Philip Morris International (PM 0.00%↑) has roots going back to 1847 when Philip Morris opened his first tobacco shop in London. The business passed to Philip Morris’ son in the 1880’s before William Thomson took control in 1894. Thomson crossed the pond at the turn of the century, and in 1919 Philip Morris & Co. was incorporated in the United States. Philip Morris & Co. made a few unrelated investments and continued to expand their cigarette business internationally until 1985 when Philip Morris Companies was incorporated and became a publicly traded holding company (under the MO 0.00%↑ ticker). That publicly traded holding company had four subsidiaries: Philip Morris U.S.A., Philip Morris International, Miller Brewing, and Kraft Foods. Yes, you read that right – cigarettes, beer, and macaroni and cheese.

MO sold Miller Brewing to SAB in 2002, rebranded from Philip Morris Companies to Altria in 2003, and spun-out Kraft in 2007. For the briefest moment in time, Altria was left with a global tobacco business (Philip Morris U.S.A. and Philip Morris International), but then they spun out Philip Morris International in 2008 (I’ll refer to Philip Morris International as PMI for the rest of this piece).

Altria and PMI signed an Intellectual Property Agreement (IPA) where PMI owned all rights to jointly funded intellectual property (IP) outside the United States and Altria owned all rights to jointly funded IP inside the United States. In other words, Altria could only sell Marlboro in the United States, and PMI could sell Marlboro everywhere else. For IP independently developed between 2008-2018, each business would receive priority position to obtain those rights – if PMI created a new nicotine delivery system, Altria would be able to license it for use in the United States. After 2018, all independently developed IP would be free and clear.

With the spin-out transaction and IPA, PMI became the largest tobacco business in the world outside of the U.S. and China, with a cigarette market share (ex. U.S./China) of ~30%. In large part that was because they owned some of the oldest and most popular brands in the world like Marlboro, Chesterfield, Parliament, L&M, and Philip Morris. Despite their dominant position, PMI couldn’t fight the tide of declining global cigarette consumption, and net revenue from their cigarette business is now down 32% from the peak in 2012. With the cigarette industry in terminal decline, PMI started investing in new non-combustible tobacco and nicotine products. Collectively, these new products are included in the Smoke-Free Product (SFP) business segment. Exhibit A shows PMIs historical net revenue by segment (Combustibles is almost all cigarettes), and we can see that the SFP segment has grown significantly since PMI started introducing those products in 2015. Last year, the SFP segment was responsible for 31% of net revenue and PMI expects that it will generate ~50% of net revenue by 2025.

I don’t think there is any debate that smoking is bad for you. Cigarettes suck, society knows it, and over a long enough time horizon that Combustible business should go to zero. At the same time, I don’t necessarily think that nicotine in isolation is that horrible. It’s addictive, sure, but from all the research I’ve read it’s not a contributing factor to cancer, COPD, or many of the other health problems that cigarettes are so infamous for due to combustion and the thousands of chemicals present in a cigarette stick. What fascinates me most about PMI is that their SFP business should help accelerate the death of cigarettes – a core part of their strategy is to introduce compelling nicotine-delivery systems that incentivize existing smokers to switch from cigarettes. Considering there are 1.0 billion cigarette smokers in the world today (ex. China), that shift could have profound implications for public health. It could also have significant positive profitability implications for the legacy tobacco businesses that lead the charge. The best tobacco business will transform into nicotine businesses, and PMI is well on its way to making that transformation.

Death to Cigarettes

Exhibit B shows estimated global cigarette consumption since 1900 as measured by sticks (including the U.S. and China, where PMI doesn’t operate). Globally, cigarette unit sales peaked in 2012 and have declined ~17% since.

Even though global consumption peaked in 2012, consumption in a lot of western countries peaked decades ago, and that really started in the United States. The link between cigarettes and cancer started to show up in research in the 1940’s and 50’s. After reviewing thousands of these research articles, the Surgeon General of the U.S. Public Health Service released the first damning report on smoking in 1964, and that marked the top in U.S. cigarette consumption per capita. Consumption per capita then peaked in other western countries through the 1970’s and 80’s (Exhibit C). Even with population growth, the rapid decline in per capita consumption has been enough to cause a significant reduction in unit sales.

Given the decline in western consumption, the only reason that global consumption took until 2012 to peak is that unit sales elsewhere skyrocketed. China alone is responsible for nearly half of global cigarette consumption today, and cigarette consumption per capita is >3x higher than the United States. Similarly, cigarette consumption per capita in places like Indonesia is >2x higher than the United States and unit sales in Indonesia are unchanged from a decade ago. In absolute terms, total cigarette unit sales have even increased in some places like Turkey, where 28% more cigarettes were sold last year than in 2012. Despite some of these outliers, it does appear that most countries have now hit peak cigarette consumption (even Turkey), and as demand in places like China, Turkey, and Indonesia starts to roll over it should accelerate the decline in global consumption.

A lot of this decline comes down to better awareness, higher excise taxes (which I’ll get to in a second), and other public policy initiatives that deter smoking. What I find particularly interesting is that very few countries are resting on their laurels – new cigarette restrictions are still being introduced all the time. For example, late last year Mexico banned all smoking in public places, effectively relegating cigarette consumption to private residences. I’m not sure how firmly this will be enforced, but the new law is bound to have a meaningful impact on unit sales (Mexico represented ~5% of PMI’s cigarette sales in 2022). Similarly, New Zealand introduced a new law last year that makes it illegal for anyone born after January 1, 2009 to ever purchase cigarettes. Barring illicit purchases, that means there will be no new smokers picking up the habit. While Mexico and New Zealand are outliers today with these restrictive policies, I expect plenty of other countries will follow suit. In my view, it’s basically a foregone conclusion that cigarette unit sales in most of PMI’s markets will approach zero, it’s just a matter of when. The “when” question is really difficult to answer, but I’ve seen some estimates that suggest the death of cigarettes might occur by 2050.

What does that mean for PMI’s Combustible business?

Exhibit D shows PMI’s cigarette unit sales and Combustible net revenue from 2000-2022. The first thing I want to point out is that PMIs cigarette unit sales are down 33% from the peak while consumption is only down 17% globally. PMI has lost share in the cigarette market. A big reason for that is cannibalization from their new heat-not-burn products – adjusting for this, PMIs share of total stick consumption is roughly flat, but I’ll circle back to that dynamic later. The second thing to notice is that even though PMI is selling 10% fewer sticks today than they did in 2000, their net revenue is 59% higher today than in 2000. Said differently, net revenue per stick is 75% higher today. Higher prices have helped offset some of the decline in unit sales, and it’s worth exploring those pricing dynamics to better understand the range of outcomes for a Combustible business that’s otherwise in terminal decline.

The pricing dynamic in the cigarette business is interesting for a couple reasons. First, cigarette demand is inelastic – meaning that a 10% increase in price is met with less than 10% reduction in demand. Lower income groups are more sensitive to change in price, but the median estimate for price elasticity of demand across income groups and geographies seems to be about -0.6 (a 10% increase in price reduces demand by 6%). Second, and equally interesting, is that this industry is very concentrated. A handful of large competitors like PMI, British American Tobacco, Imperial Brands, and Japan Tobacco International dominate the global stage. Sure, there are plenty of small regional competitors that are often state-owned, but these four large competitors have ~70% share outside of the U.S. and China. Knowing all that, you’d assume that these businesses have decent pricing power and have exercised that power over time. Technically, you’d be right, but unfortunately for these businesses nearly 80% of the gross price increases since 2000 have been taxed away!

One of the biggest taxes that this industry faces is excise tax – an indirect tax paid by producers to governments, usually to promote a public policy objective. In the case of cigarettes, high excise taxes are meant to deter smoking. Even though price elasticity of demand for cigarettes is low, it’s not zero, and most of the research I’ve read suggests that high (and increasing) excise taxes are effective at reducing demand.

