Reviewing the Initial Thesis/Base Case

It has been nearly two years since my original CSU deep-dive, and I feel due for a refresh. I think a good place to start would be a post-mortem on the original thesis/base case.

The initial thesis:

“Constellation’s existing VMS businesses generate a predictable stream of cash flows, and benefit from the diversity of serving dozens (if not hundreds) of verticals across multiple geographies, and hundreds of thousands of customers. Their mission critical software is a need-to-have service, a small share of the customer wallet, and not easily replaced. Most VMS incumbents benefit from not-so-obvious barriers to entry, and a weak competitive playing field. This all leads to sticky customers and low churn. This diversity and low churn limits downside risk for the existing business, which is an attractive feature for investors, but also well understood by the market.

In my opinion, the market primarily misunderstands two things. First, CSU has a world-class management team and a number of competitive advantages that allow them to scale VMS acquisitions at attractive incremental ROIC. In particular, they have perfected a decentralized M&A process, and have a reputation as being great perpetual owners of VMS businesses. I don’t think they get full credit for this. In particular, I think the market is discounting large VMS M&A. Second, my analysis suggests that CSU receives almost no value for new initiatives (CSU 2.0), which means that the market expects the company to distribute a significant portion of FCF to shareholders instead of finding new accretive ways to deploy it. I wholeheartedly disagree.

In addition, CSU could easily increase net leverage given the stability and competitive position of the base business. Pulling this lever could result in significant distributions to equity holders and/or fund new initiatives without really increasing the risk profile of the business. This tends to be a corporate action that rarely gets properly reflected in valuation, even if it’s ultimately inevitable.

This is an extremely high-quality business, with a proven core strategy and world-class leadership team and culture. While some uncertainty exists around future growth initiatives, I believe the current price represents a substantial discount to fair value (25%), and more then compensates for this risk.”

Some things haven’t changed: I still believe that CSU owns a remarkable portfolio of businesses and is led by a world-class management team; I still think that they can redeploy FCF at attractive – albeit diminishing – returns via VMS acquisitions; the untapped balance sheet has value to equity holders and we’re starting to see that lever be pulled; and finally, I think it’s clear that Mark is still actively looking for CSU 2.0 and that has some value. Two years ago, I thought the market misunderstood some of these things like the value CSU could recognize from large VMS M&A, the upside from CSU 2.0, or the benefit from starting to use more leverage. Today, I’m not so sure. CSU’s share price is up ~30% since my initial deep dive, and whatever differentiated view I held back then no longer seems to apply – but let’s put a pin in this until the end.

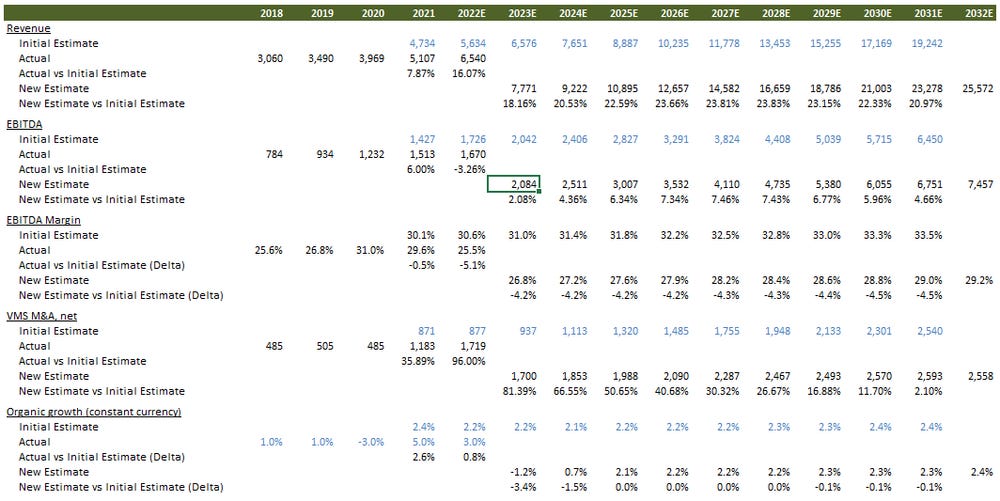

As for my estimates, Exhibit A shows my initial base case vs actuals in 2021 and 2022 (using ~consensus for 4Q22). For starters, CSU deployed way more capital on net VMS M&A than I estimated – cumulatively 60% more over the last two years, and on average they paid roughly what I would have expected on an EV/Sales basis. Constant currency organic revenue growth was also modestly higher than my base case. As such, revenue is trending significantly higher than my base case. Those were the positive surprises. On the negative side, while EBITDA margins were more-or-less in-line with my 2021 estimate, EBITDA margins are likely to be a whopping ~5% lower than my 2022 estimate (25.3% vs 30.6%). Margins haven’t been that low since 2015! The net impact is that CSU deployed significantly more capital than I expected but ended up generating slightly less EBITDA than I expected. There was also a change to U.S. tax law in 2022 with respect to R&D, which used to be fully deductible as incurred but is now capitalized and amortized. Immediately following that change, cash taxes go up, but the tax benefit eventually gets realized and this change doesn’t have a huge impact on total FCF over time. With a few other minimal variances, FCF excluding growth capex/M&A is going to end up being about 14% less than my initial base case for 2022.

