Berry Global (BERY)

The largest plastic packaging business in the world

Disclaimer: I’m currently a BERY shareholder

As always, if you have any pushback, comments, or questions I encourage you to reach out. You can comment below, find me on Twitter, or reach me at the10thmanbb@gmail.com. You can also find my DCF model below.

Intro to Berry

Berry Global (BERY 0.00%↑) is often described as one of the largest plastic packaging manufacturers in the world. They make stuff like yogurt containers, water bottles, drink cups, fresh meat packaging, barrier films for cereal and cracker boxes, aerosol caps, pharmaceutical containers, shampoo bottles, and pales. But technically they make more than just packaging products. For example, Berry also makes diapers, adhesives, pipeline corrosion products, surgical gowns/masks, disinfecting wipes, table clothes, filters, and a dizzying array of other plastic-based products. Whether it’s packaging or some other plastic-based product, I’ve seen references that indicate Berry produces >100,000 SKUs. Odds are, there are dozens of products in your house right now that Berry – or a company like Berry – had a hand in manufacturing. Hell, I think it’s likely that you’ve picked up, touched, or somehow interacted with a specific Berry product at least once today. Plastic gets a bad rap (which I’ll touch on later), but it’s hard to overstate how integral these products are to everyday life around the world.

Today, Berry owns or leases a little more than 250 manufacturing facilities globally and serves more than 10,000 customers. Some of their largest customers include General Mills, Kraft, McDonalds, Walmart, Coca-Cola, Pepsico, Bayer, Sherwin-Williams, Johnson & Johnson, CVS, L’Oreal, Avon, Proctor & Gamble, Home Depot, Costco, Kimberly-Clark, Dannon, and Unilever. It sounds silly to say, but in most cases I think Berry is selling mission-critical products to these accounts. Coca-Cola can’t sell cola without a bottle and tethered lid. Dannon can’t sell yogurt without the cup. General Mills can’t sell cereal without the barrier film. Proctor & Gamble can’t sell shampoo without the bottle. Kimberly-Clark can’t sell Huggies without non-woven fabrics. Despite these big names, no single customer accounts for more than 5% of revenue, and the top 10 customers represent just ~15% of revenue.

This is obviously a very diverse business, but another thing I found particularly impressive was a note from Berry’s S-1 (from 2012) where they indicated that:

“76% of net sales during the 12 months ended June 30, 2012 were in markets in which management estimates we held the #1 or #2 market position”.

As I understand it, “markets” are defined narrowly (for example, adult incontinence products in Brazil). Even still, holding the #1 or #2 position in most of their markets is impressive, and I suspect that continues to be the case today given that the business is ~3x larger than when they IPO’d.

Berry splits up the business into four segments:

Consumer Packaging International (CPI; 30% of 2022 sales)

Consumer Packaging North America (CPNA; 24% of 2022 sales)

Engineered Materials (24% of 2022 sales)

Health, Hygiene, and Specialties (HHS; 22% of 2022 sales)

The CPI and CPNA segments consist of all the rigid consumer plastic products that would typically come to mind when you think of packaging – many of which I touched on above. Where CPI and CPNA largely produce rigid plastics (something solid like a yogurt cup), the Engineered Materials segment focuses on flexible products/films like garbage bags, PVC films for fresh meat, electrical tape, heat-shrinkable coatings, and stretch films for storage/shipping. Finally, HHS covers a very wide range of products including feminine care, diapers, deodorant sticks, disinfecting wipes, drug delivery products (like inhalers), disposable gloves, acoustic material, billboard films, and solar films. Exhibit A shows historical revenue contribution by segment, alongside the revenue split by geography and end market.

In Exhibit B I also break out historical EBIT by segment alongside total adjusted EBITDA and adjusted EBITDA margins. Note that EBIT includes restructuring costs and amortization of acquired intangibles, which explains why it’s more volatile than adjusted EBITDA. Regardless of how I slice it, Berry has grown very rapidly over the last fifteen years for an old-school industrial business. Adjusted EBITDA grew at a CAGR of 15%, 11% and 14% over the last 5, 10, and 15 years respectively, and revenue grew at 11%, 12%, and 17% over the same periods.

It's important to note that most of Berry’s historical top-line and bottom-line growth was a function of M&A. This was a roll-up story, through and through. It all started in Evansville, Indiana when Robert Morris bought a single injection molding machine to make plastic aerosol caps in 1967. That business was initially called Imperial Plastics. In the early-80’s, Jack Berry Sr. acquired Imperial Plastics and renamed it Berry Plastics Corporation. Jack subsequently opened a new plant in Nevada and acquired another business called Gilbert Plastics. He then sold this larger entity to a private equity firm called First Atlantic Capital in 1990. Under private equity ownership, Berry Plastics Corporation started consolidating other plastic manufacturers across the United States and completed 15 acquisitions before Goldman’s private equity group acquired the business in 2002. Goldman continued the private equity hot potato game and sold Berry in 2006 to yet another group of private equity buyers led by Apollo. Under both Goldman and Apollo ownership, Berry continued to roll up plastic manufacturers across the United States, and by the time Apollo took Berry public in 2012 they had completed more than 30 acquisitions and were generating north of $4.0bn in net sales. Berry has completed close to 15 additional acquisitions since going public and is now generating net sales of roughly $14.0bn. In aggregate, they’ve completed ~45-50 acquisitions and deployed well north of $10bn doing so.

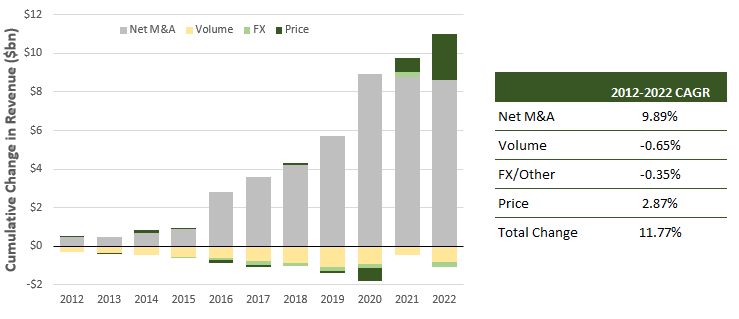

To underscore the importance of M&A I’ve broken out the cumulative change in revenue over the last decade by factor (Exhibit C). We can see that organic volume growth from 2012-2022 was actually negative and has only been offset by price in the last two years. If we ignore the last two years, organic revenue growth from 2012-2020 (volume, FX, and price) was negative 2.0%. I think there is an argument to be made that even though organic revenue growth had historically been negative, organic gross profit growth might have been flat/slightly positive – but I’ll put a pin in that for now.

Given this acquisitive history, I think it’s important to evaluate the M&A track record, determine how long the M&A runway is from here, and understand what organic gross profit growth looks like if the M&A engine is running out of steam. To help paint that picture I think it’s worth first diving into industry trends, economics of the existing business, and how scale has become a significant advantage.