PMI reports two revenue numbers: gross revenue, which is what they sell cigarettes for to their end customer (retailers, distributors, or wholesalers); and net revenue, which is gross revenue less excise taxes they’re required to pay directly. When governments increase excise taxes, it’s up to PMI to flow through those tax increases via higher gross prices. If they didn’t, then net revenue per stick would fall.

Exhibit E shows PMIs historical net revenue/stick for the Combustible segment and gross revenue/stick including the excise tax. Gross revenue/stick is up 170% from 2000-2022 (4.6% CAGR), while net revenue/stick is up just 75% (2.6% CAGR) because excise taxes are up 270% (6.1% CAGR).

As an aside, PMI has technically increased net prices in local currency much faster than 2.6%/year (and therefore gross prices more than 4.6%/year). Exhibit F shows the cumulative drivers of net revenue growth since 2006, and we can see that FX has been a huge offsetting factor to price. Since most of PMI’s revenue is not US$-denominated and many of their local currencies have depreciated, the net US$ price increases/stick I’ve shown above are much lower than local currency price increases/stick. Even still, I think the appropriate way to think about pricing power would be to include the FX drag.

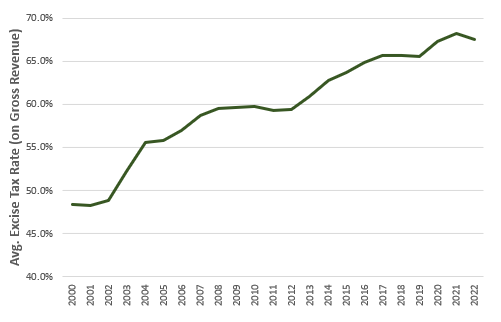

In any event, Exhibit G shows the implied average excise tax rate (on gross revenue) for PMI’s Combustible business since 2000, and it’s hard to overstate how big of an impact this has had on net revenue. For example, when Saudi Arabia introduced an excise tax in 2017, retail prices of cigarettes roughly doubled as PMI passed that tax through via higher gross prices, and unit volume experienced a y/y decline of 36%! Colombia experienced something similar in 2016 (tax rates tripled and unit sales fell 34% two years later), and Pakistan experienced something similar earlier this year (taxes more than doubled and unit sales fell 30%). In each instance, even though gross price increased a lot more than demand fell, the net impact to PMI (net revenue * units) was negative. If excise tax rates stopped increasing, PMI could probably increase their net revenue per stick faster than unit volumes decline (for a long time), but I don’t think excise taxes are taking a breather here. For example, Indonesia is hiking excise taxes by 20% from 2022-2024, and that market represents 14% of PMIs total cigarette unit sales (probably mid-single digit share of Combustible revenue). Similarly, it looks like the EU might update its Tobacco Tax Directive which would increase the minimum tax on tobacco products in the region. Even without an update to the Tobacco Tax Directive, plenty of European countries are continuing to hike taxes in 2023+, and the EU is responsible for roughly a third of PMI’s Combustible net revenue. For example, Poland plans to increase the excise tax on cigarettes by 10% every year through 2027.

In my view, it’s reasonable to expect that PMI could increase gross prices on cigarettes in-line or slightly ahead of inflation until the cigarette business dies, but I also think it’s true that excise tax rates will continue to increase for a long time. As a result, I loosely hold the view that PMI will only be able to increase net prices on cigarettes (including any FX drag) by 1-2%/year. If unit volumes declined at 7-8%/year (assuming cigarette sales are down 90% from peak by 2050), then we should expect that net revenue for the Combustible segment should decline by something like 6%/year. That would be an acceleration relative to the last decade where net revenue fell by just 3.7%/year for the Combustible business.

Despite being in terminal decline, the Combustible segment is still a remarkably profitable business with operating margins consistently >35% and ROIC in the 30-40% range. I’ve shown PMI’s total margins and ROIC in Exhibit H because I can’t isolate each metric for each segment, but I’d note that neither margin nor ROIC seem to have deteriorated meaningfully since the Combustible business peaked in 2012 (the drag on ROIC from 2012-2014 was FX-related). Note that the SFP business only started moving the needle in 2017/18. In my view, the death of cigarettes is manageable from a business perspective because it’s slow and predictable. PMI has time to rationalize manufacturing facilities and headcount at a measured pace without having to make massive adjustments in any one year. So long as the decline in cigarette unit volume remains stable, I suspect PMI will continue to generate strong margins and ROIC from this business. It’s also worth mentioning that PMI can repurpose some of their manufacturing facilities to produce SFP products, which helps prevent ROIC dilution.

All told, I think the Combustible business is economically fantastic, but bad for the world, and it’s a good thing that it’s in terminal decline. I don’t think this is a business that would be easy for PMI to sell, nor would they want to. On the path to zero, I think it’s pretty clear that this will be a cash cow – it will require very little investment to maintain and spit out significant free cash flow while PMI transitions to a smoke-free future.

Smoke Free Products

PMI’s SFP business is what really got me interested in writing this deep dive. Technically this segment includes all e-cigarettes/vaping, snus, moist snuff, nicotine pouches, and heat-not-burn products, but the two needle-moving categories for PMI are heat-not-burn and nicotine pouches which collectively account for nearly 90% of segment net revenue following the Swedish Match acquisition.

PMI’s heat-not-burn portfolio revolves around the IQOS device, which they started working on around the time that cigarette unit sales peaked. With IQOS, a heated tobacco unit (HTU) is inserted into the device and heated at <50% the temperature of a cigarette, which avoids combustion and instead produces a nicotine-infused aerosol. These HTUs look similar to cigarettes, and the sticks are also purchased in packs. According to PMI, the IQOS aerosol generates 90-95% fewer toxic substances than cigarette smoke, although the independent studies I’ve reviewed suggest that the range is more like 80-90% depending on the substance. In any event, heat-not-burn technology is now widely accepted as being meaningfully better for health than conventional smoking. Multiple regulatory agencies have also confirmed that HTUs are vastly preferred to cigarettes. For example, the FDA authorized certain version of IQOS as Modified Risk Tobacco Products (MRTPs), and allows PMI to market IQOS with the following claim:

“Scientific studies have shown that switching completely from conventional cigarettes to the IQOS system significantly reduces your body’s exposure to harmful or potentially harmful chemicals.”

No doubt heat-not-burn consumption still has negative health implications, but for the ~1.0bn smokers around the world (ex. China), the value proposition of switching from cigarettes to HTUs is compelling. That’s particularly true considering the successful smoking cessation rate is <10%.

PMI’s heat-not-burn strategy revolves around converting existing legal-age smokers, and they’ve had significant success doing so since the pilot launch of IQOS in 2014 – part of the reason is that HTUs (vs. other SFP) most closely resemble conventional smoking, so clearly has broader appeal to smokers than oral nicotine or vapes.

You can think about this business as A) an upfront device sale that generates effectively no operating profit, and B) recurring HTU stick sales, where a single HTU stick is functionally comparable to a single cigarette. Exhibit I shows SFP segment net revenue since IQOS was launched, and we can see that HTU sales make up the bulk of total segment revenue. In my view, IQOS is the most important part of the PMI story today, so I’ll walk through the opportunity in more detail shortly.

In addition to IQOS, PMI acquired Swedish Match last year, which would have represented 19% of segment revenue had PMI owned this business for the full year. While Swedish Match dabbles in cigars, chewing tobacco, moist snuff, and snus, the most important part of this business is nicotine pouches – in particular, ZYN, which is the fastest growing brand within Swedish Match and approaching 50% of net revenue as of 2Q23. Next to IQOS, Swedish Match is probably the second most important part of the story, so I’ll also come back to this in more detail later.

