Investment Thesis

Constellation’s existing VMS businesses generate a predictable stream of cash flows, and benefit from the diversity of serving dozens (if not hundreds) of verticals across multiple geographies, and hundreds of thousands of customers. Their mission critical software is a need-to-have service, a small share of the customer wallet, and not easily replaced. Most VMS incumbents benefit from not-so-obvious barriers to entry, and a weak competitive playing field. This all leads to sticky customers and low churn. This diversity and low churn limits downside risk for the existing business, which is an attractive feature for investors, but also well understood by the market.

In my opinion, the market primarily misunderstands two things. First, CSU has a world-class management team and a number of competitive advantages that allow them to scale VMS acquisitions at attractive incremental ROIC. In particular, they have perfected a decentralized M&A process, and have a reputation as being great perpetual owners of VMS businesses. I don’t think they get full credit for this. In particular, I think the market is discounting large VMS M&A. Second, my analysis suggests that CSU receives almost no value for new initiatives (CSU 2.0), which means that the market expects the company to distribute a significant portion of FCF to shareholders instead of finding new accretive ways to deploy it. I wholeheartedly disagree.

In addition, CSU could easily increase net leverage given the stability and competitive position of the base business. Pulling this lever could result in significant distributions to equity holders and/or fund new initiatives without really increasing the risk profile of the business. This tends to be a corporate action that rarely gets properly reflected in valuation, even if it’s ultimately inevitable.

This is an extremely high quality business, with a proven core strategy and world-class leadership team and culture. While some uncertainty exists around future growth initiatives, I believe the current price represents a substantial discount to fair value (25%), and more then compensates for this risk.

As always, I encourage you to reach out with feedback or comments if you disagree with any of my analysis. I can be reached at the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

Full disclaimer: I’m currently a CSU shareholder, and have recently increased my weight.

Introduction to CSU

Mark Leonard started Constellation Software (CSU) in 1995. Since then, he’s been on a 25-year acquisition bender of vertical market software (VMS) companies. Today, CSU is a collection of independently managed VMS businesses across dozens of verticals: hospitality, education, healthcare, banking, marine management, libraries, transportation, publishing, utilities, logistics, construction, retail… and the list goes on. Exhibit A shows where they operate, how they classify revenue, and who they serve. In total, I estimate that CSU owns 500 VMS businesses that collectively serve hundreds of thousands of businesses and public sector customers.

There are three things worth clarifying from Exhibit A. First, CSU acquired a company called TSS back in 2013, which predominately sold software in the Netherlands. The TSS deal value was 70-80x the typical CSU transaction, so this single deal meaningfully increased the share of revenue coming from Europe, and increased subsequent growth opportunities on the continent. This explains the growing importance of Europe in the portfolio.

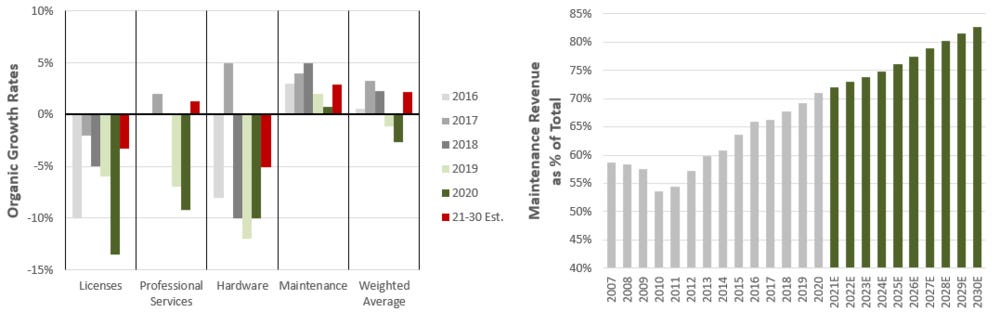

Second, Maintenance/Recurring revenue is some combination of fees for ongoing customer support and SaaS revenue. Delivery of software has obviously changed a lot over time, and even though CSU doesn’t break out the SaaS contribution within Maintenance/Recurring, I suspect it has increased substantially since 2007. Since 2016, when CSU started reporting organic growth by source, License revenue has organically shrunk by 7%/year, while Maintenance/Recurring revenue has grown by 3%/year. What’s interesting about this shift in software delivery method is that licenses generate an up-front fee, while SaaS products spread that revenue stream across many years. As CSU shifts away from Licenses toward the SaaS model, it will have a modestly negative impact on total organic growth, which I believe underestimates the true run-rate. This nuance isn’t a game changer to the CSU thesis, but something to be aware of when assessing their track record and producing forecasts.

Finally, up until 2020 CSU reported revenue from the public and private sector, but those headline figures require some adjustments for reasons not worth getting into here. The headline figures show that 67% of 2019 revenue came from the public sector, and that the public/private split has been roughly constant over time. In reality, public sector customers generated just 49% of 2019 revenue, which is down notably from 57% in 2017. The reason I highlight this will become apparent later.

With those nuances out of the way, no analysis of CSU can begin without understanding the corporate structure (Exhibit B). Functionally, CSU is a holding company. They have a relatively small head office, which oversees six Operating Groups (OGs). CSU just spun out TSS, but ignore that for now. Each operating group manages dozens if not hundreds of Business Units (BUs), where a BU typically represents a single VMS company. On occasion, it might represent two or three. BUs are operationally run as autonomous entities where the BU Manager is free to make all the product and customer decisions as if they were running their own business. The only differences between a BU and a small independently owned VMS business are that BUs get the resources and support of a US$25 bln company, and they typically defer capital allocation decisions to other people in the CSU organization.

CSU is effectively a private equity business with permanent capital, that happens to be owned in a public vehicle. The portfolio companies operate independently, and while they might spend some capital on R&D and S&M, the majority of FCF is pushed up to “capital allocators” to deploy through acquisitions. This makes the suite of existing VMS businesses the perfect cash generating engine for Mark’s M&A machine. Exhibit C shows the split between organic growth and growth from acquisitions and illustrates this dynamic well.

As I think about the value of this business, I’m really trying to answer three categories of questions:

Can the existing portfolio of VMS businesses (cash-generating engine) continue to produce a predictable and growing cash flow stream for decades into the future?

What portion of CSU’s exponentially growing FCF stream can be deployed on VMS M&A, and what incremental return will they earn on that spend? Can the M&A machine operate at full capacity or is it slowing down?

If CSU spends less than 100% of FCF on VMS M&A, what else can they do with that capital?

The Cash-Generating Engine

CSU’s core strategy is simple: acquire small established owner-operated VMS businesses with a dominant position in a vertical, provide them with the support and resources of the mothership, let them operate with autonomy, and #neversell. They also prefer to acquire products that are A) mission-critical to their customers, and B) a small share of the customer wallet (typically 1%).

One consequence of acquiring established VMS businesses with a dominant market share is that the end market tends to be relatively saturated. Organic growth ends up being low relative to many other software categories, which helps explain CSU’s measly 1.5-2.0% organic growth CAGR over the last decade.

Another reason that organic growth tends to be low is that addressable markets for VMS products are typically small. Unlike horizontal market software (HMS), VMS is tailored to the needs of one niche, and one niche only. At the HMS extreme is Microsoft Excel, which can be used by literally anybody: individuals, corporations, governments; big or small; and, in any industry. It is a great generic spreadsheet tool with an enormous addressable market. By getting the product/market fit and execution right with an HMS product, a vendor can realize incredible top line growth for decades. Not so with VMS. At the VMS extreme is a company like Trancite (a CSU BU), which sells diagramming tools for crash scenes to police departments. Trancite products are effectively useless to anyone that isn’t evaluating crash scenes. No matter how dominant Trancite is in that vertical, the market is only so big.

The upside of small addressable markets is that competition tends to be limited to other small developers. Microsoft, Google, or some large VC-backed entity aren’t going to bother trying to take share in a market that only does a hypothetical $300 mln in revenue per year. As a result, competition tends to come from smaller, less sophisticated, and more cash constrained software companies. The R&D and S&M spend that any small new entrant would ever commit to building a competing product is low, and incumbents that have been building the product for 10 years have the cumulative benefit of all that development and marketing spend behind them. If 50% of these line items were capitalized instead of expensed, it would show that the barrier to entry in many small verticals is quite high. This is great for the established incumbents that CSU owns.

