Investment Thesis

Carmax (KMX 0.00%↑) is the largest used-vehicle retailer in a highly fragmented industry. Their market share sits at 2% today, while the Top 10 and Top 100 retailers have a combined share of just 5% and 8% respectively. Most of their competitors are small single-location dealerships, and KMX has a long list of competitive strengths and advantages over this cohort, which include:

Differentiated customer experience, defined by no-haggle pricing, quality standards, and a unique commission structure for associates

Better unit economics as a function of scale and a strategically distributed store footprint, which can lead to lower prices

Wide selection of vehicles and a nationally-managed inventory pool

Rare omni-channel and logistics capabilities

Strong brand and advertising prowess

Largely unparalleled data, analytics, and technology

KMX has seen market share increase nearly seven-fold over the last two decades, and as they grow, many of these competitive advantages compound in importance. In particular, as consumer preferences change and online car-buying grows in popularity, KMX is one of just a handful of competitors that can effectively service that demand. As a result, I think KMX is well positioned to continue taking share from small competitors for decades. My expectations for retail unit growth significantly exceed those implied by the current share price.

Most large competitors (Top 10) have copied some KMX best practices, but are unlikely to effectively replicate many of their competitive advantages, specifically when it comes to omni-channel and logistics capabilities, and data, analytics, and technology. A small handful of competitors like CVNA might prove to be exceptions to the rule, but the industry is sufficiently fragmented that multiple large retailers can continue to win in tandem for a long time.

KMX has also built first-party wholesale and financing businesses that are tied to the hip of retail unit sales; something very few competitors have been able to do. These complimentary businesses generate significant gross profit with very little incremental capital, and contribute to industry-leading ROIC and ROE. As retail unit sales grow, so too should these businesses. There is also compelling evidence to suggest that both the Wholesale business and CAF (first-party financing) might grow faster than the Retail business. I don’t think KMX gets any credit for this today.

Lastly, equity ownership amongst the management team and a large portion of regular employees is quite high. Everyone appears to be rowing in the same direction as investors. I would characterize the management as great operators but average capital allocators, and wouldn’t expect any meaningfully accretive M&A or opportunistic buybacks. But that’s okay. Excess cash is likely to be returned to shareholders through systematic buybacks, and I expect that KMX could likely repurchase 30% of their float over the next decade, all while maintaining lower leverage than peers and still growing operating income at 8-9%/year.

In the base case, I estimate that fair value is $173/share, which is 45% higher than the current price of $118/share, and implies a 10-year TSR of 12%. My bear and bull case scenarios also suggest that risk is meaningfully skewed to the upside ($109/share and $238/share respectively). In my view, the current share price represents an attractive opportunity to own a high-quality business that dominates in a fragmented industry.

As always, I encourage you to reach out with feedback or comments if you disagree with any of my analysis. I can be reached at the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

Intro to CarMax

CarMax (KMX) operates the largest used-vehicle retail business in the United States, and has four reportable segments. Exhibit A shows the historical revenue and gross profit contribution by segment (note that fiscal year-end is Feb 28, so fiscal 2021 is effectively calendar 2020): Retail and Wholesale is self explanatory; CAF is short for CarMax Auto Finance, which is a first-party auto finance business; and, Other includes third-party auto financing fees, a small amount of new vehicle sales, service revenue, and fees from extended protection plans (EPPs).

Before diving into each segment it might be helpful to take a holistic look at how they all fit together (Exhibit B). KMX acquires vehicles from retail sellers, leasing companies, rental companies, dealers, and wholesalers. They evaluate each vehicle to determine if it meets the internal standards required to classify it as CarMax Quality Certified. Only vehicles that meet this standard are sold through the retail channel (often after modest reconditioning/maintenance), and the wholesale channel acts as an outlet for all the vehicles that don’t make the cut. The average age of vehicles sold through the wholesale channel is about 10 years (>100,000 miles), while the retail channel typically sells cars 0-10 years old. KMX originates financing for more than 75% of retail vehicles sold, either directly through CAF or through a network of third-parties. The remaining ~25% either don’t require financing or secure it elsewhere.

Retail

Competing in a stagnant and fragmented market

The U.S. vehicle fleet (measured by registrations) grew by 1.2%/year from 1990-2019, while population growth averaged 0.9% over the same period. Ownership per capita increased. Despite more vehicles in circulation, total vehicle sales in 2019 were roughly the same as total sales in 2000, and used vehicle sales were slightly lower in 2019 than 1995.

As a result, used vehicle turnover fell from 20% in the 1990s to <15% in recent years (measured as used vehicle sales divided by vehicle registrations in period). One contributing factor is that average vehicle age has increased substantially over the last 2-3 decades; as vehicles last longer, they tend to be held longer (Exhibit D). The bad news is that the used vehicle pie hasn’t changed for two decades, so average growth in unit sales for the industry over that period was roughly 0%. The not-as-bad news is that used vehicle turnover has started to plateau. If turnover remains constant, then used-vehicle sales might grow at ~1%/year in the future. If turnover continues to fall as vehicles last longer, than used-vehicle unit sales growth might be nil.

Against this backdrop, it’s reasonable to expect that the majority of unit growth for companies like KMX will have to come from increasing market share rather than any secular industry tailwind. And that’s exactly what KMX has done for 30 years. Used vehicle unit sales went from 111k in fiscal 2000 to >800k pre-COVID (CAGR of 11% vs. industry at 0%), and market share went from 0.3% to 2.0%.

KMX is now the largest used-vehicle retailer in the United States, selling 3.0x more units than their next closest competitor. I’ll expand on the largest competitors further down, but I’d like to first draw your attention to Exhibit F. Automotive News publishes a list of unit sales by dealership group, and while KMX clearly dominates in this space, the Top 10 competitors had a 2017 market share of only 4.6%, while the Top 100 had a market share of just 7.8% (2020 splits should be similar, if not slightly higher). This is a very fragmented industry, with 40,000+ dealerships and 18,000 franchised dealers, not to mention private sales. NIADA data confirms that >90% of all dealership competitors had just one location. As we think about KMX’s competitive position, we should start by understanding how they compete with the long tail of single-location competitors.

Unique Customer Experience

The first CarMax store opened its doors in 1993, and the business was a subsidiary of Circuit City until 2002 when it was spun out as an independent public company. At that point, they had 35 used-vehicle stores in 10 states. By the end of fiscal 2021, they had expanded to 220 used-vehicle stores in 41 states. Most of this growth was organic, and Exhibit G shows that growth was a function of both expanding into new states and increasing penetration in each of those states. In my view, one reason they’ve been able to do this so successfully is by offering a differentiated customer experience.

Most surveys show that people generally don’t enjoy the car-buying experience; they don’t trust car salespeople and they don’t like the negotiation process. Anecdotally, I can attest to this. The KMX approach fixes a lot of these problems by doing a few things differently:

Most salespeople in the industry are paid a commission based on the gross profit of a sale, which includes additional services and interest margins on the car loan. KMX salespeople are paid a fixed-dollar commission per unit sold, regardless of which vehicle is purchased, how the vehicle is financed, or which additional services you buy. This structure changes the incentive from “squeeze every penny out of the consumer” to “get customers the right vehicle for them”. Right from the start, I believe this leads to a higher-trust customer experience. If they had done nothing else differently, I believe this single change to the business model would have driven higher market share.

Most people sell an existing vehicle to purchase another one. They have to negotiate twice, which is time consuming and uncomfortable. In many cases, dealerships only accept trade-ins, which means the customer is also obligated to purchase a vehicle if they want to sell one, and are therefore beholden to the prices and selection of a single dealership. KMX fixes that by separating the purchase and sale decision: “we will appraise a customer’s existing vehicle free of charge and make a written, guaranteed offer to buy that vehicle regardless of whether the owner is purchasing a vehicle from us”. This no-haggle offer is good for seven days. I’ll expand on this further down, but KMX has high inventory turnover, scale, and data that allow them to offer no-haggle prices that are consistently competitive. This all improves the customer experience, which builds trust and increases the likelihood that they also purchase a vehicle from KMX, even though they aren’t obligated to.