Ignoring the tax change, the biggest negative surprise vs my initial base case was EBITDA margins (the R&D tax stuff should roughly normalize in time), so it’s worth starting the detailed post-mortem there.

EBITDA Margins

Exhibit B shows historical margins – annually from 2005-2017, and quarterly from then onward. EBITDA margins were 27.5% in the last quarter prior to COVID. They peaked at 33.0% in 3Q20 and were 31.9% in 4Q20 (after which I published the initial deep dive). More than half of that margin expansion was the direct result of less travel to trade shows and to see customers/targets. That was obviously a transitory margin uplift, and I expected that travel spend would resume post-COVID, which is why I modelled margin compression into 2021/2022 from 4Q20 levels. Since then, travel spend has nearly recovered to pre-COVID levels, which explains some of the margin decline through 3Q22.

But margins are down much more than I expected. One culprit is Altera (the entity acquired from AllScripts), which officially became part of CSU in 2Q22. Altera’s EBITDA margins are something like 6-7% lower than core CSU and is contributing to ~1.0% of that margin compression. In the near-term, that’s likely to continue being a drag. That still leaves me with a 4.0% delta between the base case and actual 2022 margins. About three quarters of that remaining delta can be attributable to “Other, net” coming in much higher than I expected.

“Other, net” includes stuff like advertising and promotion, recruitment and training, contingent consideration revaluation, and government assistance. In aggregate, these items fell from roughly 2.0% of revenue prior to COVID to literally 0% in 2Q20, and were just 0.3% in 4Q20. There were a few reasons for this reduction in spend: hiring fell off a cliff and recruitment/training expenses followed suit; advertising spend fell by nearly 50%; government assistance provided for an obviously transient cash inflow; and contingent consideration revaluation (which is technically non-cash in the period recorded, but ultimately represents a cash outflow) fell to nearly nada. Any reasonable observer would have expected all of this to normalize as we come out of COVID. What did I assume? Not that. There are no two ways about this, I made an easily avoidable mistake! So, for starters, it looks like my initial EBITDA margin estimates were too high. It doesn’t bother me to get things wrong within reason but making silly mistakes like this is on par with getting my fingernails removed with pliers. My bad.

But “Other, net” didn’t just normalize over the last few quarters – it skyrocketed. Exhibit C shows that these expenses were proportionally almost 2x higher in 3Q22 than they were pre-COVID! Now that I’m critically evaluating these cost items (not extrapolating like a neanderthal), I think it’s clear that some of this spend should normalize (but the other way). For example, one third of the “Other, net” expense in 3Q22 was contingent consideration revaluation. In dollar terms, contingent consideration revaluation expense was 11x higher this quarter than the same period last year, and 6.6x and 3.7x higher this quarter than the full year of 2020 and 2019 respectively. This expense is tied to earn-out payments from acquired businesses – when those businesses are outperforming initial expectations CSU pays the seller more money, and vice versa. This expense item represents CSU’s expectation of future performance within the earn-out period, and clearly their expectations for future performance were too pessimistic during the depths of COVID and are being rightsized now. In my view, this is transient. Even if it wasn’t, higher contingent consideration revaluation expense is implicitly an indicator that acquired businesses are exceeding CSU’s expectations (higher organic growth, better margins). Similarly, some of the recent increase in advertising, recruitment, and training seems to be a function of catching up from a period of underinvestment – this too should normalize lower.

The other expense line items are more-or-less tracking where I’d expect for a given level of revenue. The only exception is direct staff expenses which is likely attributable to wage inflation in the tech space outpacing organic growth/price increases. Those direct staff expenses have some seasonality but have generally trended higher as a percentage of revenue over the last 4-6 quarters. In fact, during the first three quarters of 2022, seasonally adjusted staff expenses as a % of revenue were slightly higher than at almost any point in the last decade. At the 2022 AGM one CSU executive commented that “it’s become harder to retain staff, especially during this pandemic… because work has become more a computer and a paycheck… Amazon can hire somebody in any one of our operating units in any geography, and it’s kind of hard to compete with some of these companies like Amazon and Netflix and LinkedIn”. I’d bet that this cools down in 2023 given some of the pressure and layoffs we’re seeing in the broader tech space. I also suspect that price increases at BUs lag wage inflation (you have those price increase conversations with customers after you start to feel input cost inflation), which might explain modest margin compression in the near-term, but should ultimately sort itself out. And the beautiful thing about CSU’s products and services is that they are such a small percentage of the customer wallet that it’s easy enough to hike prices without hurting customers.

I expect to see slightly higher EBITDA margins over the next 1-2 years off the 3Q22 numbers as some of those “Other, net” items normalize, and wage pressure subsides/software prices catch up. Beyond that, I still believe that there is some modest potential for margin expansion in a handful of cost centers (driven in part by revenue mix shift away from hardware). Even still, I need to reduce my EBITDA margin estimates across the board because of the errors I’ve already highlighted and the drag from Altera. I’ll amalgamate all my revisions at the end of this piece, but the revisions are small enough and run-rate margins are still in the high-20% range.

M&A

A quick recap of the M&A story is in order before diving into what’s changed in the last two years.