The downside of a small addressable market is that it is difficult to realize the scale economies that successful HMS products do. I lifted this Andy Rachleff analogy from an a16z piece:

“If you address a market that really wants your product — if the dogs are eating the dog food — then you can screw up almost everything in the company and you will succeed. Conversely, if you’re really good at execution but the dogs don’t want to eat the dog food, you have no chance of winning”

Good VMS businesses have identified the dogs and are giving them curated dog food. The Russian mastiff gets Russian mastiff food (probably an entire cow), the vegan poodle gets Wild Earth, and the terrier gets Kibbles n’ Bits. Trancite is feeding curated food to the German shepherds of the police force, which is great because product/market fit is strong, but bad because they can’t sell the same product to terriers, let alone humans. As a result, I see no evidence of scale economies when looking at cost items that principally reside within a BU like R&D and S&M.

In these small saturated markets, the best way to generate above-average profit growth is to take share from competitors. I generally view Maintenance/Recurring revenue as the best barometer for the health of CSU’s existing businesses, and up until 2017, the company disclosed the four drivers behind Maintenance/Recurring organic growth (Exhibit D). Attrition from lost customers and lost modules is equivalent to customer churn, which has historically been 5-9%/year. Including price increases, we get gross dollar churn of just 0-4%. I tried to find industry benchmarks for churn rates, and although it’s dated, Clement Vouillon published a great Medium article that aggregated data from multiple sources. What I found is that CSU has lower customer and revenue churn than the average, which implies that they might be taking share from competitors. Adding back growth from new business, CSU ends up with Maintenance/Recurring organic growth rates in the ~mid single digits (2020 was obviously impacted by COVID). This organic growth requires little incremental capital, which results in increasing ROIC, even after we factor in attrition from License and Hardware revenue (since 2010, organic Maintenance/Recurring Revenue has increased by $454 mln/year, while total capital expenditures at CSU were just $157 mln).

The below-average churn rates and increasing ROIC indicate that CSU has some competitive advantages in the VMS space. I think these can be distilled down to A) a first mover advantage leading to high switching costs, and B) a decentralized organizational structure.

First mover advantage leads to high switching costs

In the semiconductor world, Moore’s law observes that transistor capacity doubles every two years. As a result, every two years there is a new node of semiconductor products, but not everyone reaches the node at the same time. Being there first is a big advantage because you can have faster and more powerful chips than your competitors, and therefore earn economic rent. For 50 or 60 years, Intel was always the first company to reach the next node. That’s a long period of consistently being number one, and it’s worth understanding why. In episode 149 of Invest Like the Best, Gavin Baker explains why he thinks Intel was the market leader for half a century, which I believe is also applicable to the VMS industry:

“Modern semiconductor manufacturing is the closest thing to magic in the real world. We are manipulating atomic particles. It’s amazing what’s happening. It’s as much art as science. And the reason Intel had the lead so consistently is that it’s almost like cooking, where you come up with a recipe for a new node and you have to test it and iterate it, and it depends on what you did before. And just like a cook needs to see what the brownie or cake tastes like, and hone in on the exact right recipe… that is modern semiconductor manufacturing [once you’re ahead, you’re always ahead]. There is an element of art and making bets and trial and error“

Many of CSU’s VMS business have customized products that improve over time through an iterative process that relies on customer feedback. In my view, customized VMS products improve much the same way a cook improves a brownie recipe: the vendor sells Version 1.0, customers try it, they provide feedback, and the vendor uses that feedback to create Version 2.0. By Version 13.2.A, the vendor has it nailed. They are so engrained with their customers that they can almost anticipate customer needs before the customer can (which leads to even better products). For a new entrant to be competitive, they need to work through all of that trial and error internally before launching Version 1.0 of their competing product. That’s really hard to do successfully. If the VMS business is anything like semiconductors, being first to a “node” matters.

Enterprising vendors with deep customer relationships and continuously improving products have also built a level of trust with their customers that is hard to replicate. So even if a new entrant has a similar quality product on Day 1, why would a customer switch if they were happy with - and trust - the current vendor? These are products that might represent 1% of customer revenue, so any potential savings are minimal. It is difficult to justify the risk of switching for mission-critical processes. This is especially true for small customers where an owner-operator is responsible for making the decision. These owner-operators have time constraints, and have to weight the return on their time from switching software vendors versus the return on their time from doing anything else. Anything else usually wins.

The other great thing about selling mission-critical software is that it is a need-to-have, not a nice-to-have. It is not discretionary spending. In 2009 and 2020, CSU realized organic growth of -3.0% and -2.6% respectively. Customer churn on Maintenance revenue in 2008/09 from Exhibit D didn’t even budge. It is truly remarkable that in two really challenging years for CSU customers, very few churned off.

Lastly, I highlighted earlier that roughly half of CSU’s revenue comes from customers in the public sector: municipalities, school boards, police departments, etc. Incentives in the public sector are notoriously absent and/or misaligned, so the impetus for a salaried government employee to lobby for a change in software vendor rarely exists. Why introduce a new project and implementation risk if you don’t have to? Even if a change is desired because of vocal constituents or frustrated employees, the selection and implementation process for new software in the public sector is painfully slow. As long as these customers are even “moderately happy” with a product, I suspect they’ll avoid changing vendors out of convenience, and because CSU probably beats moderately happy, the customer churn rate from this base must be close to 0%. I went out of my way earlier to highlight that revenue from public sector customers fell from 57% in 2017 to 49% in 2019, likely as a result of disproportionate M&A in the private sector. In my mind, it’s no coincidence that organic Maintenance/Recurring growth fell over that period – the stickiest customers represent a smaller portion of the business. Nevertheless, public sector customers still make up a large portion of the total, which I view favorably.

Decentralized organizational structure

Mark believes that one of CSU’s greatest advantages is organizational structure, particularly the idea of human-scale business units. It pains me to take the easy way out with a 2-page quote, but Mark describes this advantage so much better than I ever could, so…

“We seek out vertical market software businesses where motivated small teams composed of good people, can produce superior results in tiny markets. What we offer our BU Managers is autonomy, an environment that supports them in mastering vertical market software management skills, and the chance to build an enduring and competent team in a ‘human-scale’ business. While we have developed some techniques and best practices for fostering organic growth, I think our most powerful tool is using humanscale BU’s. When a VMS business is small, its manager usually has five or six functional managers to work with: Marketing & Sales, Research & Development ("R&D"), Professional Services, Maintenance & Support and General & Administration. Each of those functional managers starts off heading a single working group. If the business leader is smart, energetic and has integrity, these tend to be halcyon days. All the employees know each other, and if a team member isn't trusted and pulling his weight, he tends to get weeded-out. If employees are talented, they can be quirky, as long as they are working for the greater good of the business. Priorities are clear, systems haven't had time to metastasise, rules are few, trust and communication are high, and the focus tends to be on how to increase the size of the pie, not how it gets divided. That's how I remember my favourite venture investments when I was a venture capitalist, and it's how I remember many of the early CSI acquisitions.

That structure usually suffices until there are perhaps 30 to 40 people in the business. At that stage, some of the teams - perhaps R&D if the product is rapidly evolving or has high needs for interfaces or compliance changes - must grow beyond the five to nine optimal team size. If the head of R&D in this example is brilliant and is willing to work hours that are unsustainable for most of us, he may be able to parse out tasks for each of the team members despite the increased team size. He may be able to judge the capabilities and cater to the development needs of each of his direct reports. He may be able to recruit excellent new employees, and he may be able to manage the demands and trade-offs required to coordinate with the other functional managers. The more likely outcome, is that the R&D manager isn't a brilliant workaholic and cannot cope as the team size exceeds double digits. Instead, he'll break his team up into multiple teams. A new level of middle managers will be born, with all the potential for overhead creation, politics, and bureaucracy that comes with another tier of middle managers.

The larger a business gets, the more difficult it becomes to manage and the more policies, procedures, systems, rules and regulations are generated to handle the growing complexity. Talented people get frustrated, innovation suffers, and the focus shifts from customers and markets to internal communication, cost control, and rule enforcement. The quirky but talented rarely survive in this environment. A huge body of academic research confirms that complexity and co-ordination effort increase at a much faster rate than headcount in a growing organisation. If the BU is small enough, and has a competent BU manager who has several years experience in the vertical, and good functional managers, then he/she will be able to cope with complexity for a while, making the right calls to optimise organic growth as the business grows. The challenge of running a BU of this size is human-scaled.

As a BU becomes larger (by our standards, that’s greater than 100 employees), I worry that even an extraordinarily brilliant and energetic manager, who has been in the vertical and the BU for a very long time, and is surrounded by a strong team that he/she has selected and trained over many years, is going to struggle to steer the business to above industry average organic growth. No one wants to admit that they’ve hit their limit. Some BU Managers lack the humility, some lack the courage, and most lack the time for reflection, to notice that their task is getting too large, and the sacrifices are getting too great. This is the point at which our Operating Group Managers or Portfolio Managers can provide coaching. If a large BU is not generating the organic growth that we think it should, the BU manager needs to be asked why employees and customers wouldn't be better served by splitting the BU into smaller units. Our favourite outcome in this sort of situation is that the original BU Manager runs a large piece of the original BU and spins off a new BU run by one of his/her proteges. Ideally, he/she has been grooming a promising functional manager who’ll be enthusiastic about running and growing a tightly focused, customer-centric BU.