The same no-haggle pricing structure is also applied to KMX vehicle sales, products and services, and financing. They present fixed non-negotiable prices and terms for each component of the car buying process, and the prices and terms of any one component aren’t dependent on those of other components. Customers can choose to purchase a vehicle at the presented price, and simultaneously elect not to purchase other products/services or use KMX for financing. This eliminates another part of the negotiation process and improves transparency, which increases trust and convenience.

KMX also has a high quality-bar for their used-vehicle inventory. Every vehicle they retail is reconditioned to meet the CarMax Quality Certified standards, and when that’s not possible, they sell the vehicles through wholesale auctions. They give retail customers the ability to take 24-hour test drives before committing to a purchase, and also provide a 30-day/1,500-mile money-back guarantee. This high quality-bar and commitment to “getting it right” for the customer sets them apart. At KMX, customers don’t need to worry that they’re buying a car from Danny DeVito.

By doing a few things differently, I think KMX has built a trusted brand, reduced friction in the car-buying/selling process, and generally improved the customer experience. This contributes to KMX selling way more vehicles per store than their competitors (Exhibit H), although there are additional reasons for this which I’ll touch on further down. What’s equally impressive is that even as KMX expands into new states and increases penetration in existing states, they’ve managed to maintain meaningfully above-average unit sales per store. If I use units sold per acre (to adjust for the fact that the average KMX store has gotten smaller), we can see that this metric has been effectively constant over time.

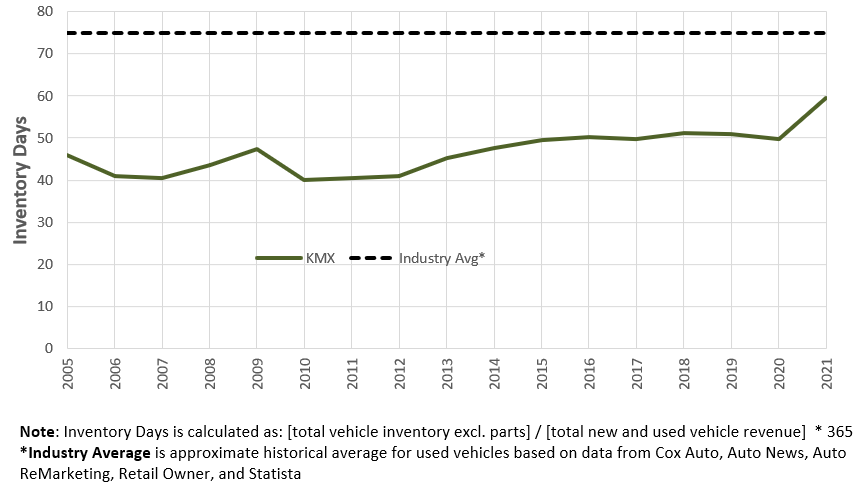

Another more conventional way to look at this is “inventory days”, which adjusts for any differences in new and used vehicle mix. Ignoring fiscal 2021, KMX has much lower inventory days than my estimate of the industry average over time (they turn over inventory 50% faster than the average).

There are three primary benefits from high inventory turnover (more units sold per store):

Lower occupancy cost (rent, building depreciation) per unit

Lower headcount per unit

Lower inventory depreciation per unit

The first two benefits are obvious, but the third is more nuanced. Used-vehicle inventory depreciates at ~15%/year, so the longer it’s held, the lower a retailers’ gross profit per unit (GPU). Using the KMX average selling price (ASP) and GPU in fiscal 2020, I show how GPU changes at various inventory day and inventory depreciation rate assumptions. If KMX inventory days were in-line with the industry average, their GPU would have been 10% lower in 2020, and since this is such a low margin business, their net income would have been 25% lower (3.5% vs. 4.5%). Data from fiscal 2021 supports this idea, where GPU fell as inventory days increased, roughly consistent with the 15% depreciation curve below.

In my view, lower occupancy expense, headcount, and inventory depreciation all result in industry-leading profitability, which helps KMX reinvest in their business and take share from competitors. This has directly contributed to KMX’s historical success. Now that KMX is the largest used-vehicle retailer in the country, I think they’ve also built a number of competitive advantages (many stemming from scale) that should help accelerate growth in the future.

Advantage #1: Strategically expanding footprint drives even lower occupancy and payroll expenses per unit

Every used vehicle that KMX purchases has to undergo an inspection and reconditioning process. Through this process, they determine which vehicles can be CarMax Quality Certified and sold through the retail channel, versus those that don’t meet the cut and should be sold through wholesale auctions. All of that inspection and reconditioning work gets completed at “production stores”, which have lots of service bays and tend to be quite large (10-35 acres). Given the size of these lots, KMX also hosts all their wholesale auctions at production stores. In the early-2000’s, when KMX penetration per market was low, most of their stores were production stores. As the company increased penetration in existing markets, they disproportionately opened “non-production stores”, which don’t have reconditioning capabilities and tend to be much smaller (4-12 acres). The data in Exhibit K shows that KMX has pretty consistently maintained 2.0-2.5 production stores in each state they enter, while non-production stores per state has increased by nearly three-fold. This is clearly a very conscious hub-and-spoke approach to reconditioning and distribution, and I would expect to see growth in non-production stores continue to outpace growth in production stores as KMX increases penetration in existing markets. In fact, KMX plans to open an additional 10 stores in fiscal 2022, with the majority to be non-production locations.

But why is this important? Well, multiple non-production stores in a region can lean on a centralized production store to complete reconditioning, which creates a meaningful scale advantage for KMX because it reduces headcount per vehicle sold (which I believe was already low at the beginning of the century). Exhibit L shows that KMX headcount per 1,000 retail units sold fell by 25% from 2005 to 2020 (2021 was impacted by COVID, but I’d expect to see that trajectory resume). The relationship between proportional non-production store count and employees per 1,000 retail units sold is quite strong, and while there are a few other drivers of lower headcount/unit, I think this is a clear indication of a scale advantage. Relative to small used-vehicle dealers that might only have one or two locations, this should lead to A) higher operating income per unit, which can be reinvested in technology and marketing, and indirectly lead to higher market share, and/or B) better prices, if KMX shares some of this scale benefit with consumers, which can more directly lead to higher market share. So far, KMX seems to be doing the latter.

Advantage #2: Wider selection of vehicles

KMX can offer consumers a much wider selection of vehicles than 99% of competitors, and breadth in selection is an important component of the consumer experience. This has always been true, but has become increasingly important in a digital world. Most surveys show that 70-90% of consumers begin the car buying process online, where they research vehicles, research prices, and ultimately find actual cars listed for sale. When I search for used vehicles at local dealerships, I’m typically presented with 200-400 choices. When I go to carmax.com, I can search a national inventory of ~30,000 vehicles. With KMX, it’s much easier to find the make, model, year, mileage, and features I’m looking for then if I painstakingly searched the sites of 10 small local dealerships.

It’s also important to recognize that consumers can purchase any vehicle from KMX’s national inventory - it doesn’t need to be on the lot of a dealership in your city/region.

“Upon request by a customer, we will transfer virtually any used vehicle in our inventory. This gives CarMax customers access to a much larger selection of vehicles than any traditional auto retailer. In fiscal 2021, approximately 38% of our vehicles sold were transferred at customer request”

In my view, the fact that 38% of vehicle sold were transferred at customer request is validation that breadth of selection is an important competitive advantage, which should lead to some higher market share. The cost of transferring a vehicle seems to range from free, for close distances, to $500, if across the country. It would appear that the median shipping cost borne by the consumer for a transfer is probably $100-200, which works out to <1% of the average selling price for KMX vehicles. With so many units moving around the country, I suspect the average shipping cost per unit would also be lower than almost any other competitor that might entertain a similar offering (some exceptions among large competitors like CVNA).

Advantage #3: Omnichannel and Logistics

In my view, the used-vehicle industry is late to e-commerce, KMX included. While it’s been possible to browse inventory online for some time (and request transfers), it was basically unheard of to complete the entire car buying or selling experience without visiting a physical dealership until five or six years ago when businesses like CVNA entered the scene. I can understand why. The industry is really fragmented with lots of local competitors in every market, and it doesn’t make sense for a single-location dealership in Detroit to spend money to build out an e-commerce solution to sell vehicles off their lot to a customer in Miami. Transporting one vehicle to a new distant market every month is expensive and logistically complicated, and building out a good online platform is also expensive. That all changes with scale and/or capital.