For the first 20 years of their existence, CSU was small enough that they could easily deploy all their FCF on new acquisitions – there were enough small VMS deals that met their hurdle rates to satiate the M&A beast. Starting around 2015, CSU began to generate more FCF dollars then they could redeploy on small VMS M&A, despite the absolute dollars being deployed on acquisitions growing an astounding 9x from 2005. For five years, CSU accrued cash and ultimately paid out a large special dividend. Mark was hesitant to lower hurdle rates as a mechanism to deploy more capital after observing that “hurdle rates are magnetic” (see my initial deep dive for the full reference). Nevertheless, they succumbed in 2019, and lowered the hurdle rate for large acquisitions while keeping hurdle rates for small VMS businesses unchanged. A large transaction was defined as requiring an equity check greater than US$100mn (roughly 15-20x the historical average transaction size). The actual hurdle rates seem to be a well-guarded secret as I’ve never seen any reference to specific figures, but I’d hazard a guess that the hurdle for small VMS M&A is something like 20%, and the hurdle for large VMS M&A is probably mid-teens (Mark once mentioned that “bad” investments are “ones that generate double-digit rates of return, but just not their hurdle rate”).

Within a year of lowering the hurdle rate for large transactions CSU completed the Topicus acquisition (€217mn EV) and then subsequently spun-out TOI. My best guess is that Topicus might generate some low-teens unlevered IRR. With the addition of non-recourse leverage, I think CSU is probably getting a levered IRR somewhere in the mid-teens range.

When I initially published the CSU deep-dive I thought that CSU might complete 1-2 large VMS deals per year as they experiment with bigger transactions, where the aggregate spend on large VMS M&A would be ~$350mn/year. In the fullness of time, I thought maybe they could ramp up to $1.0bn/year in large VMS M&A. But then in 2021 they completed three large VMS deals (in addition to Topicus) for an aggregate gross purchase price of $370mn. That took total spend on large VMS M&A to almost $650mn (including Topicus), which was almost double my expectation and helped drive total acquisition spend of more than 2x what they completed in 2020.

In early 2022, Harris (a CSU OG) announced that they would be acquiring the electronic health records business from Allscripts for ~$700mn (now called Altera). To put that into perspective, that’s a bigger single ticket than all the combined M&A completed by CSU in 2020. CSU then closed on three other deals throughout the rest of the year – each just shy of $100mn – taking the total spend on large VMS businesses to nearly $1.0bn… almost 3x my base case estimate. Combined with 130 small VMS acquisitions (according to RBC), total net M&A is set to end the year at roughly $1.7bn!

That brings us to 2023, where two weeks into the year we already know that the WideOrbit acquisition is set to close for almost $500mn (the actual cash outlay is only $275mn). At this rate, it wouldn’t shock me at all if CSU once again showed a sequential annual increase in total M&A for 2023.

To put all this in perspective, Exhibit D shows historical M&A in absolute dollars, acquisitions/year, average acquisition size, and net M&A as a percentage of CFO. Note that 2022 was the first year since 2013 that CSU deployed more than 100% of their CFO on new acquisitions. In my mind, they’ve dispelled any concerns about their ability to ramp up acquisition spending.

If we measure M&A success as the product of A) capital deployed, and B) return on that capital, and we’ve already addressed part A, then the next obvious question is what have returns done as CSU leaned into large VMS M&A?

Assuming you’ve read my previous CSU piece, you’ll recall that I ran a regression of EV/Sales vs average deal size from 2008-2020, and that regression gave us some framework for thinking about returns as deal size scaled (this was the best proxy I was able to get from publicly available information). In Exhibit E, I show the initial regression with the additions of 2021 and 2022 to the series. The 2022 data requires some estimating, but the margin of error should be small considering we have official data for 75% of the year and enough piecemeal data for 4Q22 to make a good guess. At first blush, I find it encouraging that both 2021 and 2022 acquisition multiples came in close enough to the line of best fit – this is what I expected to see as average deal size increased with large VMS M&A.

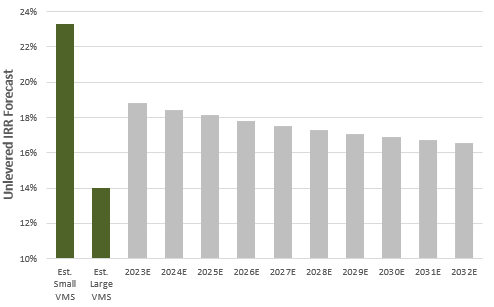

The working assumption here is that EV/Sales is a reasonably consistent proxy for returns given the generally homogenous characteristics of acquired businesses – EBITDA margins, organic growth profile, and capital requirements all tend to be similar to the existing CSU portfolio. At 1.0x EV/Sales, I previously estimated that unlevered IRRs were close to 25%. At 2.0x EV/Sales, I previously estimated that unlevered IRRs were somewhere around 15% - if not a tad less. While I generally still believe that to be the case for most of the M&A CSU is completing, the relationship between EV/Sales and unlevered IRRs doesn’t always hold for large VMS acquisitions where the targets can look very different from the average VMS business in their portfolio. There are two large acquisitions we can look to as examples.