Rounding out the SFP segment are some inconsequential vape products and the Wellness and Healthcare business. In my view, the Wellness and Healthcare business is unlikely to ever be material to PMI, but it probably has some option value. I’ll cover this after a deeper dive on IQOS and Swedish Match.

IQOS

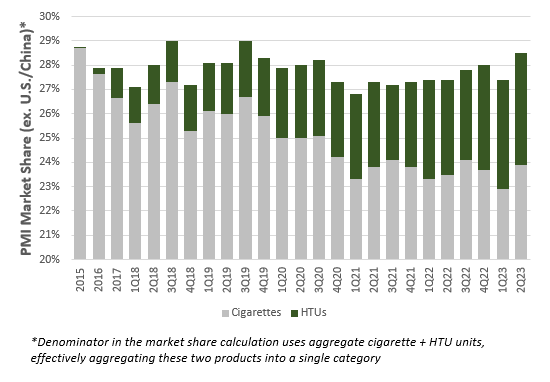

PMI launched an IQOS pilot in Japan in 2014, and they’ve since expanded into nearly 80 markets. By comparison, PMI’s cigarettes are sold in 175 markets, so at the highest level it’s fair to say that this journey is far from over. PMI’s cigarettes skew toward the premium end of the spectrum with brands like Marlboro. IQOS and the related heat sticks are also premium products in the heat-not-burn category, so in the markets where IQOS is currently available you’d assume that IQOS HTU sales cannibalize some of PMIs cigarette volume. Exhibit J shows PMIs global share (ex. U.S./China) of combined cigarette and HTU unit sales, and the data does suggest that PMI’s HTU unit sales are indeed cannibalizing PMI’s premium branded cigarette sales – in other words, total share has remained relatively flat since 2015, and PMI is just substituting their HTUs for their cigarettes. It looks like 1Q21 could have been an inflection point, with combined share eking higher every quarter since, but I’ll come back to that.

Since the entire industry is in terminal decline, and PMI’s combined share is ~flat, it’s no surprise that PMI’s aggregate cigarette and HTU unit sales are down 14% from 2015-2022. Despite that unit decline, net revenue from cigarettes and HTUs (ignoring the other SFP stuff) is actually up 13% over the same period (Exhibit K)! While part of that 27% delta is explained by cumulative cigarette price inflation in US$ terms of 9.5%, the primary reason that net revenue performed so much better than unit sales is that HTU net revenue/stick is substantially higher than cigarette net revenue/stick.

To be clear, the retail price of HTUs is fairly similar to the retail price of comparable cigarettes. The reason that HTU revenue/stick is so much higher is because of a difference in excise tax rates. Exhibit L breaks down the subcomponents of the retail price in international dollars for cigarettes and HTUs using data from the WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021 (sample size is 31 countries that account for >50% of ex-China consumption). We can see that excise tax rates for HTUs are a fraction of what they are for cigarettes, and that the net revenue per stick is therefore 2.3x higher for HTUs than cigarettes. PMI says that their net revenue per stick is 2.5x higher for HTUs than cigarettes, which is probably attributable to a slightly different geography/pricing split than the WHO sample, but either way the message is clear: HTUs are substantially more profitable than cigarettes. To take it one step further, PMI says that the gross margin on HTUs is 10% higher than cigarettes, so the gross profit per unit is 2.9x better on HTUs. To put that into context, if all of PMI’s 2022 cigarette volumes had instead been HTUs, PMI’s EPS would have been ~$18.00/share vs. the $5.83/share that they reported.

The obvious follow-up question should be:

“Why are HTU excise taxes so much lower than cigarettes, and is that a sustainable spread?”

At this point I think it’s widely accepted that a lot of these new smoke-free products should be placed in the “harm reduction” category. Because we know that price does impact demand to some degree, it seems that many policy makers have taken the stance that reduced-risk products should be taxed less than cigarettes. To take it one step further, some of the policy recommendations I’ve read suggest that there should be a sliding scale of tax rates – on that sliding scale, HTUs would be taxed less than cigarettes, but other categories deemed less risky than HTUs (like nicotine pouches or some vapes) would be taxed even less than HTUs.

In theory, I suppose that’s good policy, but because PMI and other competitors are generally free to set prices at whatever they want, it doesn’t appear that the retail price of HTUs is materially cheaper than cigarettes – there isn’t currently a big price incentive for consumers to switch. All that’s really happened is that HTU manufacturers are making a killing. I suppose you could argue that policy makers would be fine with that for some interim period where cigarettes still represent the majority of nicotine consumption. They should want to incentivize smoke-free innovation and then incentivize these businesses to push conversion. But if we fast forward to a world where HTUs represented 80% of combined cigarette + HTU unit sales, I’d be shocked if excise tax rates for HTUs remained this low.

Personally, I expect that HTU excise tax rates eventually approach cigarette excise tax rates, and because retail selling prices are already comparable to cigarettes, I don’t think PMI will be able to pass through most of that tax increase to end consumers. As a result, I think net revenue per HTU stick could fall significantly. We’ve already seen some isolated instances where this is playing out, like Germany, which changed excise taxes on HTUs in 2022 such that they would come in at 80% of the comparable tax for cigarettes. That closes the excise tax spread considerably, and PMI has not been able to pass through that higher tax via gross price increases, resulting in declining net revenue/stick. The same goes for Japan, which increased the HTU excise tax rate from about 50% of the cigarette rate in 2017 to 75% in 2020, and just increased it again to be about 85% starting in October 2022. Germany and Japan appear to be outliers, and PMI is challenging some of these changes in court. Nevertheless, it appears incredibly likely that the excise tax spread narrows over time, even if that takes a while to play out globally. In the meantime, PMI is likely to enjoy a significant economic benefit from conversion, and even as the spread narrows, HTUs should remain significantly more profitable than cigarettes.

If I’m right that the excise tax spreads will narrow, but take a long time to do so, then the big remaining question becomes how many HTU units can PMI sell? To better understand where the puck is going, I think it’s helpful to look at where it’s been – Exhibit M shows HTU unit sales by geography.

Despite being active in nearly 80 markets today, 6 countries still represent more than 66% of PMI’s HTU unit sales (vs just 24% of cigarette unit sales). Part of the reason is that 20% of their HTU markets are <2 years old, and ~50% are <4 years old. In Exhibit N I’ve show PMI’s HTU share (as a % of total cigarette + HTU volume) at 2, 4, and 6 years after launching in the core markets I highlighted above. Except for South Korea, which has some unique dynamics at play, PMI’s HTU share jumped significantly every two years after launch.

What I find particularly interesting is that in some of these markets, it looks like HTU sales initially cannibalized PMI’s cigarette sales, but as the HTU markets grew, PMI’s combined HTU + cigarette share started to increase. I’ve shown this dynamic for Italy and Germany in Exhibit O. Two years after IQOS launched, combined share was roughly unchanged for both countries. Four years in, and share was still unchanged in Italy and up only modestly in Germany. Six years in, and it’s clear that PMI is now taking combined share in both places. The reason for this is simple: PMI has ~25% share of the cigarette market, but 70-75% share in the HTU market. So, while PMI might cannibalize part of their cigarette business, at some level of penetration they start stealing share from other cigarette manufacturers. I think that helps explain why combined share from Exhibit J reached an inflection in early-2021 and has climbed consistently since.

Based on some of the data I’ve seen for other countries and cities, I have no reason to expect that IQOS shouldn’t achieve similar success in PMI’s newer markets as they mature, or in markets that they have yet to enter. Exhibit P shows that HTU share across 24 large cities where IQOS is already present was up on average 2.17% y/y through 2Q23. It’s also worth highlighting that momentum in the core markets mentioned above continues to be quite positive. For example, 2Q23 Japan HTU share was up 3.4% y/y. And, you have places like Rome that went from 23% share in 2Q22 to 28.6% share in 2Q23, while Italy as a whole was just 14.6% last year – PMI indicates that major cities are earlier adopters and should be leading indicators for the rest of the country, so this metro-level data bodes well for broader adoption.