Plastic Industry

The OECD estimates global plastic consumption by polymer, application, end market, and geography from 1990-2019. I’ll caveat this next section by saying that a lot of guesswork seems to go into these estimates; however, the model methodology seems reasonable, and I think it should be an acceptable data set to draw some broad conclusions from. In Exhibit D I show the OECD estimate of plastic consumption by region alongside multiple trailing CAGRs. The first thing that stands out to me is how consistent plastic consumption growth has been; since 1990, global consumption only declined in one year (2008), and it only declined by some mid-single-digit percentage.

I then plotted plastic consumption/capita (measured in kgs/year) versus real GDP/capita (2015 US$) and found that there was a consistent linear relationship between real GDP and plastic consumption (Exhibit E). When real GDP grows by 2.0%, plastic consumption tends to grow by about 2.0%.

If plastic consumption has historically tracked real GDP growth, I think it’s reasonable to ask if anything could derail that relationship in the future, and I can only thing of two reasons that plastic consumption would meaningfully lag real GDP growth: 1) lightweighting, and 2) substitution from plastics to other substrates (glass, aluminum, paper, plant-based resin, etc.).

Lightweighting is the process of making the same product with fewer kgs of plastic. There are clear environmental benefits to this, but it also makes the product cheaper. A couple of years back, Berry’s CEO made this comment (emphasis my own):

“What we find is that all of our end users have strong -- publicly communicated sustainability objectives. And so they're keen to partner with us to help understand how we can help them meet those needs. I would say still the #1 opportunity across the chain remains around weight reduction. And companies that have the design prowess and know-how to reduce the weight of substrates while not impacting physical properties, using both design and material science know-how, are going to benefit.”

Berry specifically spends about $100mn/year on R&D, largely around material science. In recent years, they’ve often talked about how they’ve reduced weight for certain product lines:

“We became the first plastic packaging manufacturer in Europe to supply the Coca-Cola company with a lightweight tethered closure for its carbonated soft drinks in PET bottles” – 1Q23

“We worked together with a leading German dairy customer, Milchwerke Schwaben, and met their sustainability needs and goals by providing a 19% weight reduced product offering” – 1Q23

“We also recently announced our launch of a new Mars jar for the well-known products such as M&M’s, Skittles, and Starburst, which will be lighter in weight” – 4Q22

“The know-how that we have in the business relative to material science is allowing that, with some converted films being lightweighted by up to 20%” – 4Q19

“And just this year, we saw several product lines lightweighted by more than 15%” –4Q19

This obviously isn’t a Berry-only phenomenon. Plenty of large competitors are doing the exact same thing, but as I’ll touch on later, this is a very fragmented industry with plenty of small plastic manufacturers that don’t have the R&D budgets to innovate meaningfully around product weight. I suspect the pressure to lightweight has also picked up in recent years as ESG concerns become more front and center, so the historical link between real GDP and global plastic consumption might already be breaking and we might just now be starting to see it. But it strikes me that the largest manufacturers that have the budgets to innovate around weight could take share from small single-plant manufacturers that can’t. So perhaps not a huge risk to the likes of Berry and large competitors like Amcor. If you recall from Exhibit C, Berry has historically reported negative organic volume growth, but they have traditionally measured volume by weight (not units). I think it’s reasonably likely that lightweighting has long been a top-line headwind for Berry (as a leader in the space), although they seem to capture some of those lightweighting savings via higher margins.

It's also worth mentioning that there are offsets to lightweighting. There are certain industries that are increasing their plastic intensity because plastic is cheaper, lighter, more versatile, and in some cases more durable than incumbent substrates (the auto and construction industries are good examples of this). There are also limits to weight reduction without compromising product quality. For example, rigid plastic bottles often get stacked when they are shipped/stored and need to have certain top load parameters to prevent the bottles from being crushed. Weight reduction can reduce top load if the bottle becomes too thin. For all these reasons, I think the risk to Berry specifically from lightweighting is probably small, even if it was a modest headwind to industry consumption as measured by weight.

On the substitution front, if we ignored ESG factors completely it would make almost no sense to switch from plastic to another substrate given the relative cost advantage of plastic. For example, Wood Mackenzie estimates that the raw material cost for an aluminum can is 25-30% higher than the raw material cost for a PET (plastic) bottle of similar volume. Similarly, glass containers tend to be more expensive to manufacture than plastic containers, are heavier and typically cost a lot more to transport, and they are more likely to break (higher waste). And then there are obvious reasons you can’t switch from plastic to something like paper (durability, water resistance, etc.). Even if these other substrates became comparable from a cost and practicality standpoint, it would take decades to build out the raw material and manufacturing capacity for a wholesale shift in substrates.

So, the main reasons to explore substitution are environmental concerns. There are legitimate concerns like plastic pollution in oceans, low recycling rates, and toxic leakage in landfills. On those fronts, plastic ranks worse than other substrates. But one thing that I think often goes overlooked is the relative carbon footprint of these different choices. McKinsey published a report last year (link) that compared the direct and indirect GHG emissions of plastic vs the next best alternative for a range of different categories. They evaluated emissions from production of raw materials, production of the product, and transportation, and found that in 13 out of 14 categories plastic had much lower GHG emissions than the next best alternative. In addition to lower GHG emissions, plastic tends have other environmental benefits like lower water consumption in the manufacturing process. I’ve read several comments from the largest consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies in the world that indicate that they understand these pros and cons. All these businesses are simultaneously looking to reduce plastic waste and emissions, which is one reason there hasn’t already been a huge push to substitute another substrate for plastic. In my view, one of the best paths forward is for the plastic industry to address the plastic waste problem – if the industry can do that effectively, then the risk of substitution diminishes.

To that last point, large plastic companies like Berry are making a big push into sustainable packaging. Berry specifically has a target for:

“100% reusable, recyclable, or compostable packaging by 2025”,

And aims to:

“increase use of circular materials by entering into offtake agreements for both mechanically recycled and advanced recycled materials and expand our own recycling operations in North America and Europe in order to meet our targeted 10% recycled content goal by 2025”.

Today, only 6-7% of total plastic production globally uses secondary (recycled) plastics. That’s up from just 1% 30 years ago, but still small in the grand scheme of things. To hit 20% or 30% will require a pretty extraordinary investment in waste management infrastructure, and that will take a long time to play out. In the meantime, the substitution debate will rage on. I think it’s reasonable to expect that this will be a modest headwind to plastic consumption growth, even when we consider the GHG emission and cost comparisons to other substrates.

Instead of underwriting industry volume growth that tracks real GDP over the next 10 years, I’d lean toward something like real GDP less 1%. But picking 1% vs 3% doesn’t really matter. Whatever the number, I feel very confident that the tonnes of plastic being consumed a decade from now will be more than what’s being consumed today – even in developed countries with lower real GDP growth. Against that backdrop, I suspect unit volumes being produced by large manufacturers like Berry will remain relatively stable over time. Reasonable pushback to that last statement might be that industry plastic consumption has increased at some low single-digit rate while Berry’s organic volume growth was negative - what gives? I think part of the explanation is lightweighting, but I think the bigger reason is that Berry frequently “rationalizes” facilities following acquisitions - effectively trading off volume for higher margins. If they stopped aggressively pursuing M&A, I’d expect that there would be fewer (or no) rationalizations going forward, and true run-rate organic volume growth should be much closer to industry averages. I’ll come back to this point later.