The first is the carve out deal with Allscripts in early-2022 for a little more than $700mn – now called Altera. CSU paid something like 0.8-0.9x EV/Sales for that business, but Altera is generating EBITDA margins of just 15-16% (that’s what the first full quarter under CSU ownership shows). As a result, EV/EBITDA is more like 5.5-6.0x, whereas historically it looks like CSU acquisitions seem to come in around 3.0-4.0x EV/EBITDA. Altera has also posted mid-to-high single digit negative organic growth over the last few years (this may very well continue) whereas the CSU portfolio generates low-single-digit positive organic growth. If I assume that organic growth is -3% into perpetuity and margins compress modestly over time, I get an unlevered IRR of just 12% - that’s substantially different from the 25%+ implied by my historical EV/Sales calculations. But CSU took out some non-recourse debt at Altera, and assuming this debt charges 7% and gets repaid over a decade, my levered IRR is more like 16% (Lawrence Cunningham said that using leverage was the only way to get to their hurdle rate, fwiw). For a deal of this size, I would have expected EV/Sales of >2x and levered returns roughly in this range. So even though my historical short-cut for thinking about returns didn’t seem valid here, the underlying return when I modelled the deal out individually was more-or-less in-line with what I would expect. I’d consider this a win, and it’s one data point to validate my thesis that CSU can successfully deploy large amounts of capital in large VMS M&A at satisfactory returns. It’s also important to recognize that the operating group manager now overseeing Altera expressed the view that CSU could “service that customer base” better than Allscripts. He was careful to say that this was just his opinion, and I’m 99% sure they didn’t underwrite that scenario… but if that turns out to be true, and they can arrest the negative organic growth, returns would end up being higher than what I’ve laid out above.

I also found it really interesting that CSU had been building a relationship with Allscripts “for probably a decade”, “and then it just came to the right time, right opportunity where there was actually something we could do”. Think about that. CSU had been nurturing a relationship for a decade! Then think about how many other relationships they’ve been nurturing, and what else might fall in their lap because of lowering hurdle rates on large VMS acquisitions, particularly if we head into a recession.

The second large deal is WideOrbit, which I touched on in the Lumine deep-dive (here). By my estimate, WideOrbit is being acquired for 2.8x EV/Sales or ~10.0x EV/EBITDA. That’s substantially higher than the regression model would suggest for a deal of this size, and the implied unlevered IRR using my old framework would be a measly 7%. But like Altera, WideOrbit has some idiosyncrasies relative to the aggregate CSU portfolio. Most obvious is that organic growth at WideOrbit has come in >2x higher than CSU over the last two years. Unsurprisingly, organic growth that doesn’t require a ton of incremental capital has almost a 1:1 relationship to IRRs – a 1% increase in organic growth is ~ equivalent to a 1% increase in IRR. As I explained in the Lumine piece, I think WideOrbit has two levers they can pull to drive 10%+ organic growth for another 5-10 years (marketplace and pricing power). If that plays out, I can easily see a path to some low-teens unlevered IRR. Layer in some additional debt that’s going to get taken out within Lumine, and the levered IRR could end up being 15-20%.

To summarize, over the last two years I think CSU has exceeded my expectations for capital deployed and appears to be generating returns on that capital that are consistent with what I expected, even if that EV/Sales framework isn’t always relevant. To the extent that there were concerns about their ability to profitably execute large VMS acquisitions, I think the recent track record lays some of that to rest. As a shareholder, I’m also happy to see that CSU continues to prioritize ROIC over anything else – they are just as happy buying a shrinking business (Altera) as a business with high growth prospects (WideOrbit) so long as hurdle rates get met.

Some closing comments for the M&A section.

First, I expect that a higher interest rate environment makes CSU more competitive in the large VMS arena so long as rates are persistently high. Competing buyers that previously would have relied on more leverage to get deals done are now less competitive with a higher cost of capital, and sellers will eventually adjust their price expectations lower (at least in theory).

Second, I also believe that CSU’s M&A engine is countercyclical. In a recessionary environment, CSU should continue to generate a consistent and predictable stream of FCF, while that won’t necessarily be the case for other buyers. Corporates might also be more willing to entertain carveouts of non-core VMS businesses in a recessionary environment, and CSU is an obvious home for transactions like this (recall Altera was a carve-out deal, and they’ve done plenty of these).

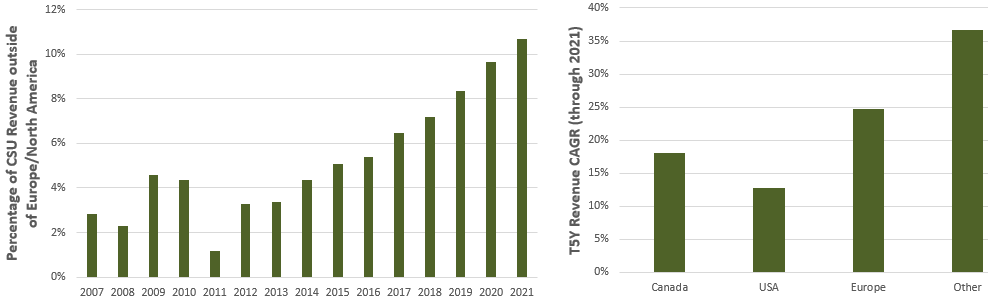

Finally, I’m increasingly confident that CSU will be able to close proportionally more deals outside of North America and Europe than they are closing today. Exhibit F shows the proportionate of revenue coming from outside North America and Europe, and the trend is encouraging. Various CSU executives have acknowledged that it’s hard to connect with local sellers without a presence in that country, which obviously makes it hard to close deals in new geographies. But as they develop a local presence, a snowball effect takes hold as they build relationships with other VMS owners and train operators from acquired businesses to adopt CSU best practices for M&A. Mark has already commented on how expansion into South America at two of the operating groups happened quietly but appears successful so far. In recent years we’ve also seen investments in historically off-the-beaten-path places like South Africa, Singapore, Pakistan, and Japan (the latter of which happens to be a “personal pet project” for Mark). Ten years from now, if CSU can continue to penetrate South America, Africa, and Asia, then I see no reason they won’t be completing 200 small VMS deals/year. All the data and commentary I’ve assessed to-date tells me CSU is well on the way to making this happen, which likely explains how they’ve continued to ramp up total acquisitions/year to 134 in 2022, up from just ~50 in 2017.

