Investment Thesis

Carvana (CVNA 0.00%↑) has become the second largest used-vehicle retailer in the United States, and climbed to that podium spot after being in business for less than a decade by innovating in a fragmented and archaic industry. They were the first business to successfully execute on an e-commerce-only model, which customers seem to love (they have an 86 NPS, vs. the industry-average of low-single-digits). The company delivers vehicles directly to the consumer, and supports those sales with 100-day warranties and 7-day money-back guarantees. This eliminates a trip to the dealership and saves customers time. They also have no-haggle pricing, and have eliminated the negotiation process, which most customers hate.

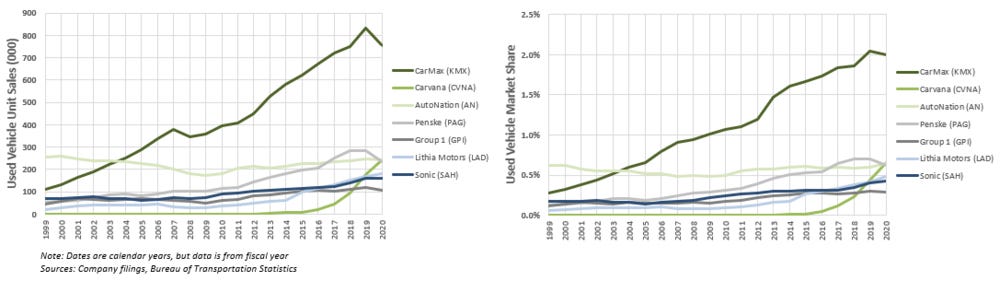

By starting from scratch, CVNA has counter-positioned incumbents by building a hub-and-spoke distribution model. Most competitors are handcuffed by existing retail infrastructure and have to take a more costly point-to-point approach to e-commerce distribution. Their unique model, which requires scale, reduces the cost associated with purchasing, reconditioning, selling, and distributing used-vehicles. CVNA splits those cost savings with consumers, which should lead to both better prices for customers and ultimately better margins than traditional retailers. The company also has multiple competitive advantages that should contribute to future market share gains, including indirect network effects, scale economies, and access to reams of valuable first-party data that they can use to continue improving the customer experience and pricing. In 2020, CVNA had a 0.65% market share, but by 2030 I suspect they could hit 4.0%, which would drive unit growth of 22%/year.

There are good reasons why CVNA has historically generated negative operating margins, but I expect operating margins to turn positive in the next 3 years, and ultimately be amongst the highest in the industry. The first reason is that GPU should increase as more vehicles get sourced from consumers, IRC utilization increases, in-house logistics utilization increases, and days to sale fall. The second reason is that SG&A/unit should fall, primarily drive by falling advertising and technology expenses per unit. In my opinion, there is good line-of-sight to all of this happening.

In addition to the core retail business, CVNA provides financing, sells service contracts and GAP waiver coverage, and sells vehicles through the wholesale channel. All of these ancillary businesses are tied to retail unit sales, but I expect that they will grow faster than retail unit sales over the next decade.

CVNA should become self-funded sometime in 2024/25, but most will most likely need to issue $1.5-2.0 bln of additional equity in the interim to offset negative near-term operating cash flow and significant capital investments. I think this is well understood.

Despite my favorable view of the business, my base case suggests fair value is $190-195/sh, which is 30% below the current price of $272/sh, and implies an IRR of just 4.0%. The expectations of key drivers implied by the current share price are substantially more optimistic than I’d be comfortable underwriting in a base case. My scenario analysis also suggests that risk is skewed to the downside. In addition, I stumbled across a number of governance-related red flags that might turn out to be nothing, but certainly give me pause. CVNA might be a compelling investment opportunity at the right price, but we’re far from that price today.

Having looked at both KMX and CVNA, I think KMX is much more compelling today, and I encourage you to check out the KMX deep dive here.

As always, I encourage you to reach out with feedback or comments if you disagree with any of my analysis. I can be reached at the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

Introduction to CVNA

In 1991, Ernest Garcia II (let’s call him Old Ernie) bought a rental car company called Ugly Duckling out of bankruptcy, and ultimately built a used-car retailer that sold and financed vehicles for sub-prime buyers. He took the company public in 1996, and then took it private again in 2002, after which it was renamed DriveTime. That company has since grown to be one of the largest used-vehicle retailers in the country (top 10 or 15).

Old Ernie’s son, Ernest Garcia III (we can just call him Ernie), received an engineering degree from Stanford in 2005, spent a few years at an investment bank, and then became the Treasurer of DriveTime in 2007. In 2012, he successfully pitched the idea for Carvana, an e-commerce-only retailer for used vehicles, and received funding from DriveTime (effectively from Old Ernie) to pursue the idea.

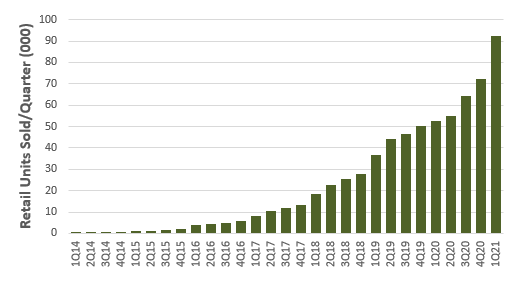

Initially, Carvana leaned on DriveTime for everything like facilities, vehicle acquisition, service contracts, customer financing, and back office functions. Ernie and the team (including co-founders Ryan Keeton and Ben Huston) also would have benefited from DriveTime guidance and know-how in those early days. The company started selling vehicles in 2013, and by the time it went public as CVNA in 2017 they were selling more than 10,000 units per quarter. Without access to those DriveTime resources, I’m not sure they would been able to scale nearly as quickly. Today, CVNA still relies on DriveTime for certain functions, like service contracts, but has clearly brought most functions and infrastructure in-house. Despite weaning off their reliance on DriveTime, CVNA has continued to grow at an astounding pace, with +90,000 retail units sold in 1Q21, up 700% from the IPO date. They are now the second largest used-vehicle retailer in the United States, and have grown faster than any other business in industry history.

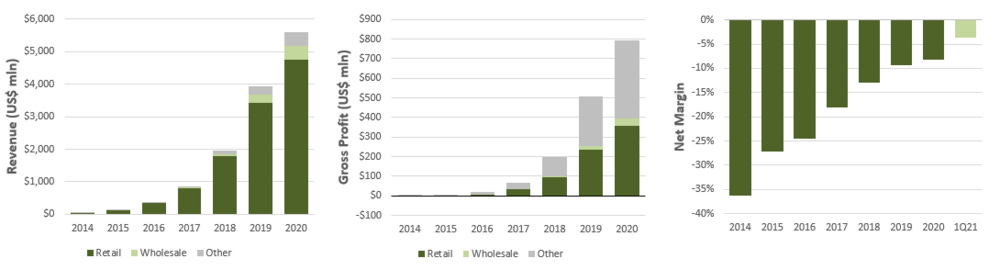

CVNA has three reportable segments: Retail, Wholesale, and Other. The vast majority of CVNA’s revenue comes from selling used vehicles to retail customers, but they also sell some vehicles at wholesale auctions and offer customer financing, service contracts, and guaranteed asset protection (GAP) coverage; collectively, Other. Although Other revenue is quite small, it contributes 50% of CVNA’s gross profit, and is therefore a very important part of the business (similar to other retailers like KMX). Despite - and perhaps because of - extraordinary revenue and gross profit growth, CVNA generates negative net income today, although margins are reaching an inflection point and I expect they will turn positive in the next 2-3 years for reasons I’ll discuss below.

Retail

As I highlighted in the KMX deep dive, the retail used-vehicle industry is incredibly fragmented. The Top 100 competitors have <10% share of total unit sales, and the largest competitor (KMX) has just 2.1% share. The vast majority of competitors operate only one dealership, and before CVNA, effectively every used-vehicle sale in the country was completed in person. I think Ernie correctly identified that A) the consumer experience at a traditional used-vehicle retailer was poor, and could easily be improved, and B) lots of customers would be fine with purchasing a vehicle online, which should be more efficient from a retailer perspective and result in better prices for customers.

