the most successful leagues likely to generate hundreds of millions of dollars in direct profits, but also to drive higher unit sales and in-game content revenue as franchise popularity grows.

Lastly, we note that there is probably some advantage to being one of the first big leagues, specifically because of fan loyalty. Most kids that grew up playing hockey or football exclusively end up being hockey and football fans. Rarely do those life-long hockey fans attach themselves to a new sport like baseball. You learn how to play, find friends who play, and attach some part of your identity to the sport. eSports might be a little different, but we suspect many of the same dynamics are at play, making it important to build an engaged fan base while the playing field is relatively sparse. To varying degrees, ATVI, EA, and TTWO are all positioned to benefit from growth in eSports.

Theme #4: The Shift from Physical to Digital Distribution

If you wanted to buy a video game in 2005, you’d have gone down to Walmart, GameStop, or something of the like, and purchased a physical disc. Since then, improvements in payment technology, internet connectivity and bandwidth, and other digital infrastructure, has improved sufficiently to enable direct digital downloads for both console and PC games. Today, the majority of video games are purchased without the consumer ever having stepped foot in a physical store. Ignoring digital in-game revenue, it appears that 80-85% of PC games are sold digitally, and roughly 50-55% of console games. One of the large publishers tells us that the shift to digital for PC games is slowing down (but still growing), while console continues to see about a 5% shift from physical to digital each year.

Why does this matter? The primary reason is that gross margins on digitally distributed products are much higher than the gross margins on physically distributed products. Exhibit G shows the cost of revenue breakdown by distribution method. This is one of the important explanatory variables for why gross margin expansion has occurred at video game publishers over the last decade. On top of the fact that unit sales have become increasingly digital, we note that all microtransactions (MTX) are obviously digital, and therefore also drive higher margins. We ultimately expect that 90-95% of all revenue for publishers will come from digital channels, which should continue to drive modest gross margin expansion over the next decade.

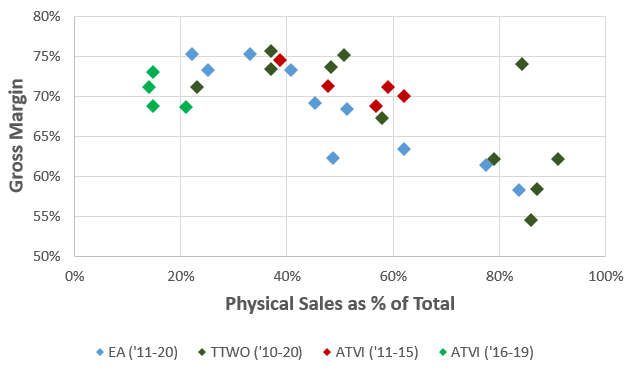

Exhibit H shows the historical relationship between gross margins and physical sales as a percentage of total sales, and the average r-squared from each of the linear regressions is in the 70% range. The outputs from our linear regressions suggest that terminal gross margins, with 95% of revenue from digital channels, should be in the 81-82% range, all else equal. In other words, gross margins can probably expand by another 5%+ for each of these businesses.

Theme #5: Digital Platform Fees

For nearly 15 years, Valve had a functional monopoly on digital distribution for PC games through Steam. We estimate that their market share peaked at 75-85%. Some of the big publishers have their own distribution platforms, like EA with Origin or ATVI with Battle.net, but they are minnows compared to Valve’s great white shark. As a result, Steam had significant market power and was able to charge a 30% take-rate on digitally distributed games. But then Epic Games launched the Epic Games Store (EGS) in 2018 to compete with Steam, and they charged just 12%, which put the Steam take-rate under pressure. Right when EGS was launched, Steam amended their revenue sharing agreement such that games with annual revenue between $10 and $50 mln paid 25%, and games with revenue in excess of $50 mln paid just 20%. This competition transferred more dollars back into the pockets of publishers, and we wouldn’t be surprised to see continued pressure on the Steam take-rate given how much lower EGS still is. This should be a modest tailwind for the publishers. Every 1% reduction in the platform take-rate would work out to a ~2% increase in gross profit for PC games.

