We urge you to read Part 1 of the series if you’re unfamiliar with the video game space, particularly because many of the themes we discuss are both implicitly and explicitly reflected in our assessment of ATVI 0.00%↑.

Just like Jonah Hill went from a noob to an expert in 90 seconds (link), we too have ventured to go from noob to expert on ATVI very quickly. As such, we’re bound to have missed something, and therefore encourage you to reach out with criticisms, additions, or questions at the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

Investment Thesis

Activision Blizzard (ATVI) has some of the best video game franchises in the business, and combined with multiple industry tailwinds, we expect that the company should deliver mid-single-digit organic revenue growth over the next decade. For a variety of reasons, we expect that revenue growth will also be coupled with significant operating margin expansion, resulting in net income growth of nearly 10%/year. This business is relatively “capital light” in the traditional sense, with most growth capital being expensed. As a result, ATVI should accrue significant cash balances as net income grows. With net cash already at record levels, this should put ATVI in a great position to return cash to shareholders and/or pursue M&A. We also hold management in high regard, and trust that they will be effective stewards of this capital. Unfortunately, our analysis suggests that the market understands most of these positive themes and attributes, and it’s hard to argue that we have a meaningfully differentiated view from what the current share price implies (our base case is $90/share and the current price is $86/share). As such, ATVI is a great candidate for addition to our watchlist, but certainly not a pound-the-table idea today. That being said, we view this as a very high quality business, and in the absence of other ideas, it’s a great way to keep the ball in play.

Content

ATVI has three reporting divisions: Activision Publishing, which produces Call of Duty (CoD); Blizzard, which produces World of Warcraft (WoW), Diablo, StarCraft, and Overwatch; and King, which is a mobile-specific publishing team that ATVI purchased in 2016 and produces Candy Crush.

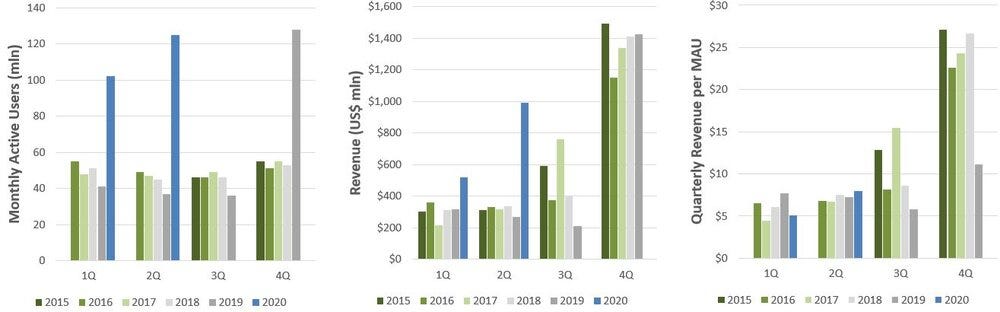

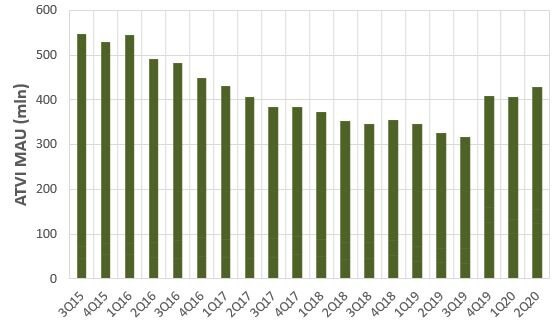

Activision Publishing releases annual CoD titles on PlayStation, Xbox, and PC. They sell roughly 25 million units per year on average, making it one of the best-selling titles in the world over the last decade. In our view, this is ATVI’s most valuable IP, and given the loyal fan base, we think it can be viewed as largely recurring revenue. In 4Q19, the company released Call of Duty Mobile in partnership with Tencent, and MAU increased by nearly 100 million. When the company released the F2P battle royale mode to the core CoD game, called Warzone, hours played on CoD increased by eightfold. Exhibit A shows how MAU and revenue changed with these two initiatives, and is a great example of how existing IP can be rolled out in new ways to drive revenue growth. It also shows that even though F2P ARPU is lower than that for full-game sales, the drastic step-change in players can make them equally, if not more profitable than the traditional paid game model. ATVI also just launched the Call of Duty League, which isn’t a major contributor to the bottom line today, but is another example of how good IP can be leveraged in new ways. Lastly, it’s worth nothing that Bungie had partnered with ATVI to publish Destiny, but ended the eight-year partnership (supposedly amicably) in 2019. This explains part of the drop in 2019 MAU/revenue for Activision Publishing, and highlights the risk of not owning your own IP.

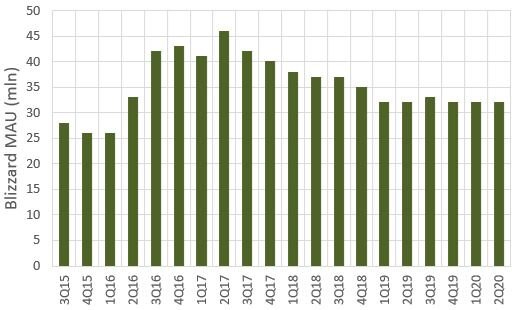

Blizzard has three core games that have been around for decades: Diablo was first released in 1996, StarCraft in 1998, and WoW in 2004. WoW is by far the most successful franchise (and probably the most successful PC franchise globally), with a significant portion of revenue coming from monthly or annual subscriptions. Blizzard releases new WoW content regularly, which keeps players engaged and willing to pay for subscriptions. ATVI tells us that subscription operating margins are much higher than the company average, making WoW one of their most profitable franchises. What’s unique about most of the Blizzard games, relative to Activision Publishing, is that the release cycle is really long. For example, the last StarCraft came out in 2010, and the latest Diablo was published in 2012, and revenue tends to be much higher in those release years. We expect StarCraft 3 and Diablo IV to be released in the next couple of years, and expect to see notable revenue growth as a result, particularly if Blizzard can monetize players with in-game content or subscriptions after the release. The Overwatch title was a recent addition and was first released in 2016. It was a huge success, accounting for more than 10% of ATVI’s revenue in fiscal 2016 and 2017, and trailing off thereafter. Exhibit B shows how the Overwatch launch impacted Blizzard’s MAU. Overwatch 2 is expected to be released in the next couple of years, and we expect it will be similarly successful. Blizzard also launched the Overwatch League, which has maintained relatively high viewership since launch.