The great thing about starting from scratch (which is basically what Ernie did) was that CVNA could counter-position the incumbents. They didn’t have a physical retail footprint that they would need to worry about cannibalizing, and could immediately optimize for an online-only model. Instead of building a bunch of distributed 5-acre retail sites (each of which would store a small fraction of inventory), CVNA started by building (or leasing) 100-acre inspection and reconditioning centers (IRCs). These IRCs complete all inspection and reconditioning work, but are also where CVNA stores the majority of their inventory. When a vehicle gets purchased, CVNA either transports it directly from the IRC to the consumer’s door (sometimes through a fulfillment center), or from the IRC to a vending machine for pick-up. The vending machines make the entire pick-up experience really novel (video): customers show up with a CVNA coin, insert it into the vending machine, and the car gets “dropped down” into a bay for pickup. They are minimally staffed, and even though they would be more expensive than a traditional lot, CVNA saves on some last-mile delivery costs and it also helps with brand awareness.

CVNA doesn’t have showrooms or sales teams (and are technically “open” 24/7/365), and claims that this online-only approach allows them to spend less on rent and salaries per unit sold, which are savings that they can share with customers through lower prices. My analysis shows that CVNA employees/unit sold is already amongst the lowest in industry. This distribution approach also massively reduces the number of routes, vehicles, drivers, and drive time required to deliver vehicles to customers - all of which contributes to a lower cost/unit and ultimately better pricing.

In short, CVNA built a hub-and-spoke model, while incumbent brick-and-mortar retailers that might want to build an omni-channel platform are forced to take a more point-to-point approach. KMX, which I consider to be CVNA’s largest competitor, seems to be building a hybrid model (they do have some hubs), but inventory is still predominately stored at retail sites. In Practise interviewed a former KMX sales manager who confirmed that CVNA did offer slightly better pricing in his region (Raleigh), which must be at least partly because of their differentiated distribution model. Aside from KMX and LAD, I haven’t identified a single incumbent retailer that has A) built a half-way decent omni-channel platform, and B) can effectively compete with the CVNA hub-and-spoke model at scale. In my view, CVNA has built a great competitive edge for serving online buyers; small single-location retailers have no chance at replicating this model because they lack scale, and most large incumbents are handcuffed by existing infrastructure, at least in the medium term.

Ten years ago, effectively 100% of used-vehicle retail sales were conducted in-person, and I think there was initially some skepticism that customers would be willing to purchase vehicles online (sight unseen and no test drive), even if logistics were nailed down and pricing was better. I think that skepticism was well founded. Aside from housing, a vehicle is typically the largest consumer purchase, and it’s psychologically difficult to fork over $20k (typical ASP) for something you can’t test drive, let alone touch and feel. To break down that psychological barrier, CVNA had to do five things differently from most traditional retailers:

They needed a better way of presenting inventory online, so that customers could get a clear and transparent look at exactly what they’d be purchasing (minimize the expectations gap on delivery). CVNA purchased and built technology to enable 360 degree interactive viewing of both the exterior and interior of the vehicle (doors open and closed), which included hotspots that made it easy to identify and click through features and imperfections. They also have technology that standardizes photo backgrounds so that every vehicle looks like it’s in a showroom. This sounds small, but it has a big impact on conversion, and is a huge improvement over the standard photo display on a traditional dealer website. KMX actually copied many of these same ideas as they built out their own omni-channel platform.

They needed to have exceptional quality control. The worst outcome for CVNA in the early days would be a string of customer reviews complaining about lemons. Customers need to be confident that any purchase through CVNA would meet a high quality bar. That quality control starts at the very top of the funnel; they use reams of data to avoid (by bidding accordingly) purchasing vehicles that have been in accidents, have too many miles, or raise any other potential red flags that might lead to a problem shortly after the vehicle is sold. Every vehicle that does get purchased is sent to an IRC where it undergoes a 150-point inspection. If the vehicle doesn’t pass the inspection, or requires too much additional capital to fix, CVNA immediately directs it to their wholesale channel (it never gets presented in retail inventory). Even for vehicles that pass the inspection, CVNA typically pours $1,000-1,500 of labor and parts into reconditioning. Every vehicle that moves through this process and is sold through the retail channel is also backed by a 100-day/4,200 mile “Worry Free Guarantee” (basically a warranty). Over time, this system has helped build a reputation for high quality used-vehicles, and even though many large incumbents have a similar process/warranty, it’s not common amongst the long tail of small competitors that facilitate 90% of transactions every year.

They needed to address the fact that customers couldn’t test drive the vehicle before purchase. So, in place of a test drive, CVNA has a 7-day return policy on every vehicle sold, no questions asked. Not only will CVNA deliver the vehicle directly to your door (eliminating a trip to the dealership), but if you don’t like it, they will literally pick it up right from your house. This clearly helps deliver peace of mind when a customer initially makes a purchase sight unseen.

They needed to make it seamless and fast for customers to sell a vehicle online, particularly because that’s a prerequisite for most customers looking to purchase a vehicle. Traditional retailers require that you bring your trade in down to a lot for someone to inspect, and clearly CVNA can’t do that if they don’t have retail sites. It would also disrupt the flow/value of purchasing seamlessly online. So, CVNA feeds a ton of first-party and third-party data into an algorithm that automatically determines an offer for a vehicle (I’ll expand on this a little more further down) that’s guaranteed for 7 days. This process takes 2 minutes (on average), and requires only basic information from the customer.

And finally, the traditional used-vehicle retail experience typically involves a salesperson and a negotiation. CVNA had to do away with both of those things. They needed to present no-haggle prices in an à la carte way for the vehicle, additional services (VSCs and GAP), and financing, otherwise shopping online would be a nightmare. This à la carte no-haggle pricing strategy eliminates the need for negotiations, which makes the shopping experience more transparent and customer-friendly. Funny enough, this is a best practice that KMX pioneered many decades ago in physical retail, but is surprisingly rare among most small retailers to this day (although many large competitors have followed suit).

In my view, CVNA delivers a seamless and customer-friendly online car buying/selling experience, and the model seems to be working well, particularly as COVID forced a change in buying behavior (a CarGurus survey found that 61% of consumers would be open to purchasing a car online today, versus just 32% pre-COVID). Exhibit D shows historical unit sales and market share for the 7 largest public competitors in the space, and CVNA is clearly growing orders of magnitude faster than the rest. In 1Q21, CVNA sold 92k units, and is likely on track to sell 400k+ in FY2021. In my view, COVID is permanently accelerating the adoption of used-vehicle e-commerce, and CVNA is definitely the best positioned to capitalize on these shifting preferences. Some traditional B&M competitors, like KMX and LAD, have built out omni-channel capabilities to compete with CVNA for online sales, but the vast majority haven’t done so yet, and are nowhere close to replicating what CVNA can offer. In addition, CVNA’s net promotor score (NPS) sits somewhere in the 80-85 range (self-reported), while the NPS of other competitors ranges from -10 to 16.

I estimate that CVNA’s aggregate market share in 2020 was 0.65% (and will probably reach 1.0% in 2021), but the company also reports market share by cohort, which gives us a glimpse at where aggregate market share might go in the future (Exhibit E). The 2013, 2014, and 2015 cohorts only include 1, 2, and 6 new markets respectively, which makes for pretty small samples, and therefore lower-confidence inferences about the broader market. On the flipside, the 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 cohorts included 23, 41, 61, and 120 new markets respectively. Data from those early cohorts suggests that aggregate market share per market should easily exceed 2% after 10 years from first launch, while data from more recent cohorts shows that penetration is accelerating in each new market they open. If nothing else changes, this cohort data seems to suggest that CVNA, in aggregate, might reach 3.5-4.0% market share by 2030 (40 quarters from now).