We also note that many of the publishers operate their own digital distribution platform, which allows them to go directly to the consumer (DTC) and avoid the platform fee altogether. That said, the Steam community is massive and connected in ways that those other platforms haven’t been able to replicate. In 2012/13, EA decided to sell most of their PC content exclusively through Origin, and pulled content from Steam. Net revenue fell consistently for the seven years following that decision. In fiscal 2019, EA decided to reintroduce content to Steam, and net revenue increased by 30% (and that accounts for the platform fee) in the year following. The decision to reintroduce content was at least partially because of the lower platform fees, but it’s clear to us that the value of Steam as a distribution channel is far greater than the platform fee they charge (even if it stayed at 30%). As such, we expect that DTC penetration will remain modest for PC games, particularly if platform fees keep falling.

In the PC market, the range of hardware SKUs is massive and that hardware is sold independently of the digital distributors. In the console market, this isn’t the case: Microsoft owns both Xbox and the Microsoft Store, Sony owns PlayStation and the PlayStation Store, and Nintendo owns their hardware and the Nintendo eShop. If you want to buy a digital version of Call of Duty for Xbox, you buy it from the Microsoft Store – full stop. As a result, there is no competitor like Epic Games to help drive down take rates, and the digital distributors for console games can continue to enjoy a 30% take-rate on game sales and microtransactions. Cloud gaming platforms like Stadia introduce some competition to console gaming, but we don’t think it’s sufficient to result in a reduction of platform fees for the incumbents. Matthew Ball has explained the near-term limitations of cloud gaming well in this blog post and his interview on Invest Like the Best. To summarize what we view as the primary hurdle: latency is a major problem for any fast-twitch multiplayer game, which happens to be most AAA games. In other words, “you’re competing against the speed of light”. Matthew holds the view that a new genre of games will be created by cloud gaming, but that’s many years away and we don’t think it’s totally relevant to the big publishers today. To summarize, unlike PC gaming, we don’t expect platform fees to fall for digitally distributed console games any time soon.

Lastly, the mobile gaming ecosystem is similar to console in that two incumbents dominate the smartphone operating software market, and therefore also dominate the digital distribution of content through their respective stores. Both Apple and Google charge 30% for games and transactions through their app stores, similar to console take-rates. We don’t have any firm views about mobile take-rates, but the continuous complaints of app store developers like Epic, Netflix, Match, and Spotify, highlight that the developer community is clearly peeved with app store fees. Epic recently went to metaphorical war with Apple when they violated the app store rules and subsequently released this epic (pun-intended) satirical video. As a result, a legal battle is now underway between Epic and Apple. It’s not inconceivable that Apple and Google willingly reduce take-rates or get regulated in such a way that the take-rate on mobile games falls in the future – at the very least, risk is probably modestly skewed to the downside for platform fees, which is good for publishers.

With the exception of Steam, we don’t expect major changes to fees for digital content distribution in the base case, but we clearly suspect that the risk on those fees is skewed lower, and we reflect that view to varying degrees in our forecasts and valuation of the publishers.

Theme #6: Social Gaming

The quintessential gamer in the 1990’s would probably be described as a hardcore 15-to-30-year-old male, with few friends, sitting in his parent’s basement for hours on end, rarely seeing the light of day. At least, that’s how they used to be described in pop culture – like Cartman in Make Love, Not Warcraft. But that perception has changed a lot as video games have become more mainstream, with billions of people playing games from both genders, all age categories, and lots of diverse backgrounds. More importantly, the video game experience has become more social as massive online multiplayer games gain popularity. The shift toward social gaming is interesting because it increases the value of games to users, but more importantly, it widens the moat around the largest gaming franchises.

For anyone that’s read Ready Player One or Snow Crash, you likely understand what the social experience looks like if digital interaction is taken to the extreme in something like the metaverse. There is nothing that comes even remotely close to those ideas today, but some of the metaverse features are becoming more prevalent in the online multiplayer video games du jour. We once again lean on Matthew Ball’s work as we think about this (link). Here are some examples:

Cross-platform play is more common, where players can engage with each other regardless of the decision to play on PC, Xbox, PlayStation, or Stadia. Ten years ago, Xbox players played with other Xbox players, and PC players played with only other PC players.