All told, the M&A engine has exceeded my expectations and I’m more optimistic about CSU’s ability to deploy an ever-growing pool of FCF without reducing hurdle rates any time soon. I’ll have to revise up my initial base case estimates as a result.

CSU 2.0

Recall that two years ago in Mark’s last letter to shareholders he says:

“In parallel with our established and growing small and mid-sized VMS practise and our nascent large VMS practise, we are trying to develop a new circle of competence. We are seeking attractive returns, a sustainable advantage, and the ability to deploy large amounts of capital outside of VMS. That will require highly contrarian thinking and is likely to be uncomfortable in the early going. Hopefully, we have built enough credibility to warrant your patience as we explore new and under-appreciated sectors.”

One year later at the 2021 AGM, Mark commented again:

“I also looked at a couple of opportunities outside of vertical market software, one of which has gone away but was a big dollar potential deployment outside of vertical market software and the other one of which is a sort of nascent industry opportunity that I think we have a unique skill set to bring to the party and some good unfavorable economics, favorable to us and favorable to much of the rest of the world. And I'm excited about it, but it's a very long-term prospect. And will not be an early obvious win, would impact – look very contrarian. And -- but it has this -- it has a huge, embedded option. So that's what I've been spending time on.”

In the same AGM he goes on to say:

“So, it's not like people bring us opportunities. We go looking for opportunities. And where do we go look, we go look where other people aren't looking. And so, bring me your sick, your tired, your ill and we'll have a look. You've got to be contrarian to get superior results. And then you've got to have a process of protecting whatever advantage you have once you've discovered, unearthed and shown the world that there are superior results to be had. So, what we're looking for is a needle in a haystack. It's – the likelihood of success is near 0.”

At the 2022 AGM he echoes a similar sentiment:

“I mean the uncertainty of non-VMS is that there are hundreds of thousands of Harvard and Stanford and MIT and God knows what all else, MBAs, hustling around, trying to find places where you can generate alpha. And so the likelihood of us being able to find another place to generate high rates of return on significant amounts of capital in a predictable way for decades is bloody low. And so I would tell you, don't count on it, but we're working on it.”

But then he follows it up later in the 2022 AGM with this:

“I took a hard look at a thermal oil situation. I was looking at close to $1 billion investment, and it was tax advantaged. So it was clever structure. It was at a time when the sector could not get financing. And unfortunately, the oil prices ran away on me. So I was trying to be opportunistic in a sector that was incredibly beat up. So that is an example.”

Two years ago, I thought that CSU would struggle to deploy most of their FCF back into VMS M&A, even as they pursued larger acquisitions. If there was going to be FCF left over, I felt reasonably confident that Mark would succeed at finding some other place to deploy that cash at a return greater than investors might otherwise generate if that excess FCF was returned to them. I dubbed that yet-unknown venture CSU 2.0.

Here we are two years later, and despite what appears to be an honest effort on Mark’s part (as evidenced by some of the commentary above), no CSU 2.0 has emerged. So, the bad news is that Mark has actively looked for CSU 2.0, got as far as identifying opportunities, and then those opportunities slipped away from him. Two years into the hunt and we’re empty-handed. Maybe Mark’s right that the “likelihood of success is near 0”. The good news is that CSU hasn’t needed to rely on CSU 2.0 just yet. They’ve deployed more than 100% of their CFO on new VMS M&A. That’s a great outcome, and Mark has said plenty of times that if CSU can get their fill with VMS M&A then they’d never need to explore other opportunities.

Despite VMS M&A outperforming my short-term expectations and soaking up all available capital, it’s inevitable that at some point the reinvestment rate into CSU’s core competency will fall well below 100%. With near certainty I can say that all of CSUs managers and directors are keenly aware of this, and so I suspect Mark will continue the hunt.

Where Mark’s commentary guides investors to peg the probability of success for CSU 2.0 at something close to zero, I’m actually much more optimistic. For starters, think about how many intelligent curious people are indirectly contributing to the search. Andrew Pastor joined the board recently and is a partner at EdgePoint – his day job is literally to suss out good investment ideas. There are more than a dozen other board members, a few other operating group executives, and hundreds of portfolio managers and BU managers at CSU who we can think about like a massive idea-generation network. It’s also worth pointing out that the preceding two years were unusual in that interest rates were extremely low, valuations across the board were extremely high, and there seems to be an abundance of capital competing for deployment. Hunting for CSU 2.0 in that environment must be infuriating. But the party already seems to be winding down, and one day capital will once again be scarce. When that happens, I suspect the opportunity set improves. Finally, Mark has a history of downplaying the probability of success at CSU and is the least promotional executive I can think of. Andrew Pastor wrote an entertaining piece about his experience with this (which you can find here), where Mark basically tried to dissuade Andrew’s firm from looking at CSU. I can understand why he does this too – if his employee shareholders (who are often required to purchase CSU stock in the open market) acquire expensive shares, that could ultimately be a drag on morale. So why wouldn’t you talk down your prospects?

