Investment Thesis

Costco (COST 0.00%↑) is the second largest brick and mortar retailer in the U.S., growing sales at an 8% CAGR over the past decade and gaining share in both the U.S. and international markets. The company offers good quality merchandise at prices that virtually none of their competitors can compete with.

Costco’s edge comes from having high volume per SKU and massive scale, which results in pricing power over suppliers and allows them to set prices well below their competition. The company also benefits from a membership model, warehouse design, bulk products, highly efficient supply-chain and inventory management processes, discovery-based shopping and treasure hunt items, private label merchandise, and great culture. In aggregate, these help Costco reduce unit costs, which ultimately supports their pricing advantage over peers. In-my-opinion, it would be extremely difficult for other retailers, brick-and-mortar and e-commerce alike, to replicate Costco’s strategy and cost advantage today.

E-commerce is probably the largest risk; the convenience of shopping online could materially impact in-store foot traffic. However, Costco offers a compelling e-commerce solution for bulk and staple-like products today, benefiting from most of the same cost advantages that give their warehouse model an edge. In addition, Costco’s value proposition is focused on providing great value for their customers, which differs from convenience and selection that most of their major competitors like Amazon and Walmart focus on. I believe that this will continue to differentiate Costco from other retailers, both brick-and-mortar and online competitors, and that their predominantly brick-and-mortar strategy will continue to be successful in the face of growing e-commerce penetration.

The company has an excellent track-record of growing profitably and taking share over the past few decades. Despite this historical success, Costco’s opportunity for growth continues to be quite large across both existing and new markets. I expect that Costco can grow sales in both Canada and the U.S. in the 5-7% range over the next decade, and at mid-to-low single digits thereafter. Most international markets remain significantly underpenetrated and present a massive opportunity for Costco to drive top-line growth much higher than North America. I expect international expansion to ramp up over the next few years and to drive above average growth for at least the next few decades.

I also view management positively. Craig Jelinek continues to make culture a priority and has fully adopted the strategy and retailing philosophy that made Costco so successful under Jim Sinegal. The average age of the executive team is quite high though, and it’s likely that we see most of the management team turnover in the next 5-10 years. However, given how engrained culture is among employees, and Costco’s tendency to promote from within, I don’t see this as a big concern; it’s unlikely that strategy will veer significantly under a new executive team.

Despite clear operational prowess, I do note that Costco has returned a significant portion of cash to shareholders over the past decade (through special dividends and share buybacks) when they likely could have reinvested more in the business at attractive incremental returns. There is an abundance of great organic opportunities available to them - filling in the white space in existing markets and adding new markets – and I don’t think that higher organic investments would have resulted in lower incremental returns. In my view, there is some room for improvement from a “capital allocation” perspective. Nevertheless, the conservative culture in place today gives me confidence that new capital won’t be deployed at unattractive returns.

In summary, Costco is a high quality business with a large growth runway and clear competitive edge. Their focus on great value makes them more resilient to e-commerce disruption than some brick-and-mortar peers, and their own e-commerce solution, while somewhat lacking, delivers on their core value proposition. The company has epitomized operational excellence over the past few decades: they don’t miss on new warehouses; they’ve been consistently better on pricing than peers; they’ve relentlessly cut costs; and have maintained a best-in-class culture. Continued success with Kirkland, international expansion, and e-commerce should also support decades of additional earnings power growth.

Unfortunately, investors seem to already understand and appreciate everything that makes Costco great. I struggle to identify where I might have a materially differentiated view to the upside, and the current share price seems to already reflect a fairly optimistic set of assumptions for both topline growth and margin expansion. Costco is an excellent business to add to the watchlist, but it’s difficult to see a path toward above-average returns at the current price. I’d be more excited sub-$350/share.

I encourage you to reach out with feedback or comments if you disagree with any of my analysis. I can be reached at the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

Introduction

Sol Price - a retailing legend - was the innovator behind the warehouse club business model. He opened his first warehouse under the Price Club brand in 1976. Price Club sold high quality products at low prices, with no advertising, low operating expenses, and high sales productivity. In 1982, Price Club went public with 8 locations and ~$500 mln in sales, and their success story sparked a new wave of retailers. In the following year Walmart opened its first Sam’s Club and Zayre opened its first B.J.’s.

Decades earlier, Jim Sinegal, who became another retailing legend, started his career as a grocery bagger at FedMart, a chain of department stores founded by Sol Price. Between 1955 and 1979 Jim progressed into executive VP roles at FedMart/Price Company. During this time, Sol Price became his close friend and mentor. In 1983, Jim and Jeffrey H. Brotman cofounded their own warehouse club called Costco. The intention was to create a carbon copy of Sol’s Price Club. The company was a massive success, and a decade later Costco merged with Price Club to form PriceCostco. Later rebranded back to Costco, the combined entity in 1993 operated 206 locations with ~$16 bln in revenue. Fast forward to today and Costco has expanded to over 800 locations across multiple countries and generates north of $190 bln in sales (Exhibit A).

Jim has executed on the warehouse club model exceptionally well, and the company has consistently gained market share over the past few decades. It now ranks as the 2nd largest brick-and-mortar retailer in the U.S. and continues to expand internationally. Exhibit B shows Costco’s U.S. market share of total retail and food services sales since the turn of the century.

Costco has also outpaced Walmart’s Sam’s Club and BJ’s Wholesale Club, their two main warehouse club competitors. Exhibit C shows historical net sales and membership fee revenue for the three businesses.

