As always, if you have any pushback, comments, or questions I encourage you to reach out. You can comment below, find me on Twitter, or reach me at the10thmanbb@gmail.com. You can also find my DCF model below.

What problem does DaVita address?

The CDC estimates that roughly 35mn people have chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the U.S., which is roughly 1 in 7 adults. CKD has five stages, with Stage 5 indicating less than 15% kidney function – effectively full kidney failure. Only 2-3% of people with CKD end up progressing to full kidney failure, which is referred to as end stage renal disease (ESRD). Prior to COIVD, there were ~800k people living with ESRD in the U.S., and the ESRD population had grown by nearly 4%/year over the preceding two decades. Without intervention ESRD is fatal, and the only two treatment options are a kidney transplant or dialysis. Without question, kidney transplants are the preferred treatment option, but the supply of viable kidney organs falls way short of demand, and not all ESRD patients are even eligible for a transplant. As a result, only 30% of living ESRD patients have received a transplant. Everyone else relies on dialysis. Even for those that ultimately receive a transplant, the average wait is 3-4 years, and those lucky recipients still rely on dialysis to bridge the gap.

There are two types of dialysis; hemodialysis, where blood is pumped out of your body and through an artificial kidney machine to be filtered before returning to your body; and peritoneal dialysis, where blood and a cleansing fluid flow through the lining of your abdomen (often continuously). While peritoneal dialysis can be done at home – and is therefore significantly more convenient – hemodialysis is by far the most common method of treatment in the United States. Exhibit A shows the ESRD population in the U.S. broken out by method of treatment from 2000-2020 (public data post-2020 isn’t available yet).

In-center hemodialysis is clearly the dominant form of treatment for ESRD, and while transplants, home hemodialysis, and peritoneal dialysis have become slightly more prevalent over time, the treatment mix has hardly changed over the last two decades. And that’s where DaVita steps in. DaVita (DVA 0.00%↑) is one of the largest dialysis providers in the country and serves 200K patients from nearly 2,800 outpatient dialysis centers. While 80% of DVA’s dialysis revenue comes from in-center hemodialysis, they also use those centers to supports home dialysis patients and provide some dialysis services in hospitals.

Exhibit B shows DVA’s operating income by segment since 2000, and the U.S. Dialysis segment has historically been the only thing that matters. The Ancillary Services segment is mostly made up of DVA’s international dialysis business and their integrated care business called DaVita Integrated Kidney Care (IKC). Ancillary Services has historically generated negative operating income, but I think that’s set to turn positive over the next 2-3 years. I’ll expand on Ancillary Services later, but for now let’s focus on the U.S. Dialysis business.

U.S. Dialysis Business

The nuts and bolts of dialysis

Something like 30% of ESRD patients “crash” into dialysis. This likely means that these patients weren’t aware that they had CKD, their kidneys failed, and they ended up in the hospital where dialysis begins. For patients that regularly do check-ups, GPs will flag a kidney concern and refer those people to a nephrologist (kidney doctor). Nephrologists work with patients to manage CKD, and then manage the transition to dialysis if they expect kidney failure. Early nephrologist intervention leads to better health outcomes and a lower cost burden on the healthcare system, but once a patient ends up on dialysis, nephrologists almost always end up becoming the primary care physician (doesn’t matter if it’s planned or unplanned dialysis).

All outpatient dialysis centers are required to have a dedicated medical director to be eligible for Medicare reimbursement, where the medical director provides clinical oversight for a given facility and must be a credentialed nephrologist. There are ~11,000 nephrologists and ~7,700 outpatient dialysis centers in the country, so it’s safe to assume that the majority of nephrologists are also medical directors. DVA contracts with “900 individual physicians and physician groups” to provide medical director services, likely representing a few thousand individual nephrologists. DVA specifically stated in 2022 that they had relationships with 4,900 nephrologists that refer patients to their outpatient dialysis centers, which is something like 45% of all the nephrologists in the country!

Medical directors at DVA’s centers typically sign 10-year contracts at fixed compensation terms – they can’t legally get paid based on patient volume or center profitability. Those contracts have non-compete covenants and restrict the medical director from owning interests in dialysis centers operated by DVA’s competitors, but they don’t “prohibit the physicians from referring patients to any outpatient dialysis center, including dialysis centers operated by other providers”. Any one nephrologist might have 40-50 ESRD patients in their roster, and those patients won’t all go to the same dialysis center. So, the nephrologist rounds on patients anywhere that they have practice privileges. That could just be at multiple DVA centers, or include centers owned by DVA’s competitors. From the patient perspective, convenience plays a big role in deciding where to receive dialysis, but all else equal, I suspect nephrologists are biased to recommend dialysis centers where they work (or hold medical director roles) and already treat multiple patients – from the nephrologist perspective there is a familiarity and convenience factor that would drive this preference. In my opinion, DVA’s medical director relationships help fend off competition, particularly from new entrants who may look to steal dialysis patients. It’s also important to recognize that almost 30% of DVA’s U.S. Dialysis revenue comes from joint ventures where DVA has a controlling interest. Those joint ventures often have nephrologists as minority investors, and those specific nephrologists obviously have a very strong incentive to make sure their patients receive dialysis at their centers. As the primary care physician, they’re well positioned to make that happen. In my view, the easiest way to think about this is to frame the nephrologist as the top-of-funnel for dialysis patients, and DVA’s medical director contracts help secure a very wide top-of-funnel. The same could be said for Fresenius or other large multi-center networks, but in general I think this creates some barriers to scale for new entrants.

Once an ESRD patient selects a dialysis center, they typically come in 3 days a week for dialysis treatments. Dialysis centers are outfitted with multiple dialysis stations/machines (usually installed in increments of 4 because of some weird logistical nuances), and increasingly have training centers for patients that choose to receive dialysis at home. On average, each DVA dialysis center supports about 75 patients (both in-center and at home), where ~25% of patients turn over every year because of mortality and transplant selection and get replaced with new ESRD patients.

This is simultaneously a labor- and capital-intensive business. Roughly a third of operating cash flow is spent replacing expensive dialysis machines and completing leasehold improvements ($200-300k/center/year). DVA also employs 20-25 “teammates” per center, with registered nurses, patient care technicians, dietitians, and other support/admin staff. That works out to roughly 1 employee per 3 patients. Layer in the cost of treatment and related drugs, and next thing you know DVA’s total cost to provide dialysis services works out to ~$45k/patient/year! I’ll get into the payor dynamics later, but this is such an expensive treatment that people with kidney failure represent 7% of the Medicare budget but just 1% of the Medicare population. Despite this extraordinary cost, there’s sadly no substitution for dialysis outside of transplants, and transplant demand has perpetually exceeded transplant supply.

DVA Market Share and Patient/Treatment Growth

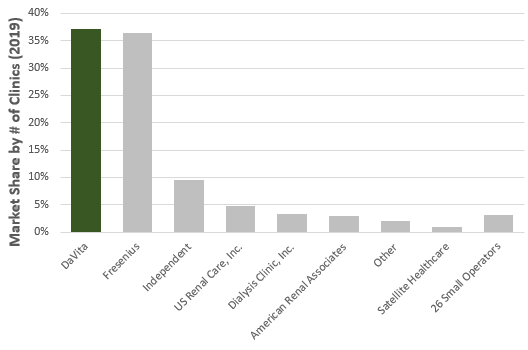

DVA was founded in 1979 and went public in 1995. Through a combination of organic expansion and M&A, DVA has since grown to become the largest dialysis provider in the United States, with a 2022 market share of ~37% (measured on both centers and patients). That’s up from sub-10% when they IPO’d.