KMX was exclusively a brick-and-mortar retailer until late-2018 when they started to roll out an omni-channel platform. They took a measured approach to rolling out the platform by starting in Atlanta (their biggest market), testing the experience, and learning how to scale across the organization. By early-2020 they had completed the rollout to all markets (just as COVID hit), but the car buying experience still wasn’t completely self-serve; customers still had to interact with associates to complete a transaction. By the end of fiscal 2021 (first calendar quarter of 2021) KMX had enabled a full self-service online buying experience for every step in the process for ~25% of their customers. By the end of calendar 2021, they expect that customers in effectively all markets should be able to complete the entire car buying experience online without having to interact with an associate, much like you would if you were purchasing toilet paper from Amazon (not that you’d test-drive toilet paper!). For context, 5% of KMX vehicles were purchased online in fiscal 2021, when the service was available to maybe 15% of customers (on average for the full year).

What’s really interesting is that it took two years of behind-the-scenes work and an additional three years of implementation for the largest used-vehicle business in America to roll out a full omni-channel experience. KMX now employs over 750 people in technology roles (up 30% y/y), and has likely spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the platform to facilitate a seamless omni-channel experience with attractive features like the ability for consumers to register their vehicle at the time-of-purchase (saves a trip to the DMV).

Technology is certainly one barrier to building a good omni-channel platform, but the bigger barrier is logistics. For customers shopping online, there are few things as important as speed, consistency, and shipping cost. To have a fast, reliable, and cost-effective online experience, you need to control a massive fulfillment and shipping network. With 220 locations, KMX has a physical lot within 60 miles of 80% of the U.S. population. They’ve also built out 26 transportation hubs in the last four years, and have reduced their dependence on third-party drivers by building up their own fleet. At the Analyst Day in early-May, KMX highlighted that they have 260 dedicated CarMax trucks and 525 drivers that moved 50% of all their vehicles in fiscal 2021, up from <20% just a few years ago. To-date, they’ve been able to reduce delivery times by 50% by in-sourcing transportation. They have plans to add an additional 100 trucks to their fleet in fiscal 2022, which I suspect will continue to improve speed, consistency, and shipping costs.

A great online platform should also help customers more easily tap a national pool of used-vehicle inventory (versus just shopping locally), which makes Advantage #3 even more important. I suspect that an increasing portion of consumers will look to purchase vehicles online in the future, and KMX is incredibly well positioned to meet that demand with a network that’s incredibly difficult for even their largest competitors to compete with. As a leader in online used-vehicle retailing, I think KMX will ultimately build up an order density that leads to a meaningful and permanent shipping cost advantage, much like Amazon did with every other consumer product.

The omni-channel approach has three other important implications for KMX.

First, they should be able to increase unit sales faster than they open new stores (sales/store should go up). In my view, the cost savings from opening fewer stores should more than offset any increased investment in trucks, and I suspect that capital intensity should fall as a result.

Second, online transactions are supported by Customer Experience Centers (CECs). KMX has reduced in-store headcount faster than they’ve increased CEC headcount, which leads to fewer associates required per unit sold. In addition, the compensation structure of in-store associates is different than CEC associates; in-store associates get paid commission on a sale, and tend to earn more than a CEC associate. As more volume moves online, less commission gets paid. So not only are fewer people required to facilitate each sale, but average compensation per associate should fall as the associate mix changes, which should lead to margin expansion. Offsetting this is the incremental cost of last-mile delivery (drivers), but I don’t expect that to be a complete offset.

Third, the omni-channel platform is outfitted with an instant-appraisal feature where customers can get a guaranteed no-haggle offer on their vehicle in under 2 minutes. They can accept the offer, deliver the vehicle, and get paid the same day. This should help KMX source more vehicles directly from consumers, which is important because those vehicles tend to have higher gross profits (I’ll touch on this more under the Wholesale section). Since launching the instant-appraisal feature in February, KMX has reached an annual run-rate of “hundreds of thousands of instant-offer buys” directly from consumers, which makes them the biggest online used-vehicle purchaser in the country (from consumers).

In my view, KMX has a great omni-channel platform and there are huge and likely insurmountable barriers to entry for most competitors in the space. I think this will accelerate unit growth, particularly because KMX intends to share most of those savings with consumers. The early data supports this, with market share in Atlanta (the first omni-channel market for them) increasing significantly in the last two years.

Advantage #4: Brand and Advertising

The used-vehicle ecosystem is notoriously “low-trust”, but KMX has built a relatively trusted brand after 30 years of doing things differently. As a result, I suspect they get more repeat and referral business than the average used-vehicle dealership, and therefore have a much lower customer acquisition cost (CAC). Exhibit M shows KMX advertising spend as a percentage of revenue, versus the same figures reported by NIADA across thousands of small dealership competitors. Even though the intensity of advertising spend has been similar historically, it’s worth noting that the average dealership is growing the top-line at just 0-1%, while KMX has grown the top-line by more than 10%. As a result, most of the spending for the average NIADA dealership is “maintenance”, while most of the spending at KMX is “growth”, which indicates that KMX has a lower CAC.

The other interesting thing to highlight from Exhibit M is that industry-wide advertising intensity fell in 2021, while KMX ramped up spending significantly. KMX has much higher net margins than the industry average, so even though margins compressed in a tough year, they had the ability to act countercyclically, which I suspect should translate into accelerated market share gains in fiscal 2022+.

One reason KMX ramped up advertising is to bring more awareness to the new omni-channel platform and some other customer-centric changes made over the last two years, like the “Love Your Car Guarantee”. They do this by marketing across multiple traditional and digital channels. For example, they have partnerships with the NBA and WNBA, and recently launched a series of hilarious commercials featuring players like Stephen Curry and Sue Bird, some of which had more than 800 mln impressions. They also do podcast sponsorships, work with influencers on social media, and partner with unrelated businesses like Dunkin’ to run campaigns like Doing Donuts. Small competitors, even those in the top 20-30, can’t afford to undertake national campaigns like this, which makes it hard to compete for customer mind-share.

The advertising prowess isn’t just a function of scale. It’s pretty clear that KMX is a very data-driven organization, and has dozens of professionals tracking returns on advertising spend. They adjust spending budgets per channel on a weekly basis to optimize that return, and their goal is to increase marketing returns every quarter by leveraging their data and analytic capabilities. They’ve also implemented the structure and processes to stay nimble and react quickly to changing environments, despite being a huge organization. The CEO, William Nash, provided a great and hilarious example of this here (start at 11:30 and watch for ~12 minutes). Again, this is a level of sophistication that most competitors don’t have the resources to achieve.

Advantage #5: Data, Analytics, and Technology

It’s worth highlighting again that KMX has meaningfully ramped up their technology teams over the last five years: total headcount went from 320 to 750+, data scientists went from 120 to 250, data engineers went from 10 to 75, and product teams went from 5 to 50. KMX simultaneously took all the disparate data they’ve collected over decades, scrubbed it, and made it easier to access and work with. These new-hires used the treasure trove of data to start building new tools, features, and actionable insights. For example, they built a centralized inventory management and pricing system that utilizes their data and machine learning to automate a number of historically tedious manual tasks:

“Our proprietary centralized inventory management and pricing system tracks each vehicle throughout the sales process and allows us to buy the mix of makes, models, age, mileage and price points tailored to customer buying preferences at each CarMax location. Leveraging our more than twenty-five years of experience buying and selling millions of used vehicles, our system generates recommended initial retail price points, as well as retail price markdowns for specific vehicles based on algorithms that take into account factors that include sales history, consumer interest and seasonal patterns. We believe this systematic approach to vehicle pricing allows us to optimize inventory turns, which reduces the depreciation risk inherent in used cars and helps us to achieve our targeted gross profit dollars per unit. Because of the pricing discipline afforded by our inventory management and pricing system, generally more than 99% of our entire used car inventory offered at retail is sold at retail.“

As the depth and breadth of their data grows, their machine-learning tools, features, and actionable insights improve. I thought the slide in Exhibit N from the Analyst Day perfectly captures this idea:

I was surprised to learn that KMX hosts hackathons and fun competitions like the Innovation Garage, where associates can dedicate a few days to work on and pitch new ideas. So far, they’ve done lots of cool stuff like:

Build a unique routing system for customers moving through the online platform that better matches customers with CEC associates. For example, if a customer has already selected a vehicle, picked an EPP, and contacts the CEC while they are at the financing section of the process, the routing system will direct the customer to a CEC associate focused specifically on financing. This might seem small, but it improves the customer experience which should translate into higher conversion.