Economics of the existing business

Raw hydrocarbon streams like oil and natural gas get produced and sent to a refinery, gas plant, or fractionation facility where the single input is separated into a variety of refined products. Two of those refined products are ethane and propane, which in turn get turned into ethylene and propylene. Large chemical producers like Dow Chemical, Lyondell Basel, Exxon Mobil, SABIC, and BASF will then take the gaseous ethylene and propylene, run it through a very complicated polymerization process, and produce solid pellets of polyethylene and polypropylene. These solid pellets are some of the most common inputs to the plastic manufacturing process. They can be easily transported, melted down, and reformed into finished products. Technically, polymerized ethylene and propylene are the building blocks for >50% of all plastics produced in the world (and something close to 90% of all plastic produced by BERY), but plenty of other raw inputs like butylene can also be polymerized and used to create a wide range of products with unique properties. As a category, BERY refers to these core inputs to the plastic manufacturing process as polymer resins.

Ultimately, resin prices fluctuate with the price of the raw commodity, but plastic manufacturers like Berry enter into agreements with customers that allow them to pass-through changes in price. If resin prices increased 50% (like we saw from mid-2020 to mid-2022), all that raw input cost inflation gets reflected in higher selling prices. That’s a big deal for the manufacturers considering that polymer resin makes up 50%+ of COGS (call it 40% of revenue) – without this pass-through mechanism, margins would be extremely volatile. It looks like packaging typically represents 5-10% of the final product price, so even if resin prices increase by 50%, the ultimate impact to Berry’s customers would only be a 1-2% increase in their COGS.

Unfortunately, Berry doesn’t explicitly break out expenses line-by-line, but Exhibit F shows a rough breakdown of what the expense/margin profile looks like based on my research. Resin is the vast majority of materials purchases (90%+), where the next largest expense is direct labor at manufacturing facilities, followed by energy and transportation costs.

I think it’s reasonable to expect that run-rate EBITDA margins are somewhere in the 17% range, which is roughly what Berry put up between 2015 and 2020 (Exhibit G). EBITDA margins expanded meaningfully between 2007 and 2015, which I believe is largely a function of increased scale and higher margins from lightweighting. Most recently, EBITDA margins have compressed, and 2022 margins were lower than at any point since 2014. One reason for margin compression is that resin prices increased significantly and that was passed on to customers via higher prices/revenue. All else equal, that would lead to lower margins but flat EBITDA. And yet, adjusted EBITDA dollars were down slightly from 2020-2022 (even after stripping out the impact of dispositions/FX), which tells me that something else contributed to lower margins/higher absolute expenses.

Margin compression is never great to see, but I’m inclined to believe that that the worst of it is behind us (famous last words, right?). For starters, electricity prices have gone gangbusters over the last two years. Benchmark electricity prices in some European countries had quintupled from mid-2020 to mid-2022! Even in North America, electricity prices have increased considerably. The same goes for transport costs and wages. One Tegus expert pointed out that when Berry signs multi-year contracts with large customers only the materials component has a pass-through mechanism (even then, there appears to be a 1–3-month lag). If there is unexpected inflation in any of the other expense lines, Berry eats that added cost for the duration of the contract. In extreme cases, I’m sure Berry renegotiates, but it’s difficult to imagine going to the negotiating table with Coca-Cola and asking for better pricing instead of eating the higher expenses for a couple years. As such, I think it’s reasonable to assume that margins will compress when non-material expenses inflate rapidly. Contracts eventually roll over and new prices get negotiated based on the prevailing cost environment, and I suspect Berry will claw back margin over the next 2 years. Berry’s CFO and CEO have mentioned multiple times in recent quarters that there is a lag to inflation recovery, but that they are starting to see that now and expect continued inflation recovery through 2023 (specifically in the second half of the year).

In Exhibit H I show the historical relationship between y/y change in gross margin vs y/y U.S. CPI (as a proxy for Berry’s non-material inflation). Prior to 2021, there was a strong linear relationship between change in margins and a small change in inflation – margins expanded when inflation came in low and vice versa. We can also see that margins compressed significantly as inflation rapidly accelerated in mid-2021, but after having a few quarters for contracts to roll over and inflation peaking, margins turned a corner. Both gross margins and EBITDA margins troughed in 1Q22 and have generally improved since, which supports the view that there is indeed a lag to inflation recovery outside of resin.

It's also worth pointing out that Berry has undergone several cost reduction initiatives recently that should lead to improving margins in 2023.

“We’ve made in the last 3 years alone over $250 million in capital improvements to remove over 5 million labor hours from our operations through deploying more automation... We’ve invested over $100mn to remove over 200 million kilowatt hours from our operations.”

To put those comments in perspective, if Berry removed 5 million labor hours at $20/hour, that’s a $100mn reduction in direct labor costs, which gets partially offset by some incremental energy costs. Similarly, removing 200mn kilowatt hours at $0.20/kwh would be another $40mn reduction in COGS. Berry last guided to $125mn of improving profit dollars in 2023 (if volumes stayed flat) where $100mn was from cost reduction initiatives and $25mn was from inflation recovery. In aggregate, that’s effectively a 1% improvement in margin y/y (5-6% improvement in absolute EBITDA), with what I would expect to be more inflation recovery in 2024.

All told, I think we’ve seen margins trough, and I think there are clear reasons to expect both margins and absolute EBITDA to start improving modestly in the near future.

The other important dynamic to think about is how much capital Berry has to deploy to generate those EBITDA dollars. Unfortunately, plastic manufacturing is a capital-intensive endeavor, where 25-30% of EBITDA is reinvested just to maintain the existing business. The gross value of PP&E is north of $8.0bn, where most of that is investments in manufacturing equipment with an average useful life of about 15 years. As a result, Berry spends $500-600mn/year just to stand still (they’ve long argued that maintenance capex is just $300-350mn, but for the life of me I can’t get there). Despite the high capital intensity, this is a surprisingly profitable operation. Core ROIC at the asset level (see the note in Exhibit I) ebbs and flows with the equipment replacement cycle but averaged 20% from 2010-2022. Since Berry acquired most of their existing facilities and paid more than the value of fixed tangible assets, their actual ROIC would be much lower. Even still, I think this provides a good framework for thinking about incremental organic returns. If they never pursued M&A again, I think it would be reasonable to expect that incremental returns would be in this range. Berry’s management team has repeatedly stated that they see incremental organic returns in the 20% range, which is consistent with historical data.