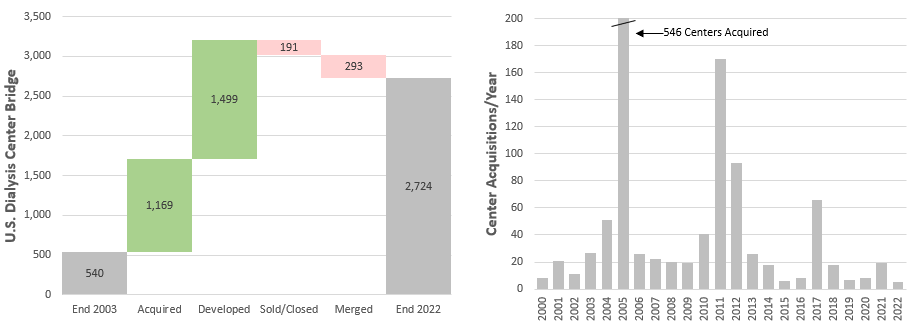

Exhibit D shows the contributors/detractors of DVA’s dialysis center growth between 2003 (when they started reporting this data) and 2022. It also shows center acquisitions/year. While organic expansion was an important part of their story, DVA actually acquired 40%+ of their current center footprint. If you ignore 2-3 big acquisitions, DVA acquired ~20-25 centers/year at an average price of just $3-10mn/center – often through multiple transactions each year. Section 7A of the Clayton Act requires that acquisitions must be reported to the DOJ and FTC if they exceed a certain size threshold, and one reason for this is to prevent industries from extreme consolidation which could lead to anticompetitive market dynamics. That reporting threshold was $15mn in 2000, and now sits a little over $100mn. Since DVA made so many small acquisitions, they effectively flew under the radar of the DOJ and FTC and were able to acquire their way to a dominant market position without much resistance.

There aren’t as many dialysis centers left to be acquired any more, so it looks like continued consolidation will be challenging. For the few remaining targets, there are also new FTC restrictions that might prevent DVA from stepping in, even if the transaction size was below the reporting threshold. For example, in 2021 the FTC ruled that DVA can’t acquire “any new ownership interest in a dialysis center anywhere in Utah for a period of ten years” without prior approval from the FTC. Not one center. This order came in response to a proposed DVA acquisition in an already concentrated market (apparently there are only three dialysis providers in the greater Provo, Utah area where DVA was looking to acquire). For both reasons, I think DVA’s consolidation strategy is coming to an end, if it hasn’t already. But at this point, it’s too little too late… they’ve already locked down more than a third of the national market.

DVA wasn’t the only business to consolidate U.S. dialysis centers. A German healthcare company called Fresenius Medical Care pursued a similar strategy, and currently controls another ~36% of the U.S. dialysis market. Together, these two behemoths hold a whopping 73% market share (Exhibit E). The rest of the market is fragmented, with about 30 small multi-center operators (15% share), 700-750 independent centers (10% share), and various state-owned and not-for-profit centers to round it out (2% share).

Exhibit F shows DVA’s U.S. Dialysis treatment growth broken out by organic vs. M&A contributions since 2000 and compares that to industry patient growth (a proxy for treatment growth). Organic growth has only been slightly better than overall industry growth, so most of the share gains at DVA over the last twenty years were a function of consolidating smaller center networks. With that consolidation theme running out of steam, I think it’s reasonable to expect that DVA patient and treatment levels will start to ebb and flow more closely with the industry - that is to say, organic growth and industry growth are likely to be very similar.

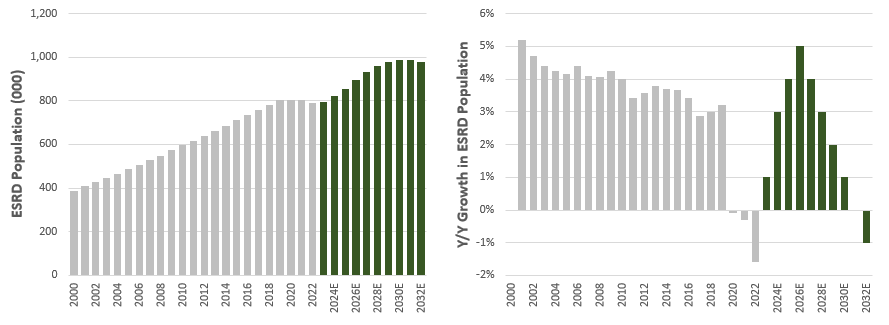

Prior to COVID, the ESRD patient population and the dialysis population had grown at a 20Y CAGR of 3.7% and 3.5% respectively – much faster than overall population growth. ESRD prevalence has increased (Exhibit G), and that’s been a huge tailwind for the likes of DVA and Fresenius. As such, it’s important to understand why the ESRD population grew so much faster than total population growth, and whether that should continue.

The leading risk-factor for ESRD is diabetes, and the leading risk factor for diabetes is obesity. I suspect it surprises exactly 0% of readers when I say that that obesity rates have steadily increased in the United States. In the last twenty years alone, obesity prevalence in the adult population has gone from 30% to roughly 42%. Severe obesity prevalence has gone from ~5% to ~10%. Obesity rates in the U.S. are substantially higher than almost anywhere else in the world. For example, obesity prevalence in Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom, and Germany are just 29%, 29%, 28%, and 22% respectively – that’s a far cry from 42% in the United States. As a result, the United States has the second highest ESRD incidence rate in the world according to NIH data (Exhibit H; I have absolutely no idea why Taiwan was such an outlier in this NIH data).

The consensus seems to be that the U.S. obesity rate will continue to climb over time. A New England Journal of Medicine study (link) from 2019 estimated that adult obesity rates would be ~49% by 2030, and that the severe obesity rate would increase to 24%! I found similar studies that pegged 2030 obesity rates around 50%. Against that backdrop, I think it’s reasonably likely that ESRD prevalence will continue to increase for the foreseeable future, which should contribute to ESRD patient growth in the 2-4% range, all else equal. If you assume that DVA market share stayed flat, then a reasonable expectation might be 2-4% patient and treatment growth for DVA from 2019-2030.

COVID obviously had a negative impact on dialysis treatments, primarily because of excess mortality in the ESRD population and missed treatments. DVA’s U.S. dialysis patient population was down by 3.5% from 2019-2022 and total treatments were down by about 4.0%. As I’ve shown in Exhibit F, this was the first time ever that DVA realized negative organic treatment and patient growth. In my view, this was a temporary reduction in the ESRD population, and eventually the cumulative impact of excess mortality will normalize. I have no idea if this will take 2 years or 6 years but feel reasonably confident that it will occur. DVA’s management team specifically calls this out as a near-term tailwind to growth through 2025/2026 if you use 2022 as the starting point. If we assumed that the ESRD population would have grown at 2.0-4.0% from 2019-2030, and that the impact of excess mortality will normalize, then it would be fair to underwrite 3.0-5.5% ESRD patient and treatment growth from 2022-2030. If the dialysis/transplant mix stayed constant, and no new medical intervention was introduced that prevented ESRD, this would be a good proxy for DVA volume growth.

Eventually you’d expect that obesity and other risk factor rates would stabilize. When that happens, the ESRD population should just track total population growth, which is likely to be sub-1%. But given most of the trends I’ve observed, I’d guess that this deceleration is more than a decade out.

In my view, the medium-term range of outcomes from a treatment and patient perspective is relatively narrow if you don’t expect any breakthroughs in ESRD prevention and treatment – and there hasn’t been anything meaningful for decades. Longer term there are plenty of reasons that ESRD prevalence and demand for dialysis could decline, even in the face of higher obesity rates. I’ll circle back on some of these risks later, but by and large these appear to be risks that might not manifest in any meaningful way for a decade, or longer.

The Unusual Economics of U.S. Dialysis

Most people are only eligible to sign up for Medicare when they turn 65 years old, but there are two medical conditions that Medicare will cover for anybody regardless of age: ESRD and ALS. ESRD has been covered by Medicare since 1972, but there are still some unique eligibility and coverage nuances. I’ve detailed the most relevant below:

For patients that already have health insurance through an employer (or spouse’s employer), that commercial plan becomes the primary payor for the first 30 months after dialysis begins. After 30 months, Medicare takes over as the primary payor, and the employer health plan pays second. There is a unique rule based on the Medicare Secondary Payer Act (MSPA) that effectively forces commercial insurance to take the primary payor role for the first 30 months, although there is a loophole that just cropped up – but I’ll touch on that later.

Once a patient becomes eligible for Medicare, there is a 3-month waiting period before Medicare becomes the primary payor, but only if the patient chooses in-center hemodialysis. For dialysis started at home or kidney transplants, Medicare coverage begins immediately.

Medicare only covers 80% of each covered dialysis treatment. The remaining 20% is covered by the patient, although secondary payors like a commercial health plan, supplemental insurance, Medicaid, or charitable organizations typically cover the balance. According to DVA, less than 1% of their U.S. Dialysis revenue ends up being due directly from patients.