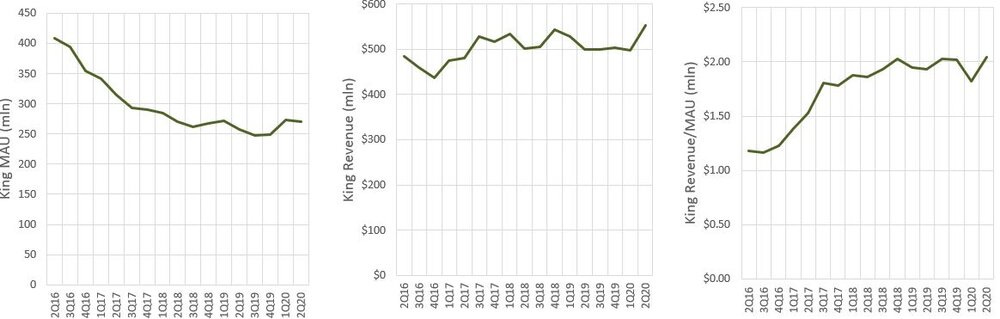

The final piece of the puzzle is King, which ATVI acquired in 2016. King owns Candy Crush, which is one of the most played mobile titles in the world, and contributes the vast majority of King’s revenue. Exhibit C shows that King’s MAU fell by 40% in the first three years following the acquisition, and yet revenue actually increased. ATVI says that Candy Crush has performed well through that period, so clearly what happened was that King stopped investing in poorly monetized games and focused more energy on games like Candy Crush (which has somewhere north of 100 mln MAU). We suspect that Candy Crush ARPU probably increased as well.

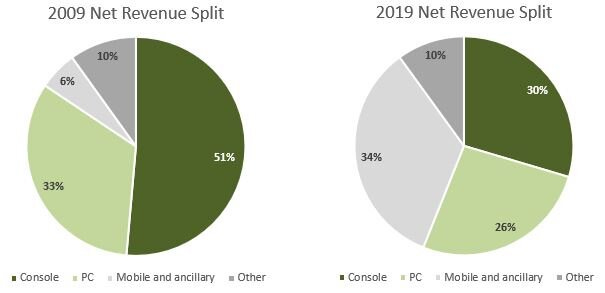

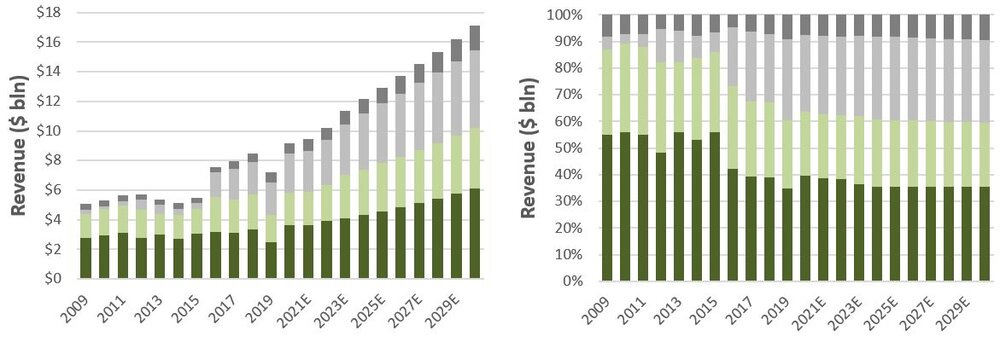

With growth in PC and mobile games, and lack of new content for console, the content mix by end market has shifted significantly over the last decade (Exhibit D). In 2009, mobile/ancillary was a miniscule portion of revenue, while console dominated the game slate. Today, ATVI has a fairly balanced split across the hardware spectrum.

Lastly, we note that a majority of ATVI’s revenue comes from just a handful of games: in 2010, CoD and WoW generated 73% of revenue; in 2015, CoD, WoW, Skylanders, and Destiny generated 71% of revenue; and, in 2019, CoD, WoW, and Candy Crush made up 67% of revenue. Additionally, ATVI tells us that these titles make up larger portion of operating profit than they do of revenue. This concentration poses a risk – if just one of those titles failed in the future, it could have a meaningful negative impact on profitability. We think this risk is low, but it’s still important to recognize.

Competitive Position

In our view, ATVI has a couple of competitive advantages today, mainly: fantastic brands, psychological switching costs for players, and scale. We’ll primarily use the Call of Duty franchise to illustrate these. The first CoD title was released in 2003 by a new development studio called Infinity Ward (purchased by ATVI). The first release had a Metacritic score of 91 for PC, making it one of the best rated games of all time (top 2.5%). Since then, a new CoD title has been released almost every year, and they consistently garner high Metacritic scores – the average score sits at the top 15% of all games in the Metacritic score distribution (Exhibit F).

There are plenty of criticisms levied at the usefulness of Metacritic scores, but an Eludamos research paper from 2013 shows that they do have some predictive value for unit sales (Exhibit G).

Great content is a competitive strength, but it’s not a durable competitive advantage by itself – after all, the CoD franchise has sold more than 300 million units to-date, making it one of the best-selling franchises ever, and yet 2,000+ games from the last two decades have received higher Metacritic scores without seeing anywhere near CoD’s success. One of the primary differentiating factors is brand value. Hamilton Helmer talks about brands in his book 7 Powers, and highlights that a brand only has value for either one or both of these reasons:

“Affective valence: The built-up associations with the brand elicit good feelings about the offering, distinct from the objective value of the good.”