This dividing of larger BU’s into smaller units is rare, but not unknown, in other large companies. One of the HPC’s that we studied was Illinois Tool Works Inc. (“ITW”). It has hundreds of BU’s. We began following the company from afar in 2005. The most relevant period in ITW’s history for CSI was the tenure of John Nichols. Nichols began consulting to ITW in 1979, and appears to have been the primary author of its decentralisation strategy. He was CEO as the company went from $369 million in revenues in 1981 to $4.2 billion in 1995 ($6.7 billion in today’s dollars). Prior to Nichols's tenure, ITW had acquired only 3 businesses. During his tenure, ITW aggressively acquired and often split the larger acquisitions into smaller BU’s. ITW had 365 separate operating units by 1996 when Nichols retired. I’m sorry I didn’t reach out to some of the ITW employees and ex-employees until 2015. When I did talk with one of the senior managers, he said (I’m paraphrasing) “Something wonderful happens when you spin off a new business unit.” … “With a clean sheet of paper, the leader only takes those he needs. They set up in an open office with good communication and no overheads. They cover for each other. They leave all the bureaucracy and the crap behind”. I did record a couple of verbatim quotes from that conversation: "Don't share sales, R&D, HR, etc. because the accountants never get the allocations right and the business units always treat the allocated costs as outside their control", and "When you get big you lose entrepreneurship".

Volaris and TSS regularly divide their larger BU's into smaller BU's that focus on sub-segments of their markets. Volaris feels strongly that splitting larger BU’s into smaller ones allows more targeted products and services that differentiate their offerings from their more horizontal competitors. Harris has very successfully acquired multiple BU's in the same industry and run them independently rather than combining them into one BU. Both tactics forego obvious and easily obtainable benefits from economies of scale. We think we get something valuable when we constrain BU headcount, but it isn’t a panacea for all of our organic growth challenges”

In 2013, CSU conducted an internal study to assess if the size of a BU is negatively correlated with performance. They regressed BU size (x-axis is headcount) with BU performance (y-axis is a blend of growth and profitability), and found that r-squared was close to zero. The takeaway was that size had not yet negatively impacted performance, which is interesting considering how adamant Mark has been about keeping BUs small. Nevertheless, I agree with Mark’s logic that human-scale business units likely maintain an entrepreneurial culture that results in higher customer loyalty, continuously improving products, lower overhead, and better retention of talented people. Combined with the added resources and support that CSU can provide to their VMS businesses, this sustained entrepreneurial environment is likely a key driver behind historically low churn and increasing ROIC.

In my view, the risk is not that other large companies approach decision making in the same decentralized way, but rather that CSU loses the ability to operate in such a decentralized manner. If that were to happen, I suspect churn would go up, pricing power would diminish, and ROIC would fall.

There is some evidence that churn has gone up since 2013, and organic growth has certainly slowed. There are multiple explanations as to why, some of which I’ve already discussed, but one might be that CSU is bumping up against a size threshold that is starting to impact performance. Maybe it’s increasingly difficult to operate human-scale BUs within an exponentially growing company (revenue is 3.0x higher today than it was in 2013). This might explain the decision to spin off TSS – hitting the reset button on one OG would be a good way to test a hypothesis that smaller entities enjoy improved performance. If TSS is successful as a stand-alone entity, I don’t see any reason that Volaris wouldn’t also be spun-out in a few years. This would have the dual benefit of scaling down CSU, and freeing Volaris from any bureaucracy-creep that might have seeped in over the last decade.

Losing the human-scale advantage is a significant risk to monitor, but most of the data suggests that CSU continues to benefit from this structure today, and there are clearly levers they can pull to maintain this structure over time.

Tying it all together

CSU has a diverse set of VMS businesses that operate in relatively mature markets where barriers to entry are high for small independent software companies, and addressable markets are too small to invite competition from any behemoth. Growth in these markets tends to be relatively low, and there is little opportunity to realize scale economies. Nevertheless, weak competition and high switching costs result in cash flow streams that are predictable and stable. Human-scale business units help maintain an entrepreneurial spirit that likely helps CSU gain share in their verticals and generate modest organic growth over time. The diversity in verticals and geography also insulate CSU from the ebbs and flows of the economic cycles in any one market, and reduces cash flow volatility.

This cash generating engine has powered CSU’s M&A machine since 1995, and there is compelling evidence to suggest that this will continue to be the case for decades to come.

The M&A Machine

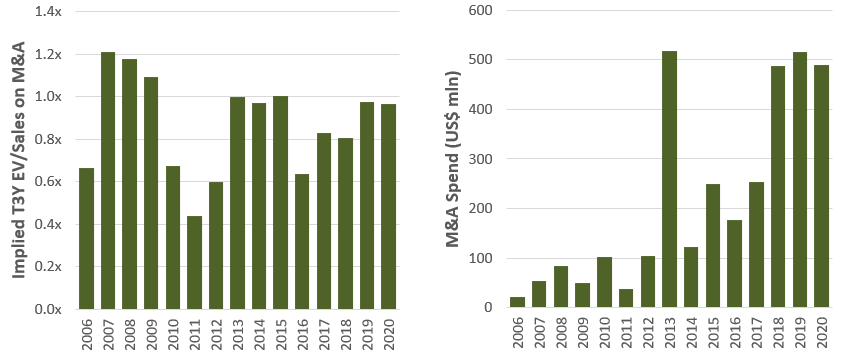

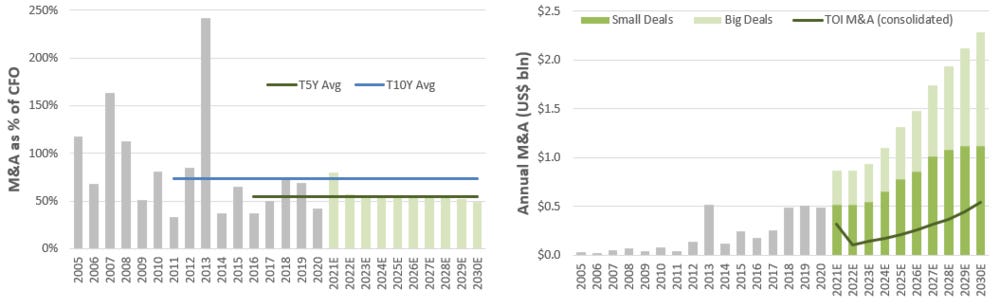

This is obviously the most interesting part of the story, and the place where I believe the range of future outcomes is widest. The best place to start is a look-back on what CSU has accomplished so far. The company reports revenue growth from M&A, and total M&A spend, which helps me back into an average EV/Sales multiples for all acquisitions in a year. Since 2006, CSU has increased M&A spend from $20 mln to >$500 mln, and yet the average transaction multiple has been more-or-less flat (albeit volatile). Given that margins at the corporate level have generally increased, it’s safe to conclude that they are not seeing diminishing marginal returns.

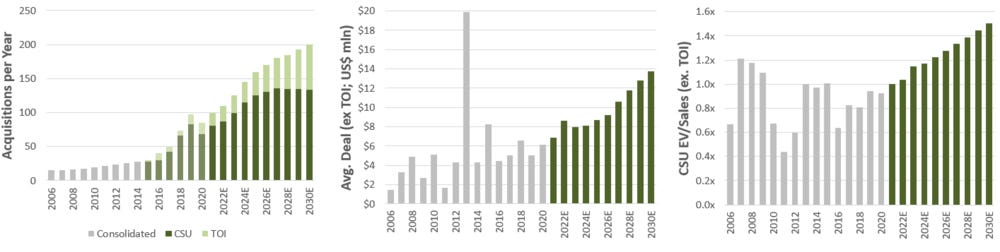

What’s more impressive is the absolute level of the EV/Sales multiple. I estimate that a 1.0x EV/Sales multiple is equivalent to a ~25% ROIC at the operating entity level. In my view, the primary reason CSU has been able to earn such a consistently high return on an exponentially growing M&A budget is that they’ve managed to keep average acquisition size small. Through a combination of management commentary, guesswork, and channel checks, I’ve managed to plot an estimate of historical acquisitions completed by CSU per year. From there I get an implied deal size, and Exhibit F shows that deal size has been more-or-less constant at ~$5 mln.

