Investment Thesis

GoodRx GDRX 0.00%↑ addresses a huge problem for millions of Americans: Rx drug affordability. The founders built a discount service that helps uninsured/underinsured consumers save an average of 70% off retail pharmacy cash prices, which helps people afford medication that might have otherwise been out of reach. The core prescription business has multiple competitive advantages that allows GDRX to offer better discounted prices than any competitor, acquire customers more effectively, retain most of those customers, and easily build out adjacent products and services at scale. The company is currently the dominant player in the space and is primed to take share in their primary markets. In addition, I estimate that industry penetration for prescription discount programs like GoodRx is only 10%, which should increase many-fold over the next decade. In my view, the current share price does not reflect this industry potential or the company’s competitive position. My base-case user growth estimates are higher than consensus in both the near-term and long-term.

Advertising is the single biggest cost item at GDRX, and much of that spend is a direct function of growth. In my view, this growth-related ad spending should be capitalized rather than expensed, and hides the true earnings power of the business, which I suspect the market also misses.

Despite ~50% top-line growth over the last four years, GDRX has consistently generated positive FCF, and now has an enviable net cash position. I expect that cash will accrue to the balance sheet quickly, which can eventually be deployed on M&A and new initiatives. In my experience, share prices don’t often reflect this option value.

Lastly, the management team is clearly passionate about solving problems anywhere in the patient health journey. The founders still manage the business today, and have consistently exhibited a relentless focus on customers and products. As large shareholders in the business, they are aligned well with the interests of Class A shareholders. Inside ownership among non-executive employees also appears high.

There are unique risks to this business that would be silly to ignore, specifically healthcare reform. I proactively reflect the impact of some reform in my base case. Other risks seem to be overexaggerated. For example, PBM concentration and the “Amazon risk”.

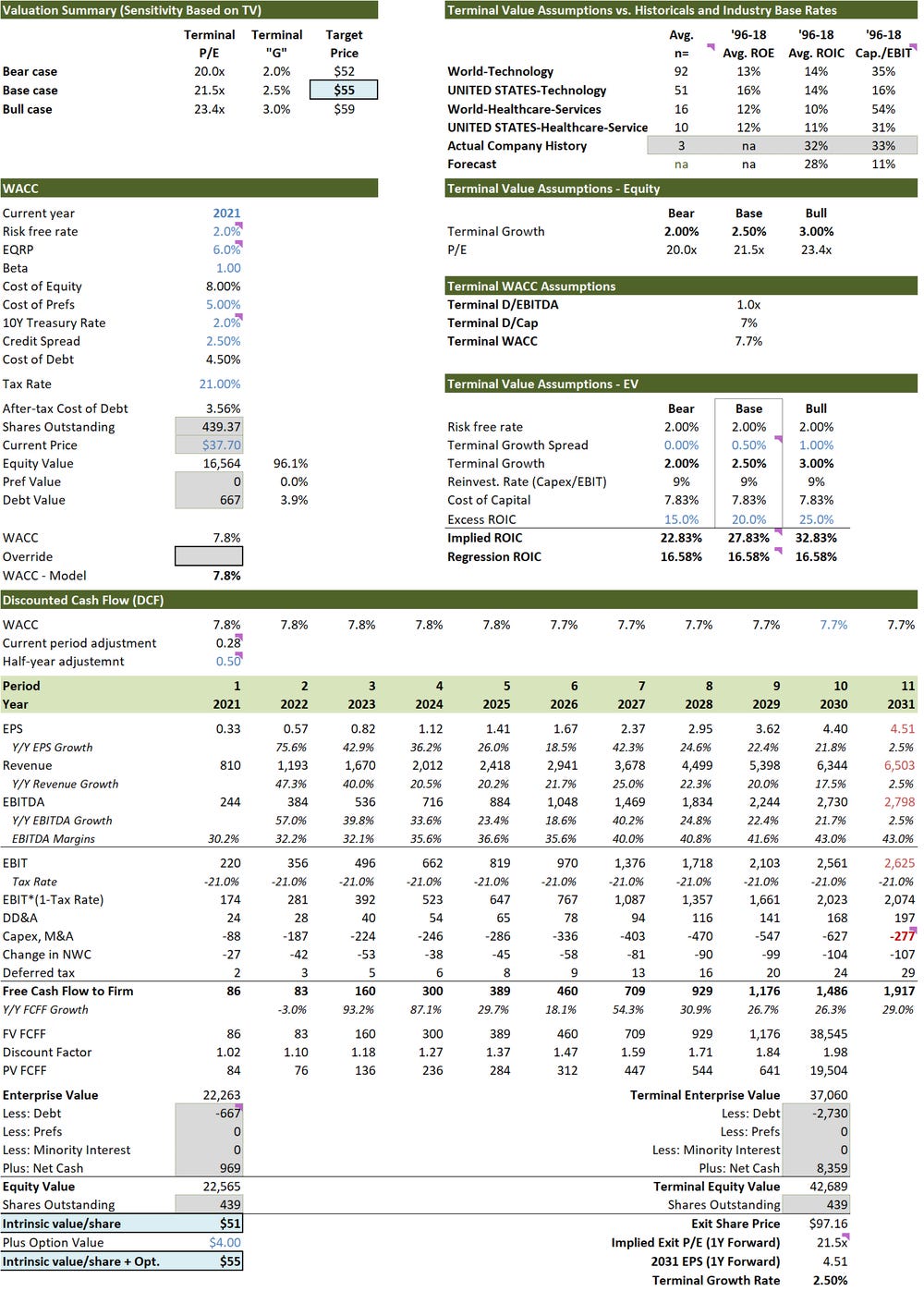

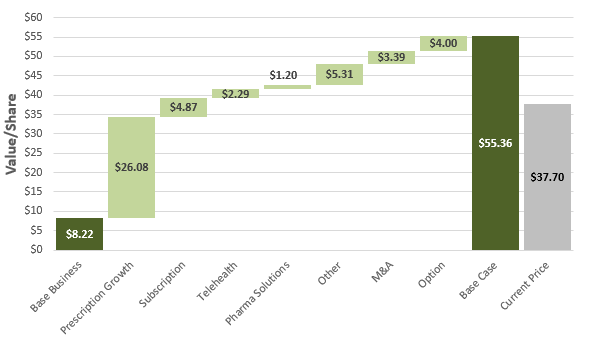

My base case suggests that fair value is $55/share, which represents ~50% upside to the current price of $38/share. My bear and bull case at $27/share and $96/share respectively also suggest that risk is meaningfully skewed to the upside. To summarize: this is a great business; run by exceptional people; with an enviable balance sheet; solving important problems for consumers; and, trading at what I view to be an attractive valuation.

As always, I encourage you to reach out with feedback or comments if you disagree with any of my analysis. I can be reached at the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

Prescription Drug Market in the U.S.

Above-average spending

The U.S. has an extremely laissez-faire healthcare system. It is the only OECD country without some form of universal health coverage and relies heavily on a decentralized multi-payer model to fund healthcare expenditures. While pros and cons exist under every healthcare model, the U.S. approach has clearly resulted in abnormally high health spending per capita (Exhibit A). Despite higher spending, most data shows that health outcomes in the U.S. are worse than other OECD countries, even after adjusting for nuances like above-average obesity rates. For example, a 2020 study by the Commonwealth Fund notes that the U.S. has the highest rate of avoidable deaths in the world (measured as “premature deaths from conditions that are considered preventable with timely access to effective and quality health care”).

The same theme persists at a more granular level if we isolate for spending on prescription (Rx) drugs. In absolute terms, the U.S. spends significantly more than any other OECD country (130% more than average), and even if we GDP-adjust those figures, the U.S. spends more than everyone except Greece and Bulgaria (50% more than average).

It’s also difficult to explain above-average spending on more frequent usage. In 2019, total U.S. prescriptions/capita were 32% lower than Canada. Instead, the primary explanatory variable seems to be above-average pharmaceutical prices. Exhibit C shows the U.S. price premium for popular branded drugs relative to a basket of prices from Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. What’s more, the IMS found that 70% of the most popular brand-name drugs are manufactured outside of the U.S. and are still profitably sold in these other markets at much lower prices. Most of the data I’ve found shows that price discrepancies in the U.S. for generic drugs are also significant.

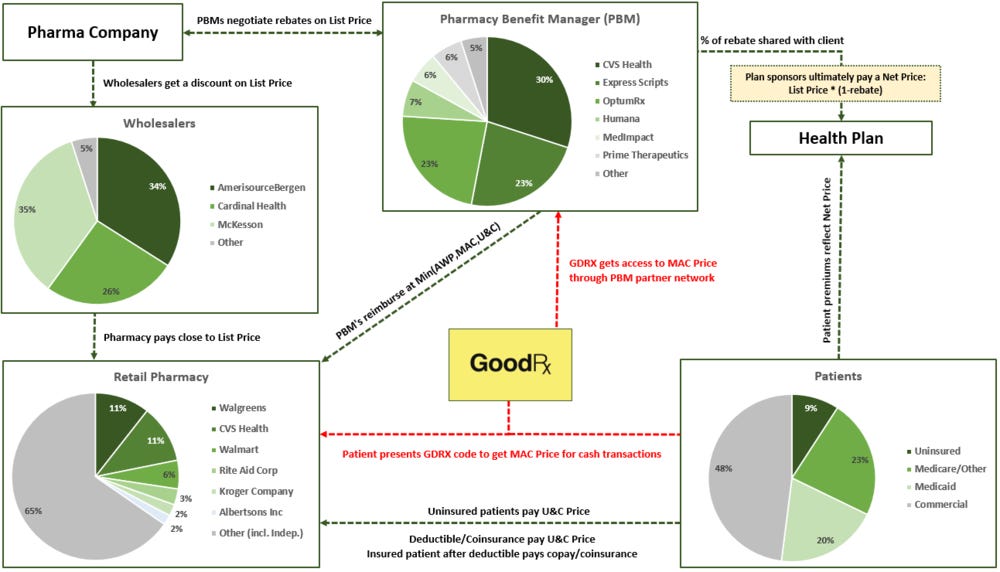

The system

To understand why drug prices are so much higher in the U.S. it’s worth exploring how the system works. Exhibit D shows an industry map that sets the stage for the remainder of this section.