Despite core ROIC being quite strong, it doesn’t look like Berry’s organic reinvestment rate is very high. In fact, Exhibit J shows a time series of capex over depreciation, and up until quite recently it looks like Berry had actually been underinvesting in their business. It’s likely that high capex from 2020-2022 was just part of the replacement cycle and isn’t adding meaningful net new capacity. As an investor, I think it’s reasonable to look at this and be concerned about organic growth. As I flagged earlier, organic revenue growth had historically been negative, and as I’ll touch on shortly, organic gross profit growth is probably roundable to 0% (or very low +ive single digits). So, who cares if core ROIC is high if organic reinvestment opportunities are few and far between?

One reason why organic reinvestment might have been low historically is that Berry focused so much energy on rolling up other plastic manufacturers. If M&A slows down in the future, will attention shift to organic growth? Even if it did, unit growth for this industry is some low-single-digit percentage, so it’s not like reinvestment opportunities are growing on trees.

Overall, I think it’s pretty clear that Berry has a profitable, stable, and relatively predictable existing business. There is probably some upside to margins/absolute EBITDA in the near term as cost reduction initiatives and inflation recovery takes hold, but I personally wouldn’t underwrite much organic growth in a base case beyond that. And that’s totally fine if you aren’t paying for it.

So that leaves us with M&A as the primary growth lever. Before jumping down that rabbit hole, the final thing worth exploring is why scale matters as a competitive advantage.

Scale – Berry’s one competitive advantage

Scale matters for several reasons, but perhaps the most important is that it gives Berry some purchasing power for raw materials. By my estimate, Berry purchases around 5.0mn tons of resin per year – specifically polypropylene and polyethylene. That’s close to 2% of all the polypropylene and polyethylene produced on the planet, and probably in the order of 5-6% of all the polypropylene and polyethylene produced in North America and Europe. The chemical industry that produces these resins is pretty concentrated, but I suspect Berry is typically the largest (or second largest) buyer of resins from any given chemical plant that they purchase from. One Tegus expert noted that it was typical for a resin purchaser to get a 1% discount for each metric ton that they purchase/month. I’ve seen multiple references that indicate Berry receives close to a 10% discount to index resin prices on average, which make sense considering they’re buying 400k+ tons of resin/month from lots of suppliers all over the world. That’s a big deal when you consider resin purchases make up ~40% of revenue. If Berry kept 100% of that discount, that would improve their margins by 4% and ROIC by 5%. I can’t prove it, but I suspect that Berry passes a lot of that discount on to some of their largest accounts like Proctor & Gamble and Coca-Cola, but recall that the top 10 customers account for just 15% of revenue and Berry serves more than 10,000 customers globally. For that long tail of small customers, I suspect that Berry keeps most of that discount for themselves.

That resin discount dynamic isn’t unique to Berry. All big competitors would receive similar benefits. The thing is, there just isn’t that many large competitors. If we start with the assumption that Berry has a 2% global share – representative of their share of global polyethylene and polypropylene purchases – then the top 10 public competitors look to have about 8% market share. Number 10 on that list would come in at a measly 0.1%. I haven’t looked at the geographic splits of those top 10 competitors, but even if we assumed it was 100% North America/Europe, the top 10 would have just 20% share and number 10 on that list would be just 0.3%. When I Googled plastic manufacturers in the small Canadian city that I live in, more than a dozen local options popped up. For the most part these seem to be very small businesses that specialize in making just a handful of related products out of a single facility. Berry itself is just a collection of what used to largely be ~40-45 small independent plastic manufacturers – they have made a few large acquisitions, but they’ve also purchased businesses for as little as $20mn.

In my view, you can probably count on two hands how many competitors are receiving volume discounts on resin anywhere near what Berry realizes. The industry also appears fragmented enough that even if the largest purchasers continue consolidating the industry would still be very fragmented for decades. If that’s true, then Berry and other large competitors are likely to continue enjoying higher than average margins on the back of resin discounts for a long time.

Unfortunately, it’s not easy to parse through other packaging company margins and create an apples-to-apples comparison to measure the magnitude of this competitive advantage. Many of the competitors manufacture products outside of plastics (like glass, aluminum, paper), and even within plastics there are proportional differences between more commoditized and specialty offerings which makes margin comparisons tricky (Berry leans more toward commoditized products which tend to be lower margin). In any event, Exhibit K shows Berry’s margins vs those of the broader packaging universe (including businesses that do metal, glass, and paper manufacturing), and Berry tends to come in around the top 30th percentile. As an aside, I find it remarkable how resilient margins tend to be through the cycle for this comp group. I wouldn’t go so far as to say these are recession-proof businesses, but they are certainly recession-resistant.

Resin discounts aren’t the only scale benefits that Berry enjoys.

Many CPG products have multiple plastic components. For example, L’Oreal or Proctor and Gamble might require a bottle, closure, pump, and tube to assemble a dispensable soap. Small manufacturers can’t make every single component themselves, but Berry can do it all. They can source an entire product line, which is compelling for large buyers. Once Berry is making an entire product line, I suspect that customer is unlikely to switch to another manufacturer or multiple manufacturers. One reason is that large CPG customers tend to require custom molds, which are the inserts that go into the machine and determine the shape of the final product. Those custom molds are expensive to make, and most plastic manufacturers require that customers using custom molds sign multi-year contracts and pay for that mold investment via higher unit prices during the contract term. Even once the contract rolls off and the custom mold is amortized, that CPG customer can continue using a paid-for mold (which Berry owns), or switch manufacturing partners and have to pay for the molds all over again. In my view, it rarely makes sense to do that, so any given product line using custom molds should be relatively sticky.

Similarly, Berry has some of the highest volume equipment in the market. For example, a German company called Reicofil seems to be the dominant machine supplier for some HHS lines globally. They started making commercial machines in 1992 and have since rolled out multiple generations of that first machine. The fifth (and latest) generation Reicofil can process 7x more unit volume than some of the earlier generations being used in industry today, but a single fifth generation line can cost almost $100mn! I think there are only a couple hundred fifth generation lines installed in the world, and I’d bet that the long tail of small competitors don’t own any of them. These large capital investments ultimately reduce the unit cost of production, which puts small manufacturers at a disadvantage and makes it difficult for them to steal high-volume business from the large incumbents.

Berry also has more than 250 manufacturing facilities around the world, which gives them a lot of flexibility to “optimize transportation costs and realize distribution efficiencies”. Some plastic products are really inefficient to transport long distances. For example, bottles don’t weigh a lot and can’t be stacked like pales, so you end up shipping very little weight and a lot of air. So having hundreds of distributed facilities should lead to reduced transportation costs at the margin if Berry can shift volumes effectively between plants.

