CSU is at it again with another spin-out. This time, it will be a collection of VMS businesses focused on a handful of specific verticals rather than on a specific geography (like TOI was). This new entity will be called Lumine, and in conjunction with the spin-out it will be completing the acquisition of a large VMS business called WideOrbit. In this deep-dive I’ll explore the legacy Lumine portfolio and the new WideOrbit business separately, and then look at what the pro forma entity might be capable of, how it’s governed, and what the ownership structure looks like. Finally, I’ve included my base case valuation work and sensitivity/scenario analysis with the hope of providing investors with some goalposts to think about when Lumine starts trading.

I won’t rehash some of the competitive advantages that make CSU so exceptional like their decentralized organizational structure, culture, and the magic of small VMS businesses. In my view, the pro forma Lumine entity will embody most of these traits, and throughout this piece I’m working under the assumption that the reader is well versed on that front. If you’re new to the story or need a refresher, I’d refer you to my original CSU deep-dive that was posted two years ago (you can find it here).

As always, I encourage you to reach out if you have feedback, questions, or would like to challenge any of my assumptions. I can be reached at the10thmanbb@gmail.com, in the comments below, or on Twitter.

Disclosure: I own CSU, and will end up becoming a Lumine shareholder by default when it gets spun out.

Legacy Lumine Portfolio

Volaris is an Operating Group (OG) within Constellation Software (CSU), and I believe they manage somewhere north of 100 vertical market software (VMS) businesses across a wide range of industries and geographies. In late-2020, Volaris created a new brand specifically for their communications and media businesses called Lumine. At the time, there were 15 VMS businesses (16 acquisitions with one tucked into an existing business) amalgamated into the Lumine portfolio which were acquired between 2014 and 2020. Ignoring the latest WideOrbit acquisition, Lumine now has 23 distinct VMS businesses with 6 additional acquisitions completed in 2021 and 2 in 2022. Exhibit A shows when these business units (BUs) were acquired and growth in total BUs over time.

The legacy Lumine portfolio is led by David Nyland, who “joined the Volaris Operating Group in 2014 to found and build a Communications and Media business”. He was previously the CEO of two different software businesses in Canada and has apparently overseen every single BU acquisition that now sits within the legacy Lumine portfolio. David has been the CEO of Lumine since the distinct brand was created in 2020, and will sit on the board and continue to be the CEO of Lumine once it’s spun out. Underneath David Nyland are a handful of Group Leaders that are each responsible for overseeing a collection of BUs. Many of these Group Leaders are (or have been) CEOs of Lumine portfolio companies. For example, David Sharpley is a Group Leader responsible for overseeing 9 BUs (I think). He joined CSU as the CEO of Incognito (Lumine’s first acquisition) in 2017, which is a role he continues to hold today. He briefly stepped in as CEO of Velocix (another portfolio company) and is now also the CEO of TOMIA (acquired in mid-2022). Jonas Svenson is a Group Leader in Sweden and was previously the CEO of two different portfolio companies (he joined CSU through the Netadmin acquisition in 2015). While the tenor of these executives isn’t nearly as long as some of the more senior CSU managers, most have been part of the Volaris/Lumine ecosystem for 5+ years. It looks like Lumine has ~10 head office employees with Corporate Development/M&A titles, and while most seem to have joined in the last 2-3 years, it’s encouraging to see that Lumine has built out a dedicated M&A function separate from Volaris/CSU.

I think it’s fair to say that Lumine is David’s baby. Everything that sits in this business was acquired under his watch, and he was certainly responsible for building the team that exists today. So, what has he built?

Portfolio Companies

I looked at each of the 23 VMS businesses within the legacy portfolio to see if there was some common thread between them. In some cases, there were multiple portfolio companies that seemed to compliment each other and might benefit from cross-selling opportunities that they’d only enjoy by being part of the broader Lumine ecosystem. In other cases, I found eclectic businesses in a world of their own, some of which I would be hard pressed to even categorize in the Communications and Media verticals. For example, Symbrio is a Swedish VMS business founded in 2000 and acquired by Lumine in 2020. They provide software for order optimization, purchasing, contract management, invoice management, and RFPs to customers across Scandinavia. These customers often need to order physical parts/materials to complete jobs, and Symbrio has integrated the suppliers of these goods into a platform that looks an awful lot like a marketplace, where Symbrio customers can shop/order directly from suppliers through their software. Of the customers featured on their website, we have a contractor that digitizes buildings with smart technology for heating/cooling/lighting, a few plumbing and gas installation companies, an alliance of electrical contractors, a business that does property development, and a host of other commercial and industrial service providers. For the life of me I can’t see how Symbrio fits in the Communications or Media verticals, but they do look like the prototypical CSU VMS business: clearly a small percentage of the customer wallet, mission-critical, largely serving small to medium sized customers, multi-decade long customer relationships, and a dominant presence in a small niche. Dope.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have something like MDS Global which was launched in the 1990’s and acquired by Lumine in 2019. MDS was the B2B business support system (BSS) software developed in house at a UK-domiciled mobile virtual network operator (MVNO) called MDT in the late 80’s. When MDT was acquired by the UK’s largest network operator in the late 1990’s, MDS was spun out as a separate entity. BSS software helps telcos manage orders, billing, payments, customer management, etc., and MDS was effectively a first mover (or one of the first movers) to sell this software to MVNOs in Europe. Since then, MDS has transitioned that BSS software to a SaaS model, expanded into consumer-facing BSS (from just B2B), and introduced a wide range of complimentary products to their telco customers like managed services, fraud detection software, wholesale billing software, and business analytics tools… to name a few. As I understand it, MDS’ dominant market is the UK (they serve some of the largest network operators like Telefonica and Vodafone), but they also sell BSS and related software to telecommunication businesses in dozens of other countries. Unlike Symbrio, most of these customers appear to be large enterprises/government agencies (not SMBs). In my view, the competitive pressure in enterprise software is higher than in the SMB space, but MDS still seems to be strongly positioned in their core markets. One of the most telling signs of MDS revenue durability is the fact that Telefonica UK – one of the largest mobile network operators in the UK – has been using some version of MDS software since the 1990’s!

In 2020 – one year after the MDS acquisition – Lumine acquired another UK-based business called Lifecycle that also sells software into the telco space. Lifecycle was also founded in the 1990’s and sells BSS software alongside a range of other products like online charging systems (OCS), fraud protection, and software for contact centers. Where MDS worked with large network operators like Telefonica and Vodafone, Lifecycle had worked on multiple projects for Three (the fourth largest mobile network operator in the UK). Three hired Lifecycle to help them launch a discounted mobile brand in 2017 called SMARTY, and from what I can tell Lifecycle helped develop a bespoke software solution over the course of 7 months to power SMARTY (which is still being used today). After that project, Lifecycle worked with Three to launch another MVNO and install OCS software for future MVNOs. This appears to be a much smaller business than MDS, but they do have a strong relationship with one of the largest mobile network operators in the UK (alongside a few other MVNO customers). It seems totally possible that after Lumine acquired MDS, someone from MDS flagged Lifecycle as a good complimentary acquisition target. Kim Craven, the founder of Lifecycle (who has since retired), cited “access to a vast telco customer network” as one reason for choosing to sell to Lumine, and in one case study Lumine noted that “Lifecycle is spending time with other Lumine portfolio businesses to learn more about operational best practices, meet industry peers, and assess natural synergies and complementary product offerings”. Historically, I don’t think CSU business units worked together that closely (outside of sharing best practices) to drive revenue synergies, but examples like this lead me to believe that Lumine (with an explicit focus on just 1-2 verticals) is more likely to acquire VMS businesses with revenue synergies in mind.

To that last point, Lumine went out and acquired NetEngage and Neural Technologies in 2021 (both UK-based businesses). NetEngage was a carveout from Concentrix with roots going back to 1990 and sells OCS software alongside some other customer-facing products, managed services, and maintenance/support services. They also serve the telco space including Telefonica in the UK and customers in Africa and the Middle East. Neural Technologies was founded in 1990 and sells revenue protection software (fraud management, revenue assurance, credit-risk management, anti-money laundering) and ML/AI analytic tools to telcos, utilities, and finance service companies. According to their website, Neural Technologies serves customers in 45 countries and counts T-Mobile and Telkomsel as customers. In my view, NetEngage and Neural Technologies seem to offer complimentary services to MDS/Lifecycle, and I can see a path to eventual revenue synergies here via cross-selling within Lumine’s growing telco-focused VMS ecosystem.