Drug manufacturers sell drugs to wholesalers at a discount to their list price. Wholesalers mark those drugs back up and distribute them to pharmacies. When a pharmacy sells a Rx drug to a cash paying customer (uninsured/underinsured), they do so at the usual and customary (U&C) price, and earn a spread between the U&C price and the acquisition cost. When a pharmacy sells a Rx drug to an insured customer, they get reimbursed by a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM). PBMs negotiate reimbursement rates with pharmacies that are the lesser of:

The Average Wholesale Price (AWP) minus a percentage plus a dispensing fee (the AWP is calculated as the pharmacy acquisition cost plus a 20-25% markup)

The Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) plus a dispensing fee

The U&C price

Pharmacies have full control over setting U&C prices. If they set the U&C price under the AWP or MAC, then they forego reimbursement revenue from PBMs. Each PBM negotiates MAC prices with pharmacies in their network, and MAC prices can vary significantly by PBM and pharmacy. MAC pricing is painfully opaque, but I imagine that the difference in average MAC prices between OptumRx and Prime Therapeutics is large. As a result, pharmacies set the U&C price above the highest MAC price that any one PBM would pay. This might mean 10% over the Prime Therapeutics MAC price but 40% above the OptumRx MAC price. As a result, U&C markups tend to be high – they never want to leave money on the table. In the most egregious examples I’ve found, U&C markups relative to acquisition cost are in the 1,000%+ range, and the average U&C markup on generics must be somewhere in the 100-300% range. It really sucks to be a cash paying patient. Credit goes out to Richard Chu for explaining this better than I could (link).

AWP, MAC, and U&C prices are all ultimately tied to list prices set by pharmaceutical companies, and list price inflation has been extraordinary. There are lots of explanatory factors, but a big reason is that there is a bifurcation in pricing that arises from PBM and manufacturer rebate negotiations: list prices for some, and net prices for others.

List vs. Net Price

Health plans have something called a formulary, which is a list of covered medications that the plan will cover. Drugs in the formulary are placed on different tiers, and both copayment and coinsurance amounts depend on which tier the drug falls under for a given health plan. Drugs are placed in a given tier based on factors like drug usage and clinical effectiveness, but net cost to the sponsor tends to be the primary determinant.

Health plans hire pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to help them build and manage the formulary, determine tiers, contract with pharmacies, and negotiate rebates. Drug manufacturers compete to get favorably placed on formularies by offering rebates to PBMs. All else equal, the manufacturer will offer a greater rebate to be placed on the first or second tier of a plan (lower cost to the health plan), which typically results in greater volume because of the lower out-of-pocket cost to patients. While most of the rebate is passed to the PBM client (health plan), the PBM keeps a percentage of the rebate as a fee for providing the service.

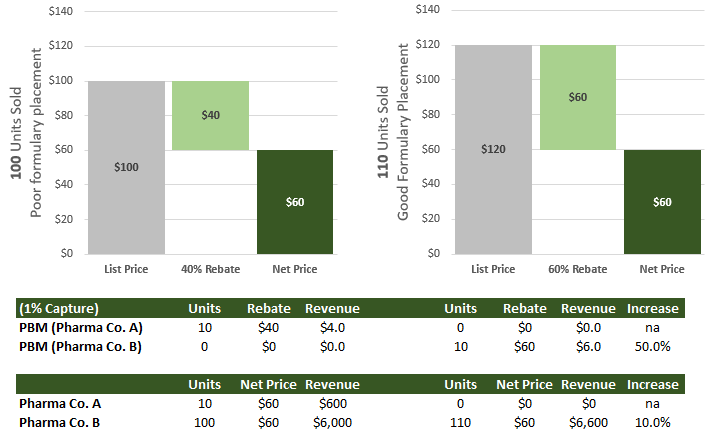

As profit-maximizing entities, PBM’s will always choose the drug with the highest rebate, so long as the net price that they can provide to a health plan client is the same as an identical drug with a lower rebate. Similarly, drug manufacturers optimize for volume and net price (list price after rebates). If they want to keep net price flat, but increase units sold by getting favorable placement in a formulary, all they have to do is simultaneously increase the list price and the rebate. Numerous studies also show that the price elasticity of demand for Rx drugs is somewhere in the -0.2 to -0.6 range, so a higher list prices doesn’t even reduce Rx revenue outside of the PBM channel. Exhibit E shows a hypothetical illustration where both negotiating parties - the PBM and the drug manufacturer - win if list prices increase. The PBM procures 10 units of the drug for a particular health plan in either scenario, but receives significantly more revenue from the higher-rebate drug. The drug manufacturer can also see a revenue uplift from securing higher volume and keeping net price flat.

This is an overly simplified illustration, but in the absence of better regulation it’s easy to see how existing incentives can cause significant inflation in list prices. Merck & Co., one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the U.S., breaks out inflation for both list prices and net prices over the last decade (Exhibit F). List prices increased at 8.18%/year, while net prices increased at just 3.75%/year as rebates went from 27% to 44%. Aggregate U.S. data from the National Institute of Health (NIH) shows that this is a widespread theme. All uninsured patients, spending under deductibles, and most coinsurance amounts are exposed to this list price inflation, which drags up the national average spend per capita on Rx drugs.

NIH data also shows that the national average rebate for commercial plans is 40-50%, while the rebate for Medicaid is closer to 80%. This makes complete sense: Medicaid covers more patients than even the largest PBM, which means that they have more bargaining power than any individual PBM (not to mention different incentives). This illuminates another issue. Most countries with lower Rx spending/capita have single-payer systems, or a multi-payer system where a single government entity negotiates with drug manufacturers. The U.S. operates under a lightly regulated and decentralized multi-payer system, which leads to fragmentation and lower bargaining power for each participant, particularly commercial health plans.

More patients exposed to List Prices

All spending by uninsured patients is exposed to list prices, but it doesn’t stop there. Health plans share the burden of drug costs with the patient through three mechanisms: deductibles, copays, and/or coinsurance.

When an insured patient pays for a drug before their deductible is met, they typically pay the U&C price; they don’t benefit from rebates. After the deductible is met, patients are required to cover either a copay or coinsurance. Copays are fixed fees, but coinsurance is tied to drug prices. According to KFF, the average copayment for 3-tier plans is $11, $33, and $59 for the first, second, and third tier respectively. The average coinsurance rate is 18%, 24%, and 34% for those same tiers. Oddly enough, the coinsurance calculation is based on U&C prices, not rebated prices. So, all deductible and coinsurance payments are also exposed to list prices.

Exhibit G shows how the cost-sharing split has changed over time, and the biggest takeaway is that a greater share of out-of-pocket spending is increasingly forced to pay U&C prices. In fact, data from the NCHS shows that enrollment in high deductible health plans (HDHPs) among covered employees went from 15% in 2007 to nearly 50% today. Patients with low deductible plans and/or low coinsurance rates reap all the benefits of rebated prices, but for everyone else, list price inflation is creating a growing affordability problem and contributing to increasing Rx spend/capita.

Because the system is so convoluted, many other nuances help explain unusually high drug prices, like the “Gag Clause”. Many commercial contracts between PBMs and pharmacies had Gag Clauses which prevented the pharmacist from informing patients that the U&C price of a prescription might be less than the copay cost of insurance. As a result, many patients were paying more for medication than they should. In 2018, a new law was passed that banned this absurd practice, which should help combat rising Rx spending. Even still, pricing anomalies abound, and it’s not worth going down every rabbit hole because I think the primary issues are the decentralized multi-payer vs. single-payer structure, light regulation, and unusual incentives. In other words, the primary problems are structural and not easy to fix.

One obvious consequence of high drug prices is that a significant portion of the population will struggle to pay for treatment. In 2014, the Commonwealth Fund did a study comparing cost-related non-adherence for Rx medicine, and found that more than 16% of respondents either didn’t fill a prescription or skipped doses in the U.S. because of price, versus an average of just 4% for other countries in the study. An internal GoodRx estimate found high prices to be even more onerous on patients, and shows that 20-30% of prescriptions in the U.S. aren’t filled. This is clearly a problem begging for a solution, and GDRX provides one.

The GoodRx Keystone: Prescription Services

The service, consumer, and value proposition

Roughly 90% of GDRX revenue today comes from the core prescription platform, which is a mobile-first marketplace where consumers can search and compare Rx drug prices across a wide range of retail pharmacies. Through the app, GDRX provides a distinct discount card that consumers can present at the pharmacy counter to receive significant discounts on U&C prices. This is how they do it.