“Uncertainty reduction: A customer attains ‘peace of mind’ knowing that the branded product will be just as expected.”

In the case of CoD, we suspect the primary brand value is in uncertainty reduction. Activision Publishing has consistently produced high-quality content with familiar gameplay for almost two decades. If a user has already played three successive iterations of CoD, they can trust that the next iteration will deliver a familiar experience, with little risk of disappointment. When making the choice between the next CoD game and an unknown, the safe bet is CoD, particularly considering how many highly marketed AAA games end up being a flop (like Titanfall 2 or Anthem). As Hamilton notes, a “strong brand can only be created over a lengthy period of reinforcing actions (hysteresis), which itself services as the key Barrier”, and CoD has nearly two decades of positively reinforcing experiences. Compare that to another first-person-shooter (FPS) game like Overwatch, which had a much higher Metacritic score when it was released than the same CoD title released that year, but a fraction of the unit sales and MAU. In addition, Overwatch 2 will probably be released 5 years after the first Overwatch, whereas CoD is launched annually – exacerbating the difference in cumulative unit sales per franchise. Lastly, CoD’s strong brand makes it easier for ATVI to increase pricing on the next generation of consoles versus a brand new title. In our view, brand value is greatest for CoD, but probably matters for WoW, Diablo, StarCraft, and Candy Crush as well. In time, it might also matter for Overwatch.

Increasingly, we believe CoD is also behaving like a mini social network. As such, ATVI benefits from many of the things we touched on in Theme 6, particularly increasing psychological switching costs. Once we learn how to play CoD, our friends all play CoD, and we’ve purchased items to customize our avatars, we’re much less likely to switch to another game. In addition, affective valence grows as we create “identities” by purchasing unique avatars, guns, vehicles, etc.: we build up positive associations with the CoD brand through our unique digital identities and social interactions. Even if the gameplay of another title was equally as good, the identity tied to the CoD brand likely prevents some users from leaving the game. This is a really difficult feeling to create from scratch, and we suspect that this social element to gaming is still in the early innings.

Most large gaming franchises like CoD also receive some scale benefits. For example, Activision Publishing likely spends upwards of $200 mln on development and marketing for a single CoD title, while other FPS games like Titanfall 2 can barely generate that much in revenue. Activision has made some hilarious live action trailers with guys like Jonah Hill and Sam Worthington (link) or Michael Phelps and Danny McBride (link), and obviously most games can’t afford to include stuff like this in their marketing campaigns. More recently, streaming services like Twitch host streamers like NICKMERCS that almost exclusively play CoD, and who routinely have 50k+ viewers tuning in. These streamers promote new releases on their streams, and can reach massive audiences of very engaged consumers. We suspect that the unit cost of marketing through these channels is much cheaper than some of the more traditional ad mediums. Lastly, Activision promotes new titles with in-game releases. For example, the F2P Warzone mode held a special in-game event to release a trailer for the new 2020 Cold War game expected later this year. During the event, nearly one million people tuned into Twitch to watch the reveal in real time, on top of all the people playing the game during the event. That’s an insane audience, and once again, the per unit marketing cost has to be a miniscule fraction of traditional mediums (it’s basically just lines of code). Brand new games obviously don’t have that benefit, and smaller games can’t reach the same audience through in-game events or streaming services.

Scale also matters for game development. When developers release a brand-new AAA game and don’t rely on third-party engines, they typically have to create all the software from scratch. Large enduring franchises can utilize the game engine from the previous release and don’t need to rethink core game mechanics in the same depth. In addition, games with lots of MAU can be monetized with in-game transactions, and will therefore have the financial capacity to continually release new content. The CoD Warzone mode has tens of millions of MAU that support new content through in-game purchases. To state the obvious, if a game has only 1 mln MAU vs. a game with 60 mln MAU (monetized at similar rates), the new content for the small game is going to be nil or sparse in comparison – and, new content keeps MAU high, which helps drive more monetization, which helps drive new content, and repeat. These scale benefits matter a lot because of the increasing development costs we discussed in Theme 7, specifically for console and PC.

Lastly, scale matters at the company level for three additional reasons: first, ATVI has great data and insights from other games that they can use to understand what works and what doesn’t work when developing and marketing a new game; second, because of their size, ATVI likely pays a lower take-rate on digital platform sales than independent or smaller publishers; and third, some shared S&M and G&A reduces the unit cost of those expenses per game.

Notably, most of these competitive advantages should lead to excess returns from the suite of large established franchises that ATVI has today. What they don’t help with in a meaningful way is direct competition with other major publishers – for example, ATVI has no edge over EA in most sport categories.

Strategy

For many years, ATVI’s strategy has been to increase reach (more players and viewers), engagement (more time per player/viewer), and player investment, by reinvesting in proven existing franchises and adding new franchises. A number of metrics indicate that they’ve done a poor job achieving some of these goals: PC and console MAU have hardly changed, ARPU has remained effectively flat in both categories, and global PC and console market share was therefore lower in calendar 2019 than any other point in the last 8 years. What’s really interesting is that management seems well aware of this, and has been for a while:

2014 Annual Report: “While our incredibly talented team delivered another record year of earnings per share in 2014, these figures don’t provide a perfect picture of our performance, as they don’t emphasize what we could have done better, which is a lot”

2015 Annual Report: “We continue to improve our allocation of capital. While our employees have much to be proud of, we haven’t grown operating profits the last few years at a rate that we believe represents the opportunities we have from the growth in the overall market. The overall market for interactive entertainment is growing at 13%. We have grown earnings per share over the last few years, but this has largely come from non-operational activities, and we intend to return good growth to our operating businesses over the next few years”

2016 Annual Report: no overarching quote, but they indicate that Activision and King underperformed expectations, specifically Activision: “We assure you that lots of effort is being expended to correct the mistakes we made (there were quite a few) and we are confident we will get back on track for growth in future years”

2017 Annual Report: “The markets we serve grew faster than we did last year, but we are determined to change that over the next few years”

2018 Annual Report: “Some of the important metrics by which we measure our success are reach, engagement and player investment, and while we did have record financial results in 2018, we didn’t achieve the reach, engagement and player investment goals we set for ourselves. In an industry with great growth prospects, our organic growth over the last few years has not been satisfactory to us”

2019 Annual Report: “Our top and bottom-line results were down significantly from our prior year performance, even though our industry grew during the same period. This isn’t the level of excellence we have maintained for most of the last 30 years we have managed the company. It is said, “Vision without execution is hallucination”, and our 2019 results were impacted by poor execution managing our content pipeline and not moving quickly in the management of our costs”

The good news is that this self-described operational underperformance seems to be changing.