Some other examples of VMS businesses within the portfolio that paint a broader picture of where Lumine has historically focused include:

Incognito (founded in 1992 and acquired in 2014) was the first acquisition made under Nyland. As I understand it, they provide device management software to telcos (specifically for in-home devices) that helps with automated activation, provisioning, firmware management, and IP address management. They are based out of Canada but have “more than 200 customers” across North America, Europe, Asia, and LATAM. In 2016, Incognito acquired and integrated the operations support systems (OSS) business from Active Broadband Networks.

Tarantula (founded in 2000 and acquired in 2017) sells telecom tower site management software to businesses like American Tower, Motorola Solutions, Indus Tower, Telia, and Arqiva. They are headquartered in Singapore, but their software is used to manage 450k towers in more than 30 countries.

Aleyant (founded in 2005 and acquired in 2018) is based out of Illinois and sells printing software that “simplifies pricing, job management, tracking, and estimating”, and a web-to-print SaaS product that lets customers “receive orders online” and “automate print workflow”. They seem to primarily serve SMB customers in the United States.

Avance Metering (founded in 1996 and acquired in 2019) sells metering software for utilities and telcos that collects, stores, and automates processes associated with data from smart meters (electricity, water, gas, district heating/cooling). Their software is used by “more than 80 customers mainly in the Nordics”.

Velocix (founded in 2002 and acquired in 2019) sells content delivery network (CDN) software and related services for media delivery optimization to businesses like Telus, Liberty Global, Proximus, and Entel (some of the largest operators in their respective markets).

VAS-X (founded in 1999 and acquired in 2021) sells BSS/OSS software to some of the largest telcos in South Africa including Vodacom, who they’ve counted as a customer for more than 20 years.

Wiztivi (founded in 2007 and acquired in 2022) provides cross-platform user-interface (UI) products to what appears to be predominately PayTV and other media customers (sometimes off the shelf, sometimes purpose-built). They also sell a cloud-gaming platform called Streamava that can be integrated into a providers existing environment. Their software is used by Vodafone TV, Liberty Global (Horizon 4), and Altice (Gen8).

One of my first observations after flipping through all 23 BUs was that the average BU had operated for 21 years prior to being acquired by Lumine (the average BU is now 26 years old). These are established businesses with longstanding customer relationships. Most of the software/services sold by this portfolio of businesses are mission critical (the customer can’t run their business without it) and clearly a small share of the total customer wallet, which makes for stickier customers – why switch an inexpensive but mission-critical software and risk something going wrong? In many cases, the BU also sells tailored solutions to their customers (not just off-the-shelf software), which contributes to higher switching costs. Finally, it’s worth noting that the end markets being served by the Lumine portfolio are largely mission-critical themselves (no one who has internet or mobile phones suddenly does without), and I suspect that the ebb and flow of the economic cycle will have very little impact on demand for the products and services that Lumine’s BUs sell. Much of what I loved about CSU in aggregate also seems to exist within this subset of businesses, and this portfolio should provide a consistent and predictable stream of cash flow for Lumine to continue pursuing M&A (I’ll get to that later).

Despite the many similarities between the parent and the spun-out portfolio, there is one striking difference. While CSU, on average, seems to primarily target SMB customers, Lumine disproportionately serves enterprise customers. As a result, the CSU BUs selling to SMBs often have thousands of customers, while Lumine’s BUs seem to frequently have anywhere from 50-200, with the top 10 customers most likely generating the bulk of total revenue. In one In Practise interview, it was noted that “you would be hard-pressed to find 20 companies in the global CSI portfolio who sell to large enterprises”. Well, more than half of those companies now reside in Lumine, and that’s a unique dynamic that makes this a different beast than the parent.

One thing I found very attractive about VMS software in the SMB space was that the addressable markets weren’t large enough to invite serious competition, and whatever competition did exist typically had to contend with CSU’s established and dominant incumbents. I’m not sure how to think about VMS competition in the enterprise space. On the one hand, there are clearly many more competitors and many of these competitors are much larger than Lumine’s individual BUs. For example, Lumine cites companies like Amdocs as competitors in the OSS/BSS space. Amdocs generates 13x more revenue than the entire legacy Lumine portfolio combined, with 10x as much FCF. They also have much higher organic growth, possibly because they can invest more absolute dollars to improve/expand their software and back that up with a bigger sales budget. It’s not inconceivable to me that someone like Amdocs could come along and poach existing Lumine customers – and losing just a handful of large customers would almost certainly have a noticeable impact on total revenue.

On the flipside, most of the enterprise customers purchasing software/services from Lumine are bureaucratic slow-moving behemoths that aren’t well known for “moving fast and breaking things” – are they likely to switch a mission-critical software vendor that hardly moves the needle in their budget? I’m not sure. Maybe that makes this revenue stickier, particularly considering the frequently bespoke (customized) nature of the solutions and the relative durability of businesses like Telus, T-Mobile, and Vodafone vs a single golf-course operator, a homebuilder, or a network of gyms.

The pros and cons of selling software into these specific enterprise markets feel balanced to me, and I honestly can’t decide if it’s a net-negative or a net-positive. All I can say for sure is that Lumine’s customer profile is very different from legacy CSU (or even TOI) – and because I don’t know if that’s good or bad, my bias is to require a higher implied return to own Lumine shares. If you have a strong differentiated view on this front, I encourage you to reach out or comment at the end of this piece.

Legacy Lumine Financials

Exhibit B shows that licenses, maintenance, and recurring revenue represent ~75% of total legacy Lumine sales. These revenue streams are tied to existing business and should be really resilient through the economic cycle. Professional services – the bulk of remaining revenue – is tied to “installation, implementation, training and customization of software”. These services are likely a function of new business or new projects with existing customers. If there was a big recession tomorrow, I’d expect that professional services revenue would contract. Even still, back in 2007/08 CSU had a similar revenue split as Lumine today, and total organic growth was just -3% in in 2009 and -2% in 2010. Whatever happens to the economy in the next year, I feel reasonably confident that the legacy Lumine portfolio would hold up very well.

Prior to the WideOrbit acquisition, Lumine’s 23 VMS businesses plus one other acquisition completed in late 2022 would have generated something likeUS$300-315mn in run-rate revenue. EBITDA margins over the last three years have consistently come in between 30.0% and 31.5% (same ballpark as CSU in the aggregate), so run-rate EBITDA from this portfolio is somewhere in the US$90-95mn range. Like CSU, there is very little capex in this business, so FCF conversion (FCF/EBITDA) has averaged roughly 80%. It follows that run-rate FCF for this business is therefore in the US$75mn range.

Constant-currency organic top-line growth has averaged ~3% over the last 11 quarters that we have data for. The comparable figure for CSU in the aggregate was 1.5%. Barring any revenue synergies, I’d expect organic growth from Lumine to more-or-less track inflation. But as I alluded to earlier, I think there is a real chance that Lumine looks to drive revenue synergies given their specific focus on just a handful of verticals, and I think it’s possible that Lumine’s organic growth will therefore be A) better than CSU as a whole, and B) a few percentage points ahead of inflation.

WideOrbit

Eric Mathewson started WideOrbit in 1999 with the initial goal of making it easier to buy and sell advertising for local broadcast television and local radio. To start, WideOrbit built the software backbone that runs the advertising systems from “order entry to receipt of cash”. You can think about this like the operating system for local media companies. This operating system automates everything like order entry and inventory management, programing (when and for how long ads are shown), A/R management, payments, reporting, and a dozen other very specific things I didn’t even realize needed to be addressed by local media businesses (like automatically making sure advertisements comply with broadcaster-defined rules at the point of order entry). It looks like this software is sold in modules, and by my count there are more than 20 modules on the “platform” today.