Every PBM has a pharmacy network, whose pharmacy members sign contracts that allow consumers with insurance to easily fill prescriptions at those locations. Most pharmacies are part of one or multiple PBM networks. In exchange for access to those insured patients, the pharmacy has to accept discount cards that give consumers access to the PBM network rate (MAC list). PBM-backed discount programs can therefore provide significant discounts to U&C prices. Most large chain-pharmacies don’t mind foregoing the U&C margin from accepting discount cards if they can secure access to insured patients and drive foot traffic through stores that sell other goods (like groceries). On the other hand, small independent pharmacies who rely solely on drug sales tend to hate this because they can’t make up the lost profit from high U&C markups on purchases of groceries or other items. This explains why many independent pharmacies aren’t part of PBM networks and refuse to accept discount cards.

PBMs only get paid for drugs sold in-network when they adjudicate the claim, and typical cash transactions at the U&C price fall outside of the network. So, GDRX approached all the PBMs and said:

“Hey, if you give us access to your network rate for our discount card service, we can you help you monetize this out-of-network patient spending. Not only does that include all uninsured/underinsured spending today, but it also includes all the potential spending we could monetize if cost-related non-adherence was reduced.”

If a patient purchases a drug outside of insurance using any discount code, the PBM who provided that discount gets paid a fee by the pharmacy (because the PBM adjudicates the claim). A portion of the fee is shared with GDRX for bringing the customer into the network, which allows GDRX to offer their service to consumers for free. On average, the GDRX fee works out to 14-15% of GMV. If the discount program didn’t exist, and that patient paid the U&C price, the PBM would earn nothing. Unsurprisingly, most PBMs signed contracts with GDRX. As a result, GDRX can help consumers access competitive prices for a wide range of drugs at >85% of all retail pharmacy locations in the country.

I originally expected that the majority of GDRX revenue would come from uninsured patients, but that turned out to be totally incorrect. While it’s true that uninsured patients make up a proportionally greater mix of their monthly active users (MAU) than the U.S. population, GDRX estimated that 74% of their MAU were actually insured patients.

This brings me to the three categories of users for the core GDRX prescription platform:

Uninsured: nearly 30 million Americans (9-10% of the population) lack health insurance. Literally every single person in this category can benefit from access to the GDRX platform and/or other discount programs to receive significant discounts on U&C prices.

High Deductible Health Plans (HDHP): as noted earlier, nearly 50% of commercial health plans are classified as HDHP. During the deductible phase of spending, members can choose to pay U&C prices that count toward the deductible, or use a GDRX discount code which doesn’t count toward the deductible. If a member expects annual Rx spending to significantly exceed the deductible, it often makes sense to forego the GDRX discount. However, in many instances, annual spending using a GDRX discount code will fall short of the deductible amount, in which case it definitely makes sense to use GDRX and bypass insurance.

High Copay/Coinsurance Plans: after a deductible is hit, plan members are typically on the hook for a copay or coinsurance. While this is often the cheapest option, sometimes the copay/coinsurance amount is higher than the cash price available with a GDRX discount (or a drug isn’t covered by the plan). I was surprised to learn this, but the cheapest Atorvastatin price I was shown in New York on the GDRX platform was $8.90, which is lower than the average copay amount of $10. At the virtual UBS TMT conference earlier this year, the CEO of GDRX provided a hilarious relevant anecdote:

A New York Times reporter called us up just a few years ago and was like, "I don't believe you guys. There's no way this works for insured customers." We actually went through the top 100 drugs in the country, comparing her New York Times co-pay against what GoodRx prices were, and we beat the co-pay 40% of the time. And that was assuming she'd even satisfied her deductible, which, as you know, is getting bigger and bigger.

For each of these categories, the value proposition is two-fold: help consumers search and compare prices across pharmacies (transparency), and help them save money on prescriptions (the average GDRX discount to U&C prices is 70%). Try searching for the price of Atorvastatin on the CVS Pharmacy website - you can’t find it. In the absence of platforms like GDRX, easily comparing drug prices across pharmacies is next to impossible.

Addressable Market and Penetration

U.S. Census Bureau statistics for 2019 show that there are 360 mln people covered by insurance polices, but only 294 mln insured patients. The implication is that 66 mln patients have dual coverage. It’s fair to assume that coverage is sufficiently attractive for these patients that we shouldn’t include them in the GDRX addressable market. That leaves us with 228 mln insured patients that could benefit from GDRX to some degree. At one extreme would be exceptionally high-deductible and/or high-copay plans where GDRX is a better alternative most of the time. In the middle is someone like that NYT’s reporter that might benefit from GDRX 40% of the time after their deductible is met. And at the other extreme is someone with pretty good insurance who still makes an effort to shop around but rarely finds a better deal than insurance.

I made an educated guess about what percentage of Rx spending/capita can be addressed by a discount card program for each cohort in the spectrum of insured users, which is illustrated in Exhibit K. On average, across all 228 mln addressable insured patients, I estimate that 35-40% of annual Rx spend could benefit from a discount card. At $1,200-1,300 of annual Rx spending/capita, this works out to more than $100 bln of addressable GMV.

For the 30 mln uninsured Americans, I see no reason that the full Rx spend/capita wouldn’t be well-served by a discount card of some sort, which works out to an addressable GMV of ~$40 bln.

In total, that’s $140-150 bln of GMV. I make some other adjustments to this figure, some up and some down, and the total adjusted GMV estimate ends up being ~$160 bln. For example, GDRX helps lower drug prices for the uninsured, which might lower GMV, but also helps alleviate cost-related non-adherence, which increases GMV. Most of the addressable patient spending also targets savings on U&C prices, which would be much higher than the average drug price used to calculate Rx spend/capita. All told, I think average GMV per addressable patient is in the $600-650 range, which is fairly close to the average GMV/patient being served by GDRX today.

In 2020, GDRX discount codes were used to facilitate ~$3.4 bln of GMV, which would represent a paltry 3% of the addressable market (up from 0.6% in 2016; Exhibit L). While there are other players in this space, GDRX has 2x the market share of the next closest competitor, which most likely means that <10% of GMV is currently being addressed by all direct competitors with a discount program. Some of these estimates are bound to be wrong, but I think this analysis generally shows that penetration is low and the runway for growth in this market is still extraordinary.

I think one primary contributing factor to low penetration is the demographic skew of Rx consumption. It almost doesn’t need to be said, but obviously Rx drug consumption goes up with age. Data from the CDC, AHRQ, and NIH show that 48% of total prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for patients older than 65, while 84% are for patients older than 45 (Exhibit M). These cohorts are less likely to utilize e-commerce services and mobile applications like GoodRx and Blink Health.

In fact, the Pew Research Center shows that smart phone penetration is barely 50% for the 65+ cohort. The percentage of that cohort utilizing mobile applications on those smartphones (outside of social) should also be small. Over the next few decades, as digital natives (the 18-44 cohort) get older, I suspect adoption of services like GoodRx will increase significantly. It wouldn’t surprise me if penetration for platforms like GDRX increased 10x in the next 1-2 decades, to the point that most eligible consumers were using these platforms to check prices and secure discounts.

Competitive Position

There are lots of competitors in this space, but before diving in, it’s worth highlighting what makes the GDRX platform so competitive:

Patents and Multiple PBM relationships: PBM’s often negotiate different prices for the same drug, so while PBM(A) might have the best negotiated rate on Drug(1), they might have a worse negotiated rate than PBM(B) on Drug(2). The price discrepancies between PBMs for an identical drug can be significant. If a discount card only utilizes one PBM, they will only be able to provide the best prices on certain drugs, and worse prices on others. In 2014, GDRX was issued a patent for the “methods and system for providing drug pricing information from multiple pharmacy benefit managers”. As a result of securing this patent (expires in 2034), the former Head of Digital Marketing at GDRX (employee #8) says that GDRX is the only competitor in the space that can contract with multiple PBMs and use their technology to show the lowest prices from that complete mix on the user interface; the patent wording is confusing, but that’s the gist of it. As a result, GDRX can offer equivalent or better prices in their discount service than any of their competitors. Since inception in 2011, GDRX has signed contracts with over a dozen different PBMs (Optum, Express Scripts, Humana, MedImpact, Navitus, etc.), and as that PBM network grew, the average discount generated by GDRX coupons went from 58% to >70%. It’s difficult to make an apples-to-apples comparison on average discounts amongst competitors (many are private), but my research suggests that GDRX offers the best pricing in this ecosystem. The other benefit of having multiple PBM relationships is that it increases the number of pharmacies that accept the GDRX discount code, and GDRX is accepted at more pharmacy locations than any other discount card (>70,000; >85%). I’m not a patent expert, so it’s hard to make any high-conviction statements about patent defensibility (maybe there is a work-around), but this strikes me as a significant competitive advantage.

Unique PBM contracts: Not only does GDRX have a great PBM network, but the contracts they’ve signed with those PBMs are quite attractive: they renew automatically; can’t be terminated “out of convenience”; and, prohibit PBMs from “circumventing the GDRX platform, redirecting volumes outside of platform or other protective measures”. In other words, once the claws sink in, they never come out, as evidenced by the fact that no PBM contract with GDRX has ever been terminated (since inception in 2011). Most importantly, if a contract ever did terminate, for whatever reason, each contract has a clause that allows GDRX to continue receiving payments from the PBM for multiple years after termination so long as consumers keep using the negotiated rate on file at the pharmacy. In my view, this contract structure significantly reduces top-line downside risk.