All told, I’m a tad disappointed that nothing has come to fruition just yet but can also understand why it hasn’t. I have no idea when, but still peg the probability of CSU eventually finding new areas for capital deployment well north of 50%... it might just be later than I initially thought, but I’m fine being patient on that front.

Spin Outs - A Cornered Resource?

There are other reasons why CSU would spin out public companies in addition to combating bureaucracy creep and better aligning incentives (both of which I touched on with Lumine). Mark Miller spoke about this at the 2022 AGM:

“Tell you what, Howard, why don't I interject with a setting of the scene for why we do a lot of these spinouts. Usually, it's an opportunity to buy a very significant company, one that we couldn't justify if we were buying it for cash. And so what we're doing is we're putting in some cash and we're using the shares of the spin-off as partial payment. That creates alignment with the large company shareholders and give them the upside on those shares once we spin the business out. So they get a blended set of proceeds. They are clearly more aligned than they would have been if they sold to us for cash, and we can be more competitive with private equity to do this a lot, where it isn't that they're going to spin out and make it public, but they're going to sell the whole thing hopefully have some huge multiple to the next buyer and the group that has sold to them, a portion of their business will have a the second pay day. And so our second pay day that the company goes public, and they can continue to be shareholders and the companies that they founded and built and they can feel a sense of pride that it's now an independent company and that is going to remain public and not subject to takeover as long as Constellation is a significant shareholder. So that's the theme that we're trying to set. That's the dream that we have for these things. We hope it will allow us to buy very large companies that we wouldn't otherwise get the chance to buy.”

With both TOI and Lumine, the spin-out transaction happened in conjunction with a large deal, where the selling shareholders of that large private VMS business took part of their payment in stock of the spun-out public entity. It’s difficult to explain the advantage of doing this without an illustration, so I refer you to Exhibit G.

Most of what I’ve shown in Exhibit G we have hard data on like the total consideration paid for WideOrbit, the purchase price allocation, and the fully diluted share counts. We have a pretty good idea what initial EBITDA from WideOrbit should be based on reported data from the last three years. And then we make an educated guess at where Lumine shares will trade once it’s spun out (I shaved a dollar off my Lumine base case estimate).

In this instance, CSU acquired 55% of the WideOrbit business, while the WideOrbit sellers retained 45% of their equity valued at $6.34 per Lumine share. For the sake of this example let’s assume that Lumine trades at $12.00/share (roughly where I actually think fair value is for public markets). Now, instead of the WideOrbit shareholders receiving a total consideration of $497mn, the total value they’ve realized is $695mn – a whopping 40% higher. So, CSU paid 11.0x EV/EBITDA for their share of this business, but WideOrbit will realize 15.5x. If we assume CSU was targeting a levered IRR of 15.0% at the $497mn purchase price, a competing bidder would have had to accept a 10.1% levered IRR if they were underwriting identical assumptions and wanted to present an equally attractive bid. I don’t expect there are a lot of competing bidders that can stack up to a deal structured like this.

By allowing sellers to roll a portion of their equity into a new public vehicle, they are essentially letting them bridge the public vs. private market valuation chasm to realize more total value on the sale. Of course, this has the added benefit of ensuring sellers stay engaged post-close.

As I write this, I can’t help but feel like I’ve stumbled across a new CSU competitive advantage specifically in the large VMS arena. I’d very loosely call this a cornered resource… where the resource is the largest collection of small VMS businesses in the world that can roll up under various little distinct umbrellas and easily attach themselves to large new VMS businesses that fall under the same umbrella. What other company on the planet can do that? Who has 30 global transportation software businesses ready to get spun out alongside a $400mn transportation software acquisition? Or a similar collection of [pick literally any niche industry] businesses? If I recall correctly, CSU has >1,000 BUs today, which really puts in perspective how many of these they can probably do (Lumine is just 2 dozen BUs). That resource is finite, but the pool from which CSU can mix and match to create new organizations gets replenished every year as they acquire the next 100+ small VMS companies. In any event, you take this “cornered resource”, combine it with the creative deal terms we’ve seen with TOI/Lumine, layer in the added reputational benefits that attract sellers to the CSU organization in the first place, and by golly you’ve got yourself a lean, mean, fightin’ machine!

At the 2022 AGM Mark was asked if he’d studied other HPCs that used spinouts to sustain performance over time. He responded with:

“Certainly. Henry Singleton used them several times. John McCain used them several times. Forina use them frequently. They are a tool. There’s no doubt that they have contributed to spectacular performance.”

Admittedly, I haven’t studied some of the examples used above in any real detail, but if my math from Exhibit G is any indication, I think there is something special here. In any event, the signaling is bright as day: EXPECT MORE SPINOUT TRANSACTIONS. Volaris has already created a handful of other brands that are a collection of VMS businesses in the same vertical like Modaxo (transportation) and Vencora (financial services). These strike me as prime candidates for future spin out transactions.

In closing, this strategy is sure to help CSU deploy more capital at attractive returns than I initially expected. Another reason to revise my original base case higher.