Utilize machine learning to analyze photos taken at any location and modify the surrounding background to create a more visually appealing offering. This basically takes a photo of a car that might be in a garage with a dirty floor and industrial-looking background, and puts it in a studio environment.

Use real-time data to test the price elasticity of supply and demand in various markets across a range of vehicle types.

Personalize the customer experience by building a better vehicle recommendation engine that updates recommendations with each new piece of information it receives from the customer search process.

Improve the efficiency of inspection and reconditioning.

Add a tracking feature for online purchases.

While many of the things I just highlighted improve the customer experience, many also reduce the cost of selling used-vehicles, and KMX can share those savings with customers through more competitive prices. NIADA data shows that the average industry GPU on used vehicles has been consistently higher than KMX, and yet net margins on used-vehicle sales are effectively nil. Over the last decade, KMX GPUs have been about $200 lower than the industry average (5-10%). It’s not a perfect apples-to-apples comparison, but I think it’s directionally indicative of the KMX advantage. As an aside, CVNA’s CEO thinks that they save consumers an average of $1,500 versus a traditional used-vehicle retailer by moving the car buying process online and better utilizing technology. I’ve found no specific mention of how much KMX saves versus a traditional auto-retailer after making all the necessary adjustments, but KMX has clearly reduced the per unit cost of selling vehicles, and pricing between the two competitors seems reasonably comparable. As KMX continues to leverage their data, analytics, and technology, I expect that the cost advantage will grow.

Big Competitors

I think it’s quite clear that KMX has a competitive edge over the long tail of small used-vehicle retailers, so the next question becomes how do they stack up against some of the big competitors in the space?

The seven largest used-vehicle retailers in the U.S. are public companies, and I was able to pull historical used vehicle unit sales for this cohort going back to 1999. KMX and CVNA both stand out for different reasons, but one other takeaway that I found particularly interesting is that all of these businesses (with the exception of AN) gained share over the last 5, 10, and 15 years. As a group, the market share of these businesses went from 1.8% in 1999 to 5.1% in 2020. The rich got richer, likely at the expense of single-location dealers.

One reason that most large competitors have gained share is that they’ve copied some of the best practices at KMX, including no-haggle pricing for the vehicle purchase (some, like LAD and GPI have also been active acquirers). The KMX best-practices aren’t revolutionary, and it shouldn’t really come as a surprise that other forward-thinking businesses have copied some of them. In my view, these best practices are not durable long-term differentiators amongst the Top 10, and one day it might not be a differentiator amongst the Top 100. That being said, Customer Guru shows that the net promotor score for KMX is tied for first among the six competitors that they had NPS data for. I wouldn’t place much emphasis on these scores, but it does seem to suggest that KMX is still viewed as best-in-class by consumers.

In an interview that’s now three years old, the CEO of CVNA observed that many large used-vehicle retailers were seeing gross margin compression on used-vehicle sales, but no compression on company-wide gross margins. So I plotted both (Exhibit Q), and the delta between each. What this shows is that most large competitors are likely being more price competitive on the actual vehicle sale, but making up for that lost margin by pushing more expensive services, parts, financing, and insurance. So even though most large competitors have copied the no-haggle pricing model for the vehicle sale, they still have that traditionally thought of “pushy” sales person upselling other products. What’s fascinating about these graphs is that the gross margin for KMX at both levels has been relatively constant, and the delta between the two hasn’t changed for a decade. In my view, this is an indication that the true holistic no-haggle experience at KMX isn’t actually being properly replicated yet by most large competitors, and the customer experience is therefore not quite the same. This is likely contributing to the higher NPS score.

Moving on.

On the surface, it would appear that most top competitors have also built scale advantages, but that turns out not to be true for everyone. All of the competitors listed above, with the exception of CVNA, are predominately new-vehicle retailers. For example, PAG had 148 dealership locations in the U.S. at the end of 2020, but only 6 of these were dedicated used-vehicle centers. Most of their used-vehicle sales actually take place at franchised new-vehicle locations (+75%). As a result, most of the inventory they source tends to be trade-ins, and any given new-vehicle lot will disproportionately carry used-vehicles of the make for that franchised dealer. In my view, this makes it more difficult to manage inventory, which is exacerbated by the fact that PAG (and a few others) operate in a decentralized way that gives local operators control over inventory management and pricing.

With so few dedicated used-vehicle centers, I think it’s much more difficult to replicate the hub and spoke (production and non-production) approach that has helped drive better unit economics at KMX, and therefore likely disadvantages some of these competitors when it comes to pricing/margins (all else equal). It also makes it difficult to operate a national omni-channel platform because the physical infrastructure isn’t setup to manage the logistics like KMX’s larger used-vehicle-first network.

All that said, competition is clearly increasing. AN had only 5 dedicated used-vehicle stores at the end of 2020, but plans to open an additional 50 locations by the end of 2025, and has a long-term goal of having more than 100. SAH had just 16 dedicated used-vehicle locations at the end of 2020, and plans to open an additional 125 by 2025. These are both ambitious growth plans fraught with execution risk, but will nevertheless increase competition in the used-vehicle space. Most of these companies are also trying to mimic the omni-channel strategy, and implement online instant-appraisals to source more vehicles directly from consumers. They continue to copy what’s working for KMX, and while they are starting way behind the leader today, and some will fail, it seems likely that a few big competitors will successfully follow KMX’s lead.

At the same time, LAD is already well positioned to continue taking share. LAD is a serial acquirer (and great at it) who also happens to be generating same-store sales growth in the same ballpark as KMX. They already have a good omni-channel platform, and seem to be leveraging data and analytics nearly as well as KMX (and certainly better than many of the other large competitors).

Despite what I view as a reasonably competitive Top-10 landscape, it’s interesting to see that KMX has maintained relatively high GPU and gross margins while most competitors have seen them shrink. Despite high gross margins, KMX continues to generate organic unit growth slightly above the average for this group. This confirms my view that KMX has a strong competitive position amongst this group today. It will take time for some big competitors to built out a dedicated used-vehicle network, an even remotely comparable omni-channel experience, and build good data and technology teams and expertise. In the meantime, KMX continues to evolve. They’ve built a culture around constant innovation, while many competitors are merely copying things that work. I’d note that LAD is a bit of an odd beast, with remarkably high GPU and strong organic growth. One explanation is the vehicle mix is tilted toward higher margin units, but another is that LAD sources 60% of their used-vehicle units from consumers (vs. KMX at 40%).

All told, while KMX has some durable competitive advantages, many of their large peers are growing aggressively and are likely to mimic many parts of the KMX playbook. It’s reasonable to expect that most of these businesses will take share over the next 5-10 years. Thankfully, KMX is the leader today and isn’t standing still, and the used-vehicle ecosystem is sufficiently fragmented that each of these competitors could double market share in the next decade and still have a combined share of just 10%. This is an industry where multiple business can continue to win for a long time. In the next ten, or even twenty years, I wouldn’t expect competition amongst the Top 10 to notably impact KMX - with one potential exception.

Carvana ($CVNA)

I think CVNA deserves a special mention, and I intend to follow up the KMX deep dive with one on CVNA because of how fascinating their business is. While most large competitors have a history of copying KMX (reacting to innovations by the leader), I think KMX has made changes to their business model partly in reaction to CVNA.

Ernest Garcia, the founder of CVNA, hypothesized that the best two ways to change the sub-par car buying experience was to dramatically change the cost structure and improve the customer experience. He structured CVNA to do just that by focusing on an online-only strategy, which allowed them to: build a concentrated hub-and-spoke distribution infrastructure (ultimately lowering per unit expenses), offer free at-home delivery and pick-up (improving the experience), and utilize technology to automate the selling and buying experience (reducing cost, friction, and improving the experience). By starting from scratch, without any physical retail presence, they’ve been able to build distribution and processes in an entirely different way. They’ve counter-positioned traditional auto retailers that need to continue catering to physical retail channels or risk cannibalizing existing sales. I think this is one reason that CVNA has organically grown to be the #2 used-vehicle retailer in the United States in less than a decade, taking share faster than any retailer in industry history. I’ll expand more on this in the CVNA deep dive.