All else equal, as deal size gets larger, incremental ROIC falls (EV/Sales goes up). Exhibit G shows the historical relationship between deal size and acquisition multiple for CSU. I’ve anecdotally heard that acquisitions of VMS businesses over US$20 mln that are growing the top-line at mid-single-digits typically sell for 8-9x EBITDA (~2.0x Sales), which roughly lines up with the logarithmic relationship we see in Exhibit G. The Topicus acquisition was done at €217 mln, on 2020 revenue that probably works out to ~€115-120 mln, implying 1.8-1.9x Sales. There aren’t enough data points to know how strong this relationship truly is, but it’s a great starting point for understanding future returns.

By 2024, CSU will have enough internally generated cash flow to enable $1.0+ bln of annual M&A. To combat diminishing marginal returns, they would need to execute on at least 150 deals per year. By the end of the decade, they would have the capacity to deploy many billions through M&A annually, which would require 300+ small deals to keep deal size <$10 mln. I don’t think this is likely, and it appears that CSU will be deploying more capital on large M&A and new initiatives as a result. Nevertheless, the company has two competitive advantages that should help them scale small VMS M&A well into the future: a decentralized M&A process, and reputation/culture.

Decentralized M&A

During the first decade that Mark managed CSU, he was largely responsible for making all of the acquisition decisions. In 2006, when the company hit 30 BUs, he delegated most of this task to six or seven Operating Group Managers (OGMs). Large acquisitions were still vetted by Mark and the team at head office, but most small capital allocation decisions became decentralized. Over the next decade, OGMs built and trained their own M&A staff, and further delegated some responsibility for capital deployment to Portfolio Managers (of which there might be 5-10 at each OG). By 2016, there were 26 OGMs and Portfolio Managers that spent >50% of their time on M&A, and another 60 full-time M&A professionals spread across CSU. In 2018, CSU gave OGMs the autonomy to approve acquisitions up to $20 mln, pushing more of the capital deployment responsibility down the chain. I don’t have any current data, but if I had to guess, CSU probably has 35-40 OGMs and Portfolio Managers that spend >50% of their time on M&A today, and another 100-120 full-time M&A professionals spread across the OGs.

Many of the ~150 people responsible for M&A once managed a VMS business. They know the customers and competitors, they have deep relationships, and they understand the products. Who better to curate a wish list of targets then someone intimately familiar with a vertical? Many other M&A professionals work within an OG or BU, not at head office. For example, the Jonas OG recently posted for an M&A associate to work specifically in their Club & Hospitality Division. As a result, most M&A professionals get to know the customers, the competitors, and the product, better than a generalist tasked with covering all markets. BU leaders in the Club & Hospitality group also help identify and source acquisition targets for that specific M&A team, which puts the capital deployers and the targets within one degree of separation. In my view, this all helps create a very wide funnel of actionable prospects. As CSU grows by adding more BUs and verticals, more M&A staff inevitably follow (whether outside hires or promoted BU Managers), which helps make decentralized M&A scalable.

After a prospect enters the funnel, CSU has developed a very systematic and data-driven process for filtering and ultimately acquiring some of those businesses. Like many great companies, the CSU management team clearly subscribes to the idea that you can’t manage what you don’t measure, and they have gone out of their way to measure key operational and financial metrics at all of their portfolio companies. CSU has probably completed 500+ acquisitions in the last twenty years, which generate lots of data across verticals and geographies. As a result, the company is sitting on a large and growing proprietary data set. This data set is a key input to the quantitative capital allocation process:

“Whether it is a neophyte investment champion arguing that a particular acquisition is ‘special’, or a senior executive being tempted by a large acquisition, we have enough data to make the discussion rational, not emotional. We all know whether the key assumptions are being pushed to the 55th or 95th percentile of our historical distributions.”

Mark has institutionalized mutually exclusive collectively exhaustive scenario modelling (MECE). As I understand it, M&A folks probability-weight cash flows from four different scenarios, using proprietary data sets to understand the range of outcomes. MECE allows everyone to “use a single hurdle rate across all investment prospects, even if the investments have very different risk profiles”. By combining a single hurdle rate with definable and quantitative inputs and outputs, CSU has reduced much of the subjectivity involved in the capital allocation process. Mark found a recipe that works, and then created a systematic machine to democratize who can participate in M&A decisions. This is a critical contributor to the success of decentralized M&A, in my opinion.

This system of thinking and analysis seems to have successfully propagated to each newly minted capital allocator in the company – if it hadn’t, incremental ROIC would be falling. That propagation is only possible because of how much thought is put into M&A education. CSU conducts post-acquisition reviews (PARs) on the first anniversary of every deal. These PARs are rooted in the belief that “an investment only becomes a lesson if we diligently track its post-acquisition performance and take the time to analyze the outcome while the investment is still fresh in everyone’s mind”. With CSU executing upwards of 50 deals per year for many years now, there are lots of PARs happening all the time, and lots of opportunities for existing and future capital allocators to learn. The Operating Groups also host learning summits where leaders and other talented employees from all the BUs get together and discuss best practices. In my view, new part-time capital allocators have incredible resources to guide and educate them.

Without the scalable deal funnel, proprietary data sets, quantitative framework for allocating capital, and the education process, it is unlikely that CSU would have been successful at decentralizing M&A. I see no compelling reason that CSU couldn’t continue leveraging this structure to do 200 deals per year by 2030 (consolidated to include TOI).

Reputation and Culture

Although difficult to prove without a large data set, I suspect CSU pays slightly less for acquisitions than other competitors in the space, all else equal. There is too much anecdotal evidence to ignore, like this, and implied acquisition metrics are lower than what I hear from most private equity investors in the same space.

One reason that they get better returns on M&A is that they try to avoid competitive bidding processes. They identify and source deals directly through a growing network of BUs, but more importantly, they have a reputation as being a great owner of VMS businesses. Entrepreneurs looking to sell their business have a long list of reasons to approach CSU before any other buyer, most of which are rooted in a culture that fosters personal and professional growth, provides autonomy, embraces meritocracy, and pays for performance.

I think it was Peter Drucker that first said “culture eats strategy for breakfast”, and corporate culture is clearly a CSU advantage. Mark once wrote:

“My motivation is to help create a company where worthy people succeed. Whether they join us with an acquisition or are hired from the outside, I want to support and encourage employees who work hard, treat others well, continuously learn, and share best practices. I try to make sure that sycophants, spin-doctors, and mercenaries don’t survive in Constellation’s senior ranks. Harder, but not impossible, is helping identify and remove hidebound managers who rely upon habit and folklore to run their businesses rather than rational enquiry and experimentation. Constellation is as close to a meritocracy as I have experienced. I hope it will continue to provide an environment where entrepreneurs and corporate refugees can invest their lives and their capital and thrive.”

Glassdoor reviews for CSU and their OGs show that they all rank above average in every category. In some cases, the OG scores exceptionally high, like Harris, which was named a Best Place to Work in 2020. CSU and the OGs have shared more than 25 testimonial videos, many of which come from previous owners of a business CSU acquired. Some common themes in these testimonials seem to be:

The acquired business can continue to operate autonomously and maintain their own subculture. This is important to sellers that want to continue running the business post-sale.

There are exponentially more personal and professional growth opportunities within CSU than as a standalone entity. Employees of VMS businesses that want to progress their careers will find multiple opportunities outside of their specific BU. This increases employee satisfaction and retention.

Access to CSU data and the peer network is invaluable in helping to grow the business in ways that might not have been possible as an independent software company. This also increases employee satisfaction and retention.

CSU is a perpetual owner of VMS business, which means that employees at acquired businesses get stability. They don’t need to worry about the business changing hands again and what that might mean for their jobs.

CSU can turn around an offer quickly – no waiting a year to figure out the fate of the business.

CSU also pays well, and Mark has no qualms with creating millionaires, so long as that wealth gets invested in CSU shares. In 2015, Mark said that there were more than 100 employee/shareholder millionaires, and he hoped that number would be five times larger by 2025. The company’s employee bonus plan requires that all employees who reach a threshold level of compensation invest a portion of their compensation in CSU stock that vests over four years (interestingly, this stock is purchased in the open market). In practice, the holding period tends to be much longer. Depending on the position, 25% to 75% of an employee’s after-tax bonus must be invested in CSU stock, and more than 3,000 employees earn above the threshold where this kicks in. That makes for a lot of insider ownership. Compensation is tied explicitly to individual and operating group performance, but wealth is tied to success of the organization. This pay-for-performance culture, where everyone rows in the same direction, is attractive to a lot of potential CSU targets.