The key to Costco’s success comes from a relentless focus on creating an exceptional customer experience; in particular, providing high quality products at low prices. Lots of other retailers tout the same thing, at least around low prices; think Walmart and their Everyday low prices slogan. What makes Costco so unique is the magnitude and consistency of their discount relative to competitors, and their ability to maintain exceptional quality across all merchandise. They drive costs down at every turn and pass most of those savings on to consumers, allowing their members to share in Costco’s scale economies. They do this better than traditional retailers for a number of reasons, which I’ll explore in more detail below.

Membership model

Pricing power with suppliers

Warehouse model and supply chain management

Kirkland Signature

Company culture

Brand equity

Scale advantage

Membership model

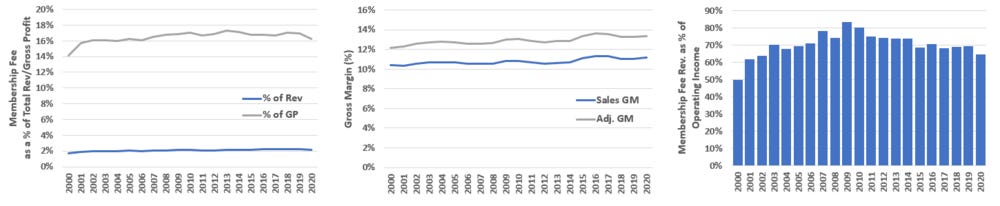

Costco operates under a retail subscription model, similar to Amazon and their Prime membership. In fact, Price Club was probably one of the first retailers to introduce a retail subscription model back in 1976. Members pay an annual fee for the privilege to shop at a warehouse, and in return get better pricing on merchandise. Exhibit D shows that membership fees for Costco account for ~2% of total revenue, ~16.5% of adj. gross profit, and ~70% of total operating income.

At first glance, an argument could be made that membership fees perfectly offset the average annual cost savings per person. Some members subsidize others, but the average person is no better off than skipping the upfront fee and sticking to their conventional retailer.

This doesn’t turn out to be the case at Costco, where savings massively eclipse the cost of membership. Costco doesn’t disclose how competitive they are relative to other retailers, but a collection of sources suggests that their prices are ~15-20% lower than competitors on like-for-like products. For context, if Costco removed their membership fee, the company would only have to raises prices by ~2% for gross profit and operating income to remain unchanged, all else equal.

Another way to think about this is from the member perspective. Exhibit E shows the average revenue per paid membership and the number of outstanding cardholders. The data shows that the average paid member or household unit (excl. household cards) spends ~$2,500 annually. At an average cost savings of say 17%, the typical member generates ~$500/yr in savings, which more than offsets the $60-120 membership fee. This also checks out with what Costco advertises to new members: the membership fee pays for itself within the first trip. At a $60 upfront fee, and an average discount of ~17%, that first basket size would have to be in the $350 range to break-even. If you’ve ever been to Costco, you’d know that this is par for the course. Exhibit E also shows a sensitivity of annual spending and membership fees vs. cost savings. The primary takeaway here is that members are better off so long as the average Costco discount is no worse than ~5%.

It’s clear that the membership model make sense for the customer. Renewal rates have consistently remained in the high-80% range for decades, and even in years when Costco increased their membership fees (2012 and 2017), renewal rates only fell by 1-2% on the year and then subsequently rebounded (Exhibit F).

This model also works well for Costco. One reason is that members have an incentive to spend a disproportionate share of their wallet at a single retailer – the membership fee is a sunk cost that draws the customer in, and if they’re going to stop at Costco for one item, they might as well get everything on the grocery list. Data on Amazon’s Prime membership provides a good anecdotal example of this. In 2014, roughly 40% of Prime members spent over $200 over a 90-day period compared to 13% for non-Prime shoppers. This leads to high volume and inventory turnover, both of which help drive down Costco’s expenses and help reinforce their pricing power.

There are also other less obvious reasons that the membership model can lead to lower prices. One example is the impact on shrinkage. According to Rich Galanti (CFO), Costco’s shrinkage is 0.12% of sales. Walmart and Target don’t report these figures, but the National Retail Federation and a handful of other sources estimate that typical shrinkage in this industry is anywhere from 0.5-1.5% of sales. There are probably a few good reasons why Costco is an outlier (tucking a bulk-sized tub of mayonnaise under your shirt would be… hard), but having your card checked at the door and personal information on file (as a member) acts as a strong deterrent for theft.

All told, higher volume/turnover per shopper and low shrinkage feed into Costco’s ability to offer low prices and helps kickstart the flywheel I discuss below.

Pricing power with suppliers

Part of what separates Costco from competitors is their focus. They’ve invested a considerable amount of time and effort on product research and have built up an excellent track-record of only offering merchandise that consumers want (stuff that sells quickly).

Costco’s average warehouse holds ~3.8-4.0k SKU’s. This compares to the typical Walmart, Target, and BJ’s that average 120K, 100k, and 7.2k SKU’s per location respectively. As well, most of those 3.8k-4.0k SKUs are only offered in bulk. High foot traffic, bulk products, and a low SKU count make revenue per SKU and inventory turnover much higher than traditional competitors. My guess is that average revenue per SKU is 20-40x higher than traditional peers. In fact, some sources suggest that Costco’s top 200 SKUs generate ~40% of the company’s revenue, making volume/SKU for these items much higher. Exhibit G compares my estimates of average annual revenue/SKU in 2020 across a number of Costco competitors. This isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison but still provides a rough sense of the difference between Costco and traditional competitors like Walmart and Target, as well as the other warehouse clubs.

By having fewer SKUs, but much more volume per SKU, Costco ends up with significant pricing power over suppliers; they are often a supplier’s largest buyer. This has resulted in an extremely valuable feedback loop that’s difficult for traditional retailers to compete with and that continues to