It's worth reiterating that the multiple IQOS devices and compatible HTUs that exist today are largely premium products, which makes it difficult to achieve traction in lower-income groups who would essentially be trading up. To better reach the full spectrum of consumers, PMI released BONDS by IQOS and the BLENDS heat sticks late last year. They have pilot-city launches in the Philippines and Colombia, and while we don’t have hard data on how that’s progressing, PMI has now indicated three times that the pilots “continue to progress well”, and they plan to roll out BONDS to more markets in 2024. I suspect that net revenue/stick will be substantially lower than other IQOS HTUs, but still much higher than cigarettes in those markets. The other compelling dynamic with BONDS is that PMI’s cigarette business is over-indexed to the premium segment and under-indexed to cheaper segments, which means that the BLENDS HTUs are less likely to cannibalize PMI’s existing cigarette business. Some of the other major markets that PMI is planning to go after with this new iteration of IQOS include Egypt, Mexico, Brazil, Pakistan, Vietnam, and Indonesia – collectively these markets are responsible for ~25% of global cigarette consumption ex. China, so the opportunity for BONDS is massive. PMI specifically highlights that in these “emerging countries”:

“consumers will be moving from local brands [not owned by PMI], medium minimum positioning, to our heat-not-burn technology”

In addition to all the markets that PMI currently does cigarette business in, I think it’s important to highlight the upcoming U.S. opportunity. Recall that Altria and PMI signed an IPA in 2008 that defined the sandbox that each party could compete in. When PMI started developing IQOS they established a framework with Altria to commercialize IQOS in the U.S. Fast forward to 2019, and Altria started commercializing IQOS in the U.S. with exclusive distribution rights through 2029 (dependent on certain milestones). Some patent issues cropped up and British American Tobacco filed a complaint against Altria with the International Trade Commission (ITC). In 2021, the ITC effectively prohibited PMI from exporting IQOS to Altria for distribution in the U.S. In 4Q22, PMI reached an agreement with Altria to end their commercial agreement, which gave PMI the full rights to commercialize IQOS on their own. PMI had to fork over $2.7bn to Altria for that to happen, but now they control their own destiny and can start tapping U.S. consumers.

PMI is currently preparing to launch IQOS in the U.S. during 2Q24, which involves some infrastructure investments and a ramp in hiring. Based on the market share trajectory they’ve seen in existing IQOS markets, they’ve guided to 10% IQOS HTU share by 2030. If they hit that target, I estimate that the U.S. IQOS business could add $2-4bn of net revenue. For a business that did nearly $32bn in net revenue last year, this certainly isn’t a home run. At the same time, IQOS won’t be cannibalizing an existing cigarette business in the U.S., so the incremental revenue goes a long way at offsetting their declining Combustible business (U.S. IQOS sales could replace 10-20% of PMIs 2022 Combustible net revenue at 10% penetration by 2030). I also think it’s possible that IQOS market share in the U.S. could eventually exceed 10% – seven years after launch, Japan and Italy were at 23.6% and 14.6% respectively, and show no signs of slowing down. Admittedly, those are some of the more successful IQOS markets, and seven years after launch Germany is still at just 4.8% HTU share. Even still, markets like Germany are continuing to experience share gains, so I think the story there is far from over.

I think it’s established that HTUs are orders of magnitude more profitable than cigarettes and should remain that way for a long time even if excise tax rate spreads narrow. It’s also clear that while PMI has cannibalized some of their existing cigarette sales to-date, they’re taking a number of steps to take share in the combined category. BONDS is a big step in that direction. The U.S. opportunity is all gravy. But perhaps most importantly, PMI has a much higher share in the heat-not-burn category than cigarettes, which should drive share accretion over time if they remain the dominant player in the heat-not-burn space. That’s a big “if”, and the final thing I want to touch on is the IQOS competitive position.

Given PMIs share in the heat-not-burn category (~75%), it’s clear that they are a leader in the space. In my view, a lot of that comes down to being the first to seriously commercialize a heat-not-burn product. There were plenty of hurdles that PMI had to clear to do that, specifically on the regulatory front. Every country has their own process, but I think the U.S. is a good example to use.

In the U.S., PMI had to file a Premarket Tobacco Product Application (PMTA) for IQOS with the FDA, which they did in 1Q17. The PMTA process has multiple phases, and it took slightly more than two years for the FDA to authorize IQOS for sale in the United States. PMI also filed a Modified Risk Tobacco Product (MRTP) application in 2016, which would allow PMI to market IQOS as a modified risk tobacco product. It wasn’t until 2020 that the FDA approved that MRTP application. So, call it two years for the PMTA and four years for the MRTP. Moving through this process is a significant regulatory barrier to new competition.

To-date, the FDA has awarded a Marketing Granted Order (MGO, which is a successful PMTA application) for 45 discrete products from just 6 companies. Swedish Match and PMI are responsible for 16 of those MGOs. Of the remaining 29 MGOs, 27 were for vaping or oral products, and just 2 were for a competing heat-not-burn product by a small competitor. It’s also worth highlighting that in the last two years, 277 PMTAs from 268 different companies have been issued a Marketing Denial Order (MDO, which means the PMTA was unsuccessful). On the MRTP front, there have only been 16 successful applications, and 13 of those were received by Swedish Match and PMI. Normally, I think about regulatory hurdles as inconsequential, but in this case it’s clearly a big deal. Companies like PMI that had been working on products for years prior to PMTA or MRTP applications, and working to provide data on the health consequences of those products, clearly have a leg up on the competition. I’m sure more competing products will successfully move through the regulatory process, but it wouldn’t surprise me if PMI ends up with a 10+ year head start on serious competition.

Getting through that regulatory process first – wherever it is – goes a long way at building a recognizable brand in this new category. IQOS initially leveraged the Marlboro brand by producing Marlboro Heatsticks – I suspect this helped with converting some of their Combustible customers to HTUs. They’ve since set out to create new HTU brands separate from Marlboro, and these independent brands are gaining traction. What’s fascinating about this space is that it is so hard to market tobacco products to consumers. There are a million restrictions, and rightfully so. You can’t just spend a gazillion dollars on Instagram, Facebook, Google search, and traditional marketing to steal share. As consumers become more familiar with the various IQOS HTU brands, I think it will become increasingly difficult for competitors to steal those customers back from PMI. IQOS could perpetually have dominant share in this category, similar to how some of PMI’s cigarette brands have dominated in that category for 100 years. I don’t think dominant share means they’ll retain 75%, but could it be 40%? Absolutely.

Another benefit from being a first mover is that you can iterate on your product as you receive consumer feedback - by the time competitors launch V1, PMI will be on V5. Since launching IQOS in 2014, PMI has created multiple iterations of the device, each better (or different) from the one before. The latest iteration is called ILUMA, which doesn’t leave tobacco residue in the device and therefore requires no cleaning (unlike the original IQOS devices). According to PMI, ILUMA net promoter scores are notably higher than the earlier iterations of IQOS, and as they’ve rolled it out to existing IQOS markets there has been a significant uptick in adoption/HTU unit sales. I want to highlight that since PMIs cigarette business rolled over in 2012, they’ve spent more than $5.0bn on R&D, with the vast majority going toward new smoke-free products like IQOS. So not only are they one of the first to market, but they most likely have better products (higher quality, more variety) than some of the other early but small competitors like 22nd Century Group that don’t have $5bn to spend on R&D.

The final point I want to make on competitive position is that the large incumbent cigarette businesses are incredibly well positioned to scale an HTU business. The HTU and cigarette manufacturing processes are similar enough that PMI has been able to convert some of their existing cigarette manufacturing capacity to produce HTUs. That means they can quickly ramp up to billions of units/year without also spending billions of dollars in growth capex. By comparison, even if a small new entrant received regulatory approval and had a compelling product, it would take a very long time to ramp up production capacity to compete with IQOS in multiple markets.