After 20+ years, WideOrbit has expanded beyond just local television and radio customers, and now serves national cable networks as well. In addition to linear offerings, they introduced products to serve digital advertisements like Connected TV and OTT solutions. In an interview that took place in 2018, Mathewson indicated that WideOrbit was used by 90% of local television stations in the United States, roughly 50% of local radio stations, and 30% of national cable networks (they’re used by NBC, Fox, Paramount, AMC Networks, Univision, and so on). Judging by the limited financial information provided in the prospectus and the rollout of new modules, I think it’s safe to say that penetration has only gone up since then, particularly considering that they boast a self-reported customer retention rate of 99.9% and organic revenue growth has averaged ~8% over the last two years.

At some point along this journey (tough to say when exactly), WideOrbit software had been installed among a sufficiently large customer base that they could introduce a sell-side marketplace called WO Marketplace that specifically targets local broadcasters. The sell-side marketplace aggregated broadcaster inventory in one place which made it easier for ad agencies and other buyers to discover and place ads. WideOrbit later created a buy-side platform called ZingX that integrated with WO Marketplace. With ZingX, ad agencies and other buyers can set advertising budgets, automatically optimize those budgets as sell-side inventory refreshes, get the tools to target more specific audiences/target markets, receive detailed impression data, and streamline payments (if they advertise across 100 stations, they’ll get one consolidated bill).

It looks like the initial iteration of WO Marketplace was created in 2015 (under a different name), but WideOrbit launched a new version of WO Marketplace in 2022, and the ZingX trademark was only filed in 2021. Unfortunately, I can’t find more historical information than that, but it looks to me that the marketplace in its current form is relatively nascent. Exhibit C shows WideOrbit revenue contribution by category and shows that software licenses generate 88-89% of total revenue while Advertising & Content Delivery (the marketplace attribution) is just 3% so far in 2022. This supports the notion that the marketplace business has a long way to go from a penetration perspective. At the same time, Advertising & Content Delivery revenue is the fastest growing subsegment within WideOrbit, having grown by 98% y/y in 2021 and 78% y/y through the first three quarters of 2022.

According to WideOrbit, their software manages US$37bn of ad revenue every year, and by my estimate slightly more than half of that comes from local TV broadcasters (not national cable networks). WideOrbit’s total revenue as a percentage of this ad revenue is a paltry 48 bps, and the Advertising & Content Delivery revenue is a paltry 1 bp (implying extremely low penetration). If WideOrbit’s marketplace captured a 25% share of the ad revenue they touch (or 50% of local TV broadcasters), and the marketplace clipped a 1.0% take-rate, then this business could generate an incremental ~US$90-100mn in revenue. That would be a 50% increase on total 2022 annualized revenue. Similarly, they’d generate an incremental US$100mn in revenue if they captured just 10% of this ad revenue on their marketplace and charged a 3.0% take-rate. That revenue would come with extremely high incremental margins, and I suspect most would flow down to FCF. I have no strong view on the likelihood of marketplace success, but the platform seems attractive, is gaining some early traction, and WideOrbit already has deep relationships with the vast majority of local TV broadcasters in the country. If nothing else, this is a compelling option embedded in what otherwise seems to be a consistent and durable cash-generating base business.

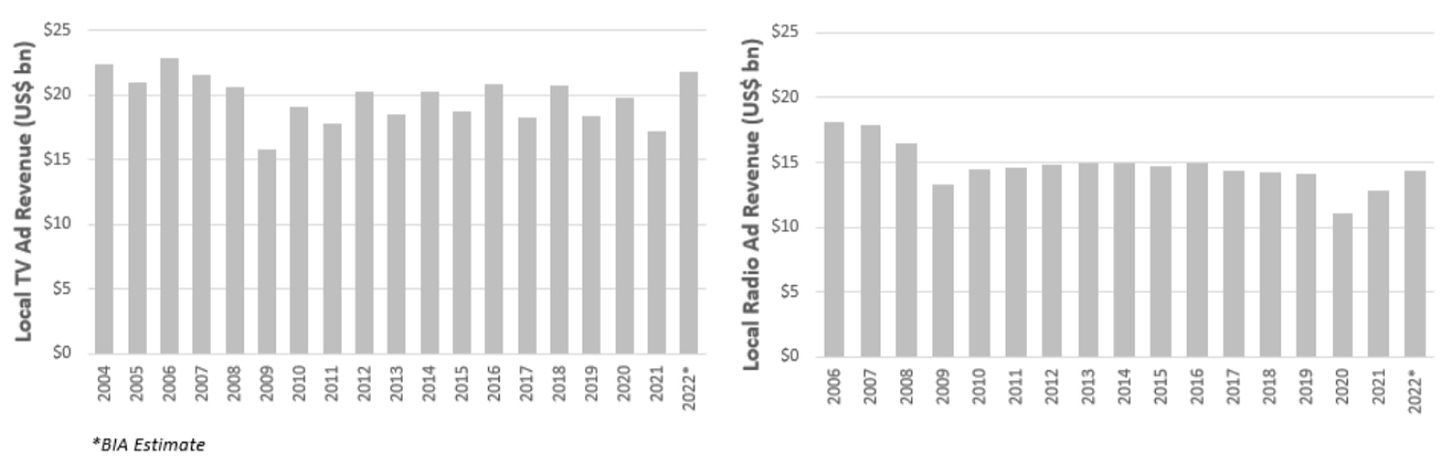

To that last point, I initially expected to find that local TV ad revenue was in a steep perpetual decline but was pleasantly surprised to learn that wasn’t actually the case. Exhibit D shows local TV ad revenue as reported by the BIA, and it’s been remarkably stable over the last decade in absolute dollar terms, despite losing share of total ad spending (total ad spending is up more than 30% over the last twenty years vs local TV ad revenue that’s down slightly). The data paints a similar picture for local radio ad revenue. These businesses certainly aren’t thriving, but neither do they seem threatened with extinction any time soon. Against that backdrop, I think there is a customer base here that should support a long runway of FCF generation from WideOrbit well into the future. I’d also note that if total ad revenue does start to decline more materially, the value proposition of WideOrbit’s marketplace probably goes up for sellers who might become increasingly hungry to source demand.

WideOrbit Acquisition Economics

Lumine agreed to acquire WideOrbit for a gross purchase price of US$497mn (although technically they are only acquiring 55% of the business, and WideOrbit shareholders are rolling 45% into equity of the spin-out). This business is likely to generate something like US$40-45mn of operating income in 2022, which implies 11.0-12.5x EV/EBIT. From a FCF yield perspective, I estimate that it’s in the 6.0-7.0% range. That’s quite expensive relative to the typical CSU or Lumine transaction (which I’ll get to later), even if we acknowledge the higher organic growth which was 10% in 2021 and 6% in 2022YTD vs. the legacy Lumine portfolio of 5.6% and 0.0% respectively (adjusted based on a note in the prospectus).

There might be some ulterior motives for completing this acquisition, but I have to think that senior CSU executives (who, let’s get real, had to greenlight this) saw a compelling path to achieving their IRR hurdle rates. While we don’t know what those hurdle rates are exactly, my best guess is that they’re somewhere in the mid-teens range. The only obvious ways I can get there is if the marketplace works and/or if CSU thought WideOrbit had unexercised pricing power. To that last point, don’t forget that WideOrbit’s implied cut of total ad revenue moving through their platform is just 48 bps. If they took that 10bps higher, FCF would more-or-less double. Is that a stretch? Maybe. But WideOrbit clearly has the box in this space, with the vast majority of local TV broadcasters and radio stations depending on this mission-critical software. I’d be surprised if customer churn increased by enough to offset a 10bps increase in the implied take-rate over 5 years, particularly considering the self-reported retention rate of 99.9%.

All told, this looks like an expensive deal at first blush, but it wouldn’t surprise me if WideOrbit delivered organic growth of 10%+/year over the next decade if either of the two levers mentioned above are pulled successfully. I’m shooting from the hip here, but it’s hard to bet against what is an invariably successful CSU M&A engine.