I suspect most traditional auto retailers will fail to effectively compete with CVNA, but this doesn’t mean that KMX will. At the KMX Analyst Day it’s clear that they’ve already copied many of the online car buying features that CVNA pioneered like automatic vehicle registration, 360 degree views of the vehicle exterior and interior, photo background standardization, hotspot selection, and fully automated self-service online checkout. Most other competitors haven’t yet been able to do most of these things (you can visit each of their online platforms and immediately notice the differences). KMX and CVNA also both have centralized reconditioning facilities (CVNA has IRCs, and KMX has production stores), home delivery, vehicle tracking, in-house logistics (their own truck fleet), instant appraisals, 100-day warranties and 7-day money-back guarantees (KMX just increased this to 30 days), flexible automated financing options, and personalized recommendation engines.

If KMX was ten steps behind CVNA in 2016 from a digital experience perspective, they’re probably only one or two steps behind today, and are clearly working to close whatever gap remains. As physical retail locations closed in 2020 due to COVID, and KMX hadn’t yet rolled out the full omni-channel platform, they saw retail unit sales fall by 10%. Meanwhile, CVNA grew retail unit sales by 37%. But in fiscal 2022, I think KMX is much closer to offering a customer experience that’s reasonably homogenous to CVNA, and it shows. KMX broke an internal record this March after selling more than 100,000 retail units, and indicated that this strength continued into April. CVNA is definitely the fiercest competitor in the space, but it’s encouraging to see KMX react quickly to the changing competitive landscape while few others can.

In my mind, the real long-term debate is whether an online-only or omnichannel approach is best. There is likely always going to be a cohort of customers that like visiting a physical car lot, and I’m inclined to think that having both a physical and digital presence will be important long-term. KMX should eventually have the capabilities to offer everything CVNA can, but CVNA will have a much more difficult time going the other way. Nevertheless, over the next 5-10 years I’d expect absolute unit growth to be comparable between both competitors, and I think both can win simultaneously in this fragmented market.

Wholesale

The wholesale used-vehicle market is significantly more concentrated than the retail used-vehicle market. Manheim and ADESA facilitate ~70% of all wholesale unit sales in the United States, while the KMX wholesale business facilitates just 4% of total volume.

The big wholesale auction businesses don’t take ownership of the inventory. Instead, they act as middlemen and clip a fee at the auction. According to an In Practise interview with the former VP of Strategy and Marketing from KAR Global (owner of ADESA), only 50% of vehicles offered at auction tend to actually sell in a given day. The buyers and sellers at the auction are also responsible for the shipping cost and logistics of getting the vehicles to and from the physical auction. So auction sellers might not transact and still have to spend money moving vehicles to and from the site. For these reasons, ADESA and Manheim seem to be “the two most expensive places to dispose of and purchase a used car at auction” in the United States. According to KAR financial data, the average auction and service fee per vehicle sold at physical auctions is $800-900, while the average fee for online-only auctions is $150-200 per vehicle, which excludes some costs borne by the sellers and buyers. Depending on the format, auction and related fees work out to 5-9% of the average selling price (ASP; ~$10,000) of all wholesale units. Since the retail market is such a low-margin business, this ends up being a significant cost to retailers.

This is the primary reason that KMX tries to source as much of their retail inventory directly from consumers instead of relying on auctions (40% of all retail units were sourced from consumers in fiscal 2021). Apparently, the GPU for consumer-sourced used vehicles ends up being $600-1,000 higher than the GPU for vehicles sourced through auctions.

While many of the consumer-sourced used-vehicles pass the CarMax Quality Certified standard required to be sold through the retail channel, many do not. For those ‘leftovers’, KMX is forced to resell them at a wholesale auction. Instead of relying on a third-party, KMX decided to run their own wholesale business. And the reason is obvious. While the big wholesalers facilitate transactions for all used vehicles, KMX just sells vehicles through the wholesale channel that tend to be 10 years old and have more than 100,000 miles. As a result, the ASP for KMX wholesale units is ~$5,000, which is roughly 50% lower than the ASP at big auction houses like ADESA (making the auction fees even more punitive, because some portion is fixed). KMX tends to generate a GPU on wholesale units of $900-1,000 by conducting their own wholesale auctions instead of relying on a third-party. If KMX sold these units through Manheim or ADESA, and paid 50% of the total fees, it would reduce their GPU significantly. KMX can run their own auction business because of their scale, which is another differentiating factor relative to most small competitors who have to lean on third-party providers. For some context, Sonic Automotive (SAH) is one of the bigger used-vehicle retail competitors in the United States, but relies on third-party auction services to dispose of inventory in the wholesale market. They have a similar wholesale ASP to KMX, but they actually generate a negative GPU. As a result, SAH is likely to be less aggressive about purchasing as many vehicles as possible directly from consumers, which ultimately leads to lower GPUs for their used-vehicle retail business.

KMX has historically conducted wholesale auctions at their physical production stores, and runs them either weekly or bi-weekly. What’s unique about these auctions is that KMX owns 100% of the inventory, and can lean on data and technology to update pricing quickly and make sure inventory turns over. The average auction sales rate for KMX therefore ends up being 90-95%, versus the average auction sales rate at ADESA of 50%. This reduces depreciation risk and contributes to higher GPU through higher inventory turnover. The fact that they hold the auctions at their existing retail locations also means the incremental physical investments required to make this possible are low.

During COVID, KMX moved all of their physical auctions online, and I suspect that a significant portion of auction volume will permanently shift to the online format. If ADESA is any indication, it’s possible that this drives lower GPU for wholesale units, all else equal. Exhibit S shows that historical GPU has remained relatively flat for most of the last decade, including through COVID, but that gross margins fell to levels not seen since 2015 (ASP increased by 20%). It’s possible that KMX is targeting a fixed-GPU like they do in the retail business, but I’m open to the idea that margins (and therefore GPU on normalized ASP) might be lower in the future. On the flip-side, as KMX moved their auctions online they saw a 20% increase in unique attendees, which might mean more competition and a permanently increased ASP.

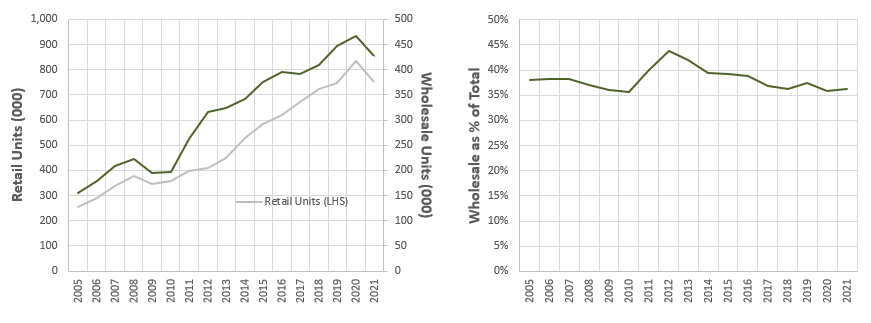

Either way, the Wholesale segment will continue to be an important contributor to gross profit for KMX. From a unit sales perspective, the wholesale and retail businesses are tied at the hip, and Exhibit T shows that wholesale units as a proportion of the total (wholesale plus retail) has been reasonably steady since 2005.

There are some early signs that KMX might be able to grow the Wholesale business faster than Retail, and take wholesale unit sales proportionally much higher than they’ve been historically. For example, I’ve already highlighted that as KMX rolled out and advertised the online instant appraisal feature, they’ve hit a run-rate of “hundreds of thousands of instant-offer buys” directly from consumers. This likely drives a greater mix of consumer-sourced vehicles for the retail channel, but is bound to also increase the number of vehicles purchased that don’t meet the CarMax Quality Certified standards, which leads to more volume through the Wholesale business.

Aside from moving more units, KMX is also exploring a few other ways to expand the Wholesale business. For example, they started a pilot program where they will transport cars for dealers who purchase a vehicle at a KMX auction. They can do this by leveraging their growing in-house logistics capabilities. This could either increase GPU for Wholesale, help them gain share in the auction market, and/or increase utilization of the truck fleet to help lower delivery costs per unit for retail buyers.