A great reputation is a fantastic marketing tool, because it increases the probability that a small VMS owner will unilaterally approach CSU, as opposed to pursuing a competitive bidding process. But a more important reason that reputation matters is that price is rarely the only criteria that a VMS seller contemplates. Most small VMS businesses are owned and operated by a founder with a small team of people, many of whom become like family. The seller wants these people to have a permanent home, maintain autonomy, and have opportunities to grow. Many sellers probably want most of those things for themselves as well. CSU’s philosophy, decentralized model, track record, and resources make it an obvious fit for these sellers. So even if CSU offers a price that is lower than a competitive bidding process might have garnered, it still might be the preferred fit for owner-operators that think long-term and want to stick around post-sale.

While it’s still too early to know for certain, I suspect that a great reputation as a perpetual owner of VMS businesses should help with large M&A as well.

M&A Competition and VMS Runway

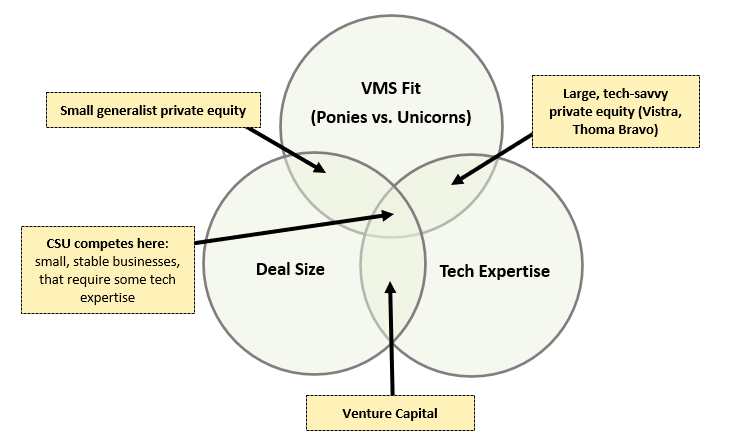

In 2014, Jerry Neuman wrote an entertaining piece titled Betting on the Ponies: non-Unicorn Investing, and while he certainly has a penchant for dramatic flair, a lot of what he said has stuck with me over the years. Marc Andreesen once said that 8% of a16z’s portfolio companies generate most of their economic return, while the remainder basically lose money. VC firms hunt for unicorns. By design, they are not interested in mature software businesses with small addressable markets, and therefore don’t compete directly with CSU in the M&A arena.

If Facebook was a unicorn, then the run-of-the-mill VMS businesses that CSU pursues are certainly ponies. Trancite? Jonas Construction Software? Pony 1, and Pony 2.

So, who competes to purchase ponies? One obvious group is private equity. Fortunately for CSU, a significant portion of all private equity AUM is managed by generalist firms without the depth of software expertise required to be successful in the VMS space, or to be attractive homes for VMS sellers. Most private equity firms also ultimately sell their portfolio companies and are not permanent homes for a VMS business, which isn’t appealing to many VMS sellers. There are some tech-focused private equity firms that may have long holding periods, but the best ones fall victim to their own success. A great early track record leads to AUM growth, and great firms like Vista Equity Partners and Thoma Bravo have grown AUM significantly over time. Combined, these two firms have completed ~750 acquisitions, and have around US$150 bln in assets. Average deal size today must be somewhere north of US$100 mln and growing. CSU’s average deal size is US$5 mln. One day, CSU might compete with these firms, but they certainly aren’t today. On the other end of the spectrum are small tech-focused private equity firms that might not have the scope, resources, access to talent, or reputation of CSU. These aren’t meaningful competitors either. The sweet spot is a miniscule corner of the universe that includes the likes of ESW Capital, who aren’t so big that they only chase large deals, but aren’t so small to be resource constrained. CSU estimates that there might only be a dozen or so tech-savvy private equity firms like this in North America who they consider to be meaningful competitors.

Lastly, some corporates have a similar M&A strategy, and might compete with CSU from time to time. Roper Technologies (ROP) is an example that comes to mind, but the overlap in that particular case probably isn’t great. There are very few corporates like ROP, and many of them are dedicated to only a handful of verticals and/or are too big to be considered serious competitors.

To summarize, a core part of CSU’s strategy is to look for ponies, in a small snack bracket, that require some tech expertise to identify, purchase, and add value to. As a result, CSU has traditionally competed in a small corner of the market.

In 2017, Forrester estimated that there were more than 100,000 independent software companies globally, growing at 25%/year. That’s a lot of targets, even if I only screen for small ponies. CSU keeps an internal database of VMS acquisition prospects, which they are constantly refreshing as businesses are acquired and new ones are identified. The database filters for companies that meet the CSU criteria, which includes some combination of:

#1 or #2 market share, or a strong competitive edge

Revenue of at least $5 mln

Hundreds or thousands (not dozens) of customers

Management teams that can remain in place

Consistently profitable

Some portion of that database gets acquired every year, and CSU estimated that their coverage ratio (% of those sold that come to CSU) is generally around 30%, even as the number of acquisitions has grown exponentially. This tells me that the database is quite large and growing over time. If 5-10% of VMS businesses in the prospect database were sold every year, it would imply that the database has 3,500-7,000 prospects today. This supports my thesis that the runway for VMS acquisitions is extremely long, even in the small corner of the market that CSU competes.

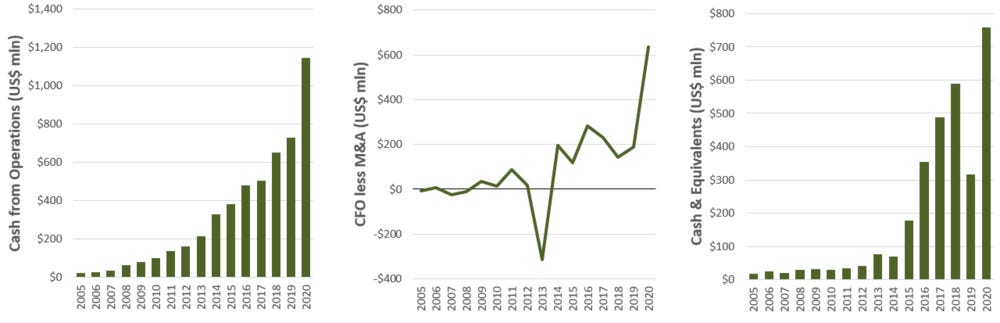

M&A Constraints & Evolution

Even though the VMS market is large and fragmented, and CSU has some competitive advantages that allow them to execute on lots of deals and achieve above-average IRRs, it is definitely getting more difficult to keep the machine running at full speed. Exhibit I shows that CSU’s operating cash flow has grown exponentially over time. Pre-2015, CSU had no problem deploying most of that cash on M&A, so cash barely accrued on the balance sheet. Post-2015, CSU consistently spent less than 100% of CFO on acquisitions, and cash balances grew significantly. The company ended up paying a large special dividend in 2019, because they just couldn’t find enough acquisitions that exceeded internal hurdle rates for new investments.

One issue is that CSU has historically maintained a high hurdle rate – which is obvious considering EV/Sales hasn’t really crept above 1.0x. Dropping the hurdle rate would no doubt result in more M&A, but Mark has been hesitant to do so:

“Obviously we could do more organic growth Initiatives (and acquisitions) if we dropped our hurdle rates. We observed in early 2015, however, that lowering hurdle rates had historically been far more expensive than we originally thought. We analysed the weighted average expected IRR’s for each of our acquisitions by year from 1995 to early 2015 and compared them with the prevailing hurdle rate we were using when the acquisitions were made. During that twenty year period we made three changes to the hurdle rate, one up, two down. The weighted average expected IRR for each vintage (e.g. all of the acquisitions done in 2004) of acquisitions tended to drop or increase to the newly implemented hurdle rate. Said another way, when we dropped our hurdle rate, it dragged down the expected IRR’s for all the opportunities that we subsequently pursued, not just those at the margin. We try to capture this idea by saying “hurdle rates are magnetic”. It now takes a very brave soul to propose a hurdle rate drop at CSI.”

Nevertheless, to deploy more capital, CSU dropped the hurdle rate on large acquisitions in 2019, while keeping the legacy hurdle rate intact for everything else. At the time, they defined a large transaction as something requiring an equity check in excess of US$100 mln, which is 20x CSU’s historical average deal size. In the 2021 President’s Letter that was published yesterday, Mark acknowledges that CSU will need to pursue large acquisitions in an effort to deploy more capital. His target in the short-term is to execute on 1-2 large deals/year. Going forward, I expect incremental ROIC to begin falling as larger deals get executed that dilute some of the high returns earned on small acquisitions. However, this should also allow CSU to deploy a greater portion of CFO on acquisitions. The Topicus.com acquisition is a good example: the deal value was US$265 mln at ~1.8x 2020 revenue.