As the fastest growing retailer, and now one of the largest, I think CVNA has a handful of competitive advantages that should continue driving some combination of expanding margins and accelerated market share gains:

CVNA is a marketplace for used vehicles (you can sell and buy vehicles on the platform), and I think this marketplace benefits from indirect (cross-group) network effects. As more customers sell cars directly to CVNA, the selection of vehicles on the site increases. Breadth and depth of selection is one of the most important features of a marketplace from a buyers perspective. As a greater portion of vehicles sold get sourced directly from consumers, CVNA can also sell vehicles for slightly less than competitors (this is the cheapest source of used vehicles, which I’ll expand on later). So as selection increases and prices fall, buyer utility goes up, and more customers purchase vehicles from CVNA. As more buyers use the platform, CVNA can afford to purchase more vehicles from sellers at competitive prices, so seller utility goes up. As a business that matches supply and demand (by temporarily taking ownership of inventory), each side benefits when liquidity on the other side increases.

As unit sales increase, CVNA benefits from economies of scale. In particular, as order density increases, CVNA can simultaneously improve delivery times and reduce the per unit cost of delivery/transportation. Part of that comes from bringing logistics in-house, and part of it comes from increasing utilization of facilities and transportation infrastructure. In addition, advertising, technology costs, and headcount per unit should also fall as total units increase. I’ll expand more on this below.

CVNA collects data on all transactions, which they use to improve the customer experience, pricing, and vehicle acquisition efficiency. This first-party data is a treasure trove that can’t be replicated by the long tail of small competitors.

Used-Vehicle E-Commerce

I think there are great arguments to be made that buying/selling cars online can end up being cheaper and more convenient for consumers, and to the extent that consumer preferences shift in that direction, CVNA is well positioned to service that demand. The million dollar question, in my mind, is really: what percentage of consumers will ultimately favor the full e-commerce approach over the traditional brick and mortar or hybrid experience?

When I add up all the e-commerce units being sold by CVNA, VRM, KMX, AN, LAD, etc., I get an estimate that implies e-commerce penetration in the used-vehicle space for 2020 was in the 1-2% range. E-commerce penetration of total retail was closer to 20% in 2020, and some categories, like books, apparel, and electronics would be much higher than this (50%+). A classic bull argument points to this much higher e-commerce penetration to say “hey, used-vehicles could get there too”. While I think e-commerce penetration in this industry will end up being much higher than 1-2%, I think that there are some good reasons it might be a slow ramp, and might not ever reach the same penetration as other categories. Buying a used vehicle is a huge purchase, and lots of consumers might start the car buying experience online, but ultimately enjoy seeing vehicles in person and test driving multiple vehicles before making a decision. For example, ~50% of consumers test drive more than 1 vehicle before making a purchase, and that’s just easier to do in person. Many others might be uncomfortable making a large purchase like this online. I don’t think that will change.

I’m inclined to think that e-commerce penetration in this industry won’t exceed 15% by 2030. If CVNA’s market share (of total units) hits 4.0%, which seems likely after looking at the cohort data, then they’d be facilitating >25% of all e-commerce unit sales in this scenario. It’s hard to justify that they’ll be able to take significantly more than this; within the e-commerce space they compete with incumbents (KMX, LAD, AN, etc.) and other e-commerce businesses like Vroom and Shift. Even though CVNA is well positioned to service e-commerce demand, there is sufficient competition to prevent a winner-take-most outcome, in my view. Even still, a 4.0% market share by 2030 seems reasonable given their competitive position.

Retail GPU

Gross profit per unit (GPU) is a huge determinant of profitability for used-vehicle retailers. I believe there are four key drivers of GPU, and will explore each of them below:

Share of retail units purchased directly from consumers vs. wholesale auctions

IRC utilization

In-house logistics utilization

Days to Sale

1. Share of retail units purchased directly from consumers vs. wholesale auctions

Used vehicle retailers primarily purchase their inventory from wholesale auctions or directly from consumers. The sale price of a vehicle is the same regardless of where it was purchased, but the purchase price at wholesale auctions tends to be much higher than the price paid for a direct consumer purchase. That’s because the wholesale auction clips a fee, the vehicle gets transported further (cumulatively), and the retailer who is selling the vehicle at auction (typically already purchased from the consumer) might also earn a small margin. As a result, sourcing vehicles directly from consumers has a fairly large positive effect on GPU. Estimates vary, but the GPU on a customer-sourced vehicle seems to be $600-1,000 higher than the GPU on a vehicle purchased at a wholesale auction.

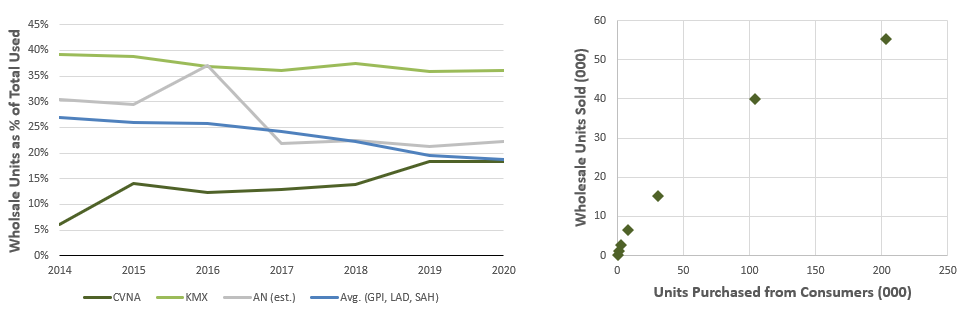

Although CVNA doesn’t directly report what percentage of their retail unit sales get sourced from customers, they do publish an annual car buyer report for consumers which details how many units they purchase in a year. I assume that most units CVNA sells back through the wholesale channel were those purchased from consumers that don’t meet CVNA standards, and can therefore back into the portion of retail unit sales that were sourced from consumers (Exhibit F). Not only has direct-from-consumer share increased by ~10x from 2017-2020, but CVNA now sources more vehicles from consumers than other big competitors like KMX and LAD. In 3Q20, CVNA sourced ~80% of retail sales from consumers and generated a record GPU of $1,860 as a result. That record GPU is higher than the average GPU for the biggest retail competitors in the space. We can also see that when the proportion of units sourced from consumers fell in 4Q20, so too did GPU.

There are boundless anecdotes roaming around in the ether indicating that CVNA pays more to purchase consumer vehicles than other retailers, and a common bear thesis goes something like: “CVNA isn’t profitable because they pay to much for inventory, and that’s not sustainable”. I would counter by saying that they weren’t initially profitable (for lots of reason), but that this has been a remarkably good strategy as they’ve scaled total unit sales and increased the share of vehicles coming directly from consumers. CVNA can pay consumers more to purchase their vehicle by splitting the savings from cutting out all the middlemen from the wholesale channel. It’s a win-win, and customers get a great first experience with CVNA, which increases the odds that they’ll also purchase a vehicle from them and become a repeat customer.

I suspect CVNA will continue to source more vehicles directly from consumer than most big competitors, and might even see that share increase over time, which should support comparable or better GPU in the future. In my view, there are three reasons for this:

Online instant appraisals/offers made easy: after providing a VIN, license plate, and answers to a few simple questions, CVNA will provide a firm offer for a customers vehicle. This entire process takes less than 2 minutes, on average. This fast, transparent, and convenient process saves time and eliminates the negotiation process, which most consumers don’t enjoy. Some large competitors also do this, but most small ones don’t.

Convenient pick-up at home: If a customer decides to accept the offer, they can schedule a time to have the vehicle picked up at their home and receive payment. Again, this eliminates a trip to the dealership. Most competitors that purchase vehicles directly from consumers, even if the offer is received online, require that the vehicle is dropped off at one of their retail locations (KMX requires this). CVNA incurs some incremental costs for this last-mile transportation (probably $50-100/unit), but that’s more than offset by the extra margin they receive from sourcing vehicles directly from consumers versus purchasing them at a wholesale auction.