Sticky customers/recurring purchases: The CDC estimates that 60% of American adults have at least one chronic condition, and the vast majority of those chronic conditions (arthritis, diabetes, high blood pressure, etc.) require that patients perpetually take prescription medications. These patients typically refill prescriptions on 30 or 90-day cycles, which leads to recurring visits to a pharmacy. When a patient fills a prescription using a GDRX discount for the first time, that discount code gets saved to the patient profile at a pharmacy, which allows the patient to continue benefiting from discounted prices on all subsequent refills and new prescriptions with that pharmacy without having to re-present the discount code or revisit the price comparison process. Aside from price, the number one factor that impacts a patient’s pharmacy choice is location/convenience, which means they rarely switch pharmacies. As a result, once GDRX acquires a customer (word-of-mouth, doctor referral, or paid advertising), churn tends to be quite low. This helps explain why 80% of GDRX transactions come from repeat activity.

High customer satisfaction: GDRX has a self-reported NPS of 90 and 86 among consumers and health care practitioners respectively. I’m hesitant to place significant emphasis on self-reported NPS scores, but everywhere I look, I see glowing customer and doctor reviews. A core part of the GDRX strategy is to get patients the best pricing possible, even if that means directing a purchase away from their platform. For example, Walmart has a $4 generic drug program that can sometimes be cheaper than anything GDRX can offer, but GDRX will still show consumers these prices, even though the consumer won’t use a discount card (GDRX foregoes a fee). Over time, this builds trust with consumers, which contributes to a high NPS. This helps reduce CAC (word-of-mouth marketing is zero-cost), and increases LTV (high loyalty = low churn).

Scale - purchasing power: Many coupon businesses like SingleCare, rely on pharmacy discounts, whereas GDRX sources much of their pricing directly from PBMs. PBMs have significant negotiation power with pharmacies, which can lead to better pricing if sourced that way. In addition, PBMs can decide to be more or less competitive with the prices they offer through GDRX. A PBM that chooses to be more price competitive can capture more GDRX volume. GDRX is effectively aggregating demand on behalf of PBMs, and if that demand grows, competition to capture that growing user base amongst PBMs increases. This also helps explain why the average GDRX discount went from 58% to >70% as more PBM partners were added and MAU increased. New entrants in this space will have much lower MAU than GDRX, so even if they were somehow able to partner with multiple PBMs, the competition between PBMs to capture that MAU would be less fierce. Navitus and MedImpact both generated more than 10% of 2020 revenue on the platform, despite having just 2% and 6% share in the PBM market, which tells me they are pricing more aggressively on the GDRX platform than other large PBMs to capture more volume. GDRX also says that their platform tends to be the only significant source of direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales for most PBMs. I don’t see this competitive dynamic changing any time soon.

Scale - marketing: Paid advertising represents ~70% of total expenses at GDRX, and I suspect that this is the single biggest cost item for all competitors in the industry. Digital ad spending (eg. Google search words) is probably the most important paid customer acquisition channel, and GDRX can spend more money in that channel than any of their direct competitors. In fact, total ad spending at GDRX is many times larger than most of their competitors’ revenue. As a result, GDRX can more easily grow MAU in the medium term, and eventually spend less per acquired MAU which should contribute to margin expansion.

Customer acquisition strategy: this thread by @AznWeng does a great job at explaining the customer acquisition strategy. To summarize, GDRX does a great job in the paid search channel (like SEO), but also nails word-of-mouth marketing/referrals. Prescriptions originate with doctors, and because prescription adherence is important to doctors, they’re likely to recommend platforms that help consumers better afford medication. GDRX integrated their platform with many of the largest electronic health record (EHR) providers, which allows doctors to see GDRX pricing while sitting in their office with the patient. Consumer Reports surveyed doctors and found that almost all of the survey participants had recommended GDRX to patients, which has effectively nil incremental cost to GDRX. This jives well with the 86 NPS amongst health practitioners reported by the company. In theory, competitors could also integrate with EHR providers and get better at SEO marketing, but many won’t or will be slow to do so, and in the meantime, GDRX is likely to gain share.

I break the competitive landscape into three buckets: direct competitors, pharmacy discount programs, and mail-order (where I specifically mean Amazon).

Direct Competitors

In the direct competitor bucket we have Blink Health, WellRx, RetailMeNot Rx Saver, HelpRx, Inside Rx, NURX, SingleCare, FamilyWize, and a few others. It’s difficult - nay, impossible - to find any good public data on most of these private businesses. That being said, I don’t think any of these platforms come close to competing effectively with GDRX, and it’s worth walking through an example.

If I had to guess, Blink Health is probably the #2/3/4 direct competitor in the space. They originally worked with a single PBM, MedImpact, to connect with a pharmacy network and access discounts. That network included big chains like Walgreens and CVS, and Blink Health used to be accepted at 60,000+ pharmacy locations. I’m not totally sure what happened, but in 2017, Walgreens and CVS backed out of their pharmacy network, and Blink Health ended up terminating their arrangement with MedImpact. I’ve heard through the grapevine that Blink Health takes a much more antagonistic stance with pharmacies than GDRX, which doesn’t help. Within a year, Blink Health ended up partnering with Blue Eagle Health (an alternative PBM), and built their own pharmacy network (instead of relying on a PBM). Today, Blink Health is accepted at just 35,000 locations (compared to GDRX at 70,000+). On average, they also can’t beat GDRX on pricing because they lack the multi-PBM network. Now that they’ve fallen behind, Blink Health is at a pricing and scale disadvantage.

The pricing and scale disadvantage persist when I look at other competitors. When I use the 10001 zip code (NY), the lowest price I see for a common drug like Atorvastatin (30-tablet 40mg dose; physical pick-up) comes out to:

$8.90 for GoodRx (at multiple pharmacies)

$9.00 for Blink Health (at multiple pharmacies)

$9.10 for RxSaver (at multiple pharmacies)

$9.18 for WellRx (at Capsule Pharmacy; one cheaper option, but pharmacy was closed)

$32.99 for SingleCare (at CVS pharmacy)

$48.07 for FamilyWize (at CVS pharmacy)

HelpRx doesn’t even show a price, just a percentage discount, which was lower then competitors for the same pharmacy

When I search for other drugs, GoodRx pricing occasionally falls to the #2 slot (by a small margin), but they generally show up as the best price. I also note that the GDRX pharmacy network tends to be >2.0x larger than each of these competitors, and I can’t find a single instance of a competitor contracting with more than one PBM (although it’s possible I’ve missed some). That patent seems to be paying off. To be fair to SingleCare and FamilyWize, their pricing isn’t always that far off.

Pharmacy Discount Programs

The next bucket of competitors are large pharmacy chains, which occasionally have really competitive pricing. This would mostly just include Costco, Walmart, Walgreens, and CVS. When I compare the same Atorvastatin dose, I get $13.99 at Costco, $15.00 at Walmart, $15.00 at Walgreens, and can’t even find a price at CVS. What I find particularly crazy is that the typical U&C price at these same pharmacies is shown at $100-150, while small independent pharmacies show U&C prices in the $20-50 range. So even though these “discount” prices at large chain pharmacies are great relative to their standard U&C price, it’s still worse than GDRX (and is a prime example of how much U&C prices can get marked up). For a handful of drugs, it’s worth noting that big chains like Walmart do offer better prices than GDRX, but my best guess is that Walmart is treating these as loss leaders to get people in the store (where they’ll buy other stuff), and can’t sustainably do this for all drugs. The discount programs at these big pharmacy chains have the benefit of well known brands, but generally don’t seem price-competitive. I suspect that the third-party services like GDRX will take share from these chains over time.

It’s worth noting that some companies, like CVS, are vertically integrated: they own one of the largest PBMs and one of the largest retail pharmacy chains. The PBM contract prohibits CVS from “circumventing the GDRX platform, redirecting volumes outside of platform or other protective measures“. This is pretty vague language, but it lowers the risk of CVS volumes through GDRX getting redirected toward a CVS discount program.

Mail Order

Finally, the mail-order pharmacy channel could take share from the retail storefront, and Amazon is a serious mail-order competitor. Amazon bought PillPack in 2018, and launched Amazon Pharmacy in 2020. The core Amazon Pharmacy service is just a regular mail-order pharmacy, but Amazon Prime members also get free access to the Prime prescription savings benefit (basically a Rx discount card for cash-paying consumers). The Prime prescription savings benefit can be used at the online Amazon Pharmacy and at 50,000 participating retail pharmacy locations, and is basically a direct competitor to GDRX. If you’re a cash-paying consumer, and already a Prime member, it might make sense to use their discount card and fill a prescription online with free 2-day delivery. GDRX partners with mail-order pharmacies like GeniusRx and HealthWarehouse, but delivery times seem to be slightly worse than Amazon. It’s likely that Amazon can leverage their logistics network to drive better delivery times than competitors, and I’d be surprised if they didn’t take share in that channel, while also helping the channel grow.

That being said, GDRX has been a PillPack partner for years, and continues to partner with Amazon today. Consumers can use the GDRX discount card to fill online prescriptions with Amazon, and there is good reason why consumers might choose the GDRX discount card over the Prime discount program to fill the same prescription with Amazon Pharmacy: price. Amazon only works with Express Scripts - they have one PBM relationship. At the 2020 Barclays Global Technology conference, an ex-PillPack employee said GDRX has better cash prices than Amazon >90% of the time. The CEO of GDRX confirmed this and added that when Amazon beats GDRX on price, it’s typically by a small margin, but when GDRX beats Amazon, it’s often by a wide margin. Once again, we see the benefits that accrue from having multiple PBM relationships.