The 2014-2018 annual reports highlight that ATVI was pursuing three new initiatives: consumer products, television and film, and eSports. Clearly consumer products and television/film have been flops, and ATVI has de-emphasized those initiatives over the last year while ramping up what’s working: eSports. Over the same period, we also get the impression that ATVI was underinvesting and stretching development resources across too many initiatives, which culminated in “fewer big franchise launches in 2019 than in past years”. In 2018, ATVI seems to have realized that this was a problem and went on to A) increase developer headcount by 20% at their best existing franchises, B) incubate a narrower range of high-potential new franchises, C) eliminate investments in periphery games/initiatives, and D) consolidated a number of back-office, commercial, and marketing functions to better serve the highest potential content teams.

All of these changes are clearly translating into improved operating performance, with MAU in 2Q20 up 30% y/y (Exhibit H), and organic 2020 revenue growth expected to be higher than any point in the last decade. Part of this growth is COVID-related, but a substantial portion is clearly because of new content releases like Call of Duty: Warzone and Call of Duty Mobile, growth in eSports, and strong momentum from existing games like Overwatch, WoW, and Candy Crush. What we find most encouraging is that increased investment in the “best existing franchises” like Call of Duty is clearing paying off, and management seems keen to follow the Call of Duty roadmap for other franchises in its library (paid game, F2P, mobile, etc). As they focus on leveraging existing IP and very selective new IP, we expect to see reach, engagement, and player investment all increase.

If we ignore some of the operational/content missteps, the broader capital allocation record is fantastic. ATVI clearly rank-orders investment opportunities based on incremental ROE, and has a track record of decision making that has created tremendous value for shareholders, including very opportunistic share buybacks and strategic M&A (we’ll expand under Performance). They also pay a modest dividend, but generally accrue more cash than they pay out, which leads to fairly large and growing cash balances. The management team has obviously preferred to maintain extreme financial flexibility, which explains why the large cash balances accrue. That being said, we’d expect that they continue to pursue buybacks and M&A over time. To better illustrate how they think about capital allocation, we’ve included this snippet from their 2015 annual report about the King acquisition (emphasis our own):

“The type of games that are successful on mobile phones, and the way you make and market these games, is different from games on PCs and consoles. We didn’t really know how to do this well. To take advantage of this opportunity, we decided to acquire a company with the skills and capabilities to make mobile games. We needed to find one that met our stringent criteria for how we allocate capital through an acquisition. As we have outlined many times before in these annual reports, we employ five principles to evaluate an acquisition or an investment. They are:

Great management with a long-term orientation

A proven history of profitable operations

Proven franchises or a proprietary technology (preferably both)

Accretive to our operating model

Non-dilutive (preferably accretive) for our shareholders

We wanted a company as committed to product excellence as we are. We wanted a great management team that has the right balance of creativity and commercial sensibility and operates with the same integrity that is the hallmark of our culture. We waited for the “fat pitch,” as Warren Buffett likes to refer to investment opportunities that only come with patience. With King we hit the ball out of the park. When we first met the management team of King a few years ago, we were impressed. We watched as they operated their business since that first meeting, and we were even more impressed. It was hard not to be. Like Activision and Blizzard, King has an established portfolio of beloved franchises—Candy Crush, Farm Heroes, Pet Rescue and Bubble Witch—and they have new potential franchises in development. They have diverse audiences in 196 countries, and their games are played 1.4 billion times a day. King management is philosophically aligned with our strategic goals of building enduring franchises. Like Activision and Blizzard franchises, King games can be expanded and nurtured year-round. King also has incredible potential upside from the careful integration of advertising into their games. Their network is bigger than Twitter or Snapchat, and they have well over 20 billion hours of game time to monetize. They also have exciting new content and services planned to further enhance the player experience. We paid a very reasonable price for King at six times their 2015 adjusted EBITDA, and as a result, with over 500 million users each month, we are now the world’s largest gaming network. To understand the scale of this network, on a global basis only Facebook, YouTube and WeChat have bigger audiences.”

To summarize, we think ATVI is on the right track to execute on their strategy of growing reach, engagement, and player investment, despite a few missteps along the way. At the same time, the capital allocation decision-making process has been consistent and value additive, and we see no reason for that to change under this management team.

Performance

ATVI’s financial performance has been impressive, with EPS growth exceeding 20%/year over the last decade, despite revenue growth of just 4%/year (slightly below industry growth). A good deal of this success is driven by increasing gross margins that would have benefited all the publishers (particularly because of the shift from physical to digital), but two capital allocation decisions specific to ATVI also deserve some mention. First, in 2013, ATVI repurchased a third of their outstanding shares from Vivendi at $13.60/share – that investment has “returned” 28%/year versus the cost of debt they used to fund the purchase at ~5%. In hindsight, this created tremendous value for remaining shareholders, and explains effectively all of the difference between EPS and net income growth over the last decade. The second great decision was the purchase of King in 2016 for ~5-6x EBITDA, which increased total company ROE by 3-4% (ignoring the unrelated one-time tax charge in 2017).