Using data to generate competitive bids for in-demand vehicles: CVNA uses first-party and third-party data to get a detailed understanding of demand (nationwide) for vehicles based on make, model, trims, colors, features, and price bands. They compare demand to existing inventory to determine gaps in supply, which helps their algorithms determine how much to bid for new vehicles (more for big supply gaps, and less for small supply gaps). When the customer is providing the VIN, license plate, and other details about the vehicle, CVNA is simultaneously taking that data and feeding it into the algorithm, which will bid appropriately to match supply and demand. The algorithm also determines expected transportation, reconditioning, and depreciation costs, which impacts the offer. This incredible use of data and technology, combined with a nationally managed inventory pool, allows CVNA to bid competitively for high demand vehicles, and is clearly a competitive advantage relative to most traditional auto retailers.

2. IRC utilization

After CVNA purchases a vehicle, they bring it to one of their inspection and reconditioning centers (IRCs). All reconditioning work gets completed here, and most vehicle inventory sits at an IRC until a customer purchases the vehicle. From 2013-2016, CVNA entered into lease agreements for partial occupancy of 3 IRCs from DriveTime. From 2017 to 1Q21, CVNA built new IRCs where they were the sole occupant, and assumed 100% of capacity at most IRCs leased from DriveTime. In Exhibit G, I show historical utilization based on the full capacity of IRCs; figures from 2018 to 1Q21 should be representative of actual occupancy, while data before 2018 reflects capacity of the IRC not controlled by CVNA. In any event, I think it’s clear that CVNA has consistently utilized less than 60% of their owned IRC capacity, which makes complete sense. They open new IRCs in anticipation of unit growth, and I estimate that it takes a couple years before that capacity gets fully utilized at any given facility. I suspect that utilization will remain relatively low so long as capacity additions and unit sales growth remain high.

Utilization has a direct impact on GPU because of the partial fixed-cost nature of the facilities. I also suspect that the variable cost of reconditioning falls as utilization increases, because CVNA can more efficiently manage reconditioning work. As growth slows and utilization of IRC capacity increases, GPU should increase. It’s difficult to know what that GPU uplift could look like, but results from a few different multi-linear regressions suggest that GPU could increase by >$400 if IRC capacity ultimately exceeded 90%. The data is messy, so this is a low-confidence estimate, but my 90% confidence interval is probably $300-600. CVNA will probably choose to share some of those savings with consumers, which would strengthen their competitive position and drive even higher unit sales (and/or lower CAC), but I expect them to retain some portion of those savings and GPU to increase modestly as a result.

3. In-house logistics utilization

There are three primary transportation legs in this business. First, CVNA has to transport vehicles from the point of acquisition to the IRC. Second, CVNA has to transport vehicles between IRCs and fulfillment centers or vending machines. And third, they deliver vehicles directly to consumers. The first expense gets reflected in cost of sales (GPU), while the second and third components are expenses reflected in SG&A.

CVNA leans on a combination of third-party and in-house transportation infrastructure. Third-party providers tend to be more expensive and have less reliable delivery times, so CVNA has made an active effort to build out their own fleet. When vehicles get transported to the consumer, CVNA uses a branded single-hauler delivery vehicle ($75k/unit), but for all other transportation they use large multi-car haulers ($250k/unit; typically 9-10 cars). When those multi-car haulers have just one or two vehicles on them, the per unit cost of transportation is really high (depreciation, gas, and driver salaries are mostly fixed costs), but when they are fully utilized the per unit cost of transportation falls dramatically. In 2018, Ernie observed that for the first few months after they enter a new market, these multi-car haulers typically only have one vehicle on them. I estimate that it might take up to a year before the CVNA-owned multi-car haulers reach full capacity in a new market. I also estimate that CVNA initially leans on more third-party providers when they enter a market (more expensive) and transition to the in-house fleet as the market matures.

For all these reasons, I believe GPU in new markets is lower than more mature markets. CVNA defines a “market” as a metro area that they have commenced at home delivery. Exhibit H shows that they’ve ramped up the markets they serve significantly in recent years, up more than 500% and 80% from the end of 2017 and 2019 respectively. Exhibit H also shows the number of markets that are <12 months old, which should be a reasonable (inverse) proxy for logistics utilization. By the end of 2020, CVNA estimated that their existing markets serviced 74% of the U.S. population, which tells me that market expansions should slow in the near future. This should drive a combination of lower reliance on third parties and increased utilization of in-house logistics infrastructure, which should support a combination of GPU expansion, SG&A leverage, and additional customer savings.

4. Days to Sale

The final driver of GPU is days to sale, or the number of days CVNA holds inventory before it’s sold. Since inventory depreciates, GPU will increase as inventory gets turned around faster. Reducing days to sale also spreads fixed facility costs (IRCs, fulfillment centers, and vending machines) across more units, which also helps improve margins. CVNA has reduced days to sale by 65% over the past few years, which has clearly contributed to GPU expansion, but still sits at the high end of the peer group range (Exhibit I). As the second largest used-vehicle retailer in the country with nationally pooled inventory, best-in-class data and technology, and growing consumer awareness, I expect that CVNA will ultimately be able to reduce days to sale by another 10-20 days. For every 10 days they can reduce inventory turnaround, I estimate that they can add $100-150 to GPU, assuming they shared none of that benefit with consumers (which they would).

Summary

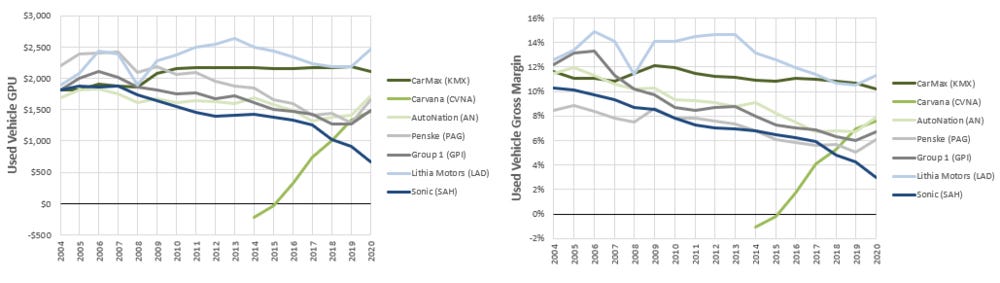

Based on my analysis of key GPU drivers, I think it’s clear why CVNA’s GPU started so low and has increased so rapidly as they’ve scaled. Exhibit J shows that CVNA’s 2020 GPU (and gross margin) was more-or-less in-line with the large peer group average. I also think it’s clear that GPU should continue to rise as they source more vehicles from consumers, increase utilization of IRCs, increase utilization of in-house logistics, rely less on third-party logistics, and reduce days to sale. CVNA frequently says that they save consumers $1,000-1,500 on the average vehicle purchase relative to traditional retailers, and even if they increase customer savings in the future, I think it’s reasonable to expect that GPU should ultimately be amongst the highest in industry.

Wholesale

Vehicles that don’t meet CVNA’s standards for retail distribution are sold through wholesale auctions. All large retailers rely on the wholesale channel to dispose of vehicles that they won’t - or can’t - sell otherwise, and the vast majority rely on third-party auction providers like Manheim and ADESA. There are really only two exceptions: KMX has managed a first-party wholesale auction for decades, and AN just started running first-party auctions in 2017. Exhibit K shows historical wholesale gross margins for all the big public competitors that report it, and what I find really interesting is that wholesale gross margins for competitors that rely on third-parties is effectively nil (GPI, LAD, SAH, and pre-2017 AN), while first-party wholesale auction margins are just shy of 20%. What I find very impressive is that even though CVNA relies on third-party auction services, they generate much higher gross margins than other competitors who also rely exclusively on third parties. In my view, this is a good indication that CVNA does a much better job at purchasing and managing inventory than competitors (accurately matching supply/demand). They do this by leveraging data and technology better than the rest, and I don’t see that changing any time soon.

I also compared wholesale unit sales as a percentage of all used-vehicle unit sales (retail + wholesale) in Exhibit L. Proportionally, CVNA is selling a lot more units through the wholesale channel today than they have historically (1Q21 was >22%), and is finally selling a proportionally similar amount of wholesale units as the non-KMX peer group. And that makes total sense. Most units sold through wholesale channels are sourced from consumers, so as CVNA ramped up purchases from consumers they were bound to have more units available to sell through the wholesale channel. If they continue to ramp up purchases from consumers, I suspect wholesale unit sales will continue to proportionally increase, and should end up higher than the non-KMX peer group.