That dynamic could change if Amazon was the dominant mail-order player, and mail-order had a 90% share of prescriptions. With significant volume moving through their system, it’s not inconceivable that Amazon could bypass PBMs and go directly to manufacturers to secure better pricing. That could disadvantage GDRX, however it seems unlikely in the next 10-20 years.

Two Stanford professors completed a study last year on mail-order prescription prevalence in the U.S. from 1996-2018, and found that the channel has actually lost share over the last 10 years. Exhibit O shows two data sets. The graph on the left shows the percentage of respondents that have used mail-order at least once in a given year, and the graph on the right shows number of prescriptions ordered. If you multiply the two figures together, you can get total mail-order prescriptions, and the implication is that 7-9% of total prescriptions in the U.S. are filled by mail - and falling.

I would have expected that mail-order would take significant share during COVID, but that didn’t happen. Data from the IQVIA National Prescription Audit shows that the year-over-year change in mail and retail prescriptions in 2020 was more-or-less the same (Exhibit P). Considering the e-commerce uptick for most products, this is quite surprising.

So why hasn’t mail-order gained popularity? One reason is that >60% of mail-order prescriptions are delivered using the USPS, and delivery times are both long and unpredictable through that system. Amazon and some of these other emerging mail-order businesses should help address that problem, but even with free 2-day delivery, it’s often faster to fill prescriptions at a physical pharmacy. It will be challenging for Amazon to consistently reduce delivery times to 1-day or same-day, which would make it significantly more compelling.

Some other barriers are less addressable. For example, contraindication refers to a situation where one drug can be harmful if used in tandem with another drug or used on patients with multiple conditions. The pharmacist at the pharmacy counter is the last line of defense to prevent contraindication, and these physical interactions give consumers an opportunity to ask questions and contributes to peace-of-mind. This is way more important in healthcare than it is for run-of-the-mill consumer products, and is hard to replicate with mail-order pharmacy (although not impossible). In many patient surveys I’ve seen, another common concern is how mail-order might impact drug safety and efficacy. Lots of drugs require cold storage, and building out that specialty storage and transportation infrastructure is also challenging. Lastly, PBMs like Express Scripts actually prevent mail-order pharmacies from filling 90-day prescriptions. Moving from a 30-day to 90-day prescription can reduce the cost of Rx drugs for cash-paying customers, and this is a lever that many mail-order pharmacy discount programs can’t pull today.

I’m sure that mail-order pharmacy will be a much bigger part of the pie in 50 years than it is today, but it’s likely to be a slow and challenging journey. This isn’t a new concept, and there are good reasons that mail-order market share is no higher today than it was in 2006, even with the pandemic tailwind and Amazon entering the space in 2018. In the meantime, GDRX has mail-order options and a pricing advantage over all of their competitors (even the elephant in the room - Amazon), and it’s difficult to see that changing in a hurry. It’s worth noting that despite many of the concerns about competition from Amazon, I actually view Amazon has a more direct competitor to traditional pharmacies like CVS than GDRX.

Summing it Up

I compared Google search interest for GDRX relative to businesses in all three competitive categories (where possible), and the discrepancy is massive (Exhibit Q). Relative search interest for GDRX is greater than everyone else combined. This is clearly a reflection of competitive pricing, a high NPS, recurring users, traditional advertising scale (TV, etc.), and integration with EHR providers. In my view, this type of brand awareness and momentum is hard to derail, and scale should also allow GDRX to show up at the top of generic searches like “lowest price for Atorvastatin”. All told, I think GDRX is well positioned to remain a leader in this space for a long time, and I’d expect MAU growth to outpace competitors over the next decade.

Other Services

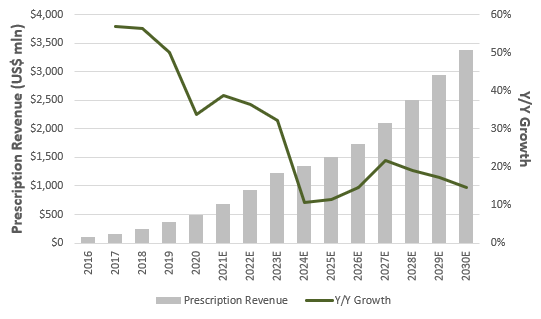

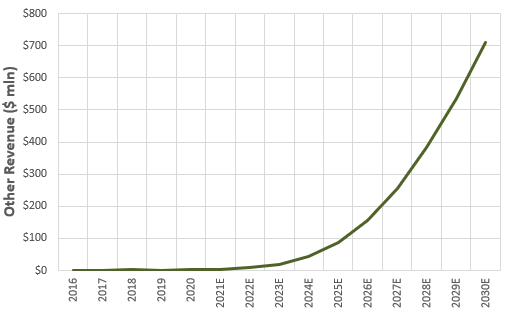

GDRX has purchased or built a number of additional businesses in the last four years, but lumps all of them into an “Other” line item. I’ve managed to piece together an approximate contribution by business from management commentary, which I’ve illustrated in Exhibit R. The primary takeaway is that these other businesses represented only 11% of 2020 revenue, but are growing much faster than the core prescription business.

Subscriptions

In addition to the free prescription service, GDRX offers two subscription services: GoodRx Gold (launched in 2017), and the Kroger Savings Plan (launched in 2018).

GoodRx Gold charges a monthly fee of $5.99 for individuals or $9.99 for families of up to five, and in return, subscribers get even cheaper prices on 1,000+ prescription drugs at participating pharmacies. According to GDRX:

“Some pharmacies offered us even lower prices if we could create a membership program for people filling 2 or more prescriptions at a smaller group of pharmacies“

As I understand it, the core GDRX prescription service receives pricing from PBM partners, whereas GoodRx Gold has negotiated prices with the actual pharmacies. I’ve seen no explicit mention of this, but it appears as if GDRX doesn’t get paid by PBMs for transactions through GoodRx Gold. Instead, they get to keep 100% of the subscription fees. They’re trading one revenue stream for another.

From the consumer perspective, the incremental annual Rx savings from GoodRx Gold needs to exceed $72/year for individuals and $120/year for families in order to breakeven on the subscription decision. For low-intensity Rx patients, this solution probably doesn’t make sense - they won’t save enough on the few prescriptions they fill. For patients with chronic conditions that require lots of ongoing prescriptions (particularly when it’s 2+ family members) the value proposition seems obvious. What’s also clear from looking through the medication list is that GoodRx Gold specifically saves more on popular generic drugs, but there are many drugs where the incremental savings are effectively nil (particularly branded drugs). So, GoodRx Gold can’t be all things to all people, but it has obvious value to some subset of patients.

The obvious question is why would pharmacies offer such competitive prices? First, relative to the core GDRX prescription, I believe that the pharmacy is saving on the PBM/GDRX fee, which might work out to 15-20% of GMV. Second, incremental savings on the subscription only apply to a subset of generics, where pharmacy markups are typically the highest, and the drug acquisition cost is typically low. The U&C profit margin might be 300%, but the profit in dollar terms might be relatively small. In theory, the pharmacy could cut the profit margin on the drug itself to zero, and make up the lost profit dollars by other purchases that come with foot traffic.

Independent pharmacies generate 90% of revenue from drug sales, but that number is much lower for big chains like CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Costco, and Safeway. These big-box stores typically put the pharmacy at the back of the store so consumers need to walk through aisles with other products on their way to the pharmacy counter. According to Ellis Management Consultants, every new script filled at pharmacies in grocery stores drives >$40 of additional sales in other departments. When I look through the list of participating pharmacies for GoodRx Gold, it’s clear that most are big-box stores that can generate front-end sales from pharmacy foot traffic, and it’s not surprising that the list includes no small independents. Clearly the profit from those front-end sales is expected to offset any lost profit from lower prescription drug pricing. This also explains why GoodRx Gold isn’t accepted at all big-box stores (like Walmart and Walgreens). If it was, it would dilute the benefit that participating pharmacies receive from that traffic. What’s also clear is that participating pharmacies specifically wanted to target “people filling 2 or more prescriptions”, and GoodRx Gold pricing is high enough that it likely only benefits recurring users = recurring foot traffic.

The GoodRx Gold model seems to disadvantage independents and PBMs to the benefit of select large pharmacy chains and consumers. It also benefits GDRX, who says that the gross profit from GoodRx Gold subscribers is roughly 2.0x higher during the first year of a subscription than the same user on the free prescription platform (gross margins are comparable to the core business). GDRX is also adding new services to GoodRx Gold like exclusive discounts on telehealth consultations. In the fullness of time I’d expect that this will start to look like more of a bundle with saving tools for other medical services like lab testing. This likely drives increased conversion from the free prescription platform, which contributes to gross profit growth.

In addition to the GoodRx Gold subscription, GDRX has also partnered with Kroger to offer the Kroger Savings plan. GDRX manages subscriber registration, consumer billing, transaction processing, and marketing, and clips part of the fee that Kroger charges in exchange. Unsurprisingly, the subscription fee for the Kroger Savings plan is lower than GoodRx Gold (fewer locations for consumers to choose from). As a result, the net fee earned by GDRX is much lower than on GoodRx Gold, and while participation seems to be strong to-date, I suspect this will remain a pretty small part of the business.