Some patients are covered by Medicaid and other government programs, but most people living with ESRD are either covered by Medicare (or Medicare Advantage) immediately given that the average age of ESRD patients is ~65, or have Medicare kick in after 33 months of commercial coverage (30 months plus the 3-month wait period). Exhibit I shows DVA’s patient split by primary payor since 2000. M&A has changed DVA’s payor mix a little over time, but in recent years patients covered by commercial plans have only represented 10-12% of the total patient mix.

Now for the wild part. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) sets the dialysis reimbursement rate for all patients covered by Medicare and Medicaid, and for whatever reason they’ve set that reimbursement rate below the actual cost to provide dialysis services. When I run the numbers, it looks like DVA actually loses $4,000-5,000/year/patient on average for those covered by a government program (largely Medicare and Medicare Advantage). The only reason that DVA and other dialysis providers make money is because they charge commercial payors 4x more for dialysis services. Exhibit J shows DVA’s revenue/patient under three different payor categories vs average opex/patient and implied operating income/patient. Even though commercial payors represent just 10% of patients they’re responsible for 33% of revenue and more than 100% of segment operating income.

Medicare Advantage (MA) typically pays DVA more than the regular Medicare fee-for-service model, and more patients are shifting to Medicare Advantage. That should help reduce the reported loss/patient for the aggregate Medicare/MA pool. Even still, commercial payors are basically subsidizing the government – without commercial payors footing that bill, none of these dialysis centers could exist at the current CMS reimbursement rates. If you recall from one of my earlier comments – ESRD patients represent just 1% of the Medicare population but 7% of the budget. CMS clearly has every incentive not to bear a greater burden of the ESRD treatment cost, and the Medicare Secondary Payor Act (MSPA) is set up such that commercial payors should be forced to perpetually foot a disproportionate part of the bill. In fact, when I compare operating income (loss) per patient/year for commercial payors vs aggregate government payors over time (Exhibit K), we can see that the average operating loss from government payors has remained relatively stable while the average operating income from commercial payors has increased substantially.

While CMS rates are non-negotiable, DVA negotiates rates with commercial payors. Historically, they’ve been very successful at negotiating rates that allow them to earn exceptional returns on capital. And that brings us to their competitive position.

U.S. Dialysis Competitive Position

While the two largest dialysis providers have locked down 70%+ of the dialysis market, the commercial insurance market is much more fragmented. The largest insurer has 15% market share (less than half what DVA enjoys), the top 5 insurers control just 50% of the market, and there is a very long tail of small competitors. So, when it comes to dialysis, the balance of power sits with DVA and Fresenius. That’s the beauty of a duopoly.

One reason DVA and Fresenius have so much market power is that insurers wouldn’t be able to provide adequate in-network coverage without their centers. Up until two years ago, there were rules that required plans meet specific time and distance standards to qualify as having an adequate network – it would be nearly impossible for any large plan to meet those requirements if they didn’t have both DVA and Fresenius in their network. That rule changed, and now plans just need to self-attest that they have an adequate network, but the same principal applies. In a Tegus interview last year the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) from Humana noted:

“If you were to map out all these dialysis centers, you’ll find there’s a few areas where there’s not a ton of overlap [between DVA and Fresenius], where you need one in certain areas. And that’s where you get really stuck because it’s very hard to just have one provider if you’re a national player”

So, it’s not like a national player could even just pick one of the two dominant providers – they need both. Because national plans (which cover most commercial payors) need to contract with both DVA and Fresenius, those two large providers can charge a premium over the long tail of small dialysis providers, and a massive premium over Medicare/Medicaid – it’s very much a take-it-or-leave-it proposition:

“Usually, the smaller providers, you don’t really need them. You could potentially go to the smaller providers and say give us a lower rate…. but they need us more than we need them”

“So the way they frame this [DVA and Fresenius], and they’ve been really successful, is that these are our costs. This is what dialysis cost. If you sign a deal with us, you’ll have nationwide access for your plan, and you probably won’t have to worry about dialysis. Because you could say no and try and find individual fragmented players, but that’s just a lot of work… and if you’re a commercial player, you’re worried about retention.”

The CMO went on to explain that Humana was very cognizant of member complaints. If they dropped DVA centers, then a bunch of their plan members could end up having to switch nephrologists or travel long distances to receive dialysis. That would certainly lead to social media backlash and complaints to CMS, which in turn could lead to fines or lost market share, even if the plan argued that they still provided adequate coverage with home dialysis combined with a smaller in-network footprint. Ultimately, the CMO’s view was that the downside from trying to cut out either DVA or Fresenius was just too high.

That’s not to say DVA and Fresenius have free range to charge whatever they want. Technically there is still competition from independents and smaller multi-center operators, and there is some price where a national commercial customer would drop DVA and deal with the backlash and headache of contracting with those providers and working out better home-dialysis coverage. There are also states where DVA has <20% share and Fresenius has >60% share– if they went to a regional commercial customer who only cares about coverage in one of those states and asked for a 50% increase in rates, that regional commercial customer could probably get away with just dropping DVA from their network and leaning on Fresenius and other competitors.

It’s also worth noting that DVA and Fresenius likely have a scale advantage over other competitors that ultimately translates into lower unit costs per dialysis treatment. For example, both DVA and Fresenius have contracts with Amgen to supply Epogen or a comparable product (drugs used to control anemia in dialysis patients), and both contracts provide for discounts and rebates that small competitors would not enjoy. The large providers also benefit from centralized clinical laboratories, spreading fixed costs of medical record systems across more patients, and better utilization. In my view, DVA and Fresenius have almost definitely reduced the per unit cost of dialysis treatment vs the unit cost of small providers and independents – although it’s hard to prove definitively. To test that thesis, I looked at opex/treatment since 2000 alongside DVA market share (Exhibit L). Since DVA reached 30%+ share in 2006, there has been almost no nominal increase in opex/treatment. In real terms, opex/treatment fell 24% from 2006-2022. I haven’t been able to find data on opex/treatment for small providers, but I have to imagine it hasn’t stayed flat for 16 years. If I’m right that DVA and Fresenius have a cost advantage, it would make it challenging for other competitors to price substantially below them. In other words, DVA and Fresenius can enjoy significantly higher margins than other providers with even a modest premium over small provider rates.

In my view, DVA and Fresenius have effectively negotiated some baseline premium to Medicare rates, and the best strategy is to maintain the status quo. They’re likely to realize inflation-linked rate growth, and not rock the boat with any of their commercial payors – whatever pricing power they have has likely already been exercised. And that’s fine, because current pricing combined with what is most likely an advantageous cost structure has led to exceptional returns – by my estimate they are generating a 25-30% ROIC from their U.S. dialysis businesses (stripping out goodwill, which better reflects the run-rate profitability of the underlying business).

Recent volume and margin headwinds should be in the rearview mirror

Exhibit M shows operating income/patient/year, operating margins, and total adjusted operating income (stripping out legal settlements) for the U.S. dialysis business since 2000. The per/patient and margin KPIs have been pretty consistent through time but deteriorated significantly in 2022 and are now at-or-below the bottom end of the T20Y range. Operating income/patient/year fell by 19% in 2022, and segment operating income in absolute dollars fell by 21%!

One contributing factor is a decline in patient and treatment volumes on the back of excess COVID-related mortality that I outlined earlier. This led to a slight reduction in patient and treatment volume per dialysis center, and some margin compression on the back of that lower utilization/fixed-cost deleveraging – not to mention the revenue headwind. Exhibit N shows that DVA’s treatment volumes declined when COVID started and excess mortality spiked. Excess mortality has largely normalized, and 1Q23 was the first quarter since 2Q20 where y/y treatment growth was positive. Weekly CDC data actually shows no excess mortality QTD for 2Q23, although they acknowledge there is a wide margin of error. Even still, it looks like the negative impact of COVID on treatment volumes is behind us, and I’d expect that patient and treatment volume growth will be positive for 2023+. DVA has also closed some low-utilization centers and directed those patients to other DVA locations to help combat the fixed-cost deleveraging problem, which should contribute to better operating income/patient for 2023+.

The other big challenge that everyone in industry has grappled with over the last 12-18 months is a skilled labor shortage and labor inflation. As I mentioned earlier, DVA has roughly 1 employee for every 3 patient’s that they treat, so labor inflation can quickly eat into margins if dialysis rates don’t adjust in tandem. And that’s exactly what happened in 2022.