At first glance, a fair base case assumption for the wholesale business might be that CVNA continues to earn high-single-digit gross margins and generate unit sales that are 20-25% of total used vehicles sold. But upon closer look, I think CVNA might ultimately see gross margins and proportional wholesale unit sales much closer to KMX. To get there, I think they would need to start their own first-party wholesale auction business, and build out more IRC capacity.

The first limiting factor required to build a first-party wholesale auction business is volume. KMX sells nearly 500k vehicles through their own wholesale auctions every year, and has been selling more than 100k units/year for decades. They move enough volume to hold weekly or bi-weekly auctions at 70+ physical locations around the country. Big competitors that still rely on third-party auctions sell somewhere between 30-60k units/year, so the volume threshold before first-party makes sense is somewhere north of that. CVNA sold 40k and 50k wholesale units in 2019 and 2020 respectively, but is on track to sell more than 100k in 2021. In my view, they are finally selling enough wholesale units to make a first-party business a real possibility.

The second limiting factor, at least historically, was the physical infrastructure. Pre-COVID, the vast majority of wholesale auctions were conducted in-person, and auction providers would need a dedicated space to conduct the auction. KMX was able to leverage their massive dedicated used-vehicle retail footprint to conduct auctions, but most other competitors don’t have that capacity, CVNA included. That’s all changing. During COVID, most auction businesses (Manheim, ADESA, KMX, etc) moved everything online, and it seems to be working just fine (if not better). I see no reason that CVNA couldn’t build out their own online wholesale auction platform over the next few years. They’d also be able to leverage their in-house logistics network to deliver vehicles to dealers (something KMX has talked about as a differentiator), which might make online auctions even more appealing to dealers than traditional physicals auctions.

Finally, in order to proportionally double wholesale unit sales (from 20% of the total to 40%, which is in-line with KMX), CVNA would need much more IRC capacity. The management team has repeatedly said that the primary constraint to growing retail unit sales is IRC capacity, and they’ve worked hard to increase that by 5.0x over the last five years. Retail GPU is roughly 2.0x higher than wholesale GPU, so CVNA would definitely prefer to save IRC capacity to move a retail unit versus a wholesale unit (both require time in an IRC). As retail unit growth slows down, and CVNA continues to add more IRC capacity, they should end up with more room to process wholesale units. When that happens, they should be able to purchase even more vehicles directly from consumers, even if they know those vehicles are destined for the wholesale channel. In my view, this is something that could take many years to happen, but is almost inevitable.

Other

A substantial portion of CVNA’s gross profit comes from providing financing, service contracts (VSC), and GAP coverage. CVNA lumps all of this together in Other, but with a little guesswork I can break out financing revenue/gross profit from everything else (Exhibit N). Even though these businesses are directly tied to retail units sold, they’ve seen much higher revenue and gross profit growth than the core retail business over the last few years, even as retail GPU increases.

Customer Financing

This is definitely the most complicated part of the business, at least from a reporting perspective. It’s also really important to understand, because it likely makes up ~30% of gross profit. When CVNA provides financing to a customer, they are originating a loan (recorded as a finance receivable origination). To fund that loan, they initially lean on short-term lending facilities, but ultimately sell the loan to other parties at which point it becomes non-recourse to CVNA (recorded as a finance receivable sale). Those other parties typically pay more than book value for the loan, because they’ll earn a positive net interest margin over the term of the loan (typically 60+ months). That excess payment is recorded as a “gain on sale of auto finance receivables”, and this is the primary contributor to financing revenue on the income statement, which happens to have 100% gross margins.

The two primary drivers of financing revenue are gross profit per vehicle financed (gain on sale per loan), and number of vehicles financed. First, I backed into total vehicles financed by dividing total finance receivable sales by retail units sold. Exhibit O shows that CVNA now provides financing for 75% of retail units sold, up from just 57% in 2014. The increase in financing penetration has contributed to significant historical revenue and gross profit growth, but I suspect that penetration is slowly approaching the steady state. KMX, which has a more mature financing business, tends to finance 75-80% of their retail unit sales, which I view as the theoretical ceiling for CVNA.

With an estimate of total vehicles financed, I could back into gross profit per loan by dividing the gain on sale of auto finance receivables by total vehicles financed. Exhibit P shows that gross profit per loan has increased by 100% in the last five years, but is still 32% ($575) lower than the comparable figures for KMX.

If the average credit quality of the CVNA finance receivables is comparable to KMX (and I have no reason to suspect that they wouldn’t be), then I’d expect gross profit per loan to eventually reach $1,500-1,700, which would be 25-40% higher than it was in 2020. There are two primary reasons that they aren’t there yet. First, CVNA hasn’t been originating and selling loans for very long, and the receivables therefore have a short track record to evaluate. As a result, buyers of those loans likely have a higher implicit cost of funding than they would for the KMX loans (asset-backed securities). In time, I suspect CVNA will prove that their receivables are of equivalent quality, and the appetite from buyers will increase (which decreases the cost of funding and increases the price paid). The second reason is that CVNA has historically relied on a very limited pool of buyers, while KMX has lots of third-party partners and a large established asset-backed security investor base. For example, prior to 2017, CVNA relied exclusively on DriveTime to purchase receivables, and in 2017 and 2018 they relied almost exclusively on Ally Bank and Ally Financial through the MPSA and Master Transfer Agreements. In 2019, CVNA introduced their own securitization program, and in late-2020 they also started funding receivables with fixed-pool loan sales. As they introduced new competition for receivable sales, gross profit per loan increased substantially. In my view, CVNA will continue to grow the number of channels through which they can sell receivables, which increases competition and should result in higher gross profit per loan. It’s also possible that CVNA’s gross profit per loan actually exceeds the comparable figure for KMX, since KMX pays $150/loan in payroll expenses (finance associates at retail sites) that CVNA wouldn’t have to by virtue of originating all loans automatically online.

It’s important to recognize that CVNA is currently heavily reliant on Ally, and if that relationship deteriorated it could have a large impact on their ability to provide financing to customers. The Ally MPSA has been amended multiple times to increase the maximum receivables that Ally will agree to purchase. The current MPSA, amended in March 2021, states that Ally will purchase up to $4.0 bln of receivables through March 2022. The previous MPSA stated that Ally would purchase up to $3.0 bln of receivables from March 2020 to March 2021, and most of that capacity was used up. I think it’s very unlikely that the MPSA doesn’t continue to roll and get increased over time, but this is a key risk to monitor until CVNA adds new partners/channels.

In addition to receivable sales, CVNA is required to hold a 5% beneficial interest in securitized assets, and also holds finance receivables for sale that come with the related net interest margin, provision for loan losses, etc. These are relatively small balances, with a largely immaterial impact on gross profit. They can fund the majority of these on-balance-sheet interests with dedicated secured credit facilities. I therefore don’t expect any future changes in finance receivables for sale to impact their funding position materially.

All told, revenue and gross profit from customer financing is directly tied to retail unit sales, and should grow slightly faster than retail unit sales over the next five years as both financing penetration and gross profit per loan increase.

VSCs and GAP

Like all used-vehicle retailers, CVNA offers service contracts (VSCs) and GAP waiver coverage to customers. They offer these products on behalf of third-parties and receive commissions without any associated future obligations. The majority of VSCs and GAP waiver coverage is administered by DriveTime, which is considered to be a related party. I think the DriveTime relationship has historically raised some eyebrows, but I can’t find any evidence to suggest that the CVNA receives commission rates from DriveTime that are materially different from competitive market rates.