Spin Out Transaction

Following the acquisition of WideOrbit, CSU will spin out shares in the combined entity (Lumine) as a dividend in-kind. CSU shareholders will receive 63.6mn Subordinate Voting Shares in Lumine (these are the common shares that will trade freely immediately). The Rollover Shareholders (owners of WideOrbit) will receive 10.2mn Special Shares, which are convertible to cash or Subordinate Voting Shares under a variety of circumstances that I’ll outline shortly, and effectively covers part of the WideOrbit purchase price. Finally, CSU will be issued 63.6mn Preferred Shares which are also convertible to cash or Subordinate Voting Shares. CSU will also receive 1 Super Voting Share that entitle them to 50.1% of the vote so long as they retain at least 15% of the Subordinate Voting Shares on a fully diluted basis.

Outside of some fringe scenarios, the Special Shares convert to Subordinate Voting Shares at a ratio of 3.4:1 and the Preferred Shares convert at a ratio of 2.4:1. This means that the most likely fully diluted Subordinate Voting Share count is 253.1mn. I emphasize this because I’m confident that many market participants got this wrong on TOI by using too few fully diluted shares to value that business. On a fully diluted basis this means that: CSU controls 80.6% of the votes and retains 61.1% of the economic interest; the Rollover Shareholders control 6.9% of the votes and retain 13.8% of the economic interest; and public shareholders control 12.5% of the votes and retain a 25.1% economic interest.

Conversion is a little tricky since both Lumine Group and the holders of Preferred Shares and Special Shares have different options to convert. There is a Mandatory Conversion Date that occurs on the later of A) 12 months after the first day shares start trading, or B) 10 days after the closing trading price of Subordinate Voting Shares is => C$9.84. On conversion, CSU and the Rollover Shareholders basically have the option to take the converted shares or to take an equivalent value in cash. If the share price was high at the moment of conversion, CSU and the Rollover Shareholders could effectively sell their stake in Lumine Group for cash – Lumine Group wouldn’t have the cash on hand to cover that payment, so would have to find replacement investors. On the flipside, both CSU and the Rollover Shareholders also received Share Retraction Rights, which gives them the option to sell some or all of their Preferred/Special Shares at any point prior to the Mandatory Conversion Date. Lumine Group would be required to either A) repurchase those securities for cash, or B) issue Subordinate Voting Shares of equal value to the Initial Face Value of the securities. You can find the calculation in my model provided above, but if the Lumine Group share price falls below US$8.95/share (~17x pro forma EV/EBITDA vs CSU and TOI at ~18x and ~17x currently), then CSU and the Rollover Shareholders can convert their Preferred/Special Shares at a higher conversion ratio. In essence, CSU and the Rollover Shareholders acquire a larger stake in Lumine Group then they would have had otherwise, and regular holders of the Subordinate Voting Shares get diluted.

This is important because it provides CSU and the Rollover Shareholders with meaningful downside protection if Lumine’s share price falls well below intrinsic value. Implicitly, CSU has an option to buy more shares at a “low” valuation and sell shares at a “high” valuation. If the market priced Lumine Group inappropriately (too cheap or too expensive), CSU has an opportunity to extract value. Those are great options for CSU shareholders, but I don’t love that public shareholders can get seriously diluted below US$8.95/share. Even still, CSU is a meticulous decision-making machine, and they clearly set this $US8.95/share threshold at a place where they would see it as an attractive opportunity. After the Mandatory Conversion Date has passed or all units have converted, you can almost think about this as the no-brainer price where savvy insiders would love to take a greater piece of the pie (implying you would too).

In Exhibit E I show the pro forma Lumine org chart and the fully diluted ownership structure assuming total fully-diluted shares remains at 253mn. I also show what happens to the fully diluted share count and the ownership interest of public shareholders at various Lumine share prices at conversion of the Preferred/Special shares. WideOrbit is the primary business in the Media #1 OG, while I suspect that one of the Communication OG’s will consist of all the telco VMS businesses, and the other Communication OG will be a collection of everything else that doesn’t easily fit into the other two categories.

Pro forma financials

Run-rate revenue of the pro forma entity is likely somewhere around US$485-490mn. WideOrbit EBITDA margins are a few points lower than the legacy Lumine portfolio, so pro forma margins are likely 28-29% out of the gate, which gets us to run-rate EBITDA of US$135-140mn. Once we knock off lease payments, minimal capex, post-acquisition settlement payments, and taxes, we’re left with something like US$110mn of free cash flow to firm.

From there we need to adjust for some new debt and dividends on the Preferred/Special shares. In conjunction with the WideOrbit acquisition Lumine is looking to secure some debt financing from third parties, but in the absence of that third-party debt CSU will extend a US$94mn 5-year loan to Lumine at a 4% fixed interest rate. Lumine also took out a US$39mn 4-year floating-rate term loan in October of 2022 to help fund either the Wiztivi or Morse Holding (TOMIA) acquisition. It’s not clear what the floating rate spread is on that US$39mn loan, but my best guess is that the aggregate interest expense from both loans will end up being US$7-8mn/year (w.a. interest rate of 5%).

Until the Preferred/Special shares convert, both unitholders will be paid a 5% dividend yield on the Initial Face Value of the respective securities. That’s another ~US$80mn out the door assuming neither of those units convert until 2024.

If we assume that the full interest/dividend expense is tax-deductible, that reduces free cash flow to equity to just US$40-45mn. If we toss in an extra US$30mn of cash on the balance sheet, we get something like US$70mn of available capacity that can be tapped for M&A in 2023 in the absence of any additional debt financing (which I don’t expect they’ll use considering pro forma D/EBITDA will already be ~1.0x). Gross M&A was US$30mn, US$44mn, and US$119mn in 2020, 2021, and 2022YTD respectively (ignoring WideOrbit). With that in mind, I think there is plenty of capacity here for the M&A engine to power ahead despite the incremental interest/dividend expense that’s likely to drag down FCFE in 2023. And once the Preferred/Special shares convert, the challenge will shift from short-term funding to actually finding enough opportunities to deploy US$100+mn in FCFE (and growing).

The pro forma entity will generate something like 45% of total revenue from North America, 45% from EMEA, and 10% from the RoW.

I find everything easier to absorb with visuals, so if you’re like me, please see Exhibit F for a more detailed look at pro forma financials and how I arrived at the FCFF and FCFE estimates. There are a few estimates required here, but I think the margin of error is small.

Management and Governance

Of the seven directors on the board, CSU will get to appoint six so long as they hold a 25% fully diluted interest, while the Majority Rollover Shareholder will get to appoint one so long as they hold a 4% fully diluted interest. There will be two independent directors (we don’t know who those are yet), but the remaining five will consist of Mark Miller (CEO of Volaris and COO of CSU), Brian Beattie (CFO of Volaris), David Nyland (CEO of Lumine Group), Robin Van Poelje (Chairman/CEO of TOI), and Eric Mathewson (CEO of WideOrbit). There are some heavy hitters in this group, particularly Mark and Robin.

Neither Mark or Brian will be paid by Lumine Group (instead, they will be paid by Volaris), but all other directors and executives will be paid some split of base salary and cash bonus. Like CSU, a portion of the after-tax annual cash bonus will be used to purchase Subordinate Voting Shares in the open market, and those shares will be held in escrow for 3-5 years. I’m not exactly sure what percentage of the after-tax bonus must be used to purchase stock for executives, but it’s 50% for directors and I imagine it’s something similar for executives (if not higher). The actual cash bonus amount scales up and down based on the difference between ROIC and the risk-free rate (if ROIC is less than the risk-free rate, no bonus is paid). Overall, I like the alignment and incentive plan, which looks an awful lot like how the parent is structured. There was no explicit mention of this in the preliminary prospectus, but I’d imagine that most senior members within the 20+ BUs will also be required to invest some portion of their after-tax bonus into Lumine Group equity – this is the model at CSU/TOI, and I see no reason why they’d change that here.

While Lumine Group will operate with autonomy from the parent, CSU has put some handcuffs on them. For example, any acquisition above US$100mn requires approval by the board of directors of CSU. I also snipped the below paragraph from the prospectus, which shows that CSU will retain some control about where they allocate acquisitions (emphasis my own).