On the labor side there were two challenges. First, DVA calls out a nursing shortage that contributed to elevated teammate turnover in 2022 which “led to increase training and onboarding costs and costs related to contract labor”. As I understand it, part of that shortage is a function of “COVID burnout” – healthcare professionals took a heavy toll during COVID, and some had left to pursue other professions. DVA then has to hire new people and go through the onboarding/training process. New staff tend to have lower productivity, and DVA noted that clinical hours/treatment increased in 2022 as a result. It looks like some of these challenges have abated over the last two quarters and margins are starting to stabilize/improve.

The second challenge is good ol’ fashioned wage inflation. DVA’s clinical labor rates inflated at 3.9% in 2021 and 7.4% in 2022. That’s a rapid increase in one of DVA’s largest expense line items. At the same time, there is a lag between operating cost inflation and revenue/treatment inflation. For example, Medicare treatment rates only increased by 0.2% in 2022 (recall from Exhibit K that operating loss/patient/year for aggregate government payors in 2022 was a clear outlier). Medicare increases base rates every year in-part based on provider cost inflation, and it looks like new Medicare base rates are already starting to reflect these inflationary forces, so I’d expect to see the operating loss/treatment normalize. On the commercial side, DVA typically signs 3-year contracts with some pre-negotiated rate inflators built in based on their expectations for inflation at the time. As a result, it can take 2-3 years for commercial rates to fully reflect a rapid change in inflation, although commercial treatment rates did increase by 4.8% in 2022 – more than Medicare, but less than opex/treatment inflation of 6.3%. With new Medicare rates and more commercial contracts rolling over, I think it’s reasonable to expect that margins will improve in 2023/2024 vs the trough in 2022. Exhibit O shows that margins have already stabilized and seem to be improving as of 1Q23.

In my view, it’s more a matter of when not if treatment volumes and margins normalize, and when that happens, I think DVA’s U.S. Dialysis business can generate something close to $2.0bn in operating profit ever year. As I’ll elaborate on later, I think the market initially discounted this normalization but is most likely pricing in the full $2.0bn of operating income today. Even though I think the market is now giving DVA credit for $2.0bn of U.S. Dialysis operating income, not a lot of growth from there seems to be baked into the current share price. That tells me that the market is pricing in some other risk – and there are plenty of risks to think through, which I’ll touch on next.

U.S. Dialysis Risks

I’ve given this considerable thought and have identified six risks that I think a DVA investor needs to grapple with. If you’re reading this and feel like I’ve missed something, please feel free to reach out directly or comment at the end of this post. I walk through each of these concerns below.

Risk #1 – Mix shift from commercial payors to Medicare

Commercial payors have consistently represented 10-11% of DVA’s patient mix over the last 10+ years. All else equal, for every 1% change in the commercial payor mix, I estimate that DVA’s segment operating income would change by a little less than $200mn or roughly 10% of normalized operating income.

Given the high cost of dialysis treatment – particularly for commercial payors – it’s no surprise that some commercial payors would look for a way to shift ESRD coverage responsibilities to Medicare. This has long been a risk, but a recent Supreme Court decision opened the door for some plans to do exactly that, and it’s worth covering what happened and the potential implications for DVA.

In 2018, DVA sued the Marietta Memorial Hospital Employee Health Benefit Plan (“Marietta”) for what they viewed as a violation of the Medicare Secondary Payer Act (MSPA). Under the MSPA, there are two relevant constraints to prevent commercial plans from “circumventing their primary-payer obligation for end-stage renal disease treatment” (the obligatory 30-month coverage period):

A plan “may not differentiate in the benefits it provides between individuals having end stage renal disease and other individuals covered by such plan on the basis of the existence of end stage renal disease, the need for renal dialysis, or in any other manner”

A plan “may not take into account that an individual is entitled to or eligible for Medicare due to end-stage renal disease”

In plain English, commercial plans can’t discriminate between ESRD patients and other members by denying reasonable ESRD coverage, which in turn would push those patients onto Medicare. It’s a very nuanced case, but as I understand it Marietta provided such limited outpatient dialysis coverage that patients remaining on the Marietta health plan would foot something like 60-70% of the dialysis bill. In turn, those patients would be forced off the Marietta health plan and onto Medicare. If you interpret the MSPA broadly, that seems to be a clear violation. Marietta argued that they weren’t differentiating between individuals with ESRD and those without, because they were just limiting outpatient dialysis coverage vs other ESRD treatments. They go on to argue that outpatient dialysis isn’t a proxy for ESRD even though 97% of patients diagnosed with ESRD require dialysis and 99.5% of DVA’s outpatient dialysis patients have or develop ESRD. If I had read the initial arguments before courts weighed in, I would have said with 90% certainty that DVA would win in this case. Turns out I’d make for a bad lawyer.

DVA’s claims were initially dismissed in court. DVA then appealed, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed the first ruling and sided with DVA. The Court of Appeals concluded that Marietta had violated the MSPA constraints, but it wasn’t a unanimous decision. The case was then sent to the Supreme Court who released a decision in mid-2022 and sided with Marietta – they concluded that Marietta hadn’t violated either of the MSPA constraints. If you’re interested in the Supreme Court ruling, you can find it here (link).

As a layman reading through the relevant issues and decisions, it strikes me that there is a big difference between a narrow interpretation of the letter of the MSPA and the intent of the MSPA. When Congress enacted the MSPA they intended to prevent exactly what Marietta is doing. Two of the Supreme Court Justices filed an opinion dissenting in part that you can find at the bottom of the ruling I linked above. One of those Justices - Justice Kagan – provided this closing statement in her dissenting opinion (emphasis my own):

“As the majority recognizes, the MSPA’s renal disease provisions were designed to prevent plans from foisting the cost of dialysis onto Medicare. See ante, at 2. Yet the Court now tells plans they can do just that, so long as they target dialysis, rather than the patients who rely on it, for disfavored coverage. Congress would not—and did not—craft a statute permitting such a maneuver. Now Congress will have to fix a statute this Court has broken. I respectfully dissent.”

This was such an important outcome that DVA’s share price fell 15% the day the Supreme Court decision was announced. Without Congress’ intervention it looked like certain commercial plans could shift their primary payor responsibility to Medicare – this was a bigger risk for small plans vs large insurers and employee groups because of other barriers applicable to larger plans. I’ve seen estimates that 10-15% of DVA’s commercial segment consisted of small plans that could take advantage of the Marietta ruling. If most those plans forced ESRD patients into Medicare, then DVA’s operating income might fall by ~$200mn. That would be a 13% reduction in T5Y average total operating income (once we factor in corporate costs and the other segments). Against that backdrop, the Day 1 market reaction seemed pretty fair, if not just a tad punitive.

But then a couple months after the Supreme Court decision, the Restore Protections for Dialysis Patients Act was introduced to Congress, and it now has over 40 co-sponsors from both sides of the aisle. As we sit here in mid-2023, it looks incredibly likely that Congress will eventually intervene and change the MSPA language such that this loophole no longer exists - exactly what Justice Kagan suggested. In the meantime, I’ve seen no evidence that the commercial payor mix has declined meaningfully. Crisis (likely) averted.

Despite what is likely to end up being a nothing-burger, I flagged the Marietta saga to illustrate that A) some commercial payors would love to pass the buck, and B) the financial implications if they are successful can be significant. As I think about the risk of a lower commercial mix, I’d classify it as a known unknown. You know it’s a risk, but it’s very hard to predict how it will rear its ugly head and what mitigating factors might exist. Over any long period of time, DVA investors should expect issues like this to crop up again. Even still, there is clearly significant bipartisan support to prevent commercial payors from shifting coverage responsibilities to Medicare, and I don’t see that changing – if new loopholes pop up, Congress should be there to close them. As a result, I’m not that concerned about a meaningful reduction in the commercial payor mix.

Risk #2 – Legal charges

DVA has paid a little more than $1.0bn in settlements and legal charges over the last ten years, which works out to ~10% of total FCF over that period – not a small number. Cumulatively, I’ve counted 19 different civil suits, investigations, and other litigation. Of the 13 incidents that have already concluded, there was no material adverse impact to DVA from most of them, but two cases in particular were responsible for ~80% of the total settlements they’ve paid over the last decade. In one of those two cases, DVA settled a suit concerning fraudulent overbilling for certain drugs from 2003-2008. In the other case, DVA was sued for improper risk adjustment submissions and payments at one of their subsidiaries from 2008-2013. In that instance, DVA had purchased a business who had improperly charged CMS before DVA acquired them – as part of the acquisition agreement, DVA had held back a portion of the purchase price as security for indemnification rights, and the $270mn of settlement payments for the case was paid out of that holdback.