Tying it all together

The runway for VMS acquisitions is long, even in the small corner of the market that CSU targets. The company has two unique advantages that help them deploy cash and earn exceptionally high incremental returns on small M&A, but scale has started to become a constraint. To deploy more capital, CSU has lowered hurdle rates for large investments and plans to pursue much larger deals, which should start to drag average incremental ROIC down, even if they can ultimately execute 200+ deals a year. Nevertheless, I’m fairly confident that incremental ROIC will remain much higher than CSU’s cost of capital well into the future, even as they deploy greater and greater amounts of CFO.

CSU 2.0

Despite lowering hurdle rates on large deals, and more seriously pursuing large acquisitions, I think CSU will find it challenging to deploy 100% of their exponentially growing cash flow every year on VMS acquisitions. For many years now, Mark has indicated that one day CSU might have to branch out from the VMS space in order to keep deploying capital, and his most recent letter to shareholders indicates that they have finally reached this tipping point. In particular, he notes:

“In parallel with our established and growing small and mid-sized VMS practise and our nascent large VMS practise, we are trying to develop a new circle of competence. We are seeking attractive returns, a sustainable advantage, and the ability to deploy large amounts of capital outside of VMS. That will require highly contrarian thinking and is likely to be uncomfortable in the early going. Hopefully, we have built enough credibility to warrant your patience as we explore new and under-appreciated sectors.“

This is no easy feat, but if anyone can do it, I’d put my money on the team at CSU. Unfortunately, this is a known unknown. It’s going to be really difficult to assess strategy, capital deployment opportunities, and potential returns without knowing what CSU plans to do next. In many ways, this opportunity represents a real option. The two big unknowns are A) how much cash can CSU deploy, and B) what incremental ROIC can they earn on this cash. See the Valuation section for how I think about building this in to the base case.

Performance

In the last ten years, CSU has grown Revenue and EPS at CAGRs of 23% and 42% respectively. Both ROIC and ROE exceeded 40% in 2019 and have increased substantially since the early 2000’s, despite the growing cash balance. Mark’s strategy – and execution of that strategy – is clearly working.

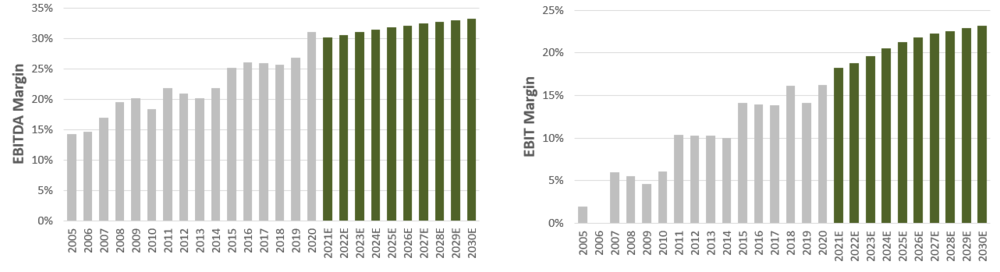

CSU’s EBITDA margin has also steadily increased over time (Exhibit K). Under the decentralized model, very few expense lines benefit from scale, but Professional Services and G&A are the exception. You can find my linear regressions on each expense line in the model, or just take my word for it. If historical performance is any indication, CSU should continue to benefit from scale in these two categories. The other driver behind increasing EBITDA margins is that the contribution from Hardware sales has decreased significantly in the last decade (from 12% to 5%), and margins on hardware are lower than the rest of the business. This is another theme that’s likely to continue, and provide some support for margin expansion.

Financial Position

In 2015, Mark wrote:

“We haven’t decided yet where we stand on using leverage, other than that we want to avoid using short term debt to finance long term assets, or using long term debt that is unreliable.“

He clearly has an aversion to most types of debt, which explains why the only leverage CSU has is a set of 2040 covenant-lite debentures and some non-recourse debt at a couple of subsidiaries. The debentures were issued to pay down bank debt that CSU took out to acquire TSS back in 2013, but otherwise CSU hasn’t needed any external funding, debt or otherwise. As a result, the company has a largely underutilized balance sheet, with negative ND/EBITDA. In all fairness, CSU has historically generated more cash than they know what to do with, which explains the regular dividend and sporadic special dividends.

Despite low leverage today, Mark does indicate that under the right circumstances it makes sense to utilize the balance sheet:

“Financial leverage is a tool that can have a profound impact on ROIC. Some HPCs have whittled down Invested Capital as a percent of Total Capital by borrowing to pay dividends, repurchase shares, and/or make acquisitions. This has helped them generate higher ROIC’s. One of the HPCs has returned their entire Invested Capital to shareholders, and hence generates an infinite ROIC. If covenant-free long tenured debt is available at a lower after tax cost than equity, then this kind of capital structure is attractive.“

I see two potential outcomes here. If the company can build a new circle of competence through CSU 2.0 with new opportunities for capital deployment, the balance sheet capacity could help fund this new business. If they can’t effectively build out a new circle of competence, or if capital deployment opportunities don’t absorb all of their FCF, this balance sheet capacity could ultimately lead to increased distributions to equity holders. Either way, I expect it will be utilized to the benefit of equity holders over time.

It’s worth noting that CSU recently announced their intention to axe special dividends as they pursue large VMS acquisitions and new initiatives. Mark clearly believes that CSU can deploy most of their FCF.

Management & Governance

To believe in the success of CSU 2.0 or the VMS acquisition strategy is to believe in management and culture. There is no better way to do that than by reading the President’s Letters on the CSU website. Having read through these letters, and ample other literature, here are my biggest takeaways:

For an organization of its size, CSU embraces a meritocratic structure more than any other company I’ve come across. They empower great people at any level to make decisions and challenge the status quo.

The leadership team leads by example. They aren’t afraid to experiment, make mistakes, learn from them, and share those lessons.

The emphasis on incentives is enormous. Employee stock ownership is high and growing. Mark owns nearly US$600 mln in CSU stock, and the remaining directors cumulatively own US$900 mln. There are also a couple hundred employees that own more than US$1.0 mln in shares, and over 3,000 employees who are required to invest a portion of their after-tax bonus in CSU stock with a minimum 4-year vesting period.

They think long term: “We trust our managers and employees and hence try to encumber them with as little bureaucracy as possible. We encourage our managers to launch initiatives, which in our industry, often require 5-10 years to generate payback. We are comfortable providing them with capital to purchase businesses that won’t immediately be accretive, but that have the potential to be long-term franchises for CSU” - Mark in 2011.

They understand true return on capital better than an average management team, and calculate their own adjusted net income and invested capital over time to reflect the fact that most intangible assets do not actually diminish in economic value.

So far as it doesn’t erode their competitive position, Mark has been extremely transparent about how he thinks, the challenges CSU faces, and how his mind changes over time.

CSU is an organization that relies on data to make decisions. You can’t manage what you don’t measure. If the data suggests that conventional wisdom is wrong, they have no problem stepping outside the box. They would rather succeed unconventionally than fail conventionally. At the bottom of one letter Mark quotes Jeffrey Pfeffer: “You can’t be normal and expect abnormal results”.

That last point is perhaps the most important, because I believe it’s the primary underlying reason for CSU’s abnormal success. There is no better display of that thinking than Mark’s comments on Director selection (2017 President’s Letter). It’s a lengthy thought, but trust me, it’s worth the read:

“Qualified and competent Directors are very rare, and not surprisingly, the track record of most boards is awful. According to the 2017 Hendrik Bessembinder study of approximately 26,000 stocks in the CRSP database, only 4% of the stocks generated all of the stock market's return in excess of one-month T-Bills during the last 90 years. The other 96% of the stocks generated, in aggregate, the T-bill rate over that period. This means that 4% of boards oversaw all the long-term wealth creation by markets during that period. Even more disturbing, the boards for over 50% of public companies saw their businesses generate negative returns during their entire existence as public companies

We recently received another challenge to our board practices. This time a significant shareholder (holding hundreds of thousands of Constellation’s shares) expressed concern about extended board tenures and a preference for "board refreshment". They proposed that we consider limiting board tenure to 10 years. I appreciated them consulting with us directly, rather than just putting it on the ballot as a shareholder proposal. I thought I'd respond to them as part of this letter so that all shareholders can see how we think about Director selection and tenure.

We believe that when you limit a competent Director’s term, you limit their opportunity to learn and hence to add value.