All told, I think it’s clear that PMI has a significant head start in the heat-not-burn category. The barriers to entry and scale are high, and IQOS HTU brands are very well positioned to retain significant share even as new competition enters the space. The value proposition of HTUs for existing cigarette smokers is compelling, and I see no reason why mass conversion wouldn’t happen. There are <30mn IQOS users today, in a market (ex. China) with 1.0bn smokers, so the runway for IQOS unit growth appears very long. Sure, excise tax spreads probably narrow in the future, but I think that will take a long time to play out. In the meantime, PMI should enjoy extraordinary unit economics in this space.

Swedish Match

Since Swedish Match was a public company prior to the PMI acquisition, we have pretty good historical data on this business. Exhibit Q shows their net revenue (in SEK) broken out by segment. I had to estimate the ZYN contribution, but the margin of error should be relatively small.

The first thing I want to flag is that this business is growing at 4-5%/year excluding ZYN, thanks in large part to a robust cigar segment. That’s not bad, but by itself it wouldn’t justify the ~16x T12M EV/EBIT acquisition price that PMI paid for Swedish Match. And that’s where ZYN steps in.

ZYN is an oral nicotine pouch that uses pharmaceutical grade nicotine and contains no tobacco. That’s important because a lot of the health concerns with cigarettes, HTUs, and chewing tobacco are specifically tied to tobacco exposure. The ingredient list for nicotine pouches is relatively narrow – aside from nicotine it contains food-grade additives, flavorings, cellulose fibers, and a small handful of other things. Based on the minimal research I’ve seen on nicotine pouches it appears that they are the best reduced-risk nicotine product in the market (maybe second to nicotine quitting aids like gum). That’s not to say they are risk free (there isn’t enough research on this yet), but I suspect the health risk is 99% lower than cigarettes and still significantly lower than HTUs or vapes. That’s a compelling product to have in the PMI arsenal.

ZYN was launched in 2016 and has quickly become the most important brand in the Swedish Match portfolio, representing more than a third of 2022 revenue. Most of this growth came from success in the U.S., which represents something like 90% of total ZYN sales. Exhibit R shows ZYN U.S. unit sales per quarter since 2017, and the acceleration in unit sales in the two quarters following the PMI acquisition. Based on 2Q23 run-rate unit sales, I estimate that ZYN is currently a $1.0bn/year business in the U.S. alone. According to PMI, ZYN has ~68% unit share of nicotine pouches in the U.S., and 77% share by value. Needless to say, this is an incredible business.

I find it interesting that ZYN unit sales accelerated meaningfully since PMI acquired Swedish Match in 4Q22. It might be coincidence, but PMI did indicate that they are investing to expand the U.S. sales force and improve distribution (more distribution points). Awareness of the category is also improving (hell, I only heard about ZYN 6 months ago). Despite this early success, the nicotine pouch category is still a small fraction of the total U.S. nicotine market – something like 1% of industry revenue today. I’m personally of the view that the nicotine pouch category will be much larger in 10 years than it is today, but I have no idea if that will be 3% or 10% share. It feels like the range of outcomes here is large, but it wouldn’t surprise me at all if U.S. ZYN unit sales were 2-3x higher in 10 years than they are today, even if they lose share in the category to new entrants.

The other attractive component of the ZYN story is that Swedish Match had done very little to grow this business outside of Scandinavia and the United States. In fact, they just began launching ZYN in other European markets two years ago. PMI specifically calls out international ZYN expansion as a key medium-term opportunity and plans to start pursuing some of these launches in 2024. It’s not clear if ZYN will have the same success in other markets as it has enjoyed in the U.S., but it’s worth highlighting that the U.S. is just 6-7% of global (ex. China) cigarette unit consumption. If ZYN is already a $1.0bn/year business in the U.S., it really doesn’t require a lot of international success to see another $1-2bn in international nicotine pouch sales. Again, the range of outcomes here seems really wide, but it’s my view that the right tail of positive outcomes is very long.

In aggregate, Swedish Match put up 41% operating margins in 2022, but their Smokefree segment did a whopping 49%! I suspect that U.S. ZYN operating margins skew even higher than the average within Smokefree (call it low 50% range). By comparison, T5Y average operating margins at PMI were just shy of 40%. So, in addition to top line growth, as ZYN scales – and it’s clearly growing faster than the business overall – it should drive margin expansion.

Combined, IQOS and ZYN would have represented 36% of PMIs total net revenue in 2022 had Swedish Match been part of PMI for the full year, and probably closer to 41-42% of operating income. These are important drivers of growth for PMI, and I think it’s reasonably likely that growth from these two businesses will more than offset declining revenue and operating income from the Combustible business over the next decade.

Wellness & Healthcare

There is one final subsegment within SFP I want to address, and that’s Wellness & Healthcare. This is basically PMI’s foray outside of nicotine and tobacco. They kicked off this initiative with the acquisition of Fertin Pharma, Vectura Group, and OtiTopic in 2021, which have all been amalgamated into the Wellness & Healthcare segment. Collectively, PMI paid a little more than $2.2bn for businesses that would generate just $271mn in revenue and a $258mn operating loss in 2022.

So, what did PMI pay $2.2bn for? Here is how PMI defines these businesses:

Fertin Pharma: “a developer and manufacturer of pharmaceutical and well-being products based on oral and intra-oral delivery systems”

Vectura: “an inhaled therapeutics company”

OtiTopic: “a respiratory drug development company with a late-stage dry powder inhalation aspirin treatment for acute myocardial infarction”

As I understand it, these are businesses that help develop and manufacture delivery systems – from compressed gum, lozenges, and pouch powder at Fertin, to inhalers and nebulisers at Vectura. Fertin specifically makes pouch powder for nicotine pouches and extruded gum for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Vectura worked with Novartis to formulate a new inhaler for COPD treatment (a condition that impacts smokers), and they worked with Bayer to formulate and develop a nebuliser for treating pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clearly these are adjacent categories to PMI’s oral and inhaled nicotine products.

The strategic rationale seemed to be that PMI could marry some of their expertise with oral and inhalation delivery (they’ve spent billions of dollars on R&D here) with the expertise from these acquired businesses to help deliver new innovative products. The big example they gave of how they’ll leverage this combined expertise was the development of a new aspirin inhalation product. Apparently, when you consume aspirin orally it can take 20 minutes to kick in, but when inhaled it can hit your system in 30 seconds, and that speed is important in certain use cases – like treating heart attacks. Unfortunately, PMI just completed their first clinic trial for that particular product, and it was broadly unsuccessful. That setback, combined with a few other challenges, resulted in a $680mn impairment in the Wellness & Healthcare segment – roughly equivalent to 30% of what they paid for these businesses.

PMI initially guided to $1.0bn of revenue from Wellness & Healthcare by 2025, and those ambitions were walked down on the last conference call. They still plan to invest in new products, including the aspirin inhalation device, but at this point there is no real line of sight to this business becoming a positive contributor to operating income.

On the one hand, a lot of shareholder capital is being deployed into science experiments that might not yield a return on capital, let alone a return of capital. On the other hand, they’ve been explicit about not going ahead and “investing billions in a new molecule”, but rather “taking existing molecules and saying, how can I bring this molecule into an inhalable device that’s normally taken orally”. With that approach, the burn rate should be small relative to PMIs total FCF, and getting something right in these non-nicotine categories could have significant financial upside and help diversify this business away from what is generally perceived to be a declining industry. I wouldn’t personally pay for any upside here, but I can appreciate that this does have some option value, and it’s probably something to watch closely.

Unique Challenges

Despite a challenged Combustible business, I think there is a lot of positive momentum with IQOS and ZYN that has the potential to drive net revenue growth and modest margin expansion over the next decade. But it’s not all sunshine and rainbows. PMI faces numerous unique challenges that I haven’t got to yet, and some of these are hard handicap. I’ll do my best to go over them here.