All told, I’m inclined to think that KMX can probably maintain or increase GPU while growing wholesale unit sales proportionately faster than retail unit sales over the next 5 years.

CarMax Auto Finance (CAF) and 3rd Party Financing

KMX splits their retail customers into four categories depending on how they choose to finance a vehicle: CAF, Tier 2, Tier 3, and Other. As highlighted earlier, CAF is the internal first-party financing division of KMX, while Tier 2 and Tier 3 customers are those that lean on third-party KMX partners, and Other includes those that choose not to finance the vehicle or secure financing through another channel. Exhibit U shows the historical split by category from fiscal 2016-2021 (when they started reporting the split), and CAF’s split back to 2010.

CAF is primarily focused on prime lending, which explains why net loan losses for their managed receivables tend be <1%. KMX is able to use “proprietary underwriting standards” that are informed by a combination of external and internal data to extend financing offers “designed to create a loan portfolio that meets [their] targeted risk profile in the aggregate”. When a customer doesn’t meet the threshold to be considered by CAF, KMX offers financing through third-party partners (7 at the end of fiscal 2021), which include Ally Financial, Capital One Auto Finance, Chase Auto Finance and a few others.

Tier 2 customers are typically a higher credit risk than those financed by CAF, but still reasonably profitable for lenders, and partners would therefore historically pay KMX ~$300 for every Tier 2 loan originated on their behalf. Tier 3 customers are typically much higher credit risk than Tier 2, and KMX has historically paid $1,000 per loan to partners that underwrite Tier 3 loans. Management is willing to pay Tier 3 providers because they believe that these customers wouldn’t otherwise be able to secure financing, and therefore wouldn’t be able to otherwise purchase a vehicle from KMX. If this was true for 100% of Tier 3 customers, then having this structure in place likely increases operating income by 5-10% - not insignificant.

In the fourth quarter of fiscal 2021, KMX ended up renegotiating fees with their partners: Tier 2 partners will now pay KMX $400/loan (up 33%), and Tier 3 partners will be paid $750/loan (down 25%). KMX will also fund more Tier 3 loans through CAF (target of 10%, up from 5%). Apparently the gross profit per loan originated for Tier 3 providers is more-or-less the same as Tier 1, but with a higher provision for loan losses. KMX must believe that the provision for loan losses for the incremental Tier 3 loans they fund must be less than the $750 fee they pay to partners. Aggregate industry data suggests this is probably the case. All told, these small changes should increase run-rate operating income for the entire company by 3-4%.

For the core CAF business, nearly 100% of auto loans are funded through a securitization program (non-recourse debt). KMX earns the spread between interest income on the loans and the interest expense on the asset-backed securities (net interest margin; NIM). While that spread has been relatively stable historically, Exhibit V shows that it has fallen slightly over the last decade. I don’t have any special insight as to why, except “lower rates lead to compressed NIM”, but I would note that NIM expanded in fiscal 2021 despite lower rates and flat interest income. KMX attributes this to strong interest from securitization partners/investors. I’m under the impression that KMX has built a reputation for originating high quality receivables, which helps generate strong demand for their program; net credit losses (as % of receivables) peaked at 1.74% in 2008, but have generally been just 1.0%.

What’s great about KMX’s position as a lender is that they own the customer relationship, and basically get a right-of-first-refusal on a loan. They can choose to dial up or down how much risk they take, and I’m inclined to think that CAF will eventually take a greater share of total funding as KMX learns more about the risk profiles of Tier 2 and Tier 3 customers. I expect this to be a modest tailwind.

Lastly, CAF income is reported as NIM less provision for loan losses and direct CAF expenses, which is roughly 50/50 split between payroll and other. CAF employs more than 700 people today, but as the omni-channel picks up steam and more customers pursue a totally self-directed checkout (including financing), I suspect that CAF headcount per financed vehicle will fall and contribute to growth in CAF income. It’s worth reiterating that financing any vehicle, but used vehicles in particular, requires another set of negotiations at traditional auto retailers. KMX has always made this a seamless and no-haggle experience, and continues to do so on the omni-channel platform, which differentiates them relative to most competitors.

To summarize, their approach to first-party and third-party financing: reduces friction for buyers, which supports growth in retail unit sales; requires very little KMX capital, because they lean on non-recourse funding; and results in a significant and relatively stable complimentary cash flow stream. Most KMX competitors, even large ones, don’t have a first-party financing business, and this is one reason that KMX generates much higher ROIC than the peer group.

Other

KMX has two remaining revenue streams which they classify as extended protection plans (EPPs) and Other.

The EPP business generates revenue by selling extended service plans (ESPs; typically 60 months) and guaranteed asset protection (GAP) on behalf of third-party partners. KMX typically receives an upfront fee with some profit-sharing over the life of the contract, and has effectively nil associated expenses or future obligations. The attach rate for ESPs and GAPs was 60% and 20% in fiscal 2021, and that seems to have increased slightly over time. Exhibit W illustrates this by showing EPP revenue as a percentage of Retail revenue. Even though EPPs made up just 2.5% of revenue in fiscal 2021, I estimate that they contributed to roughly 17% of gross profit, and even more of operating income. It wasn’t immediately clear to me why KMX doesn’t internalize more of these services, specifically the ESPs, but when I looked at some of their partners like Fidelity Warranty Services, I found that they cover more than 13 mln contracts and have 6,000 participating service centers nationwide. This seems to be a service that requires scale to do well; they need to partner with lots of service centers, and cover a sufficiently broad pool of vehicles. Ten years ago, KMX probably wasn’t positioned to do that. Today, it might be possible. If KMX had covered 100% of ESPs over the last five years at similar attach rates, they’d be servicing 2.3 mln contracts. If they could effectively build a network of participating service centers, this might be an interesting way to grow the ESP business. Admittedly, I don’t know enough about the ESP space to have a strong view, and I wouldn’t include any expectations of that in a base case, but it’s an interesting angle to think about.

The remaining Other bucket is some combination of new-vehicle sales and services completed by KMX. This revenue stream has shrunk considerably on both a relative and absolute basis over the last 5, 10, and 15 years. Revenue fell from $600 mln in 2006 to just $200 mln in 2021, and part of the reason is that KMX has been divesting of new-vehicle franchises (including one in 4Q21). This is now a negligible part of the business.

New Opportunities

The management team at KMX is clearly looking at new ways to participate in the used-vehicle ecosystem, and started by buying a minority stake in Edmunds in fiscal 2020 for $50 mln. Following that investment, KMX and Edmunds tested the CarMax instant appraisal feature on the Edmunds website. That initial “test” worked quite well, and after working with Edmunds for more than a year (and getting a better behind-the-scenes look at the business), KMX decided to buy the entire business for an incremental $354 mln. That deal should close in June.

But what does Edmunds do? For more than 50 years, Edmunds has been one of the “most well established and trusted online guides for automotive information”. They test drive new vehicles, write reviews, publish insights on new and used vehicles and markets, and provide tips to consumers for buying and selling vehicles. More recently, they help consumers compare vehicle specifications, reviews, and prices online, and have built a search engine that displays new and used vehicle inventory from more than 25,000 dealers in the United States. As a trusted consumer resource, they receive more than 15 million unique monthly visitors to their site and mobile app. All of this is free for consumers, which is possible because Edmunds monetizes by selling technology products and advertising solutions to their dealership and OEM partners. As a private company, I can’t find any good financial information on Edmunds, but I can look to some public competitors like Cars.com to make some guesses. Cars.com generates $500-600 mln in revenue and normalized net income somewhere in the $25 mln range. After making a few adjustments, I estimate that Edmunds might generate $15-20 mln of net income/year, which would represent <2% of estimated KMX fiscal 2022 earnings, and a purchase price of 20-25x P/E.

On the surface, this hardly seems noteworthy, but I suspect there are some compelling long-term reasons behind the acquisition. With 15 million unique monthly visitors, Edmunds has a massive audience that KMX can tap to source more used vehicles directly from consumers. They’ve already integrated the KMX instant-appraisal feature into the Edmunds website, but I suspect awareness and penetration of this feature is still low. When I go to the Edmunds website, I see four tabs: New Car Pricing, Used Cars for Sale, Appraise My Car, and Car Reviews. It’s only when I go to the Appraise My Car tab, and scroll down, that I see “Sell Your Car - Get An Instant Cash Offer” in relatively small print. If I appraise my vehicle, I do get asked if I want to see an instant cash offer, but this is now many steps into the process. I’d also note that I can’t find any Edmunds advertisements bringing awareness to the instant cash offer feature. I would be surprised if KMX didn’t make the instant cash offer feature more obvious on the site and more seriously advertise this through national campaigns. Over time, organic growth in awareness is also sure to increase, and combined, I’d expect Edmunds to drive a significant increase in consumer-sourced vehicle purchases for KMX. This should simultaneously increase Retail GPU (or help them lower prices), and grow Wholesale unit sales.