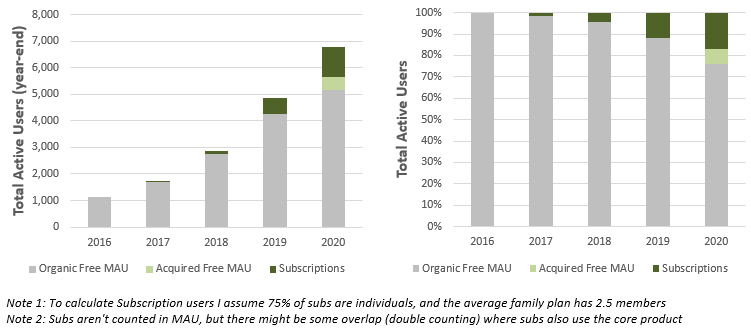

GDRX doesn’t include subscribers in their estimate of total MAU, which understates growth on the overall platform. Ignoring the acquired MAU from Scriptcycle, the trailing 4-year CAGR in organic MAU was 46%, but if we included subscribers in that estimate, the trailing 4-year CAGR would have been 56%. It’s not an apples-to-apples comparison to show MAU on the free prescription service versus total subscribers, but I show that comparison in Exhibit S anyway to illustrate that the subscription service is growing faster than the core prescription product.

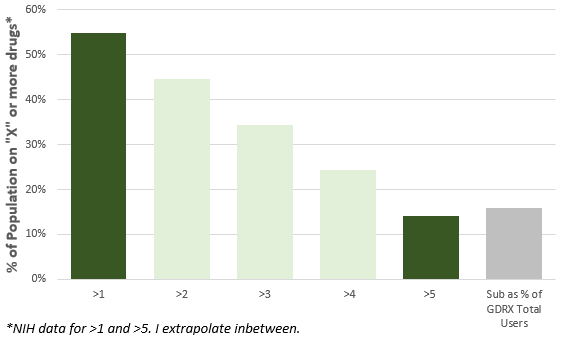

Many subscribers find GoodRx Gold organically, but GDRX also actively upsells to existing prescription users. Once a consumer has refilled a prescription several times under the free prescription service (the clear target market), GDRX prompts that recurring user to upgrade to GoodRx Gold, and conversion rates have clearly been quite high. Nevertheless, subscribers only made up 15% of total users in 2020. If we assume that the target consumer for GoodRx Gold is someone with two or more prescriptions, and that GoodRx Gold covered every drug, then penetration could reach 30-40% based on population data from the NIH (Exhibit T). In reality, GoodRx Gold isn’t exhaustive, so true steady-state penetration is probably lower than this. In any event, I expect the subscription business will grow much faster than the core product over the next 5+ years as penetration increases.

Telehealth

Telehealth is a natural extension of the Rx drug business, and because prescriptions originate with doctors, this is basically a vertical integration of those services. GDRX made their first foray into the space with the purchase of HeyDoctor in 2019, which has since been branded as GoodRx Care. They also launched a third-party telehealth marketplace in 2020.

GoodRx Care contracts with a network of on-demand physicians and affiliated professional entities to provide telehealth consults. GDRX has a purpose-build electronic health records (EHR) system that integrates with the GDRX prescription platform, and allows this physician network to video chat with patients and write prescriptions. By mid-2020, GoodRx Care consults covered 23 conditions in 50 states, and by the end of 2020 they had expanded to cover 35 conditions across 50 states.

This service is clearly geared toward cash-paying customers, which includes those with and without insurance. A JAMA Internal Medicine survey found that 25-35% of adults don’t have a primary care physician, and according to a Merritt Hawkins survey, the average wait time for a new patient appointment in the 15 largest metropolitan markets in the U.S. was 24 days in 2017. As a result, many insured patients without a GP might find it easier to use telehealth rather than wait to secure a GP visit or utilize traditional walk-in clinics. Even if you have insurance and a GP, the cost of telehealth consults is less than an office visit, so sometimes it’s competitive with insurance copay amounts, particularly for people on high-deductible health-plans or plans with high copays/coinsurance; not to mention, more convenient. This is especially true if you just need prescription refills.

According to GDRX, 20% of consumers don’t have a prescription at the time of their GoodRx search. I suspect that the primary strategic reason for the HeyDoctor acquisition was initially to cross-sell telehealth to those consumers (CAC on GoodRx Care consults would be nil). More recently, GDRX is advertising specifically for GoodRx Care, which should drive volume the other way. Apparently >10% of GoodRx Care consults lead to a consumer using a GoodRx discount code at a pharmacy. While 10% might seem low, it’s important to note that not all visits result in prescriptions, and that GDRX is in the early stages of integrating with EHR systems. In time, I think conversion will increase, and I basically view this as an alternative customer acquisition channel for the core prescription product.

Unfortunately, the telehealth space is really competitive, and physicians keep the vast majority of consult fees under the GDRX model. I estimate that gross margins are somewhere between 10-30% for GoodRx Care, which is significantly lower than the 90%+ gross margins generated by other GDRX businesses. When I factor in R&D, G&A, and S&M, GoodRx Care has most likely generated negative net margins in the past, even if I assume very little S&M is required for customers redirected through the core GoodRx prescription service. Given the low gross margins, this is clearly a business that requires scale to reduce the unit cost of R&D, G&A, and S&M. From inception in 2017 through the acquisition in 2019, HeyDoctor completed more than 100,000 consults (call it 10,000/quarter). GDRX reports that GoodRx Care consults jumped to ~100,000 in 2Q20 as COVID accelerated telehealth adoption. This certainly helped on the scale front, but it’s not clear how much of this shift is transient. In addition, I estimate that even if GoodRx Care consults grew to 250,000/quarter, they’d still be generating negative net income. To understand this better, it’s helpful to evaluate the largest telehealth provider in the space today: Teladoc.

Teladoc has >50% share in the telehealth space, and allows insured patients to use insurance on telehealth visits. In 2020, they facilitated more than 10 mln consults (versus GoodRx care at sub 500k), and generated average revenue/visit of greater than $100 (versus GoodRx care at ~$35-50). Exhibit U highlights a handful of very important things from the Teladoc financial statements. First, the average doctor fee per Teladoc visit over the last five years is $40, but they can charge a lot more because they accept insurance, which results in 65-75% gross margins. GoodRx Care targets cash-paying customers at a much lower price point, but the doctor fee should be similar, which explains why gross margins at GDRX are so much lower. In theory, GDRX could integrate with insurance providers, but this will be A) costly, and B) take time. Second, Teladoc wasn’t generating positive EBITDA margins until they had reached almost 3 mln annual visits, and even at 10 mln visits they only generate EBITDA margins of 12%. Expanding EBITDA margins were likely a direct result of scale across S&M, R&D, and G&A. Lastly, ignoring the doctor share (COGS), advertising and marketing spending is the single biggest cost item for Teladoc today. The majority of this spending is on digital advertising, which averages more than $20/visit.

Why is this Teladoc snapshot important? Well, I think it highlights that GoodRx Care is competing in a very low margin business that ultimately requires scale and integration with insurance providers, neither of which will be cheap or easy to achieve. They are also starting this race way behind some of the leading providers in the space. That’s the bad news. The good news is that even the most dominant telehealth provider is still dishing out $20 of ad spend per visit, and this presents a huge opportunity to GDRX.

I can’t prove it, but I suspect that the GDRX management team quickly realized that telehealth is a tough business, and trying to compete with just GoodRx care was going to be challenging, at best. So they looked to capture the telehealth opportunity in a different way. In steps the telehealth marketplace, dubbed GoodRx Marketplace.

The GoodRx Marketplace has partnered with more than 30 third-party telehealth providers, including the biggest competitors in the space like Teladoc. Many of these partners also accept commercial insurance and Medicaid. In total, these partners cover more than 150 conditions across 50 states, which is significantly more than GoodRx Care at 35. GDRX launched this service in March of 2020, and by the time the S-1 was released in August, they saw more than one million consumer visits to the marketplace and initiated more than 200,000 consults. With the limited data I have, it appears as if the GoodRx Marketplace is scaling much faster than GoodRx Care (which is also included in the marketplace search results).

GDRX generates referral fees for directing traffic to marketplace partners. In theory, GDRX could charge a partner like Teladoc a fee that’s consistent with how much they already spend on advertising/visit. For example, Teladoc ad spend is ~$20/visit, and if conversion for directed traffic was 100%, Teladoc would probably be amenable to paying close to $20/referral. In reality, conversion is <100%, and GDRX is probably aiming to be a competitive distribution channel for partners, so referral fees would be much less than this. I estimate that the average referral fee is somewhere in the $10 range, which would be more than the gross profit (fee/visit less doctor share) from GoodRx Care. I suspect that the cumulative R&D, G&A, and S&M for the marketplace business are less than GoodRx Care, which should result in much higher EBITDA margins, particularly as the marketplace grows.

The other way that GDRX generates revenue from the third-party marketplace is by integrating with the EHR systems of their partners to allow consumers to utilize the GoodRx prescription services if a prescription is written with the consult. This approach allows GDRX to move up the customer acquisition funnel to the point-of-prescription, and simultaneously lowers the customer acquisition cost while driving higher penetration for the core prescription business. In my view, a robust telehealth marketplace strengthens the companies competitive position in the Rx drug market.