If my estimates for customer financing revenue are correct, then we can back into VSC/GAP revenue per retail unit sold. Exhibit R shows that that VSC/GAP revenue per retail unit has increased threefold since 2017, and is now higher than the comparable per unit revenue at KMX. What most likely happened is that the attach rate of VSC/GAP has increased significantly, and that the actual VSC/GAP fee per vehicle has remained more-or-less flat. In 2020, the VSC and GAP attach rates at KMX were 60% and 20% respectively. I can’t prove it, but I suspect that attach rates are better online than in-person (so better for CVNA than KMX), particularly because CVNA makes it possible for customers to personalize VSC and GAP options without a salesperson looking over their shoulder. Nevertheless, not every customer will want a service contract, and even fewer actually need GAP coverage, and attach rates are probably approaching a steady state at CVNA. In the near future, I expect that VSC/GAP revenue per retail unit will plateau and total VSC/GAP revenue will start to grow in-line with retail unit sales.

EBIT Margins

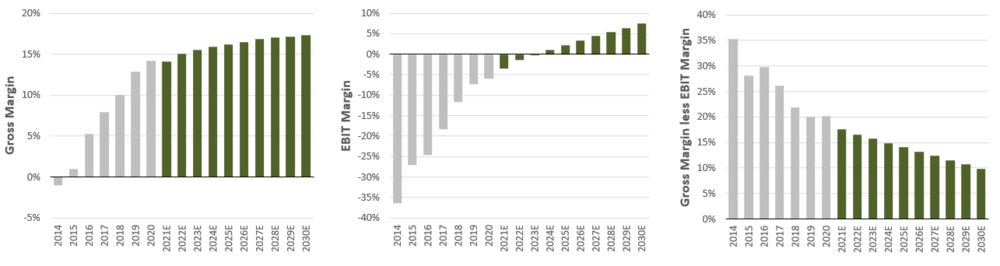

Gross margins have improved significantly since inception, but EBIT margins have improved 2.0x faster as CVNA scales, which indicates that CVNA is realizing leverage on cost items like payroll, advertising, technology, and occupancy (collectively, SG&A).

There are two ways to measure this improvement: expenses as a percentage of total revenue, and expenses per retail unit sold. Exhibit T shows both methods, and contrasts those expenses to the comparable figures from KMX. Despite the significant reduction in expenses through either lens, CVNA still spends substantially more than KMX in most categories. In my mind, the big question here is whether or not CVNA can eventually reach KMX-level efficiency, and I primarily think about this in terms of $/retail unit sold since most expenses are tied to selling retail units.

Compensation expense per unit has already decreased by 35% since 2014, and is now in-line with KMX. Both companies employee 30-35 employees per 1,000 retail units sold, which is already at the low end for this industry (AutoNation is more like 45-50, for example). There is probably some room for this to continue improving as IRC and logistics utilization increases, but I suspect most of the low-hanging fruit here has already been grabbed.

Advertising expense per unit has decreased by 45% since 2014, but is still 4.0x higher than KMX. Average ad expense per unit for CVNA in 2020 was nearly $1,200, but the cohort data shown in Exhibit U shows that spending in older cohorts is significantly less than this; the 2020 average was dragged up by the all the new markets that CVNA entered in that year (the 2020 cohort was $1,652). When CVNA enters a new market, awareness is low and they spend aggressively to address this. As markets mature and more consumers learn about CVNA, ad spending per unit falls. Since CVNA has such a high NPS, it’s quite likely that word-of-mouth marketing helps drive down ad spend/unit as markets mature. In addition, vehicle purchases are relatively low-frequency, and the vehicle fleet turns over about once every 4-5 years. A great initial customer experience might lead to a repeat purchase with negligible incremental ad spend after 16-20 quarters, which is another reason that ad spending per unit likely falls as markets mature.

It’s also important to recognize that a significant portion of ad spending should be categorized as growth capex. The National Automobile Dealer Association (NADA) shows that typical dealership ad spend has historically worked out to ~1.0% of revenue, and this cohort is only growing unit sales by ~1%/year. CVNA spent 5% of revenue on advertising in 2020 (5x the average dealership), but grew unit sales at 37% last year. Against that backdrop, it’s very likely that “sustaining ad spending per unit” is actually 80% lower than the headline figures I calculated. That being said, there are some puts and takes that make CVNA different from a typical dealership. On the one hand, they don’t have a large physical retail presence, which is effectively free advertising. On the other hand, I’ve anecdotally heard that CVNA has a top-notch performance marketing team that probably earns a much higher ROI on ad spend than less sophisticated competitors. They also build brand awareness in markets where they have vending machines, which are much more likely to grab a commuter’s attention than another vanilla used-vehicle lot. It’s difficult to pin-point exactly where ad spending per unit might shake out in 10 years, but there are many compelling reasons to expect that it will end up being 70-80% lower than spending last year. This should contributed to relatively significant margin expansion.

Market occupancy and logistics expenses are a miniscule portion of the total, and while they’ve decreased proportionally over time, I don’t expect any changes in the future to impact EBIT margins in a major way. That leaves us with “other”. CVNA doesn’t explicitly break out the components of other, but the biggest expense here is probably technology and related compensation. Roughly 25% of CVNA’s annual capex is capitalized software spending, and this line item has grown nearly five-fold in the last three years, which is consistent with the growth rate in other expenses. It’s hard to get a great apples-to-apples comparison of technology spending between CVNA and other competitors, but my analysis suggests that CVNA is spending more in absolute terms on technology than any other competitor, including KMX. Despite what I estimate to be high spending, other expenses per unit have still fallen by 40-45% since 2014. This is the single largest expense item at CVNA today, but I think that economies of scale should continue driving this per unit expense down significantly over time, particularly since there is some upper limit on how many new features and site/process improvements they can make. Other expenses also include corporate occupancy and various fixed cost items that shouldn’t increase materially as unit sales grow. Even if proportional spending remains higher than peers like KMX, I think it’s likely that other per unit costs can fall by 60-80% over the next 5-10 years.

All told, I think there is clear line of sight to at least a 30-40% reduction in combined SG&A per unit, and more likely a 40-50% reduction if SG&A per unit ends up in-line with KMX. All else equal, I think this SG&A improvement should result in a 9-10% increase in EBIT margins from 2020.

Financial Position and Ownership

Funding

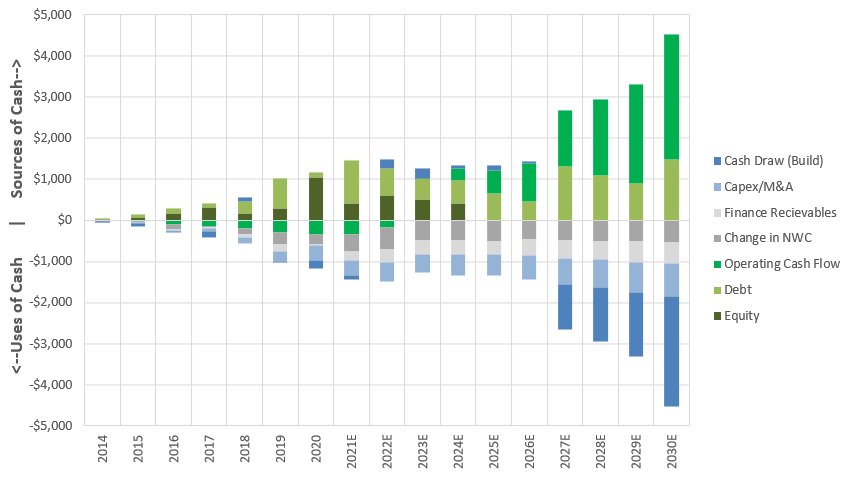

Exhibit V shows historical sources and uses of cash at CVNA, and it’s clear that they have relied heavily on new debt and equity to fund growth: operating cash flow has been negative since inception; net working capital (primarily inventory) investments are significant; and, run-of-the-mill capex has increased every year as they build facilities, the logistics network, and software.

On the debt front, CVNA relies on a combination of asset-backed financing and unsecured notes. Exhibit W shows how total debt has changed over time, and the composition of that debt. To better understand future funding, it’s worth exploring some of these financing levers in more detail:

At the end of 1Q21, CVNA had $1.7 bln of senior unsecured notes outstanding that come due between 2025 and 2028. The first set of notes they issued in 2018 charged interest of 8.875% for a 5-year term. Each subsequent issue has seen some combination of lower rates and longer terms. The last set of notes issued in March 2021 had a 6-year term and charged interest of 5.500%. I’m certainly not an expert here, but it appears as if the appetite for CVNA debt has improved significantly, and they’ve been able to easily raise new debt every year since 2018.