The number of concurrent participants in a game is increasing, and the size of the digital space is growing. Games like Fortnite and Warzone can have 150-200 players engaged simultaneously in a massive open world map.

More games allow players to create unique identities by purchasing custom avatars and other items. In some instances, there are even secondary markets for these digital goods (link). Just like the real world, no one really enjoys homogeneity, and differentiated appearances contribute to your identity.

Increasingly, people can engage with a gaming community without actually participating in the game, specifically through streaming services. Just like the real world, millions of people enjoy watching soccer, but don’t play (or don’t play competitively). The viewing experience itself can become a social activity, and has implications for the real-world economy through the sale of physical items and live events. Companies like 100 Thieves operate dozens of eSport teams, and sell physical branded merchandise. All of this stuff contributes to an identity that sits in both the physical and digital worlds.

Companies like Roblox also allow users to create content, which massively increases engagement, and is a critical step toward creating a digital economy.

All of this stuff contributes to the formation of communities, and communities create loyal fans and players. That loyalty creates a real switching cost for a member of that community. If a Call of Duty player has a favorite Call of Duty streamer, a group of friends that they play with online, and has spent money customizing their online identify, it’s unlikely that they decide to all of a sudden change gears and commit to Overwatch or Battlefield. In their latest annual report, ATVI shares an example of this social gaming theme:

“We recently received a heartfelt letter from a Call of Duty fan in Ireland. He wrote to us explaining how he and three schoolfriends had stayed in close contact by playing Call of Duty even as they went to university, got jobs and moved around the world. He talked of the bond that they forged over many hours of gameplay over many years, and how in turn his mother would see the enjoyment and warmth that he felt from spending time online with his close friends. When his mother was tragically killed in March this year, those friends traveled long distances to be by his side and comfort him, making him forever appreciative of the strength of the friendships forged through years of enjoying Call of Duty together. They remain in touch through the social experience of playing Call of Duty.

Stories like this are a powerful reminder of how our titles can impact, inspire and unite people around the world, empowering them to achieve amazing things through their shared love of gaming. Although we have only just started to scratch the surface of what’s possible for social networking around our games, we are already connecting people around the world in extraordinary ways. We are committed to exploring innovative ways to bring our players closer together, further deepening the experience for communities and in turn widening the moats around our largest franchises.”

We also found some research to support the idea that social gaming increases engagement (here, here, and here). Each study used self-reported data, which seems to have its drawbacks, but the conclusions are still interesting. Notably, the studies seem to find that multiplayer video games have a positive impact on self-esteem and social relationships, and that there was a positive relationship between number of social connections in a game and hours played.

All told, we agree with ATVI that the increasingly social aspect of gaming contributes to wider moats for large existing franchises. As that happens, the repeat customer acquisition cost, for existing players that go on to purchase the next iteration of a game, probably falls. It might also lead to higher ARPU for a given title. Both of these things should positively impact net profits. On the flipside, it would also make it more difficult for a publisher to launch a brand new game and take share from a successful competitor’s franchise. We expect that the net result will be lower variability in market share, but slightly more profitable businesses over time.

Theme #7: Rising Game Development Costs, Third-Party Engines, and Price Increases