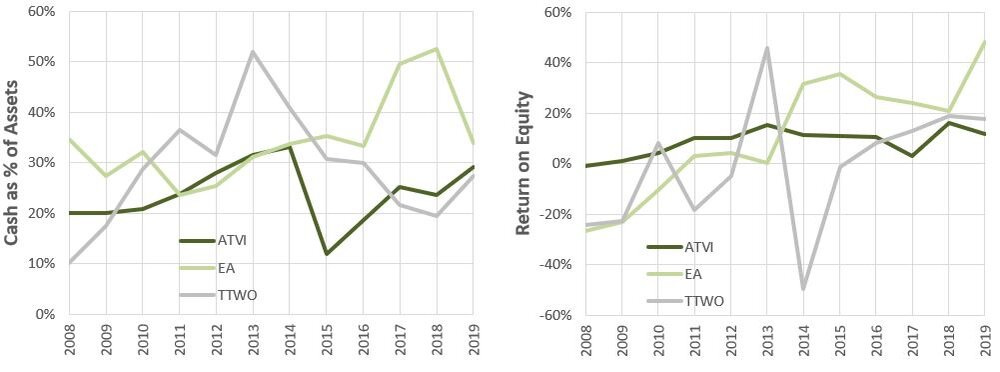

We note that ATVI’s ROE increased to ~10% in 2010 and was relatively flat until the King acquisition in 2016, and now sits in the mid-teens range, which is good (consistently exceeds cost of equity) but not exceptional. However, if we adjust for the large cash balance, ATVI’s ROE has generally been greater than 20% for a decade. Through one lens, the cash balance could be viewed as a drag on total returns, but through another, it’s enabled ATVI to opportunistically pursue very accretive buybacks and M&A, which seems to be increasing unadjusted ROE over time. Nevertheless, when we compare ATVI’s cash balance and ROE vs. EA and TTWO, we see that the other publishers carry similar levels of cash, but have been generating higher ROE’s than ATVI for a number of years now (Exhibit J).

We suspect that ATVI’s lower ROE is purely a top-line issue, which we highlighted in the strategy section above. The good news is that we think ATVI has addressed some of their content shortcomings, and we expect to see top-line growth rebound in the next 1-3 years, which should lead to improving ROE.

Financial Position

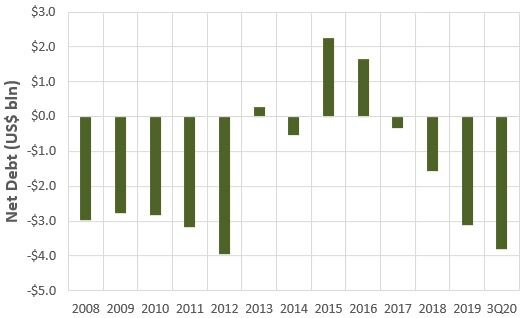

In 2013, in connection with the Vivendi share repurchase, ATVI borrowed $4.7 bln under a term loan and series of notes. In 2018 they repaid the term loan and redeemed some of their outstanding notes, which took the remaining debt balance down to $2.7 bln, where it remained until very recently (currently $3.6 bln). They utilized some cash in 2016 to purchase King, but generally their cash balance has increased over time, and even though some of the cash balance is likely ear-marked for debt repayment (maturities in 2021/2022), the company’s net cash position is close to record highs as of 3Q20 (Exhibit K).

All the publishers expense their biggest “growth spending” items, which include software development costs and S&M, so free cash flow conversion is typically >=100%. As a result, cash accumulates fairly rapidly in the absence of M&A or distributions to shareholders. Even though ATVI’s net cash position is getting quite large, we suspect that it might continue to grow for a couple years. Management has a track record of waiting for the “fat pitch”, so barring an attractive opportunity to repurchase shares (we don’t think that exists today), or a compelling M&A target (we haven’t been able to identify a target or need), we believe that their preference is clearly to wait-and-see over distributing to shareholders through something like a special dividend in the near term. That said, the company does pay a very modest dividend (~20% payout ratio), which more-or-less grows in-line with EPS – we expect that payout to rise modestly over time, particularly in the absence of M&A.

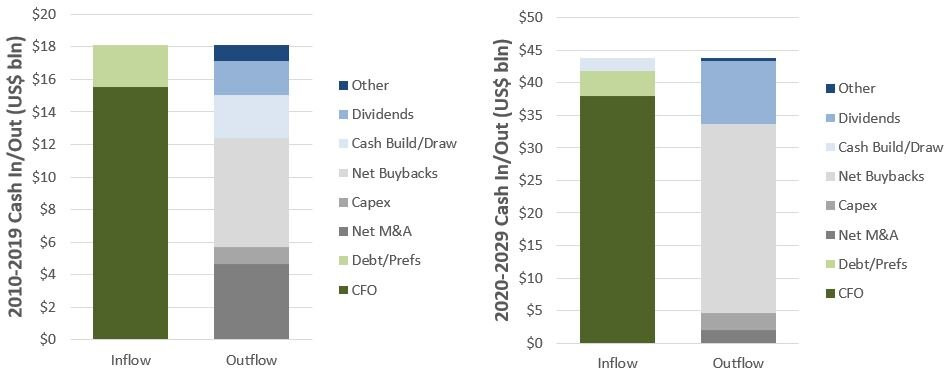

Exhibit L shows historical sources/uses of cash, and it’s remarkable that CFO has funded basically all of ATIV’s M&A, buybacks, and dividends. Our 2020-2029 assumptions show that barring some very large M&A, ATVI is in a position to meaningful increase distributions to shareholders relative to the last decade.