Effectively all of their NWC investments are tied to inventory growth, and CVNA has a $1.25 bln Floor Plan Facility (LIBOR + 2.65%) that technically could be used to fund their entire inventory balance (I’m just calling this “Inventory” in Exhibit W). Pre-2020, CVNA had funded roughly 80% of their inventory with this facility, but by year-end 2020 they were funding just 4% of inventory through this channel, leaving 97% of the facility undrawn ($1.21 bln). I suspect that they paid down the facility with proceeds from the senior unsecured notes issued in 2020/21, but will probably draw on it in the future. This is an important pool of liquidity that should help bridge any near-term funding gap, and is a commonly-used facility amongst competitors.

Finance receivables held for sale and beneficial interest in securitizations totaled $400+ mln at the end of 2020 and $560 mln at the end of 1Q21. CVNA has short-term credit facilities with $1.0 bln of capacity at sub-3.0% interest that are meant to fund these balances, but which remain largely unused today. Much like the Floor Plan Facility, I suspect CVNA has avoided drawing much on these facilities by issuing senior unsecured notes, which have much longer terms. Nevertheless, these are commonly utilized funding tools in industry, and should be an important future source of funds.

The vast majority of capital expenditures are tied to IRCs, vending machines, fulfillment centers, and the transportation fleet. At the end of 2020, CVNA had funded 65% of these investments through sale-leaseback transactions, which get treated as debt on the balance sheet (“Transportation fleet” and “Real estate” balances in Exhibit W). These transactions have initial terms of 20-25 years, and typically have 25-year renewal options and options to repurchase the asset. In the near-term, I expect that CVNA will continue to rely heavily on sale-leaseback transactions as a funding mechanism, but will probably end up repurchasing assets once operating cash flow becomes sufficiently positive.

The way I see it, CVNA should easily be able to fund the vast majority of NWC, finance receivables, and capital expenditures with securitized (asset-backed) debt, and most of these funding sources remain largely underutilized since they’ve been able to raise unsecured notes. This significantly reduces near-term funding risk.

We’re still left with negative operating cash flow and capex that they don’t fund with debt, which CVNA has historically funded by issuing new equity. Since going public in 2017, the fully-diluted Class A share count has increased by 27%, and CVNA has raised nearly $2.0 bln in the process. In my base case, I think CVNA will start generating positive operating cash flow in 2023 or 2024, but probably wouldn’t be totally self-funding until 2025. In the meantime, I think they’ll continue to issue new equity, and my best guess is that they will need to raise an additional $1.5-2.0 bln over the next 3-4 years. At the current share price, they would need to issue something like 8.0 mln new Class A shares (5% dilution). In my view, this is probably well understood by the market, and if properly accounted for, I don’t think it’s a big deal.

Share Structure

The ownership structure of CVNA is a little complex, but I’ve mapped it out in Exhibit X. The publicly listed entity (CVNA) has listed Class A shares and unlisted Class B shares. The Class A shares hold 100% of the economic interest in CVNA, while the Class B shares only have voting rights. CVNA itself is a holding company for the Carvana Sub, which in turn owns 44% of the outstanding LLC Units in Carvana Group (where all the assets are located). In effect, public shareholders held a 44% economic interest in Carvana Group at the end of 2020, and the remaining 56% is held by the LLC Unitholders. The LLC Unitholders are effectively the Garcia family, and in combination with their Class A shares, the Garcia’s control roughly 90% of all votes at CVNA.

LLC Unitholders have an Exchange Agreement with CVNA whereby they can exchange LLC Units for Class A Shares at a ratio of four-to-five, but must also simultaneously exchange Class B shares at a ratio of one-to-one which get immediately cancelled. At the end of 2017, CVNA Class A shareholders held just 13% of the outstanding LLC Units in Carvana Group, but by the end of 2020 they held 44% of the outstanding LLC Units, and the increase in ownership was primarily driven by conversion of LLC Units by LLC Unitholders.

Exhibit Y shows the historical split in ownership of LLC Units and Class A shares, including the fully diluted Class A share count if all LLC Units held by LLC Unitholders were to be exchanged. Note that the aggregate increase in LLC Units and fully-diluted Class A shares is a function of secondary equity issues. When I value CVNA, I ignore the minority interest calculation and instead use the fully diluted Class A share count (you could use basic Class A shares and factor in minority interest instead, but the outcome would be the same).

Management & Governance

As a controlled company, the Garcia family is driving the bus and public shareholders are just along for the ride. Sometimes this is a good thing, and sometimes it isn’t. In this particular instance, I stumbled across a number of red flags that, when combined, raise some concerns:

The Garcia family and a few other insiders control 90% of the votes at CVNA, and Old Ernie directly controls 27% of those votes.

Old Ernie is the controlling shareholder of DriveTime, and CVNA engages in multiple related-party transactions with DriveTime.

There may be circumstances where the interests of LLC Unitholders (mostly the Garcia family) and Class A shareholders are in conflict, and the controlling shareholder (Garcia family) might make decisions not in the best interest of Class A shareholders.

Old Ernie has a checkered past. In 1990 he pleaded guilty to bank fraud charges, and in 1999 he was sued for allegedly abusing his position to profit from a real estate deal with Ugly Duckling (which ultimately became DriveTime). That 1999 lawsuit was settled, but it’s not a good look, particularly since he controls CVNA and DriveTime, and may have interests at odds with Class A shareholders. There are plenty of criticisms levied at Old Ernie for past dealings, and it’s nearly impossible to ignore as an outsider looking in.

The Garcia’s and multiple directors are being sued (full document here) for a direct equity offering in March, 2020 at “bargain basement prices” in “an offering that was only open to company insiders and certain existing investors”.

To sum it up, there is some evidence to suggest that one of the controlling shareholder of CVNA has A) a history of questionable dealings, and B) is in a position to make decisions that may benefit LLC Unitholders at the expense of Class A shareholders. Even though I can rationalize that some of these flags are misguided (like the lawsuit from last year), they still give me pause.

All that being said, I love Ernie (the CEO). From all the interviews and transcripts I’ve digested, Ernie comes across as thoughtful, curious, and not afraid to swim against the current. He also clearly cares deeply about CVNA’s customers, employees, and reputation. I think Ernie has crafted a unique culture at CVNA, NEO incentives and overall compensation (which he would have a hand in crafting) check all the boxes that I’d typically look for, and I can’t find any explicit red flags in the proxy statements. In my opinion, he’s done an excellent job at innovating in a stagnant industry, and shows no signs of slowing down. He was interviewed in 2017 at a venture conference, and I’ve included that interview below because I think it does an excellent job at peeling back the onion on how he thinks and what he values. If the transgressions from Old Ernie didn’t exist, I’d have no qualms trusting Ernie with my capital.

Recent fillings indicate that Ernie controls a much larger share of the votes at CVNA than his father, which I view as a good thing. As a founder-CEO who is not yet 40 years old, I think he has a multi-decade runway ahead of him at CVNA, and he definitely understands that future success is going to depend not just on satisfying customers and employees, but also equity and debt holders. As LLC Units convert to Class A shares, I also think some of the potential misalignment between public shareholders and insiders dissipates. Despite some of the red flags I’ve stumbled across, I think the risk that Ernie fails to act in the best interest of shareholders is really low. All else equal, I’d still probably require a slightly higher return to own CVNA than a comparable business without the hair.

Valuation & Scenarios

Retail

In the base case, I assume that CVNA’s market share in the retail used-vehicle space reaches 4.0% by 2030, up four-fold from what will most likely be about 1.0% in 2021. I expect that CVNA will sell ever-so-slightly more vehicles than KMX by 2030, and ultimately end up as the largest used-vehicle retailer in the country. Consumer preferences are changing and more consumers are likely to purchase vehicles online, particularly since they are likely to save both time and money by doing so. In my view, CVNA is best-positioned to capitalize on those shifting consumer preferences, and most competitors won’t be able to offer a comparable selection, quality, speed, consistency, ease-of-use, and price. At the same time, many consumers will still prefer the in-person shopping experience, and I would be shocked if total e-commerce penetration in the used-vehicle market exceeded 15% by 2030. There will also be some e-commerce competition from KMX, LAD, Vroom, Shift, and a few others, so it’s difficult to see how CVNA market share (e-commerce-only) meaningfully exceeds my base case estimate. In any event, the range of outcomes here is relatively wide, which makes scenario analysis extremely important.