Russia Exposure

Russia accounted for 9% of PMI’s combined cigarette + HTU volume and roughly 7% of net revenue in 2022, which is down only marginally from the year prior. PMI has continued to operate that business despite the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, and it’s not clear to me how much value to place on that Russia operation. Is the cash there stranded? Do the assets get expropriated? Do new sanctions impair PMI’s ability to operate it?

PMI has been trying to sell the Russia business, but it appears that Russia has created some barriers that might make divestment impossible. For example, a Russian Presidential Decree put in place last year gives Russia the power to block transactions outright – something that seems entirely likely to happen if PMI did try to sell those assets. Then there is the issue of finding a buyer that would even want to purchase that business. Either way, it seems incredibly unlikely that PMI will succeed with a sale process.

Now what? Is PMI even getting cash out of Russia from this business? Admittedly, it’s not that clear. In Exhibit S I show the reported asset value breakdown in US$, where I add back the FX translation loss to get a clearer picture of what’s happening if exchange rates hadn’t fluctuated. Marks at the end of 1Q22 look odd, but it’s pretty clear that the value of PMI’s assets in Russia have increased almost linearly. In fact, if we take the change in adjusted asset value over the last year (2Q22 to 2Q23), PMIs assets have increased by $717mn. If Russia is responsible for ~7% of net revenue, and operating margins on that revenue were comparable to the total business, that’s almost exactly how much FCF PMI would have generated during that period. I haven’t actually seen any official references to this, but it looks an awful lot like all the cash from this business is trapped in Russia – that’s particularly true considering they’d have no reason to hold that much cash in local currency otherwise.

In my view, it’s probably prudent for investors not to pay for this part of the business. I’d write down the current carrying value in US$ terms to zero and exclude what’s likely to be $800+mn in annual operating income from their reported figures. If this story has a happy ending, that’s gravy, but I certainly wouldn’t pay a lot for Russia today.

Lawsuits

The first tobacco-related litigation was filed against PMI in 1995 and they’ve since dealt with hundreds of cases. In total, 532 cases have been terminated in PMIs favor, 10 were initially in favor of plaintiffs but ultimately resolved in PMIs favor, and 5 cases were successfully decided in the plaintiffs’ favor but are subject to appeal. History would suggest that the success rate of litigation is low.

Nevertheless, there are still 82 pending cases against PMI as of 2Q23. Of those 82 cases, 19 are pending in Canada (including two going through the appeal process), and it looks like the consequences are significant. Two cases that were first filed in 1998 are particularly important. After nearly two decades in court, those cases were finally ruled in the plaintiffs favor in 2015. They then went to the Court of Appeal, which modified the damages in 2019 but largely affirmed the initial ruling. In total, PMI’s Canadian subsidiary (RBH) and the other defendants were ordered to pay roughly $10bn in damages, of which PMI’s share was around $2.5bn. As a result of the appeal decision, the defendant entities (Canadian subsidiaries) all filed for CCAA protection, which lets them restructure their affairs and avoid bankruptcy. While the CCAA process is ongoing, all tobacco-related litigation in Canada is stayed – meaning the other 17 cases can’t move forward.

One thing I’d be particularly concerned about is that 10 of the outstanding cases currently stayed were filed by the provinces of Canada to “recover the health care costs they have incurred, and will incur, resulting from tobacco related wrong”. If those cases succeeded, I don’t even want to think about the judgement amounts that could be involved. I doubt we’ll know the outcomes there for another decade, but this is one of the known unknowns that would bother me if I was a PMI investor.

I should note that PMI deconsolidated RBH from their financial statements in 2019 following the CCAA filing, and now accounts for that business as an equity investment. It doesn’t appear that PMI is generating any equity income from that business, and they indicated last year that cash is effectively trapped in Canada for the time being. I think it’s reasonably likely that any cash in that business today will ultimately go toward paying the judgements discussed earlier, but it’s possible that some of that cash gets unlocked should a positive resolution play out. If there is a positive resolution on all the Canadian litigation and CCAA proceedings, the Canadian business could also get reconsolidated and start generating cash for PMI again. This wouldn’t move the needle a ton (apparently Canada was 4-5% of revenue prior to deconsolidation), but it’s something to watch for.

Outside of Canada, none of the other litigation seems to be that material of a risk at first glance… but I’m no lawyer, and all it takes is one extreme judgement like we saw in Canada to have significant financial implications for PMI. There is also all the future litigation that hasn’t been filed but is sure to come. Given the base rates in this arena, I’d call this a low-probability but high-consequence type of tail risk.

Inflation

Exhibit T shows PMIs historical gross margin, and it tells an interesting story. We can see that gross margins peaked in 2012 with the peak in Combustible net revenue, and then declined through 2017. Post-2017 margins started to expand again, which is largely attributable to proportional growth from the SFP business where gross margins are estimated to be about 10% higher than Combustibles. Then in 2022 there was a significant step change lower with gross margins dropping by roughly 7% through 4Q22. Part of that decline was tied to one-off items like costs associated with the conflict in Ukraine and an inventory revaluation charge tied to the Swedish Match acquisition. But even after adjusting for those items it looks like gross margins compressed by ~4-5%, and the primary culprit here is inflation.

Inflation obviously impacts direct wages, materials, energy, and transport costs, and clearly in 2022 those items inflated more than PMI could offset with price increases. In recent conference calls, management has indicated that they can claw back some of that margin with future price increases but noted that there is a lag to overcoming that. Encouragingly, we have started to see gross margin expand through 2023 and part of the reason is that PMI is increasing prices faster than they have in recent years (Exhibit U).

To the extent that there were investor concerns about inflation, I think the most recent price/margin data helps put those concerns at ease. PMI should be able to claw back those higher costs through price over time.

The gazillion other small things

Unfortunately, this is just one of those businesses that perpetually grapples with new regulatory headwinds. Recall the excise tax increases on HTUs in Germany and Japan, or the new regulations in Mexico and New Zealand that should go a long way toward kneecapping cigarette consumption. In addition to these more obvious challenges there are small things like an upcoming flavor ban on heated tobacco in the EU that is set to take hold this year. It’s unclear how that might impact HTU demand, although when the EU banned flavor bonds and menthol for combustibles years ago it didn’t have a huge impact on cigarette volume.

I think it’s easy to look at these events in isolation as one-time challenges. But it’s important to remember that there are new – albeit different – challenges cropping up for PMI all the time. In my view, investors should expect that there will be perpetual headwinds to margin expansion and unit growth, and temper financial expectations as as a result (err on the side of caution more than normal).

Capital Allocation, Financial Position, and ROIC

PMI generates a ton of cash and has relatively few reinvestment opportunities – so few that their organic reinvestment rate has averaged <10% over the last decade. As a result, they return a significant portion of their FCF to investors. Over the last ten years they’ve paid out a little more than 70% of their operating cash flow in dividends, and another 12% via buybacks. Exhibit V shows T10Y sources and uses of cash and illustrates this dynamic perfectly. Note that cash flow from operations has covered significant capital returns, all capex, payments to Altria, NCI, and equity investments. They’ve only leaned on incremental debt to fund M&A, and ~75% of that incremental debt was used to acquire Swedish Match last year. Given everything we know about this business, I think it’s incredibly likely that they continue to return >80% of FCF to shareholders via dividends and buybacks.