“The parties to the Shareholders Agreement have agreed that the Constellation Group will continue to consider possible acquisition opportunities in the ordinary course of its business and may, from time to time, recommend or allocate such acquisition opportunities to the Company. CSI will have discretion to determine the suitability of such opportunities for the Company and to allocate such opportunities among the Company or other operating groups within CSI as it deems appropriate. The question of whether a particular acquisition opportunity is suitable or appropriate for the Company is highly subjective and will be made at CSI’s discretion based on various factors. If CSI determines that an acquisition opportunity is not suitable or appropriate for the Company, CSI or one of CSI’s operating groups may still pursue such opportunity”

It’s worth flagging that CSU may at any time decide to allocate acquisitions of adjacent businesses that they source to a CSU operating group and not Lumine. Roughly 50% of the M&A completed at Lumine in FY2020 and FY2021 was a transfer from CSU and not a direct acquisition from within Lumine. Against that backdrop, I think Lumine is going to depend quite heavily on CSU to help source deals if they want to keep the M&A engine running at full steam – at least in the near-to-medium term. That’s especially true considering the relative size of CSUs network, their reputation within the industry, and the fact that most Lumine BUs are new to the fold and need time to mature before pursuing M&A on their own. I’d be remiss not to highlight this as a risk, but it’s important to also recognize that the same language was included in the TOI prospectus, and TOI has had no problem sourcing and completing new acquisitions. In one instance, TOI and another CSU OG (Vela) even shared an acquisition (I’m not sure if it was 50/50, but they both own a stake in this new BU). CSU also has a vested interest in seeing Lumine succeed, particularly if they want to continue spinning out new entities – which they do.

Rationale for the spin-out

In my view, the most relevant motivation (from the perspective of soon-to-be Lumine shareholders) for spinning out new businesses from the CSU portfolio is to combat bureaucracy creep. As I discussed in my original CSU deep-dive (which you can find here), one of the businesses strongest competitive advantages is their decentralized organizational structure and “human-scale” business units. I’ve long thought that one of the biggest risks to the CSU thesis is that they lose this magic (not that some other competitor effectively copies their playbook). In Mark Leonard’s own words (emphasis my own):

“When a VMS business is small, its manager usually has five or six functional managers to work with: Marketing & Sales, Research & Development ("R&D"), Professional Services, Maintenance & Support and General & Administration. Each of those functional managers starts off heading a single working group. If the business leader is smart, energetic and has integrity, these tend to be halcyon days. All the employees know each other, and if a team member isn't trusted and pulling his weight, he tends to get weeded-out. If employees are talented, they can be quirky, as long as they are working for the greater good of the business. Priorities are clear, systems haven't had time to metastasise, rules are few, trust and communication are high, and the focus tends to be on how to increase the size of the pie, not how it gets divided. That's how I remember my favourite venture investments when I was a venture capitalist, and it's how I remember many of the early CSI acquisitions”

As the business unit grows…

“A new level of middle managers will be born, with all the potential for overhead creation, politics, and bureaucracy that comes with another tier of middle managers. The larger a business gets, the more difficult it becomes to manage, and the more policies, procedures, systems, rules and regulations are generated to handle the growing complexity. Talented people get frustrated, innovation suffers, and the focus shifts from customers and markets to internal communication, cost control, and rule enforcement. The quirky but talented rarely survive in this environment. A huge body of academic research confirms that complexity and co-ordination effort increase at a much faster rate than headcount in a growing organisation. If the BU is small enough, and has a competent BU manager who has several years experience in the vertical, and good functional managers, then he/she will be able to cope with complexity for a while, making the right calls to optimise organic growth as the business grows. The challenge of running a BU of this size is human-scaled”

Mark studied other high-performance conglomerates (HPCs), and goes on to say:

“One of the HPC’s that we studied was Illinois Tool Works Inc. (“ITW”). It has hundreds of BU’s. We began following the company from afar in 2005. The most relevant period in ITW’s history for CSI was the tenure of John Nichols. Nichols began consulting to ITW in 1979, and appears to have been the primary author of its decentralisation strategy. He was CEO as the company went from $369 million in revenues in 1981 to $4.2 billion in 1995 ($6.7 billion in today’s dollars). Prior to Nichols's tenure, ITW had acquired only 3 businesses. During his tenure, ITW aggressively acquired and often split the larger acquisitions into smaller BU’s. ITW had 365 separate operating units by 1996 when Nichols retired. I’m sorry I didn’t reach out to some of the ITW employees and ex-employees until 2015. When I did talk with one of the senior managers, he said (I’m paraphrasing) “Something wonderful happens when you spin off a new business unit.” … “With a clean sheet of paper, the leader only takes those he needs. They set up in an open office with good communication and no overheads. They cover for each other. They leave all the bureaucracy and the crap behind”. I did record a couple of verbatim quotes from that conversation: "Don't share sales, R&D, HR, etc. because the accountants never get the allocations right and the business units always treat the allocated costs as outside their control", and "When you get big you lose entrepreneurship"”

All of Mark’s comments were specifically about individual business units, but I think the same logic applies to operating groups. At some point, every operating group is going to reach a scale where a new level of middle-managers is created, and the operating group starts to lose entrepreneurship.

The other interesting challenge that CSU faces as they scale is how to best maintain strong financial alignment. Historically, people in leadership positions all the way from Mark Leonard down to the smallest BUs have been required to invest a portion of their after-tax bonus in CSU stock. But as the number of BUs increases, the link between individual BU performance and CSU’s total performance grows weaker and weaker, to the point that exceptional individual BU performance could have an indiscernible impact on CSU’s total financial results. I can see how that would be frustrating for BU managers/employees who are required to own CSU stock, and don’t have long-term incentives tied to a better proxy for their specific performance.

Spinning out Lumine addresses both of those challenges. It’s a small head office that now has full control over their own destiny. “With a clean sheet of paper, the leader only takes those he needs. They set up in an open office with good communication and no overheads. They cover for each other. They leave all the bureaucracy and the crap behind”. Equally important, any employees who would have had to own CSU shares now gets to invest in Lumine shares. That should create a much cleaner direct-drive link between individual performance (or BU performance) and financial outcomes. Similarly, the tangible financial upside of collaborating with other BUs is now higher (cross-selling, introducing another BU manager to a potential target, etc.). I suspect this small change will go a long way at maintaining the entrepreneurial spirit at Lumine.

There is one final reason for the spin-out that isn’t relevant to go-forward Lumine shareholders, but is very relevant to CSU shareholders. It’s deserving of a more detailed explanation, so I’ve put a pin in it for now, but I’ll expand on this when I publish an update on CSU in the next day or two - stay tuned!

M&A Engine

Like CSU and TOI, the most important driver of Lumine’s valuation is M&A. How many targets are there? How big are those targets? Is competition to acquire these businesses materially different than other VMS sectors? Are valuations for VMS businesses in the Communications and Media verticals comparable to valuations for VMS businesses in other sectors? Can Lumine scale M&A just as effectively as any of CSU’s legacy operating groups?

A good place to start looking for answers is to look at Lumine’s track record to-date. In the prospectus we were provided with three relevant pieces of information:

The average gross purchase price of all acquisitions completed prior to Wiztivi and WideOrbit was US$11.7mn

Lumine completed 23 acquisitions prior to Wiztivi and WideOrbit

Run-rate revenue from those 23 acquisitions is roughly US$280mn (which I estimated by annualizing 2022YTD revenue from all acquired businesses owned by the end of 3Q22)