There are currently 5 outstanding government inquiries and 1 outstanding civil suit that have uncertain outcomes, for a total of 6 outstanding matters. Of the 13 settled matters, 2 resulted in huge settlement payments, although technically DVA was aware of the issue they settled for $270mn and didn’t foot that bill. Even still, let’s call that a 16% base rate for negative outcomes from civil suits and government investigations. So, of the 6 outstanding matters, let’s say 1 of those ends up being a $500mn settlement. Over the course of a decade, that’s $50mn/year in settlement fees. Personally, I’d bake that into my model for valuation purposes.

As I’ll get to later, DVA is very focused on doing the right thing – they seem to care a lot about employees (who they call teammates), patients, and partners in the ecosystem. I’m confident that no executives intend to get into legal trouble. Unfortunately, if you have 37% market share with tens of thousands of employees and thousand of centers, and operate in an imperfect but very important industry, you’re bound to step over some lines inadvertently – that’s especially true in the for-profit healthcare space. DVA isn’t alone here – Fresenius has faced similar legal challenges. In my view, that’s jut the cost of doing business in the dialysis space at this scale, particularly in a very litigious country. Again, I think this is a known unknown, and DVA investors should bake some future settlements into their financial expectations.

Risk #3 – The shift to home dialysis

DVA’s entire business is built around outpatient dialysis centers. They have more than $8.0bn of gross capital tied up in these sites. One perceived risk is that if more patients choose to receive dialysis at home (either home hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) it would decrease utilization of DVA’s center network and lead to lower margins. It could also open the door for new competitors that don’t currently have a physical center network to try and compete for those patients. Finally, even if DVA keeps those customers under their care, I’ve seen some concern that home dialysis economics are worse than in-center economics. I’ll circle back to each of these points after quickly providing the lay of the land on home dialysis.

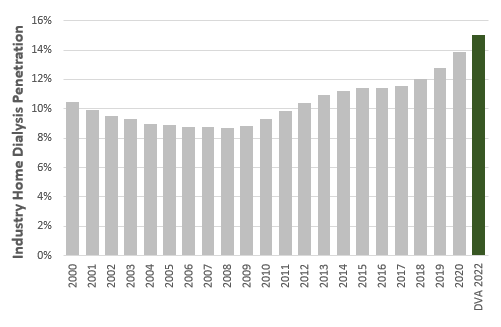

Exhibit P shows home dialysis penetration in the United States using NIH data available through 2020, alongside DVA’s 2022 home dialysis patient penetration. I think it’s safe to say that industry penetration of home dialysis is around 15% today. That penetration has almost doubled over the last fifteen years but is still much lower than most developed countries. By comparison, the United Kingdom is at 20%, Canada is at 25%, and in the most extreme case we have Hong Kong at ~80%.

One expert noted that:

“With in-center dialysis, you’re basically peeing three times a week. That doesn’t make sense physiologically. And they do it Monday, Wednesday, Friday. But now they have a holiday. So there’s a huge problem. Sunday or Monday if they’re not able to get in that dialysis, now they’ve gone two, three days without it. And a lot of these patients end up in the hospital. Now if you think about home dialysis, you can do it six times a week. That’s way healthier”

Conceptually, it makes sense that home dialysis would lead to better health outcomes (frequency of treatment is higher), and result in lower costs to insurers because of lower labor (nurse) intensity and fewer hospital visits (which are a big part of the cost burden). The consensus view seems to be that this is true on both fronts, but I’ve read a few studies that push back on this. For example, a 2019 Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease study that evaluated past research concluded that it was unclear “if the observed survival advantage with home dialysis reflects a true improvement in survival due to the location itself, or if it instead reflects the fact that home and in-center populations differ in terms of other determinants of survival” – for example, younger people are more likely to undergo home dialysis, and those patient populations tend to be healthier to begin with.

Despite the ambiguity in data, I suspect it’s true that home dialysis is a better option than in-center dialysis for patients that can manage it, and that’s a big reason why home dialysis penetration is increasing in the United States. CMS in particular wants to see more home dialysis and has created programs to incentivize that shift. DVA is specifically targeting around 25% home dialysis penetration by 2025. That might be a bit of a stretch, but I think it’s reasonable to expect that DVA and other providers can improve home dialysis penetration to 25% eventually. Beyond that, it’s unclear. For example, effective home dialysis often relies on a caretaker, and since the average age of dialysis patients is mid-60’s, a reliable caretaker isn’t always present. It’s also geared toward healthier/younger patients given some of the complications present with home dialysis. I’ve seen plenty of expert opinions that suggest 25-30% is probably a reasonable steady-state penetration level, and most were adamant that 50% was unachievable in the United States.

So, what happens if DVA goes from 15% of patients on home dialysis to 25% or 30%? At first blush, you’d think that center utilization would fall, but it turns out that home dialysis requires lots of training (on average around 9 sessions over the course of 2-6 weeks) and centers can be repurposed to partially act as training centers. In fact, DVA has already been converting some in-center dialysis space to training space. Home dialysis patients also receive support and monitoring from registered nurses that typically reside at a DVA outpatient dialysis center – so whether the patient is there or not, there are healthcare professionals on-site to support them. Net-net, DVA can still rationalize some center space, but I think they’ll just end up repurposing centers to incorporate training/support centers.

The other interesting dynamic is that 30-35% of patients (adjusted for mortality) that start dialysis at home actually end up doing in-center dialysis after 24 months. It’s not as clear cut as saying 25% of patients can do home dialysis for their entire dialysis journey – different modalities are appropriate for different stages of the patient care roadmap. Against that backdrop, it would be hard for an exclusively home dialysis competitor to come in and steal patients from DVA who provides a more holistic care solution. Not to mention, in a little more than half of all states, home dialysis providers are required by law to have at least one physical center in that state. That’s just one more barrier for home-dialysis startups to overcome if they want to go toe-to-toe with DVA and Fresenius. To-date, I’ve seen no real indication that exclusively home-dialysis competitors have made any dent in the market – even as we sit at 15% home dialysis penetration.

Finally, on economics, it’s not immediately clear if home dialysis is more, less, or equally profitable as in-center dialysis. We can compute DVA’s implied revenue per treatment from in-center and home dialysis patients, and home dialysis revenue per treatment has historically been 25-30% higher despite what’s likely to be lower opex/treatment. At the same time, it looks like commercial payors have higher home dialysis penetration, and because commercial rates are so much higher than Medicare rates it makes it hard to do a true apples-to-apples comparison. All that said, the CMO at Humana indicated that DVA “can still make the same amount of money” from home dialysis as in-center dialysis – “everyone wins”. I loosely hold the view that home dialysis margins aren’t – and won’t end up being – materially different from in-center dialysis. If operating margins did end up being identical, but DVA could rationalize some of their center footprint, the shift to home dialysis might even lead to better ROIC.

All told, disruption in a business model always introduces some risk, but in this case, I think the large incumbents are well positioned to manage this continued transition. One reason I feel comfortable with this view is that I haven’t seen any compelling evidence to suggest that economics or DVA’s competitive position have deteriorated as home dialysis penetration increased over the last decade.

Risk #4 – ESRD Prevention

The CDC estimates that as many as 9/10 adults with CKD don’t know that they have CKD, and 4/10 adults with severe CKD don’t know they have CKD. This explains why 30% of CKD patients crash into dialysis and 60% in aggregate have unplanned entry into dialysis. As a layman, those are absurdly disappointing numbers. I have to imagine that if more adults with CKD were aware of their condition that fewer people would end up on dialysis because they’d have earlier nephrologist intervention to slow the progression of CKD. I don’t have a view as to whether or not CKD identification will improve in the future, but it’s difficult to see how it could get any worse – the risk is clearly skewed to better CKD identification over any long period of time.