With the Swedish Match acquisition, PMI’s ND/EBITDA increased considerably and ended FY22 at 2.8x (even if we include a full year contribution from Swedish Match). I’ve shown historical ND/EBITDA in Exhibit W, and you can see that this is the most levered that PMI has ever been, and current leverage is quite a bit higher than their target leverage range which is “a bit below 2.0x”. Fortunately, most of this debt is fixed-rate and the weighted-average interest rate is sub-4% this year. In fact, roughly two thirds of this debt is fixed for the next five years at ~4%. Given how much cash PMI generates, and how stable this business tends to be, the high leverage at this point in time doesn’t concern me. That being said, I wouldn’t expect any buybacks until that ND/EBITDA ratio gets back to ~2.0x. They’ll close part of that gap with modest EBITDA growth, but I do think they’ll have to repay 20-25% of the current debt load to get there, which probably pushes buybacks out a few years.

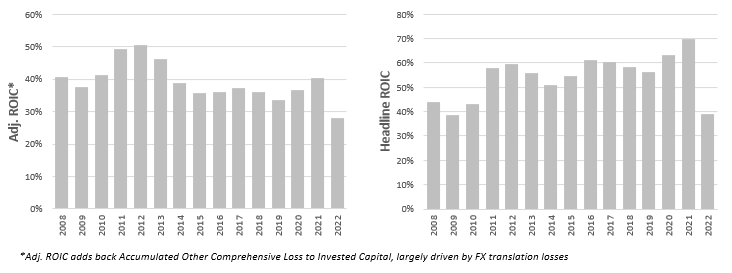

All told, PMI’s capital allocation priorities are clear in both the short term (debt repayment and dividends), and the long term (dividends and buybacks). Aside from their investments in Wellness and Healthcare PMI has been pretty disciplined about deploying capital, and that has led to some exceptional returns on invested capital (Exhibit X). That high ROIC doesn’t matter a ton given the lack of reinvestment opportunities, but it’s still important to recognize how capital efficient this business is. To the extent that PMI invests in new capacity for HTUs and oral nicotine, I think it’s reasonable to expect that they’ll generate an incremental ROIC comparable to what they’ve generated historically.

Management & Governance

There’s really not much to say on this front. Because most of PMI’s FCF gets returned to shareholders and the organic reinvestment opportunity is small, the managers of this business play a smaller role in determining shareholder outcomes than might be the case for an average business. That’s especially true considering the mature nature of this industry, and how much is outside of managements control. Sure, there are strategic initiatives like the SFP evolution that require some navigating, but now that the SFP train has left the station it’s more about operational execution than anything - the track record there is great and the roadmap is unambiguous.

Said differently, if the entire executive team turned over tomorrow, would my expectations for strategy and future financial performance be that different? I doubt it. Nevertheless, it’s helpful to quickly assess executive alignment.

Incentive plans for the NEOs seem pretty standard. CEO compensation is split 67/22/11% LTIP/STIP/Salary, while other NEOs are 46/27/27% LTIP/STIP/Salary. STIPs are annual cash bonuses based on several largely quantifiable KPIs including market share, HTU shipment volume, Adjusted Net Revenue, Adjusted OI, Operating Cash Flow, and Strategic Initiatives (like the agreement with Altria and the acquisition of Swedish Match). The LTIP is paid 60/40% with PSUs/RSUs, where the PSUs are a function of both relative and absolute TSR (40%), EPS growth (30%), and SFP revenue as a percentage of the total business targets (30%). Notably there aren’t any return on capital metrics in there, although I’m not sure that’s wholly relevant given their low reinvestment rate.

Insider ownership leaves me a little wanting – the NEOs cumulatively own $73mn of stock but were paid more than $37mn in total compensation last year. Against that backdrop inside ownership feels a little light.

At the same time, if the executive team owned $500mn of PMI stock, would it change their behavior? What if ROIC was a core KPI in calculating PSU payouts - would that change behavior? Maybe they wouldn’t have pursued the Wellness & Healthcare acquisitions and subsequent spend, but that’s not even obvious to me considering the option value there. So, I loosely hold the view that “no”, higher ownership and modest tweaks to LTIP/STIP KPIs wouldn’t change behavior materially. All told, alignment seems good enough, and there aren’t any glaring red flags here that would keep me up at night.

Valuation

You can find my DCF model below, complete with assumptions that I’d be comfortable underwriting.

What does the current share price imply about market expectations?

I like to start thinking about valuation by figuring out what the market is pricing in, so I changed the key driver assumptions in my DCF model such that the fair value estimate was equivalent to the current price.

For the Combustible business I had to assume a unit growth CAGR of -5.0% over the next decade, which is reasonably consistent with the last decade. I think it’s likely that PMI’s HTU business continues to cannibalize some of their cigarette business, and if that’s true then the implied decline in industry cigarette units would be slightly better than -5%. That feels a tad optimistic to me, but not totally unreasonable. I then had to assume that gross revenue/stick (in US$) inflated at 2.5%/year, but that excise tax rates continued to increase such that net revenue/stick (in US$) inflated at just 1.0%/year. That net revenue CAGR seems totally reasonable, and I’ve illustrated what that looks like in Exhibit Y.

Combined, these assumptions drive a -4% CAGR in Combustible net revenue (Exhibit Z). I’d personally want to underwrite more punitive assumptions, but I wouldn’t be surprised if this is how the future played out.

On the SFP front, let’s start with IQOS where I had to assume that PMIs HTU unit sales roughly triple from 2022-2032. In that case, there would be roughly 70-75mn people consuming ~12 HTUs/day ten years from now vs 25mn IQOS users at ~12 HTUs/day at the end of 2022. That doesn’t seem like an impossibility given how many markets they have yet to penetrate (including the United States), their penetration level in existing markets, and the new innovations that have yet to really come to market like BONDS. Exhibit AA shows what PMI’s combined cigarette + HTU unit sales would look like if HTU unit sales tripled. If the global cigarette + HTU market shrunk at 2%/year (ex. China), in-line with the T10Y decline, this would imply that PMI picks up roughly 5% of aggregate market share. Interestingly, if PMI ceded an additional 2-3% share in the cigarette market, this would imply that they also cede share in the HTU market (from 75% to 60%), although remain the dominant player in the HTU category. That feels a tad optimistic to me as well, but I can wrap my head around these implied expectations.

On the pricing front, I had to assume ~1.0% gross revenue/stick inflation. I suspect PMI will be able to increase gross prices (in US$) at 2-3%/year, so this would imply that their HTU mix shifts toward lower income countries that drag down the average price point, which makes sense given implied expectations for HTU unit growth. The market also seems to be pricing in some modest increase in HTU excise tax rates, but ultimately has the excise tax rate spread between cigarettes and HTUs remaining pretty constant. The net result is that net revenue/stick stays roughly flat over the next decade.

On Swedish Match I had to assume that ZYN revenue quintuples from 2022 and the rest of the business shrinks at 1%/year. That’s not as crazy as it sounds given that ZYN shipment volumes in the U.S. are still growing at 50% y/y as of 2Q23, and PMI hasn’t even started their international expansion journey outside of the U.S. and Scandinavia. I then assumed that Wellness & Healthcare is a bust, and no other SFP really emerges in this portfolio.

Exhibit AC shows the combined net revenue assumptions implied by the current share price. Effectively, the market expects that growth from IQOS and ZYN should more than offset a declining Combustible business, such that total net revenue grows at roughly 3%/year from 2023-2032. I also want to highlight that PMI gets full value for their Russia business here, which would represent some mid-to-high single digit share of net revenue.

Below net revenue, I then had to assume that there is some EBIT Margin expansion (Exhibit AD). Part of this is just price inflation catching up to COGS inflation, but the majority is driven by the mix shift from cigarettes to higher-margin HTUs/oral nicotine. The combination of net revenue growth and margin expansion drives a 4.5% CAGR in operating income from 2023-2032.

I assume that capital intensity remains constant as they repurpose existing cigarette capacity for HTU production, and that PMI brings leverage down to ~2.0x ND/EBITDA by 2026. The vast majority of FCF is distributed via dividends, or otherwise used to repurchase shares at fair value once leverage comes back to target.