Leverage

Another leg in my initial thesis was that CSU would ultimately use more leverage, which would add value to equity holders without materially changing the risk profile of the business. Exhibit H shows a breakdown of debt by type alongside EBITDA. The first time CSU really utilized debt was when they temporarily tapped their credit facility to acquire TSS, after which they issued the 2040 debentures and some non-recourse debt at the subsidiary to repay the facility. They issued more non-recourse debt at the subsidiary level after they acquired Acceo in 2018 (another large acquisition). Since publishing my first CSU deep dive, outstanding debt balances have more than tripled as they’ve continued to lean into non-recourse debt to fund large acquisitions (TOMIA, Altera, Topicus, and soon-to-be WideOrbit). ND/EBITDA exiting 2022 is still a measly 0.4x, but it’s higher than at any point since the TSS acquisition was funded.

“In ring-fenced acquisitions, we'll obviously use leverage. And we use it as a competitive tool if our competitors for those acquisitions are using leverage tied to that particular acquisition. And we ought to be competitive. We have no choice, but to do the same… We want to make sure that at Constellation, we have access to enough resources that if any of our ring-fenced companies get into trouble, we'll be able to recapitalize them. So the idea is to have a very well-financed core business and then perhaps some leveraged subsidiaries, as the opportunity pop up, that we can basically be a backstop for. That's how we think about debt.” – Mark Leonard, 2020 AGM

I still believe that CSU will utilize more leverage in the future, but that most of this leverage will be ring-fenced at subsidiaries and have no recourse to the parent. The underlying reason for doing this is to be more competitive for large VMS acquisitions while striving to hit levered IRR hurdles. If it helps CSU deploy more capital at equity returns in the mid-to-high teens, that’s fantastic.

Valuation

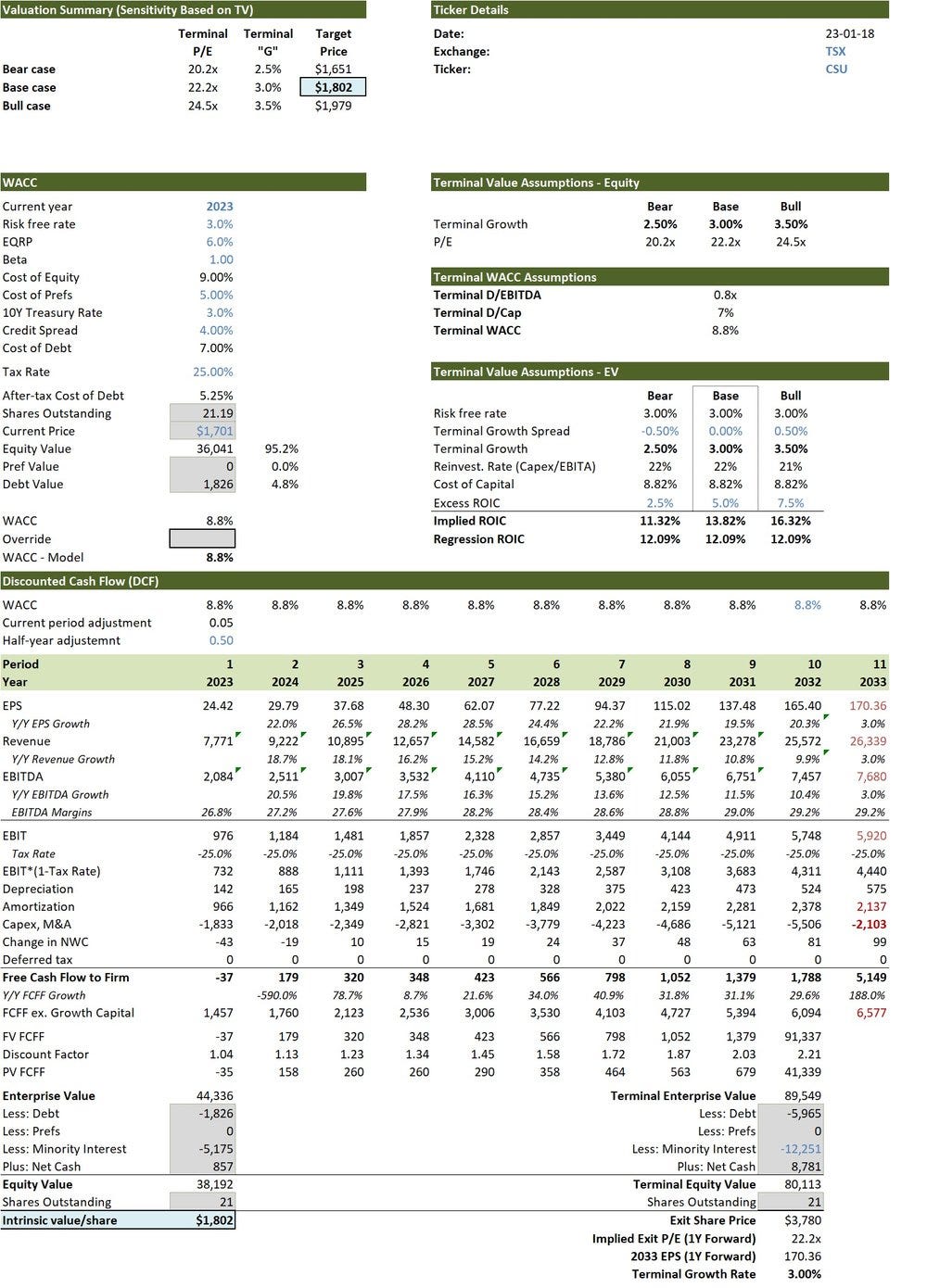

Recall my original base case suggested fair value was ~US$1,750/share in early-2020 using an 8.0% cost of equity. With nothing but the passage of time, the comparable initial base case today would be close to US$2,050/share (initial base case compounding at 8.0%). I went through and made a ton of small changes to my model, and funny enough, my new base case using an 8.0% cost of equity ended up being very close to the initial base case. But I did increase the cost of equity to 9.0%, which reduced the base case by roughly 15% to ~US$1,800/share. Excluding the change in cost of equity and CSU 2.0 assumptions, a summary of the changes I made can be found in Exhibit I.