As the business scales, and growth slows, I expect that GPU will continue to improve as IRC and logistics utilization increases, inventory days fall, and more vehicles get sourced directly from consumers. In the base case, retail GPU hits $2,200 by 2030, which is more-or-less in-line with KMX today (and would be at the high-end of the peer group).

These estimates drive revenue and gross profit growth of 23.5%/year and 27.0%/year respectively over the next decade, which compares to the trailing 3-year CAGR of 81% and 122% respectively.

Wholesale

I suspect that CVNA will ultimately introduce a first-party wholesale business, purchase more vehicles directly from consumers, and build enough IRC capacity to accommodate more wholesale volume. So even though wholesale unit sales are closely linked to retail unit sales, I expect that wholesale units as a proportion of the total will increase from 18% and 22% in 2020 and 1Q21 respectively, to 35% by 2030. This would be proportionally lower than where KMX is today, but would still make CVNA one of the largest wholesalers in the country.

Wholesale ASP jumped significantly in 2020 on the back of a tight wholesale market, which contributed to a 45% increase in wholesale GPU for CVNA. ASP and GPU reached record highs in 1Q21, but I suspect this will normalize post-COVID. Even still, wholesale GPU at CVNA has increased consistently over time for many of the same reasons that retail GPU increased, and I expect that trend to continue over the next decade. In the base case I take wholesale GPU up to $900, which assumes that they build a first-party wholesale auction business. This would be in-line with KMX wholesale GPU today.

These estimates drive revenue and gross profit growth of 29.0%/year and 38.0%/year respectively over the next decade, which compares to the trailing 3-year CAGR of 150% and 164% respectively.

Other

Much like the wholesale business, Other revenue is a direct function of retail units sold; however, I think that there are multiple reasons to suspect Other revenue will grow faster than retail unit sales. In particular: even though VSC and GAP penetration is likely nearing the steady-state, I think it will continue to increase for another 5+ years; similarly, I think total vehicles financed by CVNA can continue to increase modestly from 74% in 2020; and finally, gross profit per vehicle financed should increase for all the reasons I outlined earlier in this piece. My base-case KPI forecasts are shown in Exhibit AD.

Combined, these forecasts drive revenue (and therefore gross profit) growth of 25%/year over the next decade, versus a trailing 3-year CAGR of 129%. The best part about these businesses is that they require little-to-no incremental capital investments, and proportionally less SG&A than the Retail and Wholesale businesses.

EBIT Margins

Exhibit AF shows my base case forecast for each SG&A expense item (inclusive of DD&A) on a per-retail-unit basis. I think it’s reasonable to expect that compensation per unit has very little room to improve from here, and that changes in market occupancy and logistics expenses per unit aren’t overly material. On the flipside, advertising and other (technology/corporate occupancy) expenses should see significant improvements as expansion into new markets slows, existing markets mature, and the business scales. I expect that SG&A/unit will ultimately come down 40-45% from 2020 levels. I show this forecast vs. the trailing 3-year average S&GA/unit for KMX, and even though these aren’t perfectly comparable figures, I find it to be a helpful goal post to measure against.

Through a combination of gross margin expansion (higher retail/wholesale GPU) and lower SG&A/unit, I think it’s reasonable to expect that EBIT margins should turn positive in the next 3 years, and ultimately reach mid-to-high single digits by 2030 (I assume ~7.5%).

A 7.5% EBIT margin may not seem high, but it would be a clear outlier in this industry. Exhibit AH shows my 2030 CVNA margin forecast versus the pre-COVID trailing 5-year average for the public peer group. For a variety of reasons, this isn’t a perfect apples-to-apples comparison, but it’s close enough to provide some context for the base case. The CVNA approach (which counter-positions incumbents) should reduce the expenses incurred to purchase, recondition, sell, and distribute vehicles, and they should be able to split those cost savings with consumers. I’m therefore comfortable assuming industry-leading EBIT margins in the base case. This is most likely a contentious view, and I encourage you to reach out if you disagree.

Capex, Funding, and Minority Interest

In the base case, I expect that operating cash flow (before changes in NWC and finance receivables) will turn positive in 2023, and increase rapidly thereafter. In the meantime, CVNA needs to continue building out infrastructure, investing in NWC, and funding finance receivables held for sale. Much of this funding should come from securitized (asset-backed) debt and cash currently on the balance sheet. Even still, there is an obvious funding gap that most likely needs to be filled with new equity. In the base case, I assume that CVNA issues $1.9 bln of equity over the next four years at an average price of $220/share (5% dilution).

By 2030, the base case assumes that steady-state D/EBITDA (excl. inventory and finance receivables financing) is 1.5x, which would be at the low end of the comparable historical range for the peer group. In this scenario, CVNA would accrue $7-8 bln of cash, and I assume that they earn exactly their cost of equity (8% in my model) by distributing that cash through systematic buybacks or dividends. It’s possible that they find new creative ways to deploy that capital at higher returns, but that’s something I’ve decided to reflect in the bull case rather than the base case. Exhibit AI shows the component pieces for sources/uses of cash in my forecast.

Finally, rather than calculate and deduct minority interest from total EV, I instead divide total EV by the fully-diluted Class A share count. This should reflect the proportional economic interest of public equity shareholders in Carvana Group. I also treat all future stock-based compensation as a cash cost.

Tying it all together

Combined, the base case has revenue growing at 24%/year over the next decade. By 2030, CVNA is the largest used-vehicle retailer in the United States, selling 1.8 mln retail units. They also end up as the most profitable, with 7.5% EBIT margins (and a higher EBIT/unit than peers). ROIC exceeds 20% by 2030.

Exhibit AJ shows a screenshot of the DCF output tab, but the full model can be found here. In the base case, I estimate that fair value is $190-195 per fully diluted Class A share, which is 30% below the current share price of $272/share. Put differently, the implied IRR at the current share price is just 4.0%.

The assumptions behind my bear and bull case scenarios can be found in Exhibit AK. The return to my bear and bull case is -71% and 26% respectively, which works out to an implied IRR of roughly -7% and 10%. In my view, risk is meaningfully skewed to the downside.

Finally, I wanted to more specifically back into what the current share price implies for some of these key drivers. To set my DCF equal to the current share price, which implies an 8% IRR, I have to assume that:

CVNA market share hits 5.0% by 2030, which works out to 2,242k retail unit sales (a 25% CAGR from 2020). For context, KMX, which is the largest used-vehicle retailer today, sold 750k units last year and is guiding to 1,200k units by 2025. My own estimate is that KMX might sell 1,600-1,700 units by 2030. The read-through is that CVNA will become the largest used-vehicle retailer by a wide margin, and have much more success with their e-commerce-only approach than competitors like KMX will have with the hybrid omni-channel approach.

Retail GPU hits $2,400 instead of $2,200, which would be the highest in industry and 40% higher than the 2020 peer group average. It would also imply that CVNA is probably keeping most of the cost savings from their model (sharing less with consumers). It seems unlikely that they’d be able to grow retail unit sales at 25%/year without sharing more of those savings with consumers.

SG&A/unit would have to be the lowest in industry. Combined with higher GPU, CVNA would have a 8.4% EBIT margin. This is >2.0x higher than the average EBIT margin for the peer group pre-COVID.

I’m open to the idea that CVNA might achieve these market share, GPU, and SG&A/unit milestones, but my own assessment tells me that the probability is low. I love this business, but can’t comfortably underwrite these assumptions to justify this as an investment today, particularly with some of the governance concerns I outlined earlier.

This looks like a good one to add to the watchlist.

I feel like a "what went wrong" update is in order here!