Finally, to make the DCF spit out a fair value estimate that approximates the current price I had to use a 9.0% cost of equity, 6.0% cost of debt, 1.0% terminal growth rate, and 25% terminal ROIC – collectively, that works out to a 12.5x terminal P/E multiple.

As I look at what the current share price seems to imply about key drivers, it’s difficult for me to get excited. While some of the implied assumptions seem reasonable enough, others are more generous than I’d feel comfortable underwriting (in particular, the HTU excise tax rates). I certainly wouldn’t take the “over” on these expectations with any confidence.

What would I feel comfortable underwriting?

To start, I think it’s reasonable to assume that the decline in cigarette unit consumption will accelerate over time, particularly relative to the last 10 years. There are very few countries where cigarette consumption is still growing, which wasn’t necessarily true 6-7 years ago. There has also been a new wave of smoking bans, like the stuff we’ve seen in Mexico and New Zealand, and I’m sure those won’t be the only countries to take those steps. Finally, PMI and the other large incumbents are all investing heavily in smokefree products, and I suspect that smoker conversion will accelerate as these products gain popularity.

On the pricing front, I do think PMI can increase gross prices (in US$) at 2.5%/year, but excise taxes will likely eat most of that price uplift such that net price will struggle to eek out growth of 1.0%/year.

This might be overly punitive, but I’d also want to write off Russia - all sales go to zero, PMI loses the trapped cash, and they experience some margin compression (fewer dollars to cover fixed costs). As it relates to the Combustible business, I’ve taken Russia volumes down to nil in 2024. Exhibit AE summarizes the key driver estimates I’d be comfortable underwriting for Combustibles. Note that unit sales decline at about 6.5%/year excluding Russia, and roughly 7.5%/year including Russia.

The net effect is a >50% decline in net revenue from the Combustible business over the next decade (Exhibit AF), which would take cigarette volume down 70% from the peak in 2012. I’d happily underwrite this scenario.

In the SFP segment I do think IQOS will be a substantially larger business a decade from now, and I’d feel comfortable underwriting a 10-11% CAGR in HTU units through 2032 (~3x in unit sales). Exhibit AG shows the combined cigarette + HTU unit volume assumptions I’d be comfortable underwriting, and I should point out that combined unit volume still declines. Implicitly, this would mean some combination of A) the industry shrinks much faster than it has been, B) IQOS market share drops by more than half as new entrants take share, or C) IQOS never achieves broader appeal with lower income groups, and IQOS HTU sales primarily cannibalize PMI’s existing cigarette business. For context, if the number of combined cigarettes + HTUs consumed globally declined by 3%/year, this would imply that PMI’s combined market share goes from 28.5% in 2Q23 to 31.5% by 2032.

I think PMI can increase HTU gross prices with inflation (if not slightly above), but I also think that for HTU unit sales to triple PMI will have to succeed in lower income markets. New devices like BONDS should contribute to that success but will drag down average gross revenue/stick. Weighing all these factors, I’d be comfortable underwriting a 1.5% annual increase in gross revenue/stick (in US$).

Where I likely have the most punitive view relative to implied expectations is HTU excise taxes – I think HTU excise taxes are likely to increase significantly over the next decade. We’ve already seen Germany and Japan hike excise taxes such that they are at 80-85% of the cigarette rate (vs. a weighted average for PMI of about 48-50% last year). It’s impossible to predict when these changes will happen, but I’d want to underwrite an HTU excise tax that hits 75% of the comparable cigarette rate in ten years. Exhibit AH summarizes these assumptions, and the implication for net revenue/stick is significant – because of the excise tax increase, net revenue per stick falls by 25%. That might seem too aggressive, but I’d draw your attention to the 11% decline in net revenue/stick in 2022 following the tax hike in Germany/Japan – this is a real risk that has legs. Despite this decline, net revenue/stick would still be 1.6x higher for HTUs than cigarettes in ten years, so the economics would still be significantly better.

With Swedish Match I think it’s clear that ZYN is still early. Annualized 2Q23 U.S. shipment volumes were roughly 360mn cans, and 2Q23 shipment volumes were still growing 53% y/y. The range of outcomes here feels really wide, but I’d be comfortable assuming that annual U.S. ZYN shipments hit 800mn cans in ten years. It’s less clear what the international appeal might be, but I’m comfortable underwriting 600mn cans/year internationally in a decade. I hold revenue/can flat given PMI would certainly have pricing power but the geographic mix shift would likely offset all of that impact. For the rest of Swedish Match I assume a gradual decline (chewing tobacco, cigars, snus, etc.), and the net result is a ~10% top line CAGR over the next decade.

I wouldn’t be willing to pay for other SFP success like new vape products or success in Wellness and Healthcare.

Exhibit AI shows the combined net revenue assumptions I’d be comfortable underwriting, which works out to almost no aggregate top-line growth over the next decade (sub-1.0% from 2023-2032).

I assume some modest improvement in Combustible gross margins in the immediate future, but gradual margin compression thereafter as the Combustible business shrinks and it becomes harder to optimize manufacturing/distribution. The shift from Combustibles to SFP drives some margin accretion, but if HTU excise taxes increase considerably then HTU gross margins (on net revenue) actually decline! As such, even as IQOS and ZYN grow proportionally, PMI would realize little-to-no operating margin uplift. You can see all the margin drivers in my model, but Exhibit AJ shows aggregate EBIT margins and the resulting EBIT that I’d implicitly be happy to pay for.

I hold capital intensity roughly flat such that PMI spends a little more than $1.0bn/year in capex - once we also strip off taxes, interest, NCI, NWC, and pension costs, this scenario has PMI generating $9-11bn of FCFE every year. To hit the ~2.0x ND/EBITDA target I also have PMI paying down nearly $9.0bn of debt over the next 5 years, after which all FCF in excess of dividend payments gets directed toward buybacks.

I use a 9.0% cost of equity, 6.0% cost of debt, and 0% terminal growth rate, which implies that I’d be comfortable underwriting an 11.0x terminal P/E multiple. Despite success with IQOS and ZYN, I do think the nicotine industry will be perpetually challenged and it’s difficult to wrap my head around paying for any long-term growth as a result, particularly when cigarettes would still represent 30% of this business in a decade (using my assumptions), HTU’s themselves are still quite bad for your health, and HTU excise tax rates would still be 25% lower than cigarettes.

My DCF model suggests that fair value using these assumptions is ~$75/share, which is ~25% lower than the current share price (see Exhibit AK for a screenshot of my DCF tab).

If I kept HTU excise tax rates flat from 2022 (such that net revenue/stick grew at 1.5%/year instead of declining by 25%), and held every other assumption unchanged, my fair value estimate would be ~$102/share – almost exactly where PMI is trading today. Against that backdrop, I’d argue that my differentiated pessimism is largely rooted in a view that HTU excise tax rates are unsustainably low. I suppose you could also argue that my unit growth assumptions or terminal multiple are a little conservative, but that matters less than HTU excise taxes.

All told, I’d love to own this business closer to $70-75/share. I like that it’s not exposed to the economic cycle, that they’re aggressively shifting away from cigarettes, and that there are few real competitors. But at this price it feels like the risk/reward is stacked against me, and I can’t see myself taking the over on implied expectations, so for now I’ll stick it on the watchlist.

PMI does have an investor day scheduled for this September, and I’m curious to see what they have to share. Maybe some new information changes my view. Maybe not! Either way, I plan to post an update to the thesis if that IR Day proves eventful.

As always, if you have any questions or disagree with any of the analysis/views, please fire away in the comments below. You can also reach me on Twitter or the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

Given that cigarettes are the only addictive substance that doesn't produce any noticable form of intoxication, doesn't augment road deaths, domestic violence or criminality, but alcohol which does all these things is available at practically every street corner supermarket and regulated to a minimal degree, I have to wonder about all this misplaced piety