Finally, as sustainability becomes more important, the scaled players like Berry are well positioned to take share. There are all the obvious benefits of having large R&D budgets and innovating around material science like I mentioned earlier, but then there are some nuanced advantages that large competitors have. For example, there is always scrap from the plastic production process, and that scrap can be recycled (melted down and used in another run). Some newer (expensive) machines automatically collect and feed scrap back into the run, but often that “regrind” has to get used for other products. Most products have specifications that require XYZ% of virgin material (often 70-90%), and specifications for what type of regrind can get used. If scrap has a lot of additives and colors, it can’t typically be used for food and beverage or hygiene packaging and must get diverted into industrial products. It’s cost prohibitive to “ship regrind from California to Kentucky”, so if you don’t have an industrial facility near an HHS facility then it would be tough to find internal uses for second hand resin. From that perspective, companies like Berry with a large manufacturing footprint are better positioned to internally recycle regrind, which I suspect leads to a modest cost advantage as more products use recycled materials.

Unfortunately, most of what I’ve just highlighted differentiates Berry vs small competitors but doesn’t give Berry an edge over another plastic behemoth like Amcor. So, while I think scale does matter at the margin, it’s hard to argue that Berry has some impenetrable moat. When a small competitor places an order for a few thousand units, Berry can probably capture some excess return. But when L’Oreal evaluates manufacturing options, they’re going to get Berry and their large competitors to all compete on price, and that puts a ceiling on margins even with these benefits of scale.

Where scale can still make a big difference is acquisition synergies, and that’s a good segue into M&A.

M&A

As I’ve already illustrated, M&A has been the main contributor to Berry’s top-line and bottom-line growth over the last decade. They’ve made half a dozen small acquisitions (<$100m), half a dozen medium-sized acquisitions ($100-800mn) and two multi-billion-dollar acquisitions.

For most of those smaller deals, the obvious strategy is to acquire the business and immediately realize resin purchasing synergies. For example, in late-2017 Berry acquired Clopay for $475mn. Clopay generated $461mn of revenue and $53mn of EBITDA in 2017, which translates into an EBITDA margin of 11.5% and initial EV/EBITDA purchase multiple of 9.0x. A former Clopay employee noted that after the Berry acquisition they started buying resin at significant discounts – something in the realm of 10%. If nothing else changed, that would improve EBITDA margins from 11.5% to 15.5%, and take the post-revenue-synergy purchase multiple down to 6.6x EV/EBITDA.

Historically, Berry also realizes operational efficiencies after “rationalizing” facilities. For example, in 2011 they shut down 6 facilities and moved the majority of those operations to other plants. They had increased “price to improve product profitability in markets with historically low margins”, which led to lower volumes but higher gross margins (arguably flat or slightly positive gross profit dollars). Similarly, in 2016 (after the $2.3bn AVINTIV acquisition) they shifted assets toward higher margin but lower volume products. They seem to do this almost every year as they acquire new facilities and find ways to generate more gross profit dollars from the same footprint. In addition to all these actions that lead to higher gross margins, there are also the standard SG&A synergies that contribute to EBITDA margin expansion. I’ve shown SG&A and COGS (ex. DD&A) as a percentage of revenue over time in Exhibit L, and we can see that there is evidence of margin expansion on both front. Obviously 2021/2022 were odd years for reasons I already highlighted, and both SG&A and COGS as a % of revenue tend to temporarily increase around big deals (2015/2019), but the trend for both line items is clear. I think it’s reasonable to expect that rationalization opportunities and SG&A synergies add some additional margin benefits to acquired entities.

As an aside, you’ll recall from Exhibit C that organic revenue growth had historically been modestly negative (prior to 2021/2022). But that can be misleading. The strategy of rationalizing and optimizing facilities for higher margin but lower volume products would clearly lead to organic gross profit/EBITDA growth that’s higher than organic revenue growth. The same can be said when Berry reduces product weight but captures higher margins. I indexed revenue, gross profit, and adj. EBITDA to 1 in 2007 and then tracked the cumulative change of all three over time (Exhibit M). We can see that underlying profit growth outpaced revenue growth. Looked at through this lens, I think you can argue that Berry has modestly positive organic profit growth despite the negative organic revenue growth. If M&A becomes a less important part of the strategy going forward, I suspect we’ll see organic revenue and profit growth converge.

Circling back to the Clopay acquisition… if we just include the resin-purchasing synergies, shave off depreciation (which on average should = maintenance capex) and taxes, and then add back the tax shield from amortization of acquired intangibles, then the FCFF cash yield on that deal would have been ~9-10%. Layer in some debt at their target leverage range and the prevailing interest rate at the time, and the FCFE cash yield would have been closer to 15%. Their levered a-tax IRR should be slightly higher than that FCFE cash yield, which would be a reasonably healthy spread over their cost of equity. Without the resin discount, I estimate that the FCFE cash yield would be more like 8%. Sure, the other cost synergies (maybe 1% of revenue) would help at the margin, but they pale in comparison to the resin uplift. In my view, the primary reason that incremental returns from small M&A can end up being almost twice their cost of capital is the resin discount.

Of the ~$10bn in acquisitions completed over the last decade, roughly 20% were businesses in a similar snack bracket as Clopay where Berry could realize significant resin synergies. The other 80% of capital deployed on M&A was on two multi-billion-dollar deals: AVINTIV, for $2.3bn in calendar 2015 and RPC for ~$6.5bn in 2019. Berry’s management explicitly stated that they expect synergies on those large deals to be less than synergies on small M&A, and I suspect that’s because these large targets were already receiving significant resin discounts. Even still, on the RPC acquisition, Berry seems to indicate that they exceeded $150mn of synergies on a business that was generating ~$800mn in EBITDA pre-close – 50% on procurement, 30% G&A, and 20% from operational improvements. That would take the RPC deal to 7.1x EV/EBITDA post-synergies from 8.4x pre-synergies (a much smaller improvement than Clopay). That would ultimately translate to an 8% FCFF cash yield and a 12% FCFE cash yield at their target leverage range. That’s nothing to write home about, but still a modestly better alternative to returning capital to shareholders over any long period of time.

In Exhibit N I show ROIC for the underlying assets (if these businesses had been built out organically) and Berry’s actual ROIC, where the difference comes about because of the price Berry pays for those underlying assets (all the goodwill and intangibles). Berry’s historical actual ROIC of ~9-10% lines up with my FCFF estimate on some of the individual deals of 8-10%. Looked at through this lens, I think there is a good argument to be made that Berry should focus more energy on organic growth, even though M&A has added some value to shareholders in the past.

To the last point above, Berry’s management team has explicitly stated that they are done with large M&A like the RPC and AVINTIV deals. When it comes to reinvestment, they’ll now be focused on some combination of organic growth and bolt-on acquisitions. That should lead to improving overall returns given bolt-on acquisitions seem to generate a better ROIC than large deals, and organic initiatives generate returns that are nearly 2x higher than acquisitions. They have some near-term capital allocation priorities that take precedence to bolt-on acquisitions, but I suspect we’ll start to see that pick up again in a couple years.