There was a 1994 peer-reviewed journal article about the role of deliberate practice in becoming an expert (Ericsson & Charness). The concept was popularised and extended by Malcolm Gladwell in his book "Outliers", as the 10,000 hour rule. I understand that you don't need 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to be able to fire a CEO who has his hand in the till or is abusing employees. I’ll refer to this as the “governance” role of Directors. However, I also think there's something to be said for Directors intently studying an industry and a company over a period of many years to acquire relevant expertise so that they can contribute more than just governing. I’ll refer to this as the “coaching” role of a Director.

In some instances, you are fortunate and can find Directors like Mark Miller and Jeff Bender who have 10,000 hours of relevant experience. They were master practitioners of the VMS craft long before they were appointed to the Constellation board. For most Directors, however, learning about VMS and Constellation’s particular approach to VMS, is a long journey. A couple of the outside Directors remarked how humbling it was to have these insiders on our board, because Jeff and Mark had so much context, experience and nuance to bring to most board discussions.

Our outside Directors spend about 30 hours in board meetings each year, and let’s assume preparation time doubles that. For an especially engaged Director, committees, special projects and extra-curricular Constellation-related activities might drive their time with us up to 200 hours per year. At 200 hours per year, and if you believe the 10,000 hour rule, then this especially engaged Director needs to put in 50 years on the job to offer deeply contextual expert level coaching.

Some prospective Directors don’t have the appetite or incentive to invest 10,000 hours to make the transition from a monitoring/governing role to a coaching/nurturing role. Most prospective Directors are simply too old to make that journey. Unfortunately, that means that the default role for most Directors is as a governor not a mentor. Some investors find that acceptable. I’d argue that governing is table stakes. Coaching and talent nurturing are the places where Directors can make a significant contribution and help a company become part of Bessembinder’s 4%.

Simple math suggests that if a Director is not from the industry or the company, then they have no hope of coaching and nurturing unless they start in the Director job when they are young. Ideally we'd like to get them in their 40’s or 50's and keep them for 30 or 40 years or until their health deteriorates. We certainly don’t want to kick them out after they’ve served for 10 years.

We’ve been searching for great Directors for years. We’ve gone on long campaigns to land individual candidates whom we admire. One observation from those frustrating pursuits is that a lot of high quality people don’t want to be Directors. They may be intrigued by the company and the managers and the business philosophy. Despite that, the “policing” responsibility is an unpleasant one, and the prospect of investing a huge amount of time to learn the business and win management’s trust and respect is daunting.

There are a number of reasons people serve on boards: the halo effect of being associated with a good company, compensation, curiosity, and a desire to give back. However, I can think of only two really compelling reasons why a high-quality candidate would want to serve on a board and commit hundreds of hours per year to the task: 1) it is a way to invest a significant portion of your net worth and be able to watch it closely, and 2) you can learn and apply those learnings to your own career and investments.

I have difficulty forecasting long-term growth in Constellation’s intrinsic value per share that exceeds 12% per annum. For many Directors who are adept capital allocators, that is insufficient to justify investing a significant portion of their net worth. For them, the first compelling reason doesn't apply.

Only a tiny number of CEO’s/Owners/Managers and some academics are going to want to study Constellation’s decentralised multiple small business unit model for application in their own careers. That suggests the second compelling reason creates even fewer candidates. The overlap in the Venn diagram between high quality Director candidates and those that have a compelling interest in serving as a Director is tiny. Making Director tenures shorter, or limiting candidates to a particular gender, race, or religion, just exacerbates this situation.

The current movement to limit Director tenure makes great sense if you think your investee company is poorly governed. However, if you think the governance is good, then limiting Director tenure hurts the company. It is analogous to firing a high-performance employee on their tenth anniversary.”

I can probably count on one hand how many managers I’d trust over Mark and his team to manage all my capital. Don’t get me wrong, these people are fallible. They make mistakes. But they also learn from them, and change their mind when it’s the appropriate thing to do. It’s hard not to come across as a blind Mark Leonard fanboy, but it’s damn near impossible to ignore the fact that he might be one of the greatest managers of our generation. Jamie said it best: “Walk my dog, babysit my kids, I don’t care - you have my full trust”

Valuation & Scenarios

VMS Engine

The 5 and 10 year historical organic revenue growth rates at CSU (ending 2019, to ignore the impact of COVID) were ~0.5% and ~1.5% respectively. In the base case, I assume 2.1% organic revenue growth over the next decade. There are three reasons that my forecast is higher than historical growth.

I believe that the switch from licenses to SaaS products has understated historical growth, and that this should normalize over the next decade.

Ignoring licenses, Maintenance revenue has grown much faster than Professional Services and Hardware, and as Maintenance becomes a bigger part of total revenue, the drag from these other categories will diminish (see Exhibit L).

Most importantly, as CSU pursues larger acquisitions at loftier valuations (higher EV/Sales), it’s likely that they acquire businesses with higher organic growth rates than many of the small VMS companies they’ve acquired in the past. For example, historical organic growth at Topicus (acquired in 2021) and TSS (acquired in 2013) have typically been higher than those at CSU - these were the two largest acquisitions in company history.

CSU can achieve this organic growth with very little incremental capital. Based on historical capital intensity, I estimate that incremental ROIC from organic growth is north of 35%.

M&A Machine

I start with the assumption that CSU can deploy 50% of CFO on VMS M&A through the forecast period. This is lower than the 10Y historical average but more-or-less in-line with last five years. Under this assumption, annual M&A exceeds $2.0 bln by 2030. To deploy this exponentially growing budget, CSU will have to pursue larger M&A. The underlying assumption in my forecast is that they can complete 1-2 large deals per year in the short-term (in-line with Mark’s objective), and 3-4 large deals per year by 2030. Even still, they will need to double the amount of small transactions they complete every year.

As I highlighted earlier, I believe CSU has a number of competitive advantages that have allowed them to decentralize M&A successfully. I don’t see any compelling reason that the company (ex. TOI) couldn’t execute 140 deals/year (up from ~70 in 2020 and ~85 in 2019). Nevertheless, deal size (even for small deals) is bound to increase significantly. Excluding TOI, I assume that average deal size grows by 2.5-3.0x. As deal size goes up, I expect that EV/Sales on acquisitions will also rise, which results in falling incremental ROIC.

Exhibit O shows that my forecast for EV/Sales versus average deal size is consistent with the historical relationship between these two variables, if not slightly conservative. By 2030, I estimate that incremental ROIC is somewhere in the mid-to-high teens.

VMS Margins

Despite receiving no scale benefits in many categories (like R&D and S&M), I suspect CSU will realize very modest EBITDA margin expansion over the next decade from leverage on professional services, G&A, and hardware - although much less than they’ve enjoyed historically. Operating margins should expand at a faster rate, and the reason is more nuanced. Customer relationships make up a significant portion of intangible assets, which CSU amortizes over ~12 years. In reality, the useful life of these “assets” is much longer. As year-over-year growth at CSU slows (proportional revenue growth from M&A falls), the net book value of these intangible assets will fall. This reduces run-rate amortization, and leads to EBIT margin expansion in excess of EBITDA margin expansion.

CSU 2.0

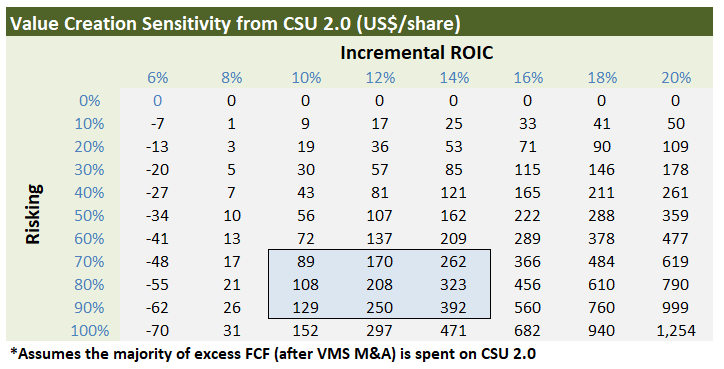

If CSU returned cash to shareholders, instead of pursuing new initiatives, that cash would would earn CSU’s cost of capital at 7.5-8.0% (assuming all investors can earn that return). In order for new initiatives to be accretive, CSU needs to earn in excess of that. The data table in Exhibit Q shows accretion under a range of scenarios. Mechanically, I assume that all free cash flow - after organic capex and M&A in the core VMS business - is deployed in new initiatives, and then risk that spending accordingly. For example, an 80% risking would mean that 80% of excess FCF is deployed in new initiatives.