As an independent site, the value of Edmunds to consumers comes from impartial research, reviews, and inventory search results, so I don’t think they’ll directly be able to favor KMX vehicles in search results. That said, it seems possible that KMX can leverage Edmunds data to feed their pricing algorithms to be more competitive. I’m not sure if there are restrictions to doing this, but it would create a huge advantage for KMX if there wasn’t.

Lastly, with 25,000+ dealership relationships, there might be other unique ways to leverage the Edmunds network. For example, what if KMX/Edmunds were able to create a program where dealerships can buy or sell wholesale inventory directly through KMX instead of going through a traditional Manheim or ADESA wholesale auction. The gross margin on wholesale auction fees is >80%, and if KMX split this fee 50/50 with third-party dealers it would be a win-win. Alternatively, maybe KMX can expand CAF to third-parties. I’m sure there are lots of possibilities here, some of which might not be feasible, and some of which I’m not even thinking about. Either way, I’m reasonably confident that KMX will leverage these B2B relationships in some way to drive incremental value for KMX shareholders.

Performance

I’ve already illustrated that historical operating performance has been quite impressive, with significant unit growth in a stagnant industry, and consistent gross profits per unit. Exhibit X shows that this has translated into a revenue and gross profit CAGR of 8-10% over the last ten and fifteen years. Net income growth of 12% would have been closer to 10% if not for the reduction in corporate taxes. I note that capital intensity for the business has generally fallen over time, which has allowed KMX to repurchase nearly 30% of their shares over the last decade, and contributed to EPS growth in the mid-teens range (would have been 12-13% without the reduction in corporate taxes).

This strong operating and financial performance has translated into the highest trailing 5-year ROE in the peer group (excl. CVNA, which is generating negative net income, for now). They’ve done this while simultaneously deploying significantly less leverage than the peer group.

That industry-leading ROE has also been increasing over time (as it has for most peers), partly as a function of modestly higher leverage, and partly as a function of higher asset turnover. Despite the negative impacts from COVID, KMX continues to generate returns substantially above their cost of capital.

Financial Position

KMX has historically utilized much less debt than competitors, even though leverage has increased slightly in recent years. Management targets a 35-45% adjusted-debt-to-capital ratio, which I estimate works out to something in the low-to-mid 1.0x D/EBITDA range. In my personal view, they could comfortably take that much higher; in the depths of the financial crisis, when operating income fell substantially, interest coverage was still >10x. In any event, despite low leverage, KMX has still been able to grow reasonably quickly and return significant cash to shareholders. Exhibit AA illustrates this by showing historical (and forecast) sources and uses of cash. I note that KMX has been relatively inactive on the M&A front, with Edmunds being a rare exception. Barring any significant acquisitions, KMX is likely in a position to accelerate share buybacks, even as they continue to grow the top-line at ~10%/year.

The non-recourse debt supporting CAF does exceed $13 bln and will likely double over the next decade. I’m not concerned about this, but it’s worth highlighting that KMX is very dependent on the securitization market, and if funding became harder to secure in that market it could either A) result in higher funding costs, or B) cause KMX to temporarily fund some of these auto loans with their own balance sheet. In addition, if third party financing partners were less willing to extend capital, it might also impact retail unit sales. I suspect that one reason KMX keeps a pretty lean balance sheet is to mitigate the risk of any temporary disruptions to any of their financing channels.

Management & Governance

Observation #1: Home grown executives and long tenure

The CEO, William Nash, joined KMX in 1997 when it was still a subsidiary of Circuit City. He held multiple roles before being promoted to CEO in 2016 (he’s still just 50 years old). What’s remarkable is how many top KMX executives joined in the 1990’s or early-2000’s: Thomas Reedy, an EVP and previously CFO, joined in 2003; Edwin Hill, the COO, joined in 1995; Diane Cafritze, the Chief HR Officer, joined in 2003; and Joseph Wilson, the SVP of Store Strategy and Logistics, joined in 1995. Most remaining executives joined prior to 2010. Even the current Chair of the Board, Thomas Folliard, who held the CEO role from 2006-2016, joined in 1993.

A small part of me worries that having too many life-long KMX executives will lead to group-think and stagnant thinking. Sometimes it’s good to get an injection of fresh perspectives from outsiders, particularly in an industry being disrupted by innovative companies like CVNA. That being said, lots of successful businesses like Constellation Software tend to have long-tenured executives promoted from within. When you’re the leader in a space, maybe you already have the best talent and a robust culture that promotes innovation. That seems to be the case here, particularly considering how quickly KMX has adopted technology and online sales relative to most competitors. There is also merit to having executives that have held more front-line and operational roles within the business, which makes the more attuned to the challenges and customer value proposition than an executive who has moved laterally from another industry. The long tenures are also likely a reflection that KMX is a great place to work. On balance, I think this is more positive than negative.

Observation #2: Great operators, average capital allocators

On occasion, I stumble across management teams that are simultaneously great operators and capital allocators. Those teams aggressively deploy capital on acquisitions and opportunistic buybacks, often flexing the balance sheet for “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunities. I’ve found no evidence of that here. Instead, my own view is that this management team falls into the great-operators-but-average-capital-allocators camp, which is fine considering how exceedingly rare it is to find managers who excel at both. To be clear, I don’t see any examples of capital being deployed below their cost of capital. Rather, a significant portion of total FCF is returned to shareholders through systematic buybacks. Ultimately, I don’t mind the conservative stance and judicious management of capital, but I also wouldn’t build in any massively accretive M&A or opportunistic buybacks into the base case.

Observation #3: KMX cares about their people and culture

“On April 8, 2020, in response to the COVID-19 crisis, we announced that Mr. Nash would forgo 50% of his base salary, our executive vice presidents, including Messrs. Reedy, Hill, Margolin, and Lyski, would forgo 30% of their bases salaries, and our senior vice presidents, including Mr. Mayor-Mora, would forgo 20% of their bases salaries, effective immediately and until further notice.“

The board of directors also unanimously agreed to forgo their cash retainer indefinitely. I’m not certain if other incentive compensation will be impacted, which is typically tied to base salary, but either way I thought this was a good indication of thoughtful leadership.

As it stands, KMX relies heavily on their associates to deliver a great customer experience, and associate morale is therefore quite important; they need people to be happy and buy-in to the KMX-way. As they’ve transitioned to more of an omni-channel approach, they’ve avoided layoffs in favor of attrition, and have actively worked on repositioning associates with additional training where possible. Every indication shows that they value and invest in their people. Through COVID they provided transition pay to furloughed employees, and opted to pay for both the associate and employee portion of medical plans. All of these little things help contribute to favorable employee reviews (Glassdoor, Comparably, etc.). KMX has also ranked as one of the best places to work in the United States for more than a decade (link). To sum it all up, I’ve found no cultural red flags.

Observation #4: Aligned with shareholders

Management and director compensation is mostly tied to long-term performance, with long-term equity incentives driving the majority of total compensation (60-70%) for named executives. Long-term equity incentives are a mix of options (75%) and PSUs (25%). The options vest in equal increments over four years, with a seven year expiry. The PSUs are tied to three incremental one-year performance targets determined at the beginning of each year and typically tied to EPS growth, but no shares are paid out until the PSUs vest on the three-year anniversary of the grant date. Admittedly, I would prefer if management compensation was actually tied to a combination of metrics, including ROIC.

The executives and directors of KMX beneficially owned 3.2 mln shares at the end of fiscal 2021, worth nearly $500 mln at the current share price. Roughly 80% of those beneficially owned shares are tied to incentives that have not yet vested, and won’t for many years. With the exception of Thomas Folliard, who sold half of his holdings upon retirement, the majority of historical vested equity-based compensation to top executives and directors has been retained, which I view as a good sign.