Even when CKD is identified, there are some good arguments to be made that CKD management hasn’t always been great, and some of the blame seems to be allocated to how providers get paid. Historically providers were paid under a fee-for-service model, and this seemed to result in care gaps and a less holistic approach to managing illness. In recent years, new value-based care models of payment have been rolled out that should help with better CKD management and ESRD prevention/cost reduction. One such model is the CMS Kidney Care Choices Model, where providers basically receive a fixed capitation payment for managing the total care of patients with late-stage CKD or ESRD and share in a portion of the savings they generate relative to benchmark rates. This model in-part creates financial incentives for providers to delay the onset of dialysis through better holistic CKD management. So, the transition from fee-for-service to value-based care could very well lead to a lower prevalence of ESRD. It could also lead to more transplants, because transplants are a cheaper treatment option than dialysis and the “savings pool” available to providers would be quite large. Value-based care isn’t a new thing, but it’s certainly become much more popular for the CKD/ESRD population over the last 5 years. It’s probably too early to judge if this has had any impact at slowing growth in the ESRD population, but intuitively I’d expect this to be a modest headwind for DVA treatment volumes over time.

I talked earlier about some of the risk factors for ESRD – primarily diabetes, which itself is a function of obesity. Another risk to DVA is that obesity/diabetes prevalence falls, which in turn reduces ESRD prevalence. I didn’t initially think this was very likely, but then I came across an interesting argument for why it could happen. This is way beyond my circle of competence, but there are two types of drugs used to treat type 2 diabetes: GLP-1 drugs, and SGLT2 inhibitors. They are intended to lower blood sugar levels and contribute to weight loss (among other nuances) which has all sorts of ancillary benefits. Apparently, both classes of drug can “reduce the risk of cardiovascular and renal adverse events”.

The first GLP-1 drug received FDA approval in 2005, and the first SLGT2 inhibitor received FDA approval in 2013. In the grand scheme of things, both are relatively new drug classes (adoption takes time, and the benefits of adoption take even more time to realize). It doesn’t look like those early iterations had any real impact on the CKD population to-date, but there are new iterations coming out all the time. For example, Novo Nordisk recently developed a new iteration of the GLP-1 drug called Wegovy, which received FDA approval in 2021. Wegovy was specifically approved for weight management, and Novo Nordisk claims that it can help overweight people “shed 35 pounds or more, reducing a major risk factor for kidney disease”. That could have a meaningfully positive impact on obesity rates, which in turn could end up reducing ESRD prevalence over a long period of time. Another example more directly tied to kidney disease today is Farxiga, which is an SGLT2 inhibitor produced by AstraZeneca that got approved by the FDA for kidney disease treatment in 2021. The DAPA-CKD clinical trial for Farxiga “reduced the relative risk of worsening renal function, onset of ESRD, or risk of CV or renal death by 39%... compared to the placebo in patients with CKD Stages 2-3 and elevated urinary albumin excretion” – that is to say, the number of patients that experienced one of those end points was 39% lower than the control group (not necessarily a 39% reduction in ESRD alone). Apparently, it’s only effective for a particular type of kidney disease, but those are impressive numbers. Whether it’s Wegovy, Farxiga, or some other iteration of a GLP-1 or SGLT2 drug, it does feel like there are some advances being made that will slow the progression of CKD and potentially reduce the risk that CKD patients end up with ESRD.

Every time I look at the healthcare space, I’m blown away at how slowly things change. I don’t think improving CKD/ESRD outcomes will be any different. It wouldn’t surprise me if ESRD prevalence didn’t decline for decades. But at some point – whether it’s 5 years or 20 – it feels inevitable that we will come up with better CKD identification techniques, CKD- or root-cause treatments, and better care for a disease that impacts 15% of the population and is incredibly costly to treat if it progresses. Because it’s hard to predict how some of these things will unfold, this is one of the risks that would weigh on me if I were a DVA investor. Fortunately, there is a hedge to this risk, which is DVA’s Integrated Kidney Care (IKC) business, but I’ll get to that further down.

Risk #5 – Transplants

As I discussed earlier, the demand for kidney transplants far outstrips supply – if the supply-demand gap ever improved it could significantly reduce demand for dialysis. There are two ways the supply side could change: increase the supply of organ donors (both dead and alive); and/or, someone invents a commercially viable artificial kidney.

To the first point, Exhibit Q shows total U.S. kidney transplants broken out by donor type (living/deceased) alongside the % of the dialysis population that received transplants that year. Even though total transplants/year have nearly tripled since 1990, transplant growth had failed to keep up with ESRD growth until recently, which led to a worsening transplant shortage. One reason is that the number of living donors has declined modestly since the early-2000’s. The National Kidney Foundation suggests that one reason living donors have declined is that financial barriers like lost wages, childcare, and elder care haven’t historically been reimbursed to kidney donors. In 2019, the President issued an Executive Order on Advancing American Kidney Health aimed at reducing those financial barriers. Initially, that order didn’t do much, but in October 2020 the US Department of Health and Human Services started allowing for living donors to be reimbursed for all these items. The National Kidney Foundation estimates that by doing so the annual supply of living donors could increase by nearly 15,000 from just ~6,000 today! In the 2.5 years since those rules changed, we haven’t seen any real growth in living donors, although COVID disruptions probably acted as a headwind on that front. I’d monitor this theme closely over the next few years (OPTN releases monthly data), because if the National Kidney Foundation turns out to be right, that would take a decent bite out of dialysis demand.

The other challenge with organ donation is the supply from deceased donors. The medical criteria for considering a deceased organ used to be sufficiently narrow that a lot of viable organs were being discarded. According to the OPTN, the “medical criteria for deceased organ donation continue to broaden based on favorable clinical experience, and increasing proportions of donors coming from less traditional categories of eligibility”, which has contributed to rapid growth in deceased kidney organ supply. Since 2014, that looks to be the primary driver for improving transplant rates (as a % of the dialysis population) and seems set to continue. A study completed as recently as 2019 (link), using 2015/2016 data, showed that the U.S. was still discarding a significant portion of kidneys from deceased donors based on the results of biopsies. Of the discarded kidneys, the study found that 45% could have made for viable transplants and would have been used in transplants in France and Belgium where preimplantation biopsy findings “are generally not used for decision making in the allocation process”. Those discarded kidneys would still lead to better mortality rates and quality of life than if patients instead remained on dialysis. I don’t have a strong view as to how the supply of deceased kidney organs will trend in the future, but there does appear to be some low-hanging fruit that could improve organ availability and a strong desire to pluck it. There are also relatively simple changes to the donor system, like moving from an opt-in to an opt-out model, although I haven’t seen any explicit movement to do that in the United States.

In addition to human kidney donors, there is some experimentation going on with xenotransplantation. For example, there have been a few attempts/experiments using pig kidneys in humans. Historically most of these experiments had been unsuccessful, but in 2021 surgeons at NYU Langone Health used a genetically engineered pig kidney in a transplant surgery with a brain-dead human and saw no signs of immediate rejection during the 3-day study. In my view, xenotransplantation feels a lot more like a science experiment than a true long-term solution to bridging the transplant gap. Even if the medicine advanced enough to make xenotransplants effective (that could be decades away, if ever), there are plenty of ethical concerns and commercial constraints. So, I don’t think this is a real risk to DVA, but I bring it up to highlight how much medical effort is going into finding transplant solutions.

Finally, there is always the risk of artificial kidneys. There are a few projects that are underway right now and look promising. For example, KidneyX is a public-private partnership between the US Department of Health and Human Services and the American Society of Nephrology, and they hold competitions to accelerate kidney innovation. A big part of what KidneyX is trying to accelerate is the development of artificial kidneys, and in 2021 they provided funding to 6 projects that won the Artificial Kidney Prize, Phase 1. One of those winners was The Kidney Project, which is a collaboration between multiple universities and is working on a device called iBAK. They have a prototype iBAK device today but estimate that they are 4-5 years away from human clinical trials if they can get the resources to keep progressing. If all goes well, they estimate that a commercial device could be available by 2030. This is all speculative – they need funding, they need to prove that the device works and is safe, and they need to make a commercially viable product ($ is a factor). Even if 2030 proves to be an optimistic timeline, projects like this appear to be making progress and I think it’s inevitable that an artificial kidney eventually comes to market. When that happens, it could quickly kneecap demand for dialysis.

Whether it’s improving supply of human kidney donations or the development of an artificial kidney, any advances here could seriously impair dialysis businesses. Again, this is a difficult to predict risk. It’s far enough in the future that DVA’s business is unlikely to be materially impacted in the next 5 years, but as soon as any meaningful milestone gets crossed (say iBAK moves into human trials) that risk could get priced into implied expectations. This is another thing that would keep me up at night.