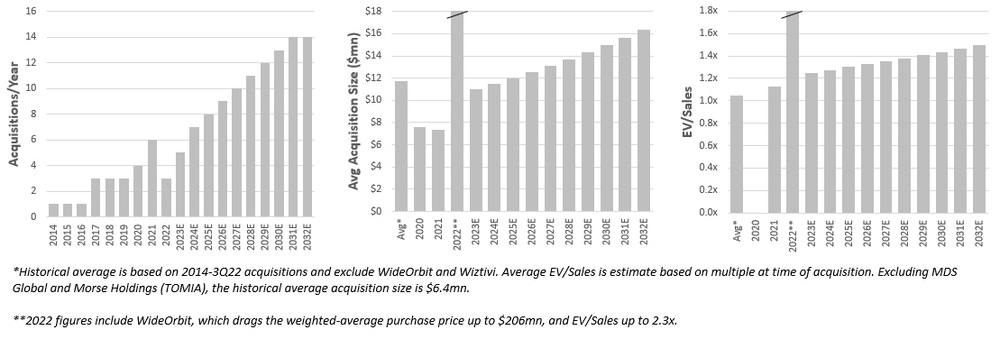

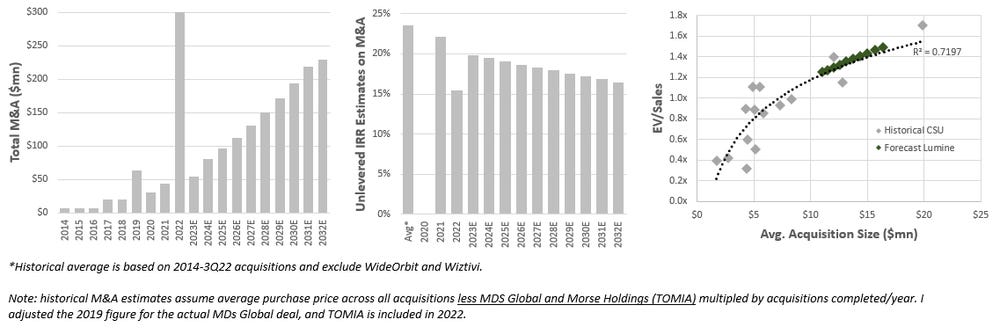

That get’s us a cumulative M&A figure of US$269mn on US$280mn of revenue today, or 0.96x initial EV to 2022 run-rate sales. If organic growth was 2-3% historically (we don’t have information prior to 2020), that would imply something like 1.0-1.1x EV/Sales at the time of acquisition (most acquisitions were completed in the last 2-3 years). At 30% EBITDA margins that works out to 3.3-3.7x EV/EBITDA at the time of acquisition. By my math, that works out to an unlevered IRR of 20-25%. No matter how we look at it, these multiples/implied IRRs are very close to what we’ve seen from CSU in the aggregate. At a minimum, I think we can deduce that completing M&A in these verticals isn’t materially different from the average VMS vertical if they can find targets in that size sweet spot.

We also know that Lumine has ramped up total acquisitions/year, and the FY2021 data shows that they completed 6 acquisitions at an average price of US$7.4mn at an average multiple of 1.1x EV/Sales or 3.7x EV/EBITDA. Again, I think we can deduce that Lumine has the technical capacity (perhaps with some help sourcing deals from CSU) to scale M&A without sacrificing returns so long as they can find acquisition targets in their sweet spot. To the extent that there are sellers looking for a home, I think it’s clear that the decentralized M&A approach (see my CSU deep-dive) and reputation in industry should help Lumine/CSU surface and close on deals.

If M&A characteristics in these verticals are similar to the VMS market as a whole, and Lumine has the capacity to ramp up M&A effectively, then the most important remaining question is just how many targets are there in these verticals? Unfortunately, I haven’t found any hard data to answer that question, but I can make a few observations.

The first observation is that there are probably many thousands of VMS businesses like Symbrio and Aleyant that I covered earlier that don’t exactly fit nicely into the Communication or Media verticals, but nonetheless seem to have a home inside Lumine and serve the more traditional SMB space. I see no reason why Lumine wouldn’t make acquisitions like this is if their team finds a deal. But to the extent that Lumine continues to rely on CSU to source deals, CSU could very well allocate a transaction to another operating group if it isn’t explicitly a Communications or Media business. Since Lumine is a new entity, with BUs that haven’t been owned for very long, and way fewer BUs/employees looking for acquisition targets, I suspect that they will struggle to self-source many acquisitions like Symbrio and Aleyant in the near future. Nevertheless, as Lumine matures and their network grows, I don’t see any compelling reason that they would stay confined to the Communication and Media verticals if one of their BU managers found an exceptional VMS business for sale in another vertical. After all, TOI was spun-out to be a subsidiary focused on Europe and has recently talked about expanding outside of Europe – these aren’t be-all end-all edicts.

The second observation is that some of the specific niches Lumine has a stranglehold in today are already concentrated and seem to be dominated by a handful of multi-billion-dollar businesses. For example, Lumine owns a handful of OSS/BSS software businesses, and while the OSS/BSS market is pegged at ~US$50bn/year globally, the top 20 vendors seem to have >50% market share (like Amdocs, Ericsson, HPE, Huawei, and IBM). Many of these vendors seem to have a large established presence in North America, and maybe that explains why Lumine has only acquired BSS/OSS businesses in the UK and South Africa. Not to mention, the MDS acquisition (initial BSS software foray) was probably 5-6x larger than Lumine’s average VMS deal, and if you put a gun to my head I’d guess that returns on that deal were lower than returns on smaller deals. Some of these markets that serve enterprise customers probably have fewer acquisition targets than other verticals, and many of those targets are bound to be larger tickets than the average CSU acquisition (another example is Morse Holdings, which was completed this year for US$83.9mn at an EV/Sales multiple of 1.8x). My concern here would be that Lumine generates lower incremental returns from M&A than TOI or CSU’s average small VMS deal. On the flipside, this dynamic probably helps Lumine scale M&A in absolute dollars a little easier than a strategy exclusively focused on US$7mn transactions. Even still, I don’t think doubling or tripling the number of acquisitions completed/year will be easy going.

Despite some of these idiosyncratic challenges, I do think Lumine is likely to deploy a significant portion of their FCFE at reasonably attractive incremental returns for a long time to come – in part because they have modest absolute FCF dollars to deploy and don’t need to complete that many deals to run the well dry. Returns might even be comparable/better than CSU if their narrow focus on a handful of verticals can help surface revenue synergies that haven’t historically been part of the CSU playbook (I wouldn’t pay for that, but it’s still worth considering).

Valuation

To arrive at my base case valuation I come up with assumptions for a range of key drivers. I’ve laid out those assumptions and some context for my thinking below.

Organic Growth

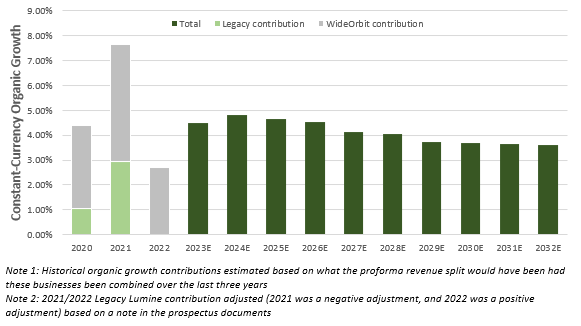

Unfortunately, we don’t have 10 years of historical data to evaluate here. What we do know is that constant currency organic growth from the legacy Lumine portfolio has been roughly 3.0% over the last 11 quarters. We also know that WideOrbit organic growth was a little higher than 8.0% over the last two years, and I think there are a couple compelling reasons to suggest that WideOrbit can continue to organically grow faster than the legacy portfolio for the next 10 years. In the base case, I assume that the legacy portfolio and new acquisitions continue to generate 3.0% organic growth. This should be more-or-less in-line with inflation, so implicitly I’m not giving Lumine any value for revenue synergies that might very well materialize with this new focused subsidiary. I might be convinced to pay for that in the future if we saw some evidence of it playing out, but for now I can’t get there. For WideOrbit (which is initially ~35% of pro forma revenue), I assume a 7% organic growth CAGR over the forecast period. That’s roughly what I think would be required for the acquisition to generate close to a 15% levered IRR (which is what I believe CSU would have been targeting when they made this acquisition). The aggregate organic growth in my base case can be found in Exhibit G alongside what I estimate historical organic growth would have been at the combined WideOrbit and legacy Lumine business.

The margin of error here is probably high, especially considering how much of the future organic growth in the base case is dependent on WideOrbit (WideOrbit is still 18% of total revenue by the terminal year). If you don’t buy into these assumptions, I’d refer you to the sensitivity analysis section to see how sensitive the base case is to these assumptions. Spoiler alert, it’s not that sensitive.