It's hard to estimate what the bolt-on acquisition opportunity set looks like. That being said, we do know that this is a very fragmented industry, and I’d guess that there are hundreds, if not thousands of potential targets globally. Could Berry complete one small acquisition for $100mn every year? Probably. But now that Berry is generating $800mn+ of FCFE, that’s only a 10-15% reinvestment rate. At a 15% reinvestment rate and 15% incremental a-tax levered IRR, you’re looking at a 2.25% inorganic growth rate. I personally hold the view that this is a mature business in a mature industry, and incremental growth from here will be much lower than it has been historically. And that’s totally fine. As it stands today, I think Berry can start to return significant capital to shareholders, which is not something they’ve done historically. I’ll circle back on what this could look like in the valuation section.

Balance Sheet

Unsurprisingly, Berry had a heavy debt load when Apollo and their partners took the business public. Despite debt increasing in absolute dollars to help fund acquisitions, ND/EBITDA has steadily improved over the last decade. I’ve shown a time series of ND/EBITDA in Exhibit O and we can see that leverage is lower today than at any point since 2012.

Despite leverage improving materially, Berry still carries proportionally more debt than any of the other packaging businesses in the comp group (Exhibit P). They recently put out a target ND/EBITDA range of 2.5-3.5x, which is a little lower than where they sit today but would still be at the high end of the comp group. Even with some modest EBITDA growth, it’s likely that Berry will have to use some FCFE to retire debt in the next couple years to get into the middle of that target range.

Regardless of how I slice it, Berry is trading at a discount to the comp group, and I suspect one of the primary reasons is a perceived leverage problem. I think it’s been well established that Berry’s business would hold up very well in a recession, so I don’t think there are any valid liquidity concerns. The bigger problem seems to be that the effective interest rate that Berry is paying today could increase significantly as some of their legacy fixed-rate debt matures and hedges expire, which would put a meaningful dent in FCFE.

In Exhibit Q I show Berry’s historical interest expense in dollars and as a percentage of outstanding debt. Last year, they paid just ~3.0% on their outstanding debt balance. That’s largely because they issued a series of notes at <2.0% in the last two years and hedged a significant chunk of their floating rate exposure. Those low-cost notes and hedges mostly roll off by the end of 2026. Last month Berry issued $500mn of new notes at 5.5% (largely to replace some low-cost debt that matures next year). If all their debt repriced at 5.5%, their annual interest expense would go up by $230mn relative to 2022 (call it $180mn after the tax shield). For 2023, Berry is guiding to ~$800mn of FCFE, so that incremental interest expense would whittle down FCFE by a whopping 23%. We still have a few years before most of their debt reprices, but this is certainly a dynamic to be cognizant of when thinking about valuation. I also think that’s one reason Berry is planning to continue reducing leverage in the medium term.

Management and Governance

In February, 2020 Canyon Capital owned 7% of Berry’s outstanding shares and wrote an open letter to Berry about capital allocation (you can find it here). In November, 2021 a smaller shareholder called Ancora Holdings wrote a second open letter echoing similar concerns (you can find that one here).

Both Canyon and Ancora pointed out that Berry’s total shareholder return (TSR) had lagged the peer group and broader market, and that Berry was trading at a significant discount to their peer group on a range of different metrics (EV/EBITDA, FCF yield, etc.). Canyon specifically called for more aggressive deleveraging aided by divestitures and better ESG communication to combat the negative perception of plastic as a substrate. While the Canyon letter was a textbook compliment sandwich, Ancora’s letter was much more aggressive. Ancora criticized the Board for not using FCF to repurchase shares at what they viewed as an attractive discount to fair value and suggested that Berry expand their repurchase authorization to $1.0bn. They also called on Berry to monetize real estate assets (sale-leasebacks), evaluate a go-private transaction, and halt all M&A.

Since those letters were written, Berry has sold ~$300mn of assets, repurchased nearly $900mn of stock (as of 1Q23), instituted a small dividend, and deleveraged modestly. Despite some of that progress, Ancora and yet another investor – Eminence Capital – continued to engage with the Board and ended up signing a “Cooperation Agreement” in November 2022. As part of that agreement, Ancora and Eminence each appointed a director to the Board and Berry formed a new Capital Allocation Committee. One of those appointments was a partner from Canyon Capital, and the other was the former Chairman/CEO of Ferro Corporation. Both of those newly appointed directors will sit on the Capital Allocation Committee.

In Exhibit R I show Berry’s historical sources/uses of cash over the last decade (ending 2022). We can see that >100% of CFO was directed toward capex/M&A, and that almost no capital was returned to shareholders until recently. Given the changes to the Board, the new Capital Allocation Committee, and the internal view that Berry stock is trading at a significant discount to fair value, I think it’s fair to expect that Berry will direct a significant portion of their FCF to buybacks so long as that discount persists. I also suspect that Berry will continue to sell some small non-core assets, reduce absolute debt, and spend a very small percentage of their FCF on bolt-on acquisitions. That’s a significant change to their historical capital allocation approach.

It might be coincidence, but shortly after these Board changes, Berry’s CEO (Thomas Salmon) announced his intention to retire atr the end of 2023. Thomas Salmon joined Berry in 2003 and has been the CEO since 2017. During his reign as CEO, Berry acquired RPC and three other plastic businesses, and grew revenue, EBITDA, and EPS by 104%, 63%, and 119% respectively (to be fair, outstanding debt balances nearly doubled as well). Now that meaningful M&A is in the rearview mirror and Berry is pivoting to a capital return/deleveraging story, I think it’s safe to assume that the CEO seat has lost its luster for Thomas. As I write this, Berry is actively searching for his replacement, but we don’t yet know what that’ll look like. Given what is bound to be a low organic reinvestment rate, and a new Capital Allocation Committee that is prioritizing capital returns, I think the importance of the CEO role to business success over the next 5 years has diminished. As such, I’m not too concerned about who the next CEO will be, but suspect they’ll look for someone who can reignite organic growth.

Berry’s incentive plan for NEOs seems standard. More than 60% of total comp comes from the LTIP which is a 50/50 split of options and PSUs, where the PSUs vest based on a combination of relative TSR and ROCE targets. Inside ownership has historically been reasonable relative to total compensation, but cumulatively all NEOs and directors own just 2.8% of outstanding shares (1.7% outside of Thomas). There were one or two small things that didn’t sit well with me after flipping through the latest proxy statement, like an agreement that allowed Thomas personal use of Berry’s aircraft (that benefit was valued at $313k in 2022 vs a base salary of $1.2mn). Aside from that, I don’t think there are any perverse incentives in the plan and the incentive structure/alignment looks par for the course amongst large public companies. Not great, but not horrible.

If it wasn’t for the intervention of Canyon, Ancora, and Eminence, I’m not sure if this management team/board would have pivoted from acquisitions to capital returns/deleveraging as aggressively as they are now. But given the recent changes I think we have pretty good visibility into what to expect for capital allocation over the next 5+ years. I haven’t seen an explicit comment about how Berry ranks capital allocation options, but Thomas did make reference to the fact that they are prioritizing buybacks over deleveraging (and other options) because there was a:

“compelling opportunity to repurchase our shares right now, given the dislocation in our valuation takes precedence. We believe it is an unmatched opportunity for us. So we’re going to continue to focus on buying back our shares as part of our capital allocation program in ‘23. And certainly, as we see improvement in the valuation of those shares, we can ultimately pivot further to debt reduction”

Comments like that lead me to believe that the new Capital Allocation Committee will be thoughtful about where they direct dollars, and could easily pivot back to bolt-on acquisitions or deleveraging if the expected return from repurchases falls (share price increases).