Management & Governance

The ownership and management history of ATVI is an interesting one (we wish someone would write a book about this already). Robert (Bobby) Kotick has been the CEO for 30 years, and this NYT article from 2012 is a fantastic background on Bobby and the rise of ATVI (link), but the gist of it is this: Bobby and a group of investors bought a floundering Activision (then Mediagenic) for a measly $500k in 1990, and went on an M&A bender for thirty years to build the biggest independent video game publisher in the world. It’s hard to really know if this success is luck or skill, but many of their acquisitions have been shockingly successful:

Purchased Infinity Ward, the creator of Call of Duty, in 2003 for $5 mln. The franchise now generates +$1,000 bln of revenue every year.

Merged with Blizzard in 2008, the gaming division of Vivendi, and then bought out Vivendi in 2013 for what turned out to be literally pennies on the dollar. The Blizzard PC IP is some of the best on the planet.

Purchased King in 2016 for a measly 5-6x EBITDA, and now own one of the most popular mobile games in the world, and have an internal developer team to help roll out new mobile games with their existing IP.

Bobby routinely pays homage to The Oracle of Omaha in ATVI’s annual letters, and overtly obsesses over optimizing capital allocation decisions more than most other CEOs we’ve come across (clearly taking inspiration from Warren). In fact, he has indicated that Warren is one of his most important mentors. At 57 years old, he’s young by the CEO standard, and yet has 30+ years under his belt of successfully growing and operating the same interactive entertainment business. During that time, he’s made his fair share of mistakes, which he seems to admit openly; but, in our opinion, that feedback loop has created a more astute manager and capital allocator, and has therefore been a good thing. Lastly, his role as CEO isn’t just a job, it’s a passion, and ATVI is his baby (Bobby also owns 2.5 mln shares valued at ~$190 mln). As potential ATVI investors, we love that Bobby is at the helm. In an interview earlier this year, he was asked if he’d like to keep running ATVI or explore something new like running for public office, and he said: “I couldn’t imagine doing anything different… for the next 30 years, if I had the opportunity to keep doing what I’m doing, I would love doing that”.

Other ATVI executives, like CFO Dennis Durkin, bring their own set of unique experiences. Dennis worked at Microsoft for 12 years in the corporate development group and as the CFO/COO of Xbox, before joining ATVI in 2012 as the CFO with an increasing breadth of responsibilities. Microsoft is simultaneously a competitor and a partner in the gaming ecosystem, and the perspective that Dennis brings is undoubtedly valuable.

Just like Bobby, Brian Kelly is another ATVI staple, who joined the company with Bobby in 1990 (when they were both in their mid-20’s), joined the board in 1995, and has been the Chairman since 2013. It’s a little disappointing that we haven’t been able to find any interviews or color on Brian, and therefore haven’t been able to develop a view on his value to the organization. What we do know, is that Brian is the single largest insider owner of ATVI stock, with nearly 5.0 mln shares valued at ~$380 mln. As Chairman of the board, with no other public board seats, such significant equity interest, and long tenure, he’s clearly aligned with ATVI shareholders. When we evaluate the incentives/competencies of the board as a whole, we don’t come across any brown M&Ms.

Despite our generally positive view of the management team and board, there are a couple culture/governance concerns we need to think about. First, despite the generally positive view of Bobby in the investment community, he’s often villainized by people in the gaming community. For example, Tim Schafer, a game designer and CEO of Double Fine Productions, was once asked for his thoughts on Bobby Kotick – his response:

“His obligation is to his shareholders. Well, he doesn't have to be as much of a dick about it, does he? I think there is a way he can do it without being a total prick”

This type of criticism is common, and seems to be rooted in the fact that the archetypal game designer and Bobby have very little in common. Game designers spend years dedicated to a single title, and that title becomes a work of passion. If someone, like Bobby, decides that your work of passion doesn’t pass muster (probably because of financial expectations) and cancels the project, feelings are going to be hurt. Similarly, the gaming community was furious when ATVI cut 800 staff in early-2019 despite record EPS in 2018, and excellent pay packages for executives. Glassdoor reviews for ATVI overall, and of the CEO, have subsequently declined significantly as a result (Exhibit M). These reviews are substantially worse than the other publishers. We suspect that corporate culture is significantly more important to business success for creative enterprises, so this deterioration worries us a little. On the flip side, 800 people were laid off and there are only 193 reviews, so if even 5-10% of laid off employees left a bad review it would massively skew the data, and might not be representative of current culture/opinions. Also, in fairness, 2019 proved to be a much worse year than 2018 because of the small release pipeline, so the move to refocus on the most promising initiatives was probably a smart one for the organization. Nevertheless, this culture uncertainty adds an element of risk to our forecasts that is reflected in our bear case through market share loss.

The second cause for concern is what some shareholders are calling “excessive executive compensation”, which could indicate poor governance. CtW Investment Group represents union-sponsored pension funds, and was the most vocal against the say-on-pay vote in 2019 and 2020, likely because of the layoffs ATVI undertook in 2019 in conjunction with a huge pay package for Bobby. CtW largely leans on arguments made by ISS, who recommended that shareholders vote against the say-on-pay proposal. In response to ISS’ recommendation, ATVI provided what we think is a strong rebuttal (here). Nonetheless, 2020 say-on-pay support was notably worse than years prior. Despite the outcome of the vote, we don’t actually think ATVI’s executive compensation practices are unreasonable or indicative of bad governance, even if it might have been a little tasteless to simultaneously pay the chief executive $30 mln while laying off 800 employees.

Valuation & Scenarios

Revenue

We spent a lot of time trying to create a bottom-up revenue forecast using estimates for game releases, unit sales, unit prices, and MTX per user. What we found is that this was a costly and ultimately low-value exercise, particularly over a long time horizon. Instead, we take a two-stage approach to forecasting, where the first stage leans on a combination of intuition and wisdom of crowds (consensus), and the second stage leans on market share estimates and our long-term industry growth forecast from Part 1 of the series.

For fiscal years 2020-2022, we use a revenue forecast that’s more-or-less in line with consensus, and the reason is simple: we see no compelling reason why we’d have differentiated expectations on near-term estimates from the dozens of analysts and associates that regularly talk to the company about the game slate and tackle short-term revenue forecasts from a bottom-up perspective.