In addition to significant equity-linked compensation for senior management, ~20% of all KMX employees are paid some combination of equity and equity-linked awards (including cash-settled RSUs). Roughly 75% of total equity and equity-linked compensation in fiscal 2021 was awarded to the broader employee base, representing nearly 2.0 mln shares (worth roughly $30k per participating employee), and these vest over a multi-year period. On top of these equity incentives, all non-executive employees are eligible to participate in the Employee Share Purchase Plan, and can allocate 2-10% of their compensation to the ESPP (up to $10k) in a given year, and KMX will match 15% of the contribution. To-date, more than 5 million shares have been purchased (in the open market) through the ESPP. The combined equity awards and ESPP participation are likely to have resulted in significant employee ownership, which helps get everyone rowing in the same direction.

Valuation & Scenarios

Retail

The primary driver of the Retail segment, and coincidentally the other segments, is retail units sold. As KMX ramps up their store footprint (and therefore acres of capacity), they should sell more vehicles. I started by thinking about what store penetration might look like ten years from now, and Exhibit AB shows an ordinal rank of KMX store penetration per state for multiple historical periods and my 2031 base-case forecast. In short, I think KMX will simultaneously increase penetration in existing regions and expand into the remaining white space.

My 2031 forecast shows that total store count goes from 220 in fiscal 2021 to 350 in fiscal 2031, and that net store additions start at 10 in 2022 (in-line with guidance) and slowly ramp up over the decade. It’s important to note that KMX will disproportionately open non-production locations, so even though the store count increases by 60%, actual acres of capacity increase by just 50%.

As a greater portion of units get purchased through the online channel, I expect that more units will be sold per acre of capacity (consistent with management expectations), so I take units sold/acre up from 300 in fiscal 2020 to 380 by fiscal 2031. As a result, unit sales grow by 6.5%/year and roughly double by 2031.

I don’t expect industry-wide used-vehicle sales to change meaningfully over the next decade, so most of that growth comes from increased market share. Management is guiding to 5% penetration of their addressable market (0-10 year-old used-vehicle sales) by fiscal 2026, and my base case happens to be consistent with that guidance. This is clearly an acceleration of share gains, but is supported by a new full-service omni-channel experience, increase in advertising spend, and better utilization of data and technology to improve the customer experience and prices. By the end of my forecast period, KMX still has market share <7% in this category, and even though the industry is likely to have consolidated significantly, I still don’t expect the Top 10 competitors to have a total share of more than 15%.

I expect that KMX will share the vast majority of any productivity gains they achieve with customers by way of more competitive prices, which will support higher unit growth. As a result, I expect that GPU will remain more-or-less flat through the forecast period despite rising ASP. This translates into slightly lower gross margins.

In the base case, these assumptions lead to gross profit doubling by 2031 (from $1.8 bln in fiscal 2021 to $3.7 bln in fiscal 2031).

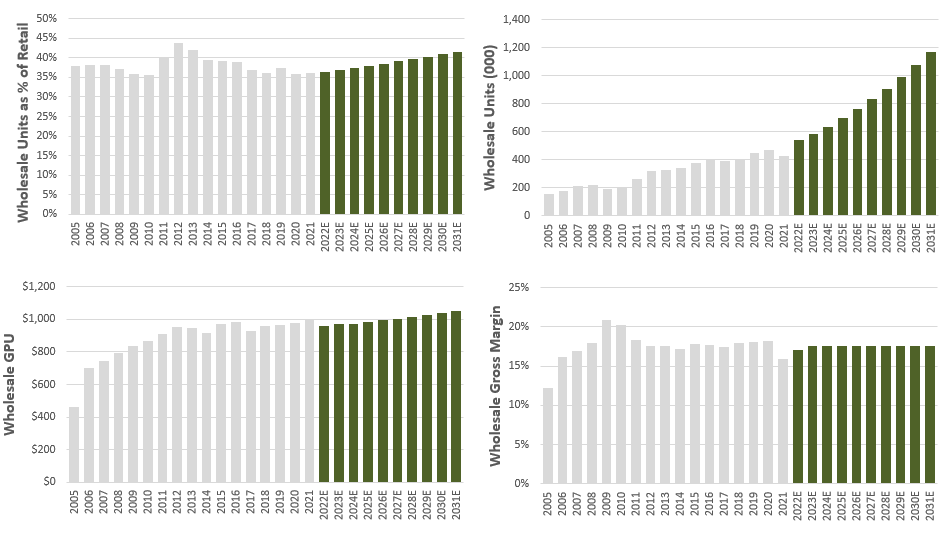

Wholesale

Wholesale volume is a direct function of retail volume, but I also think that wholesale unit growth will outpace retail unit growth as KMX purchases more vehicles directly from consumers and finds that they have more vehicles not fit for the retail channel; early data from the recently rolled out online instant appraisal offering supports this thesis. I therefore expect wholesale unit growth to be roughly 9%/year from fiscal 2020 to 2031, versus just 6.5% for retail unit growth. I expect that GPU and gross margins might be slightly lower in the near-term as ASP normalizes and more units get sold through online auctions. I also think that KMX will do more to offset this, and the recently announced pilot project that utilizes the KMX logistic network to transport vehicles for wholesale customers should support GPU in the future. Exhibit AG shows my Wholesale estimates in the base case, and this translates into gross profit growth of nearly 10%/year from fiscal 2020-2031.

CAF

CAF contributions are primarily a function of average managed receivables, net interest margins, net loan losses, and direct CAF expenses like payroll and technology. In the base case, I expect that managed receivables growth will follow growth in Retail revenue (units * ASP), while net interest margins will stay near all-time lows (high 5% range). I make a few small adjustments to account for CAF funding of more Tier 3 loans like slightly higher receivables growth, net loan losses, and net interest margins, but it doesn’t move the needle significantly in the model. I also assume that direct CAF payroll expense per financed vehicle falls slightly through the forecast period as more customers utilize the self-serve features on the online platform. All told, I have CAF contributions growing at 8%/year from fiscal 2020-2031.

Other

The majority of remaining gross profit comes from EPPs, and I expect EPP contributions to grow in-line with retail units sold. Net third-party financing expenses of $40-50 mln/year should become a wash with the recent changes in third-party fee agreements. The remaining new-vehicle and service contributions are likely to shrink the near-term and remain inconsequential long-term.

Margins

There are four big expense lines below gross profit: compensation and benefits, store occupancy, advertising, and other (which includes technology spend). As KMX sells more units online (a greater proportion of CEC associates and more units sold/acre) I expect that compensation and store occupancy expenses will proportionally fall. At the same time, I think a proportional increase in advertising and other expenses will offset some of this leverage. Combined, I expect the proportional decline in these expenses to more than offset any decrease in gross margins long-term.

Sources and Uses of Cash

As I already highlighted under Financial Position, KMX should generate substantially more cash flow than they can spend organically at attractive incremental returns. At the same time, they should be able to maintain a D/EBITDA ratio of 1.5x long-term versus 1.2x and 1.0x in fiscal 2020 and 2021 respectively (at the high end of their adjusted-debt-to-capital target range). I don’t include any accretive M&A in my base case, and therefore assume that 70% of available cash from operations and incremental debt will be distributed to shareholders through systematic buybacks (and perhaps eventually a dividend). If they repurchase shares at something close to my fair value estimate, on average, I estimate that KMX can reduce shares outstanding by another 30% over the next decade.

Tying it all together in the base case

I use 2020 as the reference point for historical and forecast growth rates to normalize for the transient impact of COVID. Exhibit AI shows that my base case assumptions drive annual top-line growth over the next decade of 8%, absolute net income growth of slightly higher than 8%, and EPS growth of nearly 12%. ROIC remains relatively consistent with historical returns, while ROE approaches 30% as D/EBITDA approaches 1.5x long-term and the company repurchase shares.

My base case suggests that fair value is $173/share, which is ~45% higher than the current price of $118/share. In other words, I expect that an investor today could earn a 12% annual return over the next decade. Exhibit AJ shows a screenshot of my DCF output tab.

Scenarios

My bear and bull case scenarios suggest fair value of $109/share and $238/share respectively, which works out to a 6% and 18% ten-year annual return from the current price. These scenarios are meant to represent what I view as the 10th and 90th percentile outcomes.

Conclusion