EBITDA Margins

Exhibit H shows EBITDA margins in my base case vs historical margins for the legacy Lumine portfolio, WideOrbit, and what margins would have been had the two businesses been combined from 2020-2022. Margins from the combined businesses historically are reasonably close to CSU’s aggregate margins. I haven’t seen any compelling data to suggest that margins compress or expand meaningfully in the future, so settled on ~28% as a reasonable run-rate.

Qualitatively, I think we can assume that these VMS businesses have sufficiently sticky customers that they can easily flow any input cost inflation through to software prices (CSU executives have talked about this ad nauseam), which theoretically prevents margin compression. I suppose the only argument that could be made for margin expansion is success from the WideOrbit marketplace (which would probably have incremental margins >50%). But once again, without any real evidence of that business getting to sufficient scale, it seems safe to ignore. I suspect the margin of error here is narrow enough either way.

M&A

Exhibit I shows my base case assumptions for the key drivers of M&A alongside some historical data for comparison. The number of acquisitions completed in these verticals has clearly gone up over time, with Lumine closing 6 investments in 2021 up from just 1-3 in the early years of David Nyland’s tenor. I find it encouraging that acquisitions/year have continued to climb after Lumine became a distinct brand within Volaris and built out a broader internal M&A function. This last year is a bit of an outlier, with fewer but much larger acquisitions (including WideOrbit) that likely sucked up resources for much of the year (in addition to all the work that likely went behind planning for the spin-out). I suspect that 2023 will be a slower year given the Preferred/Special dividend drag on FCFE and the resources being tied up on WideOrbit, but that the number of acquisitions completed will climb steadily thereafter. For context, TSS (the operating group within TOI that got spun out two years ago) completed 17 acquisitions in 2020 prior to getting spun out, and just completed 28 acquisitions in 2022. Against that backdrop, I think it’s reasonable to assume that Lumine can continue to ramp total acquisitions/year, particularly as some of their BUs mature and more people take on M&A responsibilities (the magic of their decentralized approach). It’s also important to recognize that Lumine will continue to benefit from CSUs network to help source deals. On the flipside, the team at WideOrbit is likely unaccustomed to M&A, and at least in the near-to-medium term I don’t think they’ll be contributing to this M&A engine (so we’re relying on legacy Lumine to do this).

As I alluded to earlier in this piece, I suspect Lumine will acquire more large businesses in addition to the typical small VMS deals CSU is famous for (US$5-7mn ticket size), largely because they’re fishing in a pond that serves enterprise customers and those tend to be larger companies. The second order effect from acquiring larger businesses is that I suspect Lumine will pay slightly higher multiples on average. And we’ve seen that play out in 2022 with two large deals for US$36 and US$84mn completed for closer to 1.8x EV/Sales.

Exhibit J shows the outputs that get produced with the above assumptions. Notably, the graph on the far right shows EV/Sales vs average acquisition size in the base case vs comparable figures for CSU from 2008-2022. This suggests that A) Lumine will pursue larger acquisitions on average, and B) they’ll pay slightly more than the 1.0-1.1x EV/Sales that CSU has realized historically as a result. Perhaps a tad punitive but seems reasonable enough for a base case and generally consistent with what historical CSU data would suggest if I’m right about deal size. The readthrough is that I have incremental unlevered IRRs on M&A falling from about 20% next year to 16% in the terminal year, which should be more-or-less in-line with CSU’s hurdle rates on a blended basis.

Admittedly, the range of outcomes here is a mile wide – I’m shooting from the hip for base case estimates, and it wouldn’t surprise me at all if Lumine deployed US$200mn in 2026 vs the ~US$115mn in this scenario. I still think this is a useful exercise to go through, but once again refer you to the sensitivity analysis section below.

Financial Position

If we take all these base case estimates at face value, we can back into Lumine’s reinvestment rate over time (the % of sustaining FCF that gets deployed back into VMS M&A). Exhibit K shows what that reinvestment rate looks like in the base case vs 2020-22 reinvestment rates. Note that even as I have M&A ramping up significantly, their reinvestment rate doesn’t get anywhere close to 100%. There is certainly room for Lumine to pursue a lot more M&A than the base case, so the limiting factor is really finding enough deals that meet their hurdle rates in these verticals, and that’s where a bit of my skepticism shows through in these estimates. I think one contributing factor is that WideOrbit will generate a large portion of total FCF, and I just don’t see how that business (the majority of Media #1 Operating Group) is going to contribute to the M&A flywheel any time soon. Note that if we ignore WideOrbit, the cumulative reinvestment rate from 2020-3Q22 was 116% thanks in large part to the other large acquisitions completed in 2022 (Wiztivi was US$36mn and TOMIA was US$84mn). So, if I end up being wrong in the base case, the most likely reason is that they do end up completing a lot more M&A than I expect.

In any event, Exhibit L shows sources/uses of cash over the forecast period in this scenario. Presumably, if Lumine can’t deploy all of their FCF then they’d repay the modest debt balances they’ll have after the WideOrbit acquisition. Even still, they’ll build somewhere close to US$1.0bn in cash over the next 10 years. Either they deploy an additional US$1.0bn on M&A (I’m skeptical), or they’ll end up returning a lot of cash to shareholders and be completely unlevered.