McKinsey estimates that 20% of the 800+ mln annual doctor office visits can ultimately be addressed by telehealth, which works out to 160 mln annual doctor visits. Research from the department of healthcare policy at Harvard Medical School showed that annualized telehealth visits jumped to 156 mln during COVID, up from just 4 mln pre-COVID, which supports the McKinsey analysis. By design, a telehealth marketplace is optimizing for price, which means that recurring consumers will almost always be paired with a new physician - it’s unlikely that the marketplace facilitates recurring visits to the same physician, which means it probably isn’t suited to managing primary care. The CDC estimates that 55% of total visits are to primary care physicians, which means we need to adjust the 160 mln telehealth visits to include just those outside of the primary care market. Simplistically, this means that the addressable market for the GDRX telehealth platform is probably in the range of 65-75 mln visits (the required adjustments are definitely more nuanced than this, but it’s a reasonable ballpark). Finally, if we assume that 50% of visits in this category will be sourced through a marketplace, and 50% through a direct-to-consumer (or B2B) approach, then the true addressable market for the GoodRx Marketplace might be 35 mln patient visits. In 2020, GDRX had penetrated <2% of that market. If they knock execution out of the park on the GoodRx Marketplace, I wouldn’t be surprised to see telehealth revenue grow by more than 10x over the next decade (from a small base today).

Admittedly, I find it difficult to understand the growth potential of this business; my addressable market estimate could be off by an order of magnitude, and it’s not clear whether this will end up being a winner-take-most distribution channel or a hyper-competitive one. The Ever Given could easily navigate through my range of outcomes. That being said, the potential for telehealth growth is high, the GoodRx marketplace has shown early signs of significant progress, and penetration is still miniscule.

Pharma Solutions

There are only two countries in the world that allow for direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising (DTCPA): New Zealand and the United States. DTCPA was legalized in the United States in 1997, and a JAMA study shows that while total marketing spending for prescription drugs increased from $17.1 bln in 1997 to $26.9 bln in 2016, total DTCPA spending increased from $1.3 bln in 1997 to $6.5 bln in 2016 (7.5% of total to 22% of total). More recent estimates show that DTCPA is closer to $7.0 bln. The same JAMA study showed that most of this spending was geared toward television and magazine advertisements, with internet and mobile spending making up just 8% of total DTCPA in 2016.

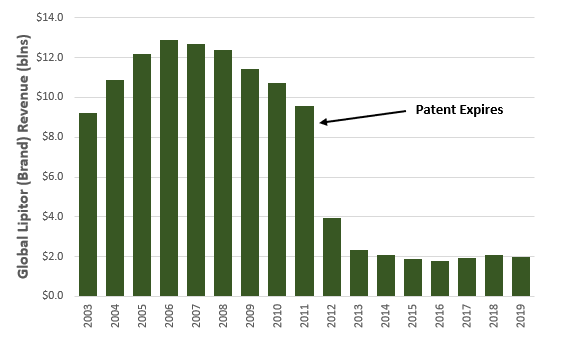

Most DTCPA is for branded drugs, and I think about the branded drug market as being two distinct groups: those where the patent has expired, and those that still have patents. When a patent expires, both price and volume of the branded product tend to fall significantly (but still be higher than the new generics), and Exhibit V shows what happened to global Lipitor revenue when the Pfizer patent expired in 2011. DTCPA for this cohort of drugs is geared toward defending market share. In my opinion, it doesn’t make sense for GDRX to build an advertising business around DTCPA for this cohort given their objective of promoting drug affordability (patients pay more for branded drugs than generic alternatives).

DTCPA for drugs that still have patents seems to be different. Many of these drugs are still very expensive, and advertising in this cohort is increasingly focused on raising awareness about coupons, rebates, or discounts to alleviate out-of-pocket patient spending. Many branded drug manufacturers offer patient assistance programs like co-pay cards. For example, Absorica is a branded drug used to treat acne that doesn’t have a generic alternative (it still has a patent). The U&C price of Absorica is ~$1,300 for a single fill. GDRX can reduce the cash price to ~$800, but Sun Pharma (the distributor for Cipher Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer) offers both a patient assistance program for uninsured consumers and a copay card program for insured consumers that can reduce the copay/coinsurance amount to just $25/fill. As I understand it, Sun Pharma discounts the out-of-pocket portion of the drug, and charges the insurance company/PBM the full rebated price for their share, which could be orders of magnitude higher.

GDRX has built a Pharmaceutical Manufacturer Solutions Offering which allows companies like Sun Pharma to advertise these patient assistance programs on the GDRX platform. When I search for Absorica, I see the full list of cash prices available with the GoodRx discount code, but also see a section detailing the Sun Pharma manufacturer coupon program. When I look at big pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer, advertising expenses are 5-7% of revenue. This is consistent with the JAMA study findings, which showed total pharmaceutical advertising spend was roughly 7% of total Rx revenue. If we assume that roughly 25% of this spending is DTCPA, then pharmaceutical companies might be willing to spend ~1.5% of revenue (GMV) facilitated through GDRX on advertisements in the platform, all else equal. Fortunately, all else isn’t equal. Pharmaceutical companies would likely spend more on ads for the GDRX platform then traditional TV or magazine advertising, so instead of advertising spend being 1.5% of GMV, maybe it’s 2.0-3.0%.

I have no way of really knowing what portion of GMV on the platform is for branded drugs with these patient assistance programs, but can make some guesses. While branded drugs represent just 10% of total prescriptions in the U.S., they make up roughly 75% of total revenue. GDRX indicates that their transaction mix is similar to the average. If I assume that 50% of the branded GMV moving through the GDRX platform could pursue DTCPA to alleviate out-of-pocket spending, then the maximum potential ad spending on the platform for 2020 would have been ~$40 mln ($3.4 bln of GMV x 75% x 50% x 3.0%).

I estimate that this advertising business probably generated $5-6 mln of revenue for GDRX in 2020, so while penetration is low and can probably go much higher, I don’t see this business becoming a meaningful driver of growth for GDRX in the context of 2020 prescription revenues of nearly $500 mln. It’s worth noting that gross margins on this revenue are likely >95%, which is comparable to the core prescription business, but that S&M/G&A/R&D would be proportionally much lower, resulting in higher EBITDA margins.

Other

“We believe there are many other areas of healthcare that could benefit from the transparency and accessibility provided by our platform. While we are currently focused on scaling our existing offerings, we see attractive opportunities to deploy our expertise in markets such as clinical trials, in person doctor visits and prescription delivery, among others. As we continue to grow our brand awareness and consumer base, selling additional products and services into our large acquired base will drive an attractive incremental margin opportunity“

Everywhere I look in the healthcare space I see room for improvement, and GDRX is clearly looking to build out new solutions outside of their existing offering. For example, they added lab tests to the telehealth marketplace (UTI, pregnancy, celiac, STD panels, allergies, etc.) and I suspect they’ll continue to add marketplace services in the next 12-24 months. It’s not inconceivable that GDRX starts to facilitate in-person visits for physiotherapy, optometry, and dentistry. They could also build out a marketplace for imaging (MRI, X-ray, Echocardiogram, etc.), where pricing can vary drastically. Apparently GDRX is even hiring for a VP of Strategy & Operations to lead something called MyCare, which might be the first step in expanding the marketplace into other medical verticals. Credit goes out (once again) to @AznWeng for sniping this (see thread). Historical expensed and capitalized spending on products and software show that GDRX meaningfully increased investments in the platform in 2020 (Exhibit W). In particular, the large increase in capitalized software development could be a leading indicator for new products.

GDRX is also hiring for a VP of Strategy & Operations to lead a rewards program called MyRewards. It’s not clear what this might look like, but this could be an effective way to drive direct repeat traffic to the GDRX platform, and reduce spend on performance marketing (like Google). If GDRX can help patients along any avenue of their medical journey (prescriptions, imaging, physician visits, dentistry, etc), and pair those services with a rewards program, it would be really hard for a competitor in just one niche to compete. The pricing, R&D, and S&M scale benefits from having a platform in every vertical would create massive barriers to entry. It might also let GDRX reduce their take-rate (improve pricing) but capture way more volume.

Risks

Healthcare Reform

The biggest risk to the GDRX model is healthcare reform, and that can come in many different shapes and sizes, so it’s worth exploring a few scenarios.

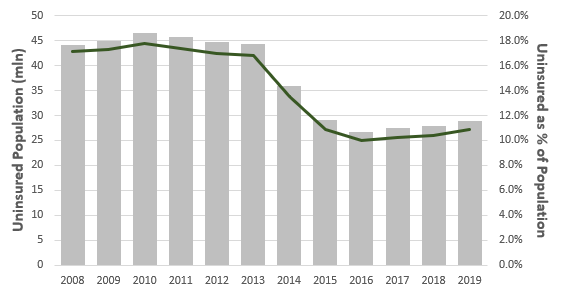

Major provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) came into effect in 2014, and helped millions of uninsured Americans access health insurance. From 2013 to 2016 the number of uninsured Americans fell by 40% (Exhibit X), which is unequivocally a good thing for those patients. Unfortunately for GDRX, this reduces the number of addressable high-ARPU consumers for the prescription platform. So even if all of those recently-insured patients could continue to utilize the GDRX platform, they’d likely spend significantly less in that channel.