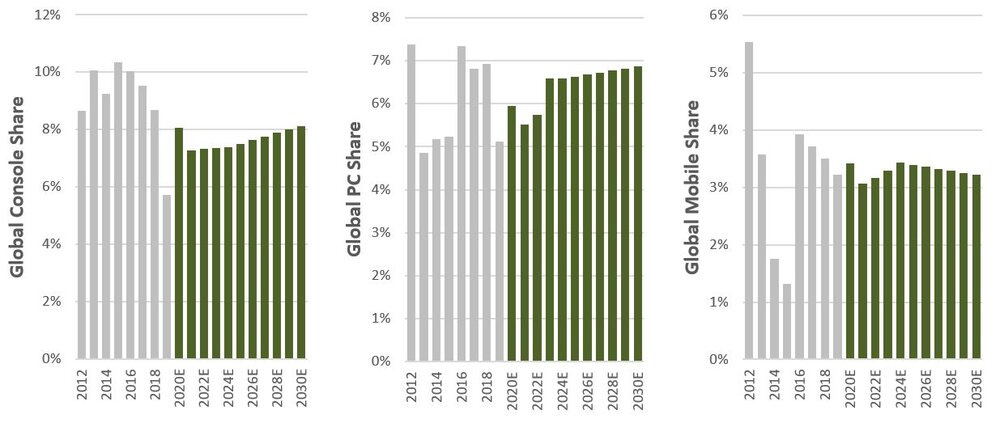

Beyond fiscal 2022, we make assumptions about ATVI’s long-term market share for each of console, PC, and mobile (Exhibit N), and apply those estimates to our segment industry forecasts.

For console, we expect market share to be lower than it was pre-2019, largely because ATVI lost the Destiny franchise last year and we don’t expect them to organically replace it (proportionally) with an equally successful title in the base case. That said, Call of Duty is an exceptional franchise that we think will grow in value over time, particularly as streaming viewership and eSport popularity picks up. Overwatch is also in it’s relative infancy, and could become a much bigger contributor to console revenue in the future. As such, we model modest share gains from 2022 onward.

For PC, we note that Blizzard hasn’t refreshed some titles like StarCraft and Diablo in a long time, which could take share if follow-up titles were released. We also see Call of Duty and Overwatch as being meaningful future contributors to PC revenue. We’re guessing that there are more Overwatch players on PC than console, so that probably has a disproportionately positive impact to PC revenue when subsequent titles are released. As such, we assume slightly higher long-term market share than the 2012-2019 average.

As we touched on in Part 1, ATVI has lots of IP that’s historically geared toward console and PC which they could roll out to mobile. Call of Duty Mobile was a great example of this, and explains the modest increase in market share in 2020, but there is lots of additional potential which could drive meaningful mobile growth like the yet-to-be-released Diablo Immortal, or a totally speculative StarCraft mobile. On the flipside, mobile is a very competitive space where puzzle games seem to dominate, and publishers need to run very fast just to stand still (keep market share flat). Outside of the King acquisition, ATVI has effectively lost share in mobile in every year except 2020. As a result, even though we think ATVI will do a better job at capturing the mobile opportunity in the future, we suspect new content will largely help to keep market share flat.

Lastly, we capture the value of eSports in a separate line item: Other, which historically represented revenue from ATVI’s distribution business, but is increasingly reflecting contributions from the Overwatch and Call of Duty leagues. We assume that the distribution business largely winds down as physically purchased games lose share, but that eSports grows exponentially. The 2030 revenue forecast of $1.5 bln basically assume that three leagues each earn $500 mln/year from a combination of sponsorships, broadcasting rights, and merchandise.

All of these assumptions translate into a revenue growth CAGR (from fiscal 2020 to 2030) of 6.5%/year, versus growth over the last decade (2010-2020) of 6.0-6.5%. We note that historical growth was probably 65/35 organic and inorganic respectively, and that our forecast in the base case is predominately organic growth. The implication is that we expect much better organic top-line growth from ATVI in the future than they’ve achieved in the past.

As a final note on our revenue forecast, we want to highlight how difficult it is to forecast market share relative to some other drivers, and emphasize the importance of scenario analysis to really understand the range of outcomes for valuation.

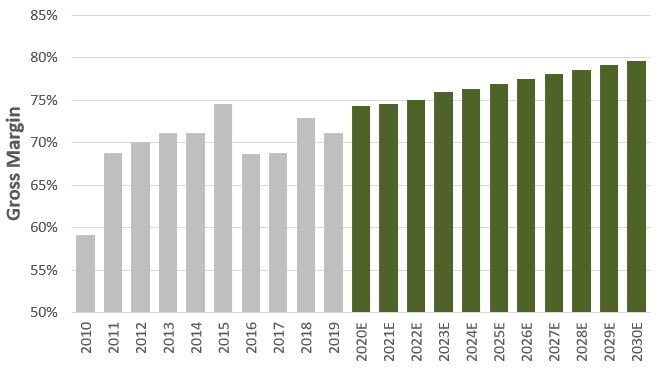

Gross Margins

We expect that gross margins for ATVI will rise over the next decade, and there are two primary drivers behind this assumption. First, even though physical sales represent a minority of total revenue today, we expect that physical will continue to lose share. Our base case takes physical revenue, as a proportion of the total, down from 14% in 2019 to 4% in 2030. Part of this is proportionally faster growth in mobile and in-game sales, and part is lost physical share in console and PC. As we explain in Part 1, digital revenue has higher gross margins than physical, and this continued shift explains about half of our margin expansion.

The other half of gross margin improvement is rooted in our view that digital platform fees for PC and mobile will fall. For PC, we assume that the realized digital platform fee falls from an estimated 23% in 2019 to 15% in 2030. For mobile, we assume fees fall from 30% to 23%. We expect some pushback on our mobile assumption, so for those that are skeptical, the decrease in mobile platform fees adds ~$4/share to our estimate of fair value - notable, but not a thesis-changer.