In the base case, I’ve settled on an 80% risking at a 12.5% incremental ROIC, which adds $235/share to my estimate of fair value. I think it’s incredibly likely that CSU can find some new business to deploy significant free cash flow into, particularly if they also lower the hurdle rate for new investments. I pulled ROIC base rates from 1996-2018 for a group of potentially relevant businesses and set CSU 2.0’s ROIC to be slightly below the 10-year average (Exhibit R). It seems unlikely that CSU will outright fail, but I’m also hesitant to believe that anything they touch will turn to gold. This seemed like the prudent place to start, particularly if CSU is going to deploy US$10 bln over the next decade. Alternatively, I could have risked new initiatives at 30%, and instead used an incremental ROIC closer to what CSU earns today to arrive at a similar level of accretion.

Balance Sheet

In the base case, I assume that terminal ND/EBITDA approaches 1.0x, which would imply an interest coverage ratio of 14x. As the business grows and becomes more diverse, this seems inevitable, despite Mark’s historical reluctance to utilize debt. I suspect he’ll ultimately cave in, just as he accepted that CSU will have to lower hurdle rates to pursue large M&A and new initiatives. Exhibit S shows historical and forecast leverage metrics and sources/uses of cash. This change in capital structure increases my estimate of fair value by 12% versus a scenario where ND/EBITDA stays at 0.0x.

TSS Minority Interest

Starting in 2021, a significant portion of CSU’s consolidated cash flows will come from TOI (TSS spin-out). The book value of minority interest is bound to be <$500 mln, but this doesn’t properly reflect the economic interest of TOI shareholders. After all, CSU trades at more than 20x book value. The base case in my TOI model suggests a fair value of equity in the US$7.5 bln range. On a fully diluted basis, CSU will continue to own 30% of the float, so the true minority interest that I use when calculating the fair value of CSU is ~US$5.0 bln.

Tying it all together/Outputs

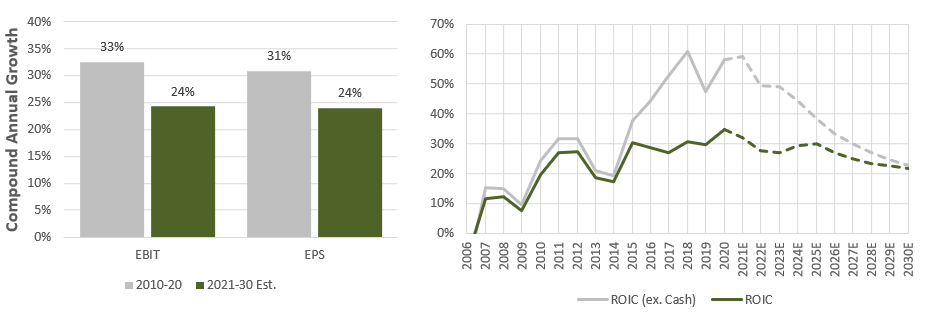

Even with new initiatives, the base case assumptions show that EBIT and EPS growth falls in the forecast period relative to the most recent decade (Exhibit R). ROIC ex. cash falls meaningfully as significant capital gets spent at much lower incremental ROIC. Nevertheless, CSU continues to earn a multiple of their cost of capital well into the future.

The DCF model shows that fair value in the base case is ~US$1,750/share (C$2,200), which is 30% higher than the current share price. A snapshot of the model is shown below. Another way to think about this is that a long-term investor could expect a 10% annual return in the base case.

It’s helpful to think about the base case as the sum of three components: the existing business, value from VMS acquisitions, and value from CSU 2.0. Exhibit V splits this out. To value the base business, I took all VMS M&A to zero after 2021, and ignored the CSU 2.0 initiatives. I assume organic growth increases slightly to 2.5% from 2.0% because more human capital will be spent solving those problems. What I find particularly interesting is that the market doesn’t appear to be giving CSU any value for new initiatives, and is risking my VMS M&A assumptions by 40%. The implication is that the market isn’t pricing in large VMS M&A.

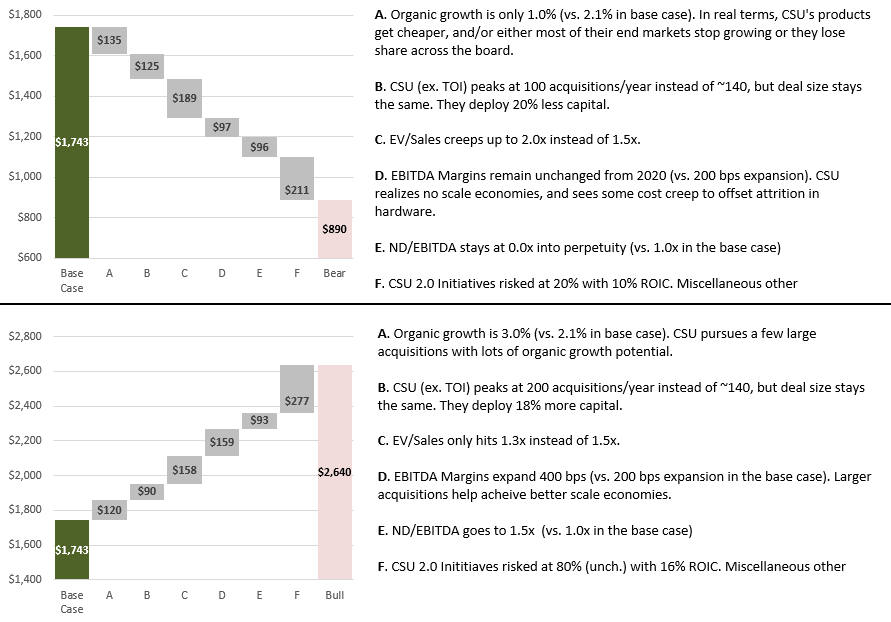

The base case isn’t particularly useful without understanding the range of outcomes. The bear and bull scenarios in Exhibit W are meant to represent something close to the 10th and 90th percentile outcomes.

In Exhibit W, I plot these scenarios vs. the current price to help visualize risk. It’s clear that I believe CSU is mispriced and that risk is significantly skewed to the upside.

I don’t believe that I have a meaningfully differentiated view about the value of the base business. The market understands this well. What I think the market misses is that CSU is really good at M&A, and has a number of competitive advantages that should allow them to simultaneously scale small M&A at extraordinarily high ROIC and also execute on large deals at an ROIC much higher than their cost of capital. I’m also confident that the market is giving CSU zero value for CSU 2.0. I understand why the share price wouldn’t reflect this, but I disagree with the sentiment. Mark and the team have exhibited a pattern of behavior that suggests they will be excellent capital allocators wherever they set their sights. It’s easy to imagine Mark and the gang setting up a private equity business and deploying capital at attractive ROIC, even if that ROIC isn’t the 30%+ that CSU shareholder have been used to. He deserves the benefit of the doubt. My analysis, particularly the illustration in Exhibit V, makes me comfortable taking the over on current market expectations.

What would the 10th (wo)man say?

As CSU scales, particularly into new initiatives, it might become difficult to hold bureaucracy at bay. Bureaucracy creep could erode the company’s ability to maintain a truly decentralized structure, which could lead to lower organic growth and lower returns on M&A.

The uncertainty surrounding new initiatives also makes it difficult to assess future returns and capital deployment opportunities. If CSU enters the wrong industry, or poorly executes a growth strategy, the new initiative could end up being dilutive to shareholders. This seems unlikely, but the probability isn’t 0%.

In one unlikely scenario, CSU could also create an asset management business and earn an attractive fee on AUM, which isn’t unprecedented. Even if the IRR in those funds was significantly less than what CSU earns today, it could still be a profitable new initiative. Thoma Bravo just raised $23 bln of equity commitments for a new round of funds, which could generate upwards of $1.0 bln per year in fee-based income. CSU could invest capital alongside fund investors (much like Brookfield), and target much larger deals. This seems unlikely, but I’ve seen multiple examples of this happening in other industries (like real estate and infrastructure). My bull case scenario would be much higher if they did this successfully.

Got here via MBI Deepdives. This is insanely good.

Hello there,

Huge Respect for your work!

New here. No readers Yet.

But the work has waited long to be spoken.

Its truths have roots older than this platform.

My Sub-stack Purpose

To seed, build, and nurture timeless, intangible human capitals — such as resilience, trust, evolution, fulfilment, quality, peace, patience, discipline, relationships and conviction — in order to elevate human judgment, deepen relationships, and restore sacred trusteeship and stewardship of long-term firm value across generations.

A refreshing poetic take on our business world and capitalism.

A reflection on why today’s capital architectures—PE, VC, Hedge funds, SPAC, Alt funds, Rollups—mostly fail to build and nuture what time can trust.

Built to Be Left.

A quiet anatomy of extraction, abandonment, and the collapse of stewardship.

"Principal-Agent Risk is not a flaw in the system.

It is the system’s operating principle”

Experience first. Return if it speaks to you.

- The Silent Treasury

https://tinyurl.com/48m97w5e