What is the market pricing in?

To help understand what the market might be pricing in, I came up with a set of assumptions for key drivers in my DCF model that got fair value to approximate the current share price. Those implied expectations were shockingly punitive.

For starters, I had to assume that revenue organically fell by 15% over the next two years and then was flat into perpetuity. Let’s say the near-term decline is largely just normalization of resin prices leading to lower pass-through expenses. That would take Berry to run-rate revenue in 2024 that’s roughly in-line with what they generated in 2020, or ~no organic growth from 2020-2024. Beyond 2024, there would be some revenue upside from normal inflation, so implicitly this assumes a 2-3% annual decline in unit volume. Given the historical linkage between real GDP growth and plastic consumption, the only way this would be possible is if A) Berry lost market share, B) there is significant global substitution from plastic to other substrates, or C) lightweighting continues to be a perpetual drag on volume.

Organic volume growth has historically been negative (call it 1-2%) as measured by weight. But as I’ve outlined before, it’s likely that Berry was lightweighting products and splitting those cost savings with customers – hence some of the historical margin improvement. But to back into the current price, I also had to assume that run-rate margins are structurally lower in the future than the last 5-10 years (Exhibit T). So, if volume declines implied by the revenue assumptions were because of lightweighting, this would be an extremely punitive margin assumption. I don’t think it’s likely that Berry loses share, so to underwrite volume declines and lower margins you’d have to believe that other substrates were going to take significant share from plastic. That’s not an impossible position to defend, but it’s certainly not what I’d underwrite in a base case given some of the plastic advantages I outlined in the industry section and the steps being taken by the industry to address environmental concerns.

Using these assumptions, I get a ~10% decline in adjusted EBTIDA from 2022-2024, where 2024 adjusted EBITDA is just $1.9bn vs 2023 guidance of $2.05-2.15bn. And then EBITDA stays there… forever. In effect, we have to assume that organic growth is 0% into perpetuity and Berry does exactly nil accretive M&A.

I then have to assume that Berry repays $3.8bn of debt over the next decade to reduce ND/EBITDA into the mid-2x range. That debt repayment soaks up 50% of their FCFE over the next decade. Even with that debt repayment, I assume that all their remaining debt gets repriced at ~6.00% within a few years, and Berry’s interest expense in absolute dollars ends up being 20% higher than what they paid in 2022 (on a much lower debt balance).

With declining EBITDA and higher interest expense, cash flow from operations falls by 17% through 2027, and then plateaus thereafter. I then assume that Berry spends about $600mn/year on maintenance capex (consistent with guidance for total capex this year) despite perpetually declining volumes. The net effect is that free cash flow to equity (before debt repayments) falls to $700mn by 2027.

Even with these assumptions, my model suggests that Berry could repurchase $3.5bn of their shares and pay nearly $1.1bn in dividends over the next decade. That’s $4.6bn of capital returns on a current market cap (using fully diluted shares) of $7.9bn.

In the DCF model I use a 9.0% cost of equity, 6.0% cost of debt, 10% terminal ROIC, and 0% terminal growth rate. Using these assumptions, the implied terminal multiples are ~11x P/E and 7.0x EV/EBITDA – roughly in-line with where Berry trades today.

Personally, I’d be surprised if this scenario played out. What’s wild, is that even if this turned out to be an accurate portrayal of the future, an investor at today’s price should still expect to generate a 9.0% return! I would comfortably take the over on these assumptions, and expect a much higher return than 9.0%, which brings us to my base case.

Base Case

In the base case I came up with a set of assumptions that I feel reasonably comfortable underwriting.

There are several reasons to expect that 2023 could be weaker than 2022 from a top line perspective, like volumes from their more cyclical businesses eroding (or resin price simply normalizing). Offsetting that are some positive margin tailwinds like inflation recovery and the cost saving initiatives I outlined earlier. Taken together, I feel comfortable underwriting the low end of EBITDA guidance ($2.05bn) for 2023, which is ~1.5% lower than 2022. Beyond that, I’ve settled on ~3% revenue growth for the forecast period. As Berry starts to focus on organic growth instead of M&A (no more rationalizations), I feel reasonably confident that they can hold volumes flat even with continued lightweighting, particularly as they look to expand outside of North America and Europe where real GDP growth is higher (like the new HHS facility in India). Layer in inflation, and viola… 3%. I ultimately have EBITDA margins getting back to 16.25%, which is in-line with the T5Y average, but lower than the 2016-2020 average of 17.4%. The net result is an adjusted EBITDA CAGR of 2.3% from 2022-2032. Hardly a stretch. Notably, I’m not willing to underwrite any incremental M&A, but that’s certainly on the table as well. In Exhibit X I show my revenue, EBITDA margin, and absolute EBITDA assumptions for the base case.

To deliver on that EBITDA growth I have Berry’s net reinvestment rate at 15-20% (capex is higher than depreciation by 15-20%). Implicitly, that works out to about a 20% incremental ROIC for organic projects, which is consistent with historical ROIC at the asset level that I showed in Exhibit I.

With modest EBITDA growth, Berry naturally deleverages, but I still have them paying down about $2.0bn of debt over time, which brings ND/EBITDA into the mid-2.0x range (closer to the peer group average). I still assume that debt reprices at 6.0% once some of the existing notes and hedges mature in 2026, so absolute interest payments still increase by almost 60% from 2022.

With these assumptions in the base case, cash flow from operations ends up being relatively flat over the next decade, while free cash flow to equity (excluding debt repayments) falls modestly on higher growth capex and higher interest expense.

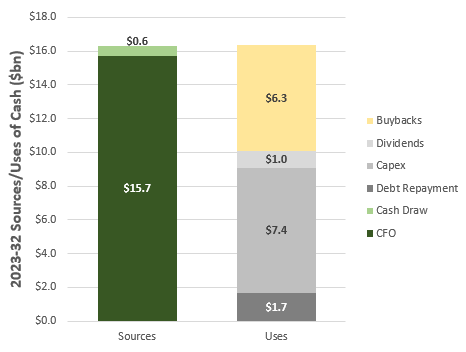

Even with free cash flow to equity declining modestly, Berry can return a significant amount of capital to shareholders. Exhibit AA shows my sources and uses of cash in the base case, and with these assumptions Berry could return more than $7.0bn of capital to shareholders over the next decade even while they deleverage to the low end of their target range and continue to reinvest in their business. If Berry’s share price increased by 8%/year for the next decade (from $57/share), they’d end up repurchasing a little more than 60% of outstanding shares.