Pre-ACA, adults were eligible for Medicaid if their income was lower than some threshold of the federal poverty line (FPL). The ACA increased the eligibility limit to 138% of the FPL, however the Supreme Court ruled that individual states could chose to continue at pre-ACA eligibility levels (which varied significantly, but tended to be lower). While most states increased the eligibility threshold, 14 decided not to (or only slightly increased it). In Exhibit Y I plot the eligibility threshold in 2020 versus the uninsured rate by state, and it’s clear that the uninsured rate is substantially higher in states that kept the threshold low. For example, the eligibility threshold in Texas is 17% of the FPL, and the uninsured rate is a whopping 18.4%. By my estimate, the national uninsured population would fall by another 7 mln people if all states were forced to increase the eligibility threshold to 138%. This single change could reduce the addressable GMV for GDRX by more than $10 bln (10%), and would most likely have a similar impact on ARPU. Of course, the opposite is also true. If the ACA is repealed, which I don’t see happening, many Americans could lose insurance and rely more heavily on GDRX.

There are other regulatory risks that seem like lower-probability but higher-consequence outcomes. I was shocked to find out that the U.S. government can negotiate drug pricing for Medicaid (low income patients) but not for Medicare (65+ patients). As mentioned earlier, NIH data shows that the national average rebate for commercial plans is 40-50%, while the rebate for Medicaid is closer to 80%. Medicare plans are run by private insurance companies (more fragmented), and most likely receive rebates in-line with commercial plans, which represents a massive affordability difference between Medicare and Medicaid. It’s therefore no surprise that Medicaid covers 20% of the U.S. population but makes up just 4% of GDRX MAU, while Medicare covers a similar portion of the population but makes up 34% of GDRX MAU. The fact that Medicare covers an older demographic also means that annual Rx spending per Medicare patient is also significantly higher than patients insured under Medicaid or commercial plans. If I had to hazard a guess, it seems fair to assume that Medicare users on the GDRX platform have disproportionately high ARPU relative to average.

Democrats and Republicans have both proposed different legislation that would lower drug prices for patients covered by Medicare. There are lots of different features in these proposals, but many of them would simultaneously lower the ceiling on out-of-pocket expenses and reduce drug prices for commonly prescribed medication. The Trump administration also tried to implement a reference-pricing rule for Medicare (Most Favored Nation) which would cap some prices at the lowest price a drug manufacturer receives in other comparable countries. Unfortunately, this type of policy change tends to get met with a litigation avalanche, and this was no exception. It’s not clear what changes to Medicare might eventually succeed, but it is clear that something is bound to change eventually. Any changes are likely to shrink the addressable market for GDRX, and have an immediate impact on ARPU and MAU.

It’s also possible that DTCPA gets increasingly regulated or abolished altogether. Many critics argue that pharmaceutical advertising indirectly results in higher Rx drug prices, and abolishing it would be an easy lever to pull for policy makers. The ad businesses isn’t a major contributor to the GDRX thesis, but is yet another example of regulatory/legislative risk.

The risks highlighted above are some of the known unknowns, but I’m confident that there are unknown unknowns as well. It’s always hard to predict this stuff. I can’t emphasize enough how susceptible the GDRX platform is to regulatory changes, which should be obvious given the fact that their business model wouldn’t make sense in other countries. It makes sense to bake some of these scenarios into the base case, but I also note how hard and slow it is to change anything in healthcare.

PBM Concentration

One oft-cited risk is that GDRX has PBM concentration, and if one or more PBM’s broke off their relationship it could impair the company’s pricing advantage. I’d note that the top 3 PBMs accounted for 42% of revenue in 2020, down from 61% in 2018. As the PBM network expands, this risk falls.

It’s also important to recognize that GDRX has never lost a PBM contract. The only reason that a PBM would consider leaving is if they could build a competing product and earn more operating income from their own initiative. As a GDRX partner, the PBM receives a revenue stream with operating margins of effectively 100%. If they built out their own competing product, they could capture much higher revenue/fill but also need to spend significantly on R&D, S&M, and G&A. They would also have to contend with execution risk, start with a meaningful scale disadvantage, and likely not be able to beat GDRX on price. As a result, I don’t see this as a meaningful risk to the business today.

Other

There are a few other risks worth highlighting:

Data privacy is a big deal when it comes to healthcare. There are plenty of federal and state regulations that are aimed at protecting patient data, and the consequences of stepping over that line the are huge. Directly, it could result in major fines. Indirectly, it could erode consumer trust, which would kill the brand. I don’t think GDRX would ever intentionally cross the line, but this is still a risk that’s unique to this type of healthcare business.

In the S-1, GDRX disclosed that their internal control and financial reporting processes were found to be deficient relative to standards required under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. They noted that: “we are in the very early stages of the costly and challenging process of compiling the system and processing documentation necessary to perform the evaluation needed to comply with Section 404(a) of Sarbanes-Oxley Act and we are taking steps to remediate the material weaknesses“. In 2020, they hired more accounting and IT personnel, updated procedures, and implemented a new ERP system. From the outside looking in, it appears as if they’ve addressed the deficiency, but in the unlikely event that they haven’t, it could result in restated financials.

I’ll once again circle back to Amazon. To be clear, I think Amazon is more of a competitor to brick-and-mortar pharmacies then it is of GDRX, but whenever a company like that steps into a space, it’s worth monitoring all the ripples they create.

Performance

GDRX went public in 2020, so we don’t exactly have a long history to evaluate. But, from the limited data available there are few things that stand out. Exhibit Z shows that revenue has grown exponentially (>50% CAGR since 2016). Even in 2020, when COVID negatively impacted physician visits (and therefore prescription fills), the top line grew at 42%. Despite this extraordinary growth, GDRX has consistently generated net margins in the mid-teens range. This goes to show how little incremental R&D and S&M is required to grow this business when you already have industry-leading scale, incredible brand awareness and a high NPS, and can easily roll out complementary products to an existing user base.

Management frequently touts an 8-month payback period on advertising spending, which contributes to high margins/growth. They calculate payback using gross profit in the denominator; however, if I assume that 50% of advertising spending is geared toward customer acquisition (growth), then the payback period using incremental run-rate EBIT has been more like 12-15 months, which is still great. According to GDRX, 70% of patients still don’t know that drug prices can vary by pharmacy, so most advertising is geared toward improving patient awareness. In my view, this represents lots of low-hanging fruit, and I expect that advertising payback periods will remain quite low over the next 5 years even as GDRX ramps up absolute spend, especially as they roll out new complimentary products.

While most of historical growth was driven by organic initiatives, GDRX has also completed two notable acquisitions: HeyDoctor was acquired for $14 mln in 2019, and ScriptCycle was acquired for $58 mln in 2020. It’s too early to provide a firm judgement on the success of these acquisitions, but the limited data I’ve found suggests that these were both probably accretive deals with long-term strategic value. HeyDoctor provided the company with first-hand knowledge of a complimentary vertical, while ScriptCycle added a new network of users with opportunities to cross-sell other services.

Reported ROIC went from 22% in 2018 to 39% in 2020, but I think it’s worth making a few adjustments. In particular, if I capitalize a portion of S&M and use adjusted NOPAT and invested capital figures, I get an adjusted ROIC of 16% in 2018 and 27% in 2020. Regardless of how I look at it, returns have been impressive and rising.

Financial Position

Pre-IPO, GDRX had nearly $700 mln of first lien debt, which was a whopping 4.4x 2019 EBITDA. Total proceeds from the IPO were roughly $900 mln, and by the end of 2020 GDRX had negative net debt of ~$300 mln ($969 mln of cash and $667 mln of debt). This business requires very little capital to grow, and over the last three years GDRX has consistently generated positive FCF after organic growth spending and acquisitions. As a result, it seems likely that most of those IPO proceeds will end up being used to pay down their debt. The First Lien Credit Agreement requires that quarterly principal payments are made through 2025, so it’s possible that they repay this debt slowly and deploy some of that cash balance on other initiatives in the meantime.

Management & Governance

Culture and Founder’s Mentality

GDRX was founded in 2011 by three partners: Doug Hirsch, one of the co-CEO’s; Trevor Bezdek, the other co-CEO; and Scott Marlette, who is still a shareholder, but has stepped back from the business and seems to be pursuing other initiatives. Doug and Scott worked together as early employees at Facebook, and Trevor was introduced to Doug through their mothers, of all places. It’s clear that the founders were friends first and business partners second, and Trevor and Doug still share an office. In an interview last year, Scott describes how GDRX came to be: the three friends had breakfast once a week for a year, with the specific intention of vetting business ideas. It sounds like they explored dozens, if not hundreds of ideas, until Doug proposed the concept for GDRX. I found an interview with Scott Marlette from early-2020 where he discusses the origins of GDRX (which you can watch here, starting at minute 34:00), and he made a great observation that I’ll summarize:

It’s great to start a business that solves a problem for you. That has two external benefits. One, you know it’s a problem that exists, because at least it’s a problem for one person. If you know it’s a problem for one person, it’s probably a problem for others. And two, you’ll be really interested and passionate about it.

From every interview and transcript I’ve digested, it’s clear that the founders are really passionate about solving the transparency and affordability problems in healthcare. As a result, they’re very customer and product focused, which explains why they didn’t just stop at Rx drugs; they find new problems and build products to address them, or find better ways to address the same problem and tweak the product. Scott was adamant that the product development philosophy at GDRX was centered around trial and error, where they shouldn’t be afraid to “move fast and break things” so long as they can also move fast to fix things. If they can do that successfully and maintain an entrepreneurial culture, then they can build and improve products much faster than many bureaucratic competitors in the healthcare space. In my view, the founders seem to have built a nimble, passionate, and customer-focused culture that has persisted over time. Glassdoor and Comparably ratings are easily top decile, and most employees post glowing reviews.