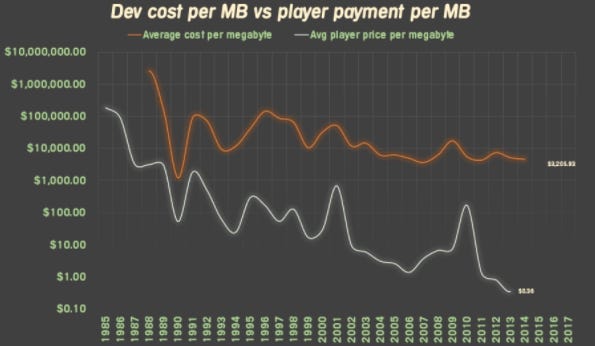

Raph Koster wrote an awesome piece for VentureBeat in 2018 on the rising cost of game development (link). He uses a sample of 250 games from 1985 to 2017, using private data from his industry contacts – we haven’t seen anything else this detailed in our research. He shows that the number of bytes per AAA game has increased at a mind-boggling rate. As gaming hardware improves, games can become more complex and support better graphics, which means the software running the games becomes increasingly sophisticated (more bytes). Raph shows that even though the game development cost/byte has fallen, the total cost of game development is still increasing at an exponential rate (~10x every 10 years). There are still indie games that get developed on the cheap, but his data showed that the average cost to develop a AAA game was ~$90 mln in 2017, up from $10 mln (2017 dollars) in the early 2000’s (Exhibit I). As development costs increase, the barriers to entry for new developers increases, all else equal.

The other great illustration worth highlighting is shown in Exhibit J. He plots game development cost/megabyte vs. the player price/megabyte, and the slope of the two lines indicates that margins are compressing (price falls more than development costs), all else equal. In real dollars, the price of a game has fallen by roughly 50% from 1990, despite the increase in development costs! So not only is the hurdle to develop a game increasing, but expected margins are falling. This makes it really hard for 10 people to start an independent developer and succeed. This is a good thing for the incumbents.

We chatted with someone that worked on game development at ATVI, and he told us that the biggest cost of game development is all the software engineers and designers required to write code and design the game mechanics (ie. how weapons work, how the wind blows, etc). To write all that code and think about all those game mechanics from scratch is an arduous process. And that’s where the game engine steps in, which modularizes common building blocks to speed up the development process.

Most of the big publishers have their own internally developed game engines. EA has one core engine called Frostbite that runs most of their games, while ATVI and TTWO have multiple purpose-built engines for different franchises, internal development teams, and game types. For example, Call of Duty has a purpose-built engine that’s built around the needs of the Call of Duty franchise, and is one reason that ATVI can release a new Call of Duty title every single year (faster/cheaper than writing all that code from scratch).

The cost of a game engine for AAA games, particularly one that’s purpose built or all encompassing, can be tens, if not hundreds of millions of dollars, particularly in recent years. This is a clear barrier to entry for independent game developers that lack the deep pockets of the big publishers. In steps the third-party engine market, which seems to be dominated by two companies: Epic, which built Unreal; and Unity, which created an engine in their name. Matthew Ball describes third-party game engines better than we could, so we refer you there for a more in-depth look at both platforms (link). As we understand it, Unreal and Unity socialize the game engine cost among a huge base of users. The Unity prospectus shows that they spent $450 mln on R&D over the last two years, and are spreading that cost out over 500+ large customers. Even the big publishers have been using third-party engines as they get better, particularly for mobile. In our view, these ever-improving third-party engines should help reduce development costs, or at the very least, keep a lid on them. Two potential consequences of ever-improving third-party engines is that it might either A) impact market share of incumbents, or B) prevent price inflation of content. We don’t really see any evidence of this so far, but it’s probably something worth tracking as a potential investor in the space.

As we’ve already touched on, one reason for rising software development costs is improvements in hardware. When a new generation of consoles are rolled out, all the assets in a game need to be produced at a higher level of quality (e.g. more pixels). It also allows for bigger games. Apparently, this was a big deal with the switch from PS2 to PS3, but less so in the next transition. We talked to a developer that said most assets on current generation consoles are already produced at a super high level of detail and then downscaled, so the transition to the upcoming generation in the next 1-2 years shouldn’t necessarily result in much higher development costs. Nevertheless, big publishers have already started raising prices for the first time in nearly 15 years: TTWO is going to charge $70 for NBA 2K21, and ATVI will charge $70 for Call of Duty: Black Ops Cold War. That’s a 17% price increase. The reason cited by both companies is rising development costs, but also better value per game. We suspect that the price elasticity of demand for popular AAA content (high brand value) is much closer to 0.0 than -1.0 (so relatively inelastic), although we haven’t been able to find data to prove or disprove this hypothesis. If we’re right, then we should expect to see a small revenue step change and modest margin expansion as some games are rolled out at the $70 price point.