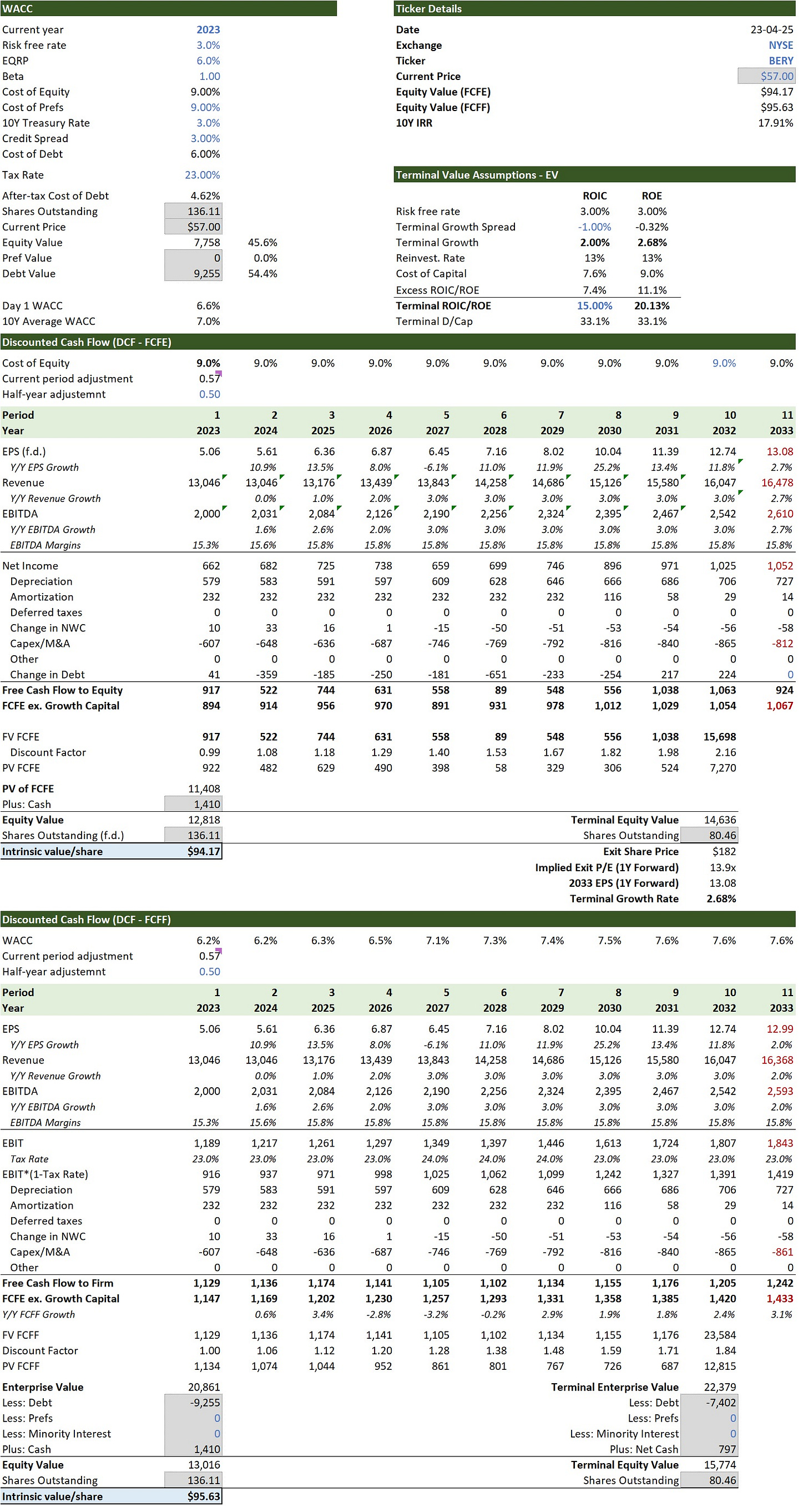

In the DCF model I use a 9.0% cost of equity, 6.0% cost of debt, 15% terminal ROIC, and 2% terminal growth rate. Using these assumptions, the implied terminal multiples are ~14x P/E and 8.6x EV/EBITDA. Fair value in my base case is ~$95/share, which is 67% higher than the current share price and suggests a 10Y IRR of ~18%.

The model essentially assumes that Berry repurchases shares at fair value (their 9% cost of equity). With these assumptions, that’s $95/share. But if Berry can repurchase 20% of their float at the current price, that ends up being very accretive to remaining shareholders – I roughly estimate that this would add $15+/share to fair value.

You can play around with my assumptions in the model (see below), but I’ve also included a snapshot of my DCF output tab in Exhibit AB.

Conclusion

No doubt about it, Berry is a boring business and operates in a mature industry. ROIC at the asset level is solid even with the high capital intensity, but there doesn’t appear to be significant organic reinvestment opportunities. They are also grappling with high leverage, and interest costs that are bound to reprice higher and eat into FCFE. Scale is their only real competitive advantage, but even then, it doesn’t differentiate Berry vs other large competitors like Amcor. I can also sympathize with investors that are concerned about lightweighting and substitution risk for the industry overall, although I generally feel like those concerns are overblown.

On the other hand, plastic volumes have proven to be relatively stable through the cycle, and Berry in particular serves end markets that should be even more resilient. Over any rolling 3-year period this business should also be able to pass through inflation to end consumers, which leads to more predictable margins than I would have guessed when I started my research. Outside of changing interest costs, I think FCFE from the existing business should therefore be relatively consistent over time. The current FCFE yield is ~11-12% (after growth capex), and with the new Board members and Capital Allocation Committee, Berry is very well positioned to take that FCFE and repurchase shares at what I view as a large discount to fair value.

In my view, expectations for key drivers implied by the current price are overly punitive, and the risk of permanent capital impairment looks low. As an investor, you don’t need to assume a lot to generate a high-teens 10Y IRR, and that’s before giving them credit for accretive buybacks or bolt-on acquisitions. Given what I view as an attractive risk/reward, I’ve recently become a Berry shareholder.

As always, if you have any pushback, comments, or questions I encourage you to reach out. You can comment below, find me on Twitter, or reach me at the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

This deep dive and included model is great, thanks for putting this up on substack! A few comments, questions (please forgive anything stupid here):

Your IRR is 18%, but annualized return of stock price from $55 to $182 is 12.7%, add maybe 1% for dividends, and you arrive at 14% annualized. Do you think 18% return overstates the buy case here? Please correct me if I have this wrong.

Are you concerned that management will grant large numbers of shares to themselves over the next 10 years? I think even just granting options and RSUs they have authorized (about ~15M) would negate most of the effects of repurchase you built into the model.

Thanks for the great write up. One question I had is whether falling oil and natural gas prices (as we are seeing at the moment) are in incremental positive for BERY? I guess that might be somewhat countered by the fact that the oil price falling is signalling falling demand and recession, but in isolation lower oil and gas prices lower input costs so are a good thing I think?