Despite the risk, it’s worth noting that less than 20% of dialysis patients are on the transplant list right now. Part of the reason is that transplants are risky endeavors. The average age of dialysis patients is 65, and many dialysis patients have comorbidities that increase the risk of transplant surgery. As a result, many of these patients wouldn’t survive a transplant surgery (or would be prone to post-transplant complications), particularly those in their 70’s or 80’s. Even if an artificial kidney could address some of these concerns, like the risk of organ rejection, it’s worth remembering that 30% of ESRD patients crash into dialysis and 60% in aggregate have unplanned entry into dialysis. So, unless CKD identification and ESRD prediction improves alongside transplant availability, there would still be some dialysis demand to bridge the gap between unplanned dialysis and a transplant surgery.

Risk #6 – Thoughtless Regulatory or Legislative Action

For obvious reasons, dialysis receives a ton of criticism from all angles. When that scrutiny leads to thoughtful changes in the delivery of dialysis, I think that’s a good thing for patients, and often a good thing for DVA. But when that criticism leads to thoughtless proposals, it’s a danger to everyone in the ecosystem: patients, healthcare workers, and DVA. Nowhere is this more evident than California.

For example, in 2018 the Service Employees International Union – United Healthcare Workers West (SEIU-UHW) introduced Proposition 8, the “Fair Pricing for Dialysis Act” which was added to the California statewide ballot. Proposition 8 would “cap dialysis providers’ profit at 15 percent above what they spend on direct patient care services costs”. Recall that DVA already loses money on every patient covered by a government program and has to generate obscene margins on patients covered by commercial plans just to break even. If Proposition 8 passed, it most likely would have resulted in the majority of California dialysis clinics getting shuttered. And that’s not just biased messaging from DVA and Fresenius. Satellite Healthcare, the largest non-profit dialysis provider in California, stated that if Proposition 8 passed Satellite Healthcare would lose $40/year and would be forced to immediately shutter clinics. DVA, Fresenius, and U.S. Renal Care collectively spent ~$110mn to defeat the ballot initiative.

And then in 2019 California’s governor signed AB 290 into law, which capped dialysis reimbursement at the Medicare rate for any commercial patients receiving third-party financial assistance from entities like the American Kidney Foundation (AKF). AKF immediately announced that they would be withdrawing from the state of California, and then filed a suit asserting constitutional challenges to the bill. DVA, Fresenius, and U.S. Renal Care followed up with their own suit. A month after those suits were filed, a federal court granted a preliminary injunction to prevent AB 290 from going into effect. This issue hasn’t been settled, and it’s not clear how it will play out, but the court did say “considering both the likelihood that A.B. 290 will abridge plaintiffs’ constitutional rights and the extreme medical risks it poses to thousands of ESRD patients, the court finds it obvious that the public interest favors a preliminary injunction, and that the balance of the hardships tilts strongly in plaintiff’s favor”. I think it’s reasonably likely that AB 290 never goes into law, but if it did, DVA could see significant margin compression in California. If other states followed California’s lead, it would meaningfully impair profitability. Steps like this would most likely put a lot of small dialysis centers out of business, and potentially open the door for DVA and Fresenius to take even more share, which could counter some of the margin compression. But again, I think this is unlikely, because ultimately nobody wants to see DVA and Fresenius with more market share.

Those were just two examples, but SEIU-UHW has also introduced multiple additional proposals since 2018 that DVA has had to fight. It almost looks like this union is trying to exert pressure to on DVA and Fresenius to allow for unionized labor and patients are getting caught in the cross hairs. Whatever the reason, DVA has spent hundreds of millions of dollars over the last five years to combat these proposals and bills like AB 290. So not only does this introduce some tail risk, but it’s also very costly to defend against. I expect that this will be a perpetual cost of doing business for DVA.

Ancillary Services

While the U.S. Dialysis business is responsible for all DVA’s operating income today, there are two other businesses that show some promise: international dialysis and DaVita Integrated Kidney Care (IKC). Technically there are a few other small things in Ancillary Services, but those are the two that stand out in this segment. Combined, these businesses have never generated an operating profit (Exhibit R), but I think there is a clear path to profitability within 3-4 years.

International

At the end of 2022 DVA had 350 international dialysis centers across 11 countries, although 60% of these centers were concentrated in just three countries: Brazil, Poland, and Germany. Exhibit S shows total international centers from 2011-2022 alongside unit revenue, opex, and operating income (I had to estimate 2011-2013 opex and operating income, but DVA did report revenue).

Opex per center has been stable over time, so the likely reason DVA had historically generated an operating loss from the international business is that center utilization starts low and ramps up over time – hence revenue/center increasing significantly over the last decade. It might also be that DVA hasn’t yet recognized many of the scale benefits they enjoy in the United States. In 2020 this business flipped from being a drag on operating income to being a contributor, but operating margins last year were still a measly 5.3% ($37mn). That is significantly lower than average operating margins from the U.S. Dialysis business of 18-19%. I haven’t bothered going down the rabbit holes of how dialysis works in Poland or Brazil, so it’s not immediately clear if dialysis is just less profitable outside of the U.S. or if DVA should continue to see margin expansion over the next few years.

What I did do is look at Fresenius financials, because they have a sizeable dialysis business outside of the United States. For Fresenius, operating margins from international dialysis operations were nearly identical to their U.S. operating margins. That might be because Fresenius’ international business is >8x larger than DVA’s, and they’ve already achieved the benefits of scale. It’s possible that DVA continues to scale their international business and simultaneously delivers top line growth and margin expansion. For illustrative purposes, if they doubled their international center footprint and achieved 12% operating margins once those centers mature, they’d generate ~$170mn in operating income (~4x more than 2021/22). While I would consider that a substantial “win”, it would only increase total operating income by something in the range of 10%. I wouldn’t pay a lot for this upside, but it’s certainly a nice option.

DaVita Integrated Kidney Care (IKC)

IKC is another business with interesting potential, but one where I think the path to operating income growth is more clear. Integrated care providers effectively take a patient under their umbrella and are responsible for coordinating all their health needs – in DVA’s case, they specifically serve CKD and ESRD patients. The IKC care team works with patients to coordinate physician appointments, consult on treatment options and insurance coverage, track immunizations and medication usage, and craft kidney-friendly diets. They will monitor labs and health data from all physicians that a patient sees (which helps with managing comorbidities) and recommend changes to treatments if necessary. The care team is also available 24/7 to answer questions and provide support.

Roughly 80% of DVA’s IKC patients are under a risk-based care model, where DVA shares in part of the savings from managing those patients relative to benchmark spending levels. Savings largely come about by taking preventative action, which helps patients avoid costly hospital visits, manage the transition from CKD to ESRD more smoothly, encourage more home dialysis, and potentially improve transplant rates. I don’t have exact numbers, but it looks like DVA’s IKC patient split is roughly 50/50 late-stage-CKD/ESRD.

While DVA has technically had some form of integrated care model for 5-10 years, it really started to take off in 2021. An Executive Order in 2019 directed CMS to create new payment models, and the first such model launched in 2021 called ESRD Treatment Choice (ETC). ETC was a mandatory model that went live in 30% of dialysis centers across the country. A new voluntary model called Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting (CKCC) launched in January 2022, which DVA is also participating in. The CKCC model in particular is a risk-based/value-based model, and a large share of DVA’s IKC patients would be covered under one of the CKCC options.

DVA started reporting total IKC patients under their care in 2021, and in 3Q21 they had 22,000 patients with about 73% under risk-based care arrangements. As of 1Q23 they covered 82,000 patients with 82% under risk-based care. That’s nearly a 4x increase inside of 2 years. To put this in perspective, DVA treats ~200,000 ESRD patients in their U.S. Dialysis business. If we assume that 50% of IKC’s patients have ESRD (vs CKD), then they’d be at 20% penetration. At the 2021 Investor Day they showed a long-term target of 200-300k IKD patients, where 100-150k would have ESRD. That would likely work out to 45-60% penetration if their ESRD population continues to grow.

The economics of this model are a little weird. To start, Exhibit T shows ESRD patient economics, with total benchmark spend, targeted savings, and the savings split. But these are steady-state economics, and timing matters a lot.