All told, despite some great third-party engine offerings, it does feel like barriers to entry for game development are rising, which creates some modest scale advantages for large publishers. This probably acts as a modest tailwind for net profit, particularly as some pricing creeps higher in the near-term.

Theme #8: Subscription Game Offerings

An important pillar in the console manufacturer strategy is to secure exclusive content for that device. If users want to play Halo, for example, they need to own an Xbox. That’s one reason that the console manufacturers have their own development studios. The historical distribution model was to sell individual games as stand-alone products, but more recently the console owners have introduced subscription offerings. Microsoft’s Xbox Game Pass seems to be the best iteration of this, which already had a number of awesome titles like Halo, Gears of War, Minecraft, and The Outer Worlds, and will soon be adding popular titles like Fallout and The Elder Scrolls following the acquisition of Bethesda.

The subscription game offering is basically just a bundling of an unbundled service. The Xbox Game Pass charges users $145/year for unlimited access to 100+ titles (and growing every month). To figure out whether or not that’s a good deal, we looked at Newzoo data to see that global console ARPU is somewhere in the $60-65/year range, but U.S. ARPU is probably $175-200/year. Of that $175-200, we estimate about ~$100 is game purchases, and the rest is in-game content sales. That’s the equivalent of 1.5 game purchase per year. So, the Xbox Game Pass is the equivalent of players increasing their game purchases by about 50% in a year, but those players get access to a huge library of content for a relatively low marginal cost. If you were already a consumer that played Halo, this offer probably makes sense. If you play a game like CoD, that isn’t included in the subscription, then you probably don’t get “upsold” into the bundle. At current pricing, we don’t think Game Pass takes share from the big publishers, but this is a key risk to monitor.

We were initially concerned that a shift to subscription game offerings would have a deflationary impact on content pricing from third-party publishers, but closer inspection leads us to believe that shouldn’t be the case anytime soon. Companies like EA have actually partnered with Microsoft to offer EA Play (their own subscription service) to Game Pass users, for an incremental cost of $30-60/year. EA Play doesn’t include new-releases, but does let users play 10 hours of new-release games for free before a purchase decision is required. In-game transactions also accrue to EA, not Microsoft. Exhibit K shows how revenue for EA might change depending on how many existing EA players convert to EA Play, and the percentage of those converted EA Play subs that still buy new-release games. We assume that total MAU increases by 10% (exclusively through EA Play), and that ARPU for converted subs that still buy new-release games is 25% lower than before they converted. Probabilistically, the introduction of subscription offerings likely ends up being positive or neutral for the publishers, so long as the subscription offering doesn’t include new-release games. Despite our growing comfort that bundling won’t be value destructive, it remains a difficult-to-predict risk when valuing the publishers - it’s a known unknown for us.

Google and Amazon both have cloud-gaming platforms with subscription offerings. Google’s Stadia has been around for a couple years, and doesn’t appear to have been overly successful, while Amazon is in the midst’s of launching Luna, so we have very little data to assess. As far as we can tell, neither subscription offering has exclusive content – in fact, both providers lean on third-parties for content like TTWO and Ubisoft. The subscription offerings are slightly different than the subscription offering of the console owners like Microsoft, in that the subscription fee effectively replaces the up-front hardware cost of a console/PC, and most good content still needs to be purchased. In the Luna example, there are two subscription choices – Luna+ and the Ubisoft upgrade, which is likely going to be monetized similar to EA Play. On top of the fact that cloud gaming probably isn’t ideal for fast-twitch multiplayer games, the lack of exclusive content probably prevents them from gaining huge share or impacting pricing in the medium term. We aren’t as worried about this as some of the other topics discussed above.