The big things to note are that I took down EBITDA margin estimates to account for the error I made previously and the Altera acquisition. I also increased the cash tax rate modestly and kicked out any CSU 2.0 value a few years (CSU 2.0 represents ~US$70/share in my base case). Offsetting these changes was an increase in capital deployed via VMS M&A.

You can find all my estimates of key drivers in the model provided above, but the primary driver I want to elaborate on is VMS M&A. In Exhibit J I show my assumptions for acquisitions/year, average acquisition size, and the implied split between large VMS M&A (anything close to $100mn or greater) and small/midsize VMS M&A. I think the key here is that CSU will continue to scale small VMS M&A and complete many more small/midsized acquisitions/year. I think they should be able to supplement that with $850-1,000mn of large VMS M&A/year – carve-outs, the odd spin-out + large acquisition, and deals from more broker-sourced processes.

In Exhibit K I show the implied unlevered IRR on incremental VMS M&A in my base case vs what I estimate they’ve achieved/targeted for small and large VMS M&A historically. So, in the base case I have capital deployed ramping up significantly, but I also have incremental returns falling over time, and returns that are much lower than the historical average given the relatively new emphasis on large but lower return acquisitions. Despite the lower returns, this is still a better use of cash then returning capital to shareholders.

Despite completing a lot more M&A in the future, I still have CSU’s reinvestment rate (net M&A / FCFE) falling rapidly (see Exhibit L).

Either Mark succeeds at finding CSU 2.0, or a lot of capital is going to end up being returned to shareholders over the next decade. In the base case I assume that CSU finds a new place to deploy significant capital in 2025, and slowly ramps to $2.0bn/year at a 12.0% ROIC. Given the relatively low ROIC, that only adds ~US$70/share to my base case, and what’s wild about that is CSU would still accrue billions of dollars in cash over the forecast period (this is less value than I originally attributed to CSU 2.0 because I now have CSU deploying more capital on VMS M&A). It seems inevitable that they will have to start distributing capital to shareholders in just a few short years.

Exhibit N shows a snapshot of my DCF output tab. Note that I’ve only slightly changed the minority interest value attributable to TOI – they’ve deployed slightly more capital than my initial base case but otherwise my thesis there is unchanged, and an increase in the cost of equity to 9% would offset most of value accretion over the last two years (much like it did for CSU). I did change the terminal value calculation slightly to get a better proxy of true run-rate FCF in the terminal year and then applied a more accurate ROIC/reinvestment rate to this new proxy… but it didn’t make a noticeable difference to valuation.

I also think it’s helpful to outline what you’re paying for in the base case, and the waterfall chart in Exhibit O breaks out the component pieces of valuation alongside the current share price. The way I see it, the market is currently paying for just about everything except some stub value for CSU 2.0. If you think my base case estimates are a reasonable ballpark of the future, then it’s difficult to see how you could earn more than ~9%/year (the hurdle rate in my model) as a shareholder at this price.

Despite a base case that’s not materially different from the current share price using what I think are reasonable (but by no stretch layup) assumptions, I think the downside to the base case is pretty low. I ran another scenario with these adjustments:

Reduced large VMS M&A by two thirds to ~$350mn/year.

Capped total VMS acquisitions/year at 140 vs 134 last year and 200 by the terminal year in my base case. That took total VMS M&A down about 35% vs my base case, and they never complete more M&A then they did in 2022.

I kept returns on small and large VMS M&A about the same, but because of the mix shift, the weighted average IRR on M&A went up 4.0%.

I took CSU 2.0 out completely.

I took all debt out of the model.

In this scenario, which I’d feel comfortable taking the over on, I’m getting ~US$1,450/share (15% downside from the current price).

Conclusion

CSU is up ~30% from when I published the initial deep dive, and with the current share price trading more-or-less in-line with my estimate of fair value, I think it’s safe to say I no longer have a differentiated view from the market. Everything I love about this business still exists today, but the investment case isn’t nearly as compelling. Even still, I think investors could reasonably expect something around a 9% annual return from this price with what I perceive to be relatively low risk. In the absence of other great ideas, I think a position in CSU is a great way to keep the ball in play. For that reason, I continue to be a shareholder (although I’ve reduced my weight considerably in favor of other ideas).

I would love to hear from investors who feel strongly that I’m wrong – both to the upside and downside. If you have a differentiated view either way I strongly encourage you to reach out. I can be reached at the10thmanbb@gmail.com, in the comments below, or on Twitter.

Hi, I love your work - its so detailed and really helpful in understanding the business. Appreciate you making it available! I had a quick question - I don't understand why your model shows current price as 1701 formula in model (shows 2296/1.35). Would be grateful if you could explain this?