Exhibit U shows illustrative economics based on how many years the patient is under IKC. In Year 1, DVA doesn’t recognize any revenue because savings haven’t been confirmed. Savings start to get realized in Year 2, and are expected to increase for a few years before reaching a steady-state by Year 5 – that’s where DVA expects to generate $2-4k/year in net savings.

The $2-4k of net savings are after variable costs (“model of care costs”) but not fixed costs, which seem to be $100-125mn/year. At the mid-point of both metrics, you’d need 37.5k mature IKC patients to break even – and no new patients (which would generate an operating loss in Year 1). Keep in mind all of this applies to ESRD patients – earlier stage CKD patient economics are much worse because benchmark spend levels are so much lower and that obviously leads to lower available savings.

In 2022, DVA likely had 25-30k ESRD patients in IKC (just short of the breakeven threshold), but 52% of those patients were in Year 1 – it’s therefore no surprise that IKC generated a $125mn operating loss. As of 1Q23, it’s safe to say that IKC has surpassed the benchmark 37.5k ESRD patients to breakeven (likely at ~40k), but 42% of these patients are in Year 1 and 30% are in Year 2, which means we should expect that DVA will still generate negative operating income for 2023. So long as IKC continues to realize high-double-digit patient growth, it’s reasonable to expect that they’ll keep putting up operating losses. But as patient growth plateaus, this business could go from a $125mn operating loss to something just shy of $200mn in operating income – a $300mn swing! That would be nearly a 20% increase in DVA’s total T5Y average operating income. Quite the tailwind. DVA’s management team initially guided to IKC breakeven by 2025 but is now guiding to 2026. I built my own IKC model (which you can find in the Excel file at the top of this post), and I think 2026 is a reasonable estimate if IKC patient count doubles through 2026 and then plateaus shortly thereafter.

For illustrative purposes, Exhibit V shows hypothetical IKC patients and expected operating income by year, where I tried to approximate 2021-2023 actuals for years 1-3.

In my view, this is probably the most exciting thing happening at DVA today. It’s also a semi-hedge against lower dialysis demand if that demand-destruction comes on the back of better ESRD prevention or higher human donor transplant rates (which would directly contribute to higher life-time savings/patient).

DVA isn’t the only organization pursuing the integrated care business, so we should expect some competition. That being said, I think they are well positioned to capture a significant share of their total ESRD population, and a large portion of late-stage CKD patients. One reason is that they already have relationships with 45% of all nephrologists in the country and are already treating 37% of all ESRD patients – they’ve got the top of funnel and the patient relationship already secured. By virtue of already serving all these patients and working with all these nephrologists DVA is also sitting on a treasure trove of data, which should help them achieve better-than-average savings through integrated care.

Another reason that DVA is well positioned to capture integrated care patients from health plans that have a choice of who to contract with, is that they seem to rank quite highly from a treatment quality standpoint. All dialysis centers in the country get rated by the CMS ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP). It’s a 5-star rating model where a 5-star rating is the best and 1-star the worst. The rating is based on a combination of patient feedback, clinical care, safety, and care coordination metrics. Roughly 90% of dialysis centers in the country have a rating, and I pulled all that data from the CMS website. Exhibit W shows the rating distribution for DVA, Fresenius, and the rest of the industry for centers that have a rating. We can see that DVA ranks slightly above Fresenius, but its significantly better than the rest of industry. For example, 65% of DVA’s centers have a 4- or 5-star rating, while only 43% of the rest of industry has a 4- or 5-star rating. If you’re a health plan looking to partner with a risk-based care organization, data like this would suggest that DVA may generate better savings than some other competitor, which in turn would put more money back in your pocket.

Balance Sheet and Capital Allocation

Thanks in large part to the fact that dialysis treatment volumes and reimbursement rates/treatment have historically been relatively predictable/stable, DVA has comfortably utilized significant leverage in their business. Exhibit X shows historical ND/EBITDA and a breakdown of total capital.

Absolute debt has increased substantially and now sits at nearly $9.0bn. If you normalize results from the U.S. Dialysis business, 2022 would be sitting at ~3.5x ND/EBITDA, which is at the high end of their 3.0-3.5x target range but not that different from where they’ve been for most of the last decade. What’s wild to me is that a measly 7% of the total capital in this business today is common equity (2012-2018 looks odd because of an acquisition and subsequent disposition that I haven’t talked about but isn’t relevant to the business today). DVA has managed to grow EBITDA by nearly 7x from 2000-2022 with almost no incremental equity and pretty manageable debt metrics. What a track record.

Since so little equity is used to run this business, return on common equity is a silly high number – the average book value of common equity was just $734mn in 2022 on net income to common shareholders of $547mn, which results in a ROE of 75%. And that’s on 2022 net income that’s likely artificially low. That compares to an ROIC of just 10%. DVA doesn’t have significant reinvestment opportunities anymore, so it’s not like high ROE matters a ton, but it’s still an impressive figure. Part of the reason that book value of common equity is so low is that DVA has repurchased a boat load of stock since 2015. From 2015-2022 they repurchased 58% of their common shares at a weighted average price of ~$73/share.

If you look back over the past two decades, you’d notice two distinct eras with different capital allocation priorities. Pre-2014 DVA reinvested 70% of their NOPAT in both organic and inorganic growth and took their U.S. dialysis market share from 13% to 36%. Post-2014 that reinvestment rate fell to 26% and DVA instead returned significant capital to shareholders via buybacks – U.S. dialysis market share has remained essentially flat since 2014 (note that I adjust reinvestment rates for the purchase/sale of DMG). Exhibit Z shows that both capital allocation eras delivered strong EPS and FCFE/share growth.

Looking forward, I suspect DVA’s reinvestment rate will be even lower than 26%. There just aren’t that many centers left that they could buy, and I don’t expect that there is a long organic runway left. As such, I think they’ll toggle between buybacks and debt repayment. I’ll circle back to this in the valuation section, but so long as dialysis demand continues to grow, I think they can likely reduce ND/EBITDA to 3.0x, repurchase $8-9bn of stock over the next decade, and deliver low-single-digit NOPAT growth. To put that into perspective, the current market cap is $9.4bn.

Management, Governance, and Culture

Kent Thiry was the CEO of DVA from 1999-2019, and he created one of the weirdest corporate cultures I’ve ever come across. Less than 2 years into his tenure as CEO he decided to start referring to DVA as a village instead of a company, the people working there as teammates instead of employees, and himself as the mayor instead of the CEO. The overarching idea was that Kent wanted to create a sense of community and purpose, and using this unique language would raise the bar for expected behavior. It sounds corny, but it honestly seems to work. For an example, watch this video (link) – start at 2:20 and see what happens when Kent asks DVA teammates to stand up at this Stanford event. The entire video is worth a watch because it paints a great picture of why Kent made this cultural change and how he thinks it led to superior results - he talks about how DVA employee turnover is lower than comparable businesses, how they rank very well on quantifiable care measures (like the CMS Star ratings), and how that all leads to superior financial performance. As the mayor he treats DVA profit like tax dollars – “who should pay how much tax, how transparent is the deployment of the tax funds that are raised, how competent are the organizations that spend the tax money… we don’t get to grow and create career opportunities unless we’ve collected taxes and are allocated capital”. As an allocator of tax dollars, I’d say Kent Thiry’s track record was really good – organic spend, M&A, and buybacks all appear to have added value to teammates and shareholders. There was one blemish – the acquisition of their DMG business – but they realized the mistake, sold the business, and seem unlikely to go down that road again.

Despite the corny language that DVA has adopted, I think I’ve bought in to the idea that this does lead to better patient outcomes and financial performance. Maybe the benefits on any single measure are only marginal, but if you can outperform the status quo marginally across all measures, then in aggregate I think that could lead to significant value creation for all stakeholders.

Javier Rodriguez joined DVA in 1998 and took over as CEO in 2019 when Kent Thiry stepped down – tough timing for him because inside of 12 months DVA was grappling with COVID, which can’t have been easy for a healthcare business to navigate. Under Javier’s leadership, DVA has distributed the vast majority of their FCF via buybacks. They’ve completed very few acquisitions, and instead focused on leaning into IKC and optimizing the U.S. Dialysis business as patient and treatment volumes declined. I think those were the right moves. From what I can tell, Javier has bought into the village concept and is unlikely to change culture in any material way. All told, I think you can expect more of the same going forward, and that’s a good thing.