Tying it all together in the base case

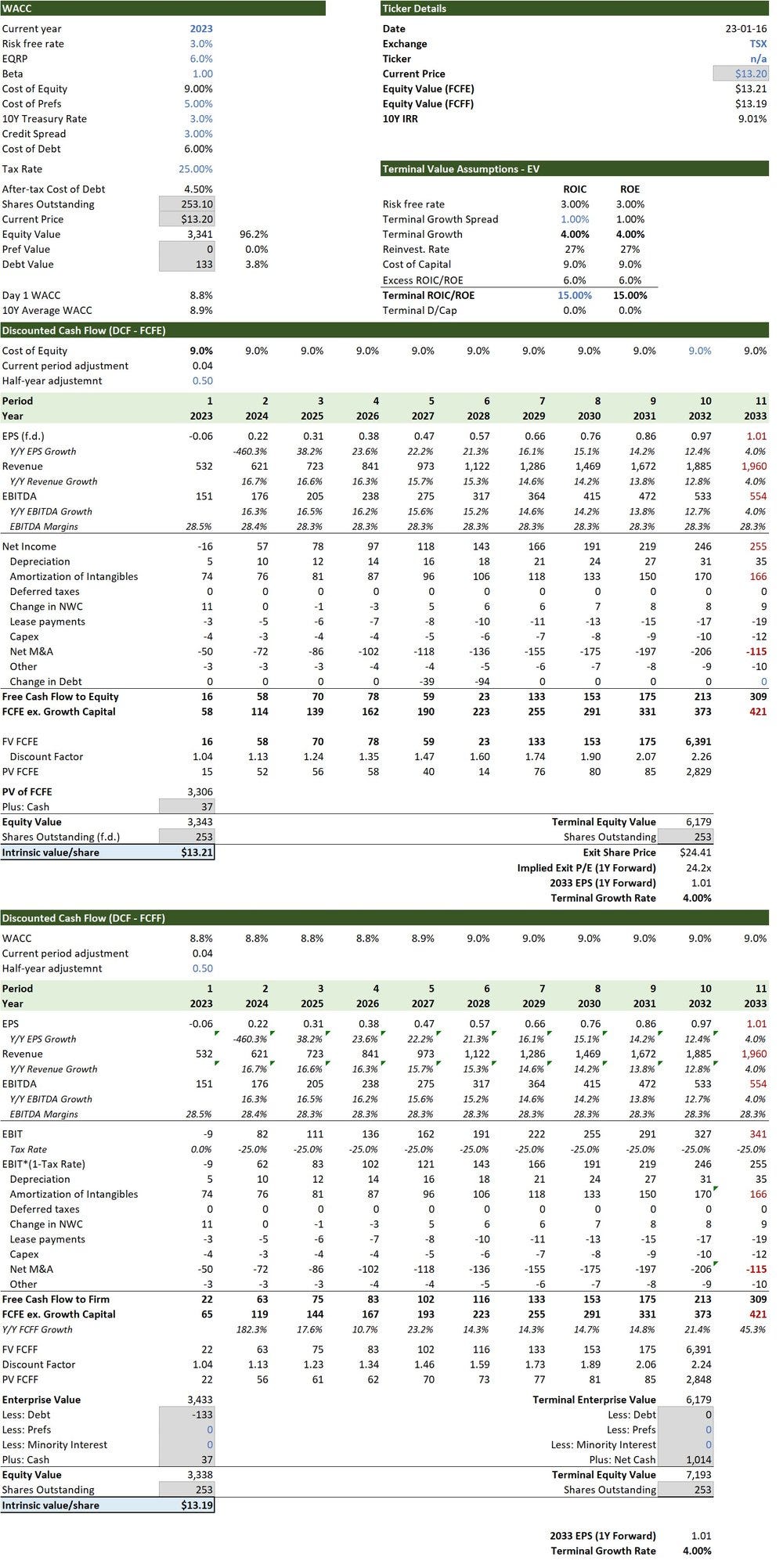

Exhibit M shows a snapshot of my DCF output tab and shows that fair value in the base case is roughly US$13/share using a 9.0% cost of equity, 4.0% terminal growth rate, and 15% terminal ROIC. The implied exit multiple using those assumptions is roughly 24x P/E, 15x P/FCFE, or 11x EV/EBIDTA. Note that terminal P/E looks high because Lumine will still have a large outstanding balance of acquired intangibles, which is largely a non-cash expense but is deductible for cash tax purposes. If we adjust for amortization of intangibles then terminal P/E and P/FCFE are nearly identical.

The base business, using my base case organic growth rates (4.1% CAGR through the forecast period), is valued at roughly US$7.00/share ex. M&A. So nearly half of the value in my base case comes from accretive M&A. The range of outcomes for value generated through M&A is obviously quite wide and that makes for a good segue into sensitivity analysis.

Sensitivity Analysis

The best place to start is a sensitivity on M&A assumptions – both capital deployed and purchase multiples. The sensitivity table in Exhibit N shows my fair value estimates after toggling those two assumptions, along with the readthrough for weighted-average IRRs, reinvestment rates, and total capital deployed. What’s likely to happen if Lumine deploys more capital than the base case is that incremental returns would fall, and vice versa. As such, I’ve taken a stab at illustrating the combination of assumptions that seem reasonable to me (for example, I think it’s very unlikely that they’d deploy US$3.0bn on M&A at 20%+ IRRs, or just US$1.0bn at low-teens IRRs).

Exhibit O shows my base case sensitivity to EBITDA margins and organic growth if we hold all M&A assumptions constant (dollars deployed and IRR on those dollars). Clearly valuation is much less sensitive to changes in these variables than it is to M&A success (or lack thereof). If you were more pessimistic than my base case on both organic growth and margins, but thought the M&A assumptions were reasonable, it wouldn’t move the needle a ton.

Scenario Analysis

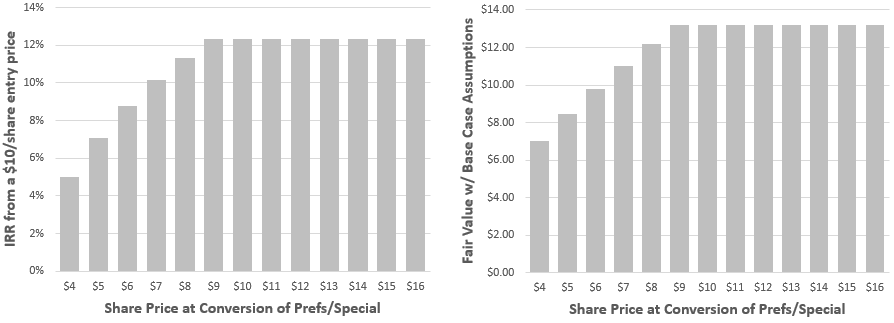

I ran two additional scenarios here with the intention of showing something that resembles my 90% confidence interval. Exhibit P shows these bear and bull case scenarios and the allocation of changes to fair value from my base case. I know you could fly a 747 through that range, but I think it’s indicative of prices where I’d normally confidently take the over and under on – it’s also a reflection that the range of outcomes is very wide. I emphasize “normally” because for some short period after Lumine gets listed public shareholders in Lumine are faced with the added risk of dilution because of the Share Retraction Right that can get exercised by the Preferred/Special security holders. Recall that below US$8.95/share the conversion ratio on those securities goes up, and my bear case is awfully close to that price. If Lumine traded at US$7.00/share, the fully diluted share count could go up by 20% if that Share Retraction Right was exercised! That obviously has a large negative impact on how much I think this business is worth per share for public unitholders. In my mind, the probability that Lumine trades below that dilution threshold is pretty low, but if it gets there then the death spiral of dilution takes hold.

Conclusion

I have no idea where Lumine is going to trade when it gets spun out. Unfortunately, where it trades prior to the Preferred/Special unit conversion can actually impact fair value/share of the Subordinate Voting Shares held by the public. So I suppose there is a decision matrix here. If you own CSU like I do, and you get Lumine shares via the in-kind distribution, then you’re almost perfectly hedged against dilution. If Lumine Subordinate Voting Shareholders get diluted, then CSU picks up that “value”, and you’re relative weight in the two securities (assuming you didn’t incrementally buy/sell either) would lead to almost no loss of aggregate value. There would be some leakage from the Rollover Shareholder group picking up a larger % of Lumine, but it’d be small. In that case, I’m inclined to conclude that this cohort of investors should expect a reasonable return (which for me is at least 9%) on their Lumine shares at US$13/share or below. Above that, I’d probably ditch this stub position in favor of greener pastures because either A) I’m not happy to accept a lower return, or B) I’m not inclined to underwrite those implied assumptions.

For new investors that aren’t CSU shareholders, and have no plans to become a CSU shareholder, it’s a different story. I think Exhibit Q paints the picture perfectly in an extreme scenario. Let’s say Lumine trades at US$10.00/share on Day 1, and you become an investor with the expectation that fair value is ~US$13/share and your IRR is ~12% if you believe in my base case. For some ungodly reason, Lumine briefly trades down to US$4.00/share and the Pref/Special unitholders decide they’ll convert their units into Subordinate Voting Shares at their now-elevated conversion rates. Well now you’ve been diluted by 46% and fair value is only US$7.00 with an IRR of just 5%. You’ve almost certainly just permanently impaired your capital. What’s sort of funny about this is that at US$4.00/share the share count increases so much that the fully-diluted FCF yield would still only be 5.7% vs 4.4% at US$10.00/share. EV/EBITDA would be 14.0x vs 18.5x at US$10.00/share. While I do think it’s very unlikely that Lumine trades at a point where you need to start worrying about this added dilution, it’s a big enough risk that I’d probably wait for conversion to happen before thinking about becoming an investor (or buying more). I suppose in theory, as soon as Lumine is trading above C$9.84/share (something like US$7.35/share) the Mandatory Conversion Date clock starts ticking, and the Preferred/Special unitholders have just 10 days to exercise their Retraction Right. If I had to guess, that would happen almost immediately after the spin out. So the real risk from dilution only exists in the first month of trading, and I can’t imagine the share price could fall that much inside of just 10 days. Against that backdrop, the true downside from dilution is probably limited to 15-20% (not the 47% I used in the draconian scenario above), and the probability of even that happening seems low. Even still, why not wait for that dust to settle, which might be a measly few weeks.

Once the Preferred/Special units convert, and the dilution risk is sorted out, I think there is a remarkable business here that I’d love to own. Let’s say those units convert and the fully-diluted share count stays at 253mn. If you could own a piece of that business at sub-US$13/share that would be great. You’d get to own a durable cash flow generating machine, managed by exceptional people with great incentives, and the added benefit of CSU oversight/resources/network. I think this business will generate high incremental returns on capital deployed, probably be able to deploy a large share of their FCF at those high returns, and likely have better organic growth than what we’ve historically seen from CSU.

As always, I encourage you to reach out if you have feedback, questions, or would like to challenge any of my assumptions. I can be reached at the10thmanbb@gmail.com, in the comments below, or on Twitter.

Really great job on this - love the visuals. Thank you!