As an aside, Amazon Game Studios spent roughly 5 years and tens of millions of dollars to launch a AAA game called Crucible in May of 2020. This was a F2P third-person shooter, and presumably Amazon’s strategy was to build out its own exclusive content that could be available on Luna+. But, a few months after launch, Amazon sent Crucible back into closed beta, and then eventually cancelled the game (link). Apparently, they’ve also faced a number of delays for other games in development. Crucible’s lack of success, and the challenges Amazon seems to be facing in game development, are great examples of how hard it is to successfully launch AAA games. This is also why the Microsoft acquisition of Bethesda was so interesting, because even though Microsoft has its own development studios, they chose to buy additional content. They clearly agree that AAA IP is difficult to build from scratch. That’s good news for the incumbent publishers, because it means that balance of power between content owners and hardware/cloud businesses clearly sits with the content owners. This makes us less concerned about the potential threat of subscription game offerings.

To summarize, the introduction of subscription services is a key risk we need to monitor for the publishers, but we haven’t found sufficient evidence to suggest that this will be a meaningful net-negative for publisher profitability, particularly in the base case.

Theme #9: Demographic Shift

In our view, media consumption habits are typically formed at a pretty young age, and can be sticky over time, specifically for interactive media. If you didn’t grow up with video games, it’s unlikely that you’d just pick up Halo in retirement. Conversely, if you grew up playing video games, you’re much more likely to continue playing later in life.

The first coin-operated video arcade game, Computer Space, was introduced in 1971 - nearly 50 years ago! Nintendo released their first console in 1983 (37 years ago), Sony released the first PlayStation in 1994 (26 years ago), and Microsoft introduced the first Xbox in 2001 (19 years ago). Somebody who is 50 years old today would have probably dabbled with video arcade games, but would have been in their mid-20’s when the first PlayStation was released - they were unlikely to become a video game enthusiast. On the flip-side, someone who is 25 years old today would have absolutely grown up in an era of serious console gaming, and is much more likely to 1) have played console/PC video games as a kid, 2) still enjoy playing video games today, and 3) continue gaming as they enter their 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s than people that age today.

We recognize that it’s difficult to guess how video game consumption for a given age cohort might change as gamers age, but directionally we feel strongly that gamer penetration in older cohorts will be much higher in the future than it is today. In other words, the average age of video game consumers should rise, even if penetration in younger cohorts is also increasing. We call this shift “riding the demographic curve”, and we illustrate what this might look like in Exhibit L. In our view, growth from an aging gamer population probably drives incremental user growth of ~100 bps/year for decades to come.

Lastly, for the first time ever, a generation of kids is being born to a generation of parents that grew up with console gaming. In our view, this probably translates to greater gamer penetration in young cohorts over the next decade. Not just that, we expect greater penetration of hardcore gamers on console and PC, which should have a positive impact on ARPU for the industry.

Tying It All Together: Industry Growth Outlook

There are basically 6 KPI’s that drive industry revenue: total gamers and ARPU for each of mobile, console, and PC. Where possible, we’ve reflected our expectations for each theme into one of these KPI’s.

On the gamer front, we expect growth to be driven by 1) generic population growth, 2) the aging gamer population from Theme 9, and 3) new gamers, driven by at least half of the themes discussed above. Exhibit M shows how we estimate each of these components have contributed to aggregate historical growth in global gamers, and what we expect in the future. Notably, we expect new user growth to slow down as mobile penetration plateaus, but for global gamer penetration to nonetheless rise steadily over the next decade.

More social gaming, eSports, streaming, and improving online multiplayer experiences all probably contribute to deeper and longer lasting engagement by users. In our view, this should translate into modest ARPU growth over time. Additionally, we expect more obvious near-term price inflation for console and PC games as the next generation of console is rolled out. On the flip side, mobile ARPU growth probably starts to slow as that market matures. Combined, we expect to see ARPU growth across platforms of 2.0-2.5% for the next decade, which is slightly higher than what we estimate historical ARPU growth to have been.

Exhibit N summarizes our base case industry growth expectations by platform, and breaks out contributions by both user and ARPU growth. In aggregate, we expect the industry to grow 6-7%/year in the base case. It’s worth mentioning that we do believe COVID-19 has been a tailwind for the video game space, but that some portion of the increase in engagement is probably transitory, which we try to reflect in this forecast. This industry growth forecast is a key driver behind the top-line estimates for each of the publishers we evaluate in the rest of this series.