Combined, Exhibit Q shows that these changes should result in gross margin expansion from 74% in 2020 to 79% in 2030.

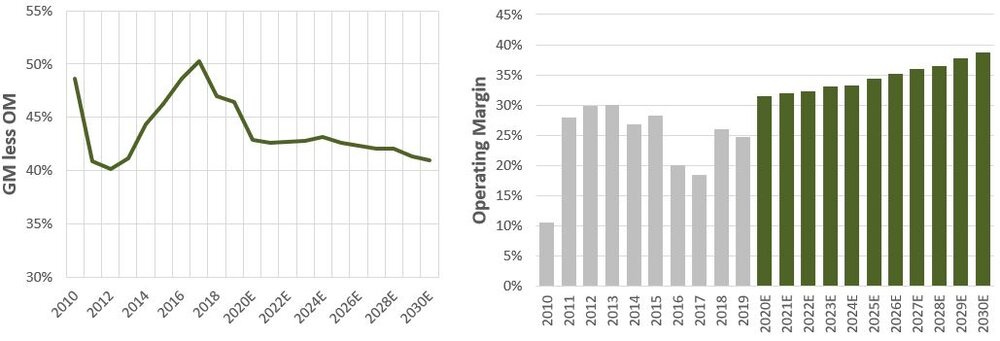

Operating Margins

There is some historical data to support the notion that publishers benefit from economies of scale on S&M and G&A, although the specific historical data for ATVI is messy and complicated by acquisitions. Nevertheless, we do expect modest leverage on S&M and G&A as ATVI grows. We also expect a modest reduction in R&D as a percentage of sales as ATVI focuses on their most important franchises. As we also highlighted in the Strategy section, ATVI just “consolidated a number of back-office, commercial, and marketing functions to better serve the highest potential content teams”. That change should translate to proportionally lower costs in all of these categories. Margins should also expand on eSports revenue as that business scales. Lastly, we expect in-game revenue will grow proportionally faster than full-game sales, which comes with proportionally lower expenses. Exhibit R reflects all of these assumptions in our operating margin forecast. The graph on the left shows the difference between gross margins and operating margins, which isolates for the benefits of proportionally lower S&M, SG&A, and R&D. The graph on the right shows that we take operating margins up from an expected 31% in 2020 to 38% in 2030 (7% expansion vs. gross margin expansion of just 5%).

Underutilized Balance Sheet

The last thing we grapple with in valuation is how to think about the $7+ bln (and growing) cash balance. On the one hand, Bobby has a track record of opportunistically putting that cash to use in very accretive ways, where ROE exceeds their cost of equity. On the other hand, ATVI has always carried a high cash balance (despite Bobby’s best efforts), and typically has negative net debt, in which case cash is a perpetual drag on returns. In the worst case scenario, ATVI probably sits on a cash balance proportionally higher than historical levels, returns some excess cash via systematic buybacks or dividends, and doesn’t pursue any needle moving M&A. In the best case, ATVI structurally reduces cash such that net debt is modestly positive, and they do so through some combination of opportunistic buybacks and accretive M&A. In our base case, we basically assume something in the middle: ATVI takes ND/EBITDA to 1.0x long-term, and systematically returns excess cash to shareholders (ROE = cost of equity), or pursues M&A where ROE is more-or-less in line with our cost of equity.

The Outputs

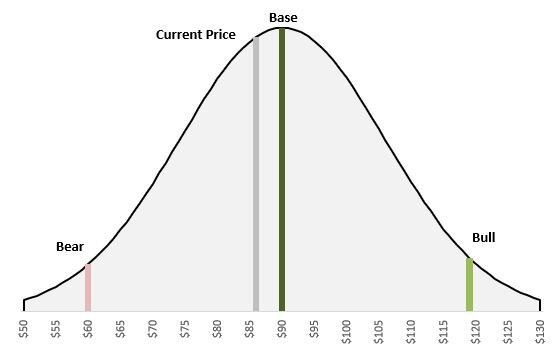

In the base case, EPS growth is 11-12%/year from 2020 to 2030, while ROIC ex-cash goes from 26% in 2020 to 51% in 2030. Our base case estimate of fair value works out to $90/share. Exhibit S shows a summary of the assumptions behind our DCF, and our model can also be found at the top of this post.

We ran two additional scenarios, meant to represent the 10% and 90% outcomes in a probability distribution (the bear and the bull). Exhibit T shows how we arrive at each scenario, using the base case as a starting point.

If we pretend that the range of future outcomes follows a perfectly normal distribution, we can plot our bear, base, and bull scenarios versus the current share price, as we’ve done in Exhibit U. This helps us visualize how the current price compares to the range of future outcomes we’ve constructed, and in this particular instance, it’s hard to argue that we have significantly differentiated expectations from the market. Gun to our head, we’d take the over on current price ($83/share), but our conclusion is that the market has priced in many of the positive secular themes driving ATVI’s distributable cash flow growth. Said differently, just a few small changes to our top line growth or operating margin estimates would take our fair value estimate down to the current price. Incremental investors should earn close to the cost of equity we use of 8%. For now, we’ll add ATVI to our watchlist and wait for a clearer signal that market expectations are materially different from our own.

What would the 10th Man say?

There are a couple things we have not yet explored in this series, like VR/AR and the metaverse. There are good reasons we haven’t bothered going down those roads, but we suspect a 10th (Wo)Man would point there and say we’re ascribing no value to some big potential real options, and if we did, it would show that the market is significantly mispricing this business. For example, an AR/VR version of Call of Duty is probably going to fetch an ARPU orders of magnitude higher than current ARPU. Even if margins ended up being unchanged, revenue growth could end up being much higher. Our rebuttal would be that the install base of AR/VR hardware is close to nil, will take a long time to roll out, and other developers might dominate in that space. Even so, we do use a 3% terminal growth rate (instead of 2%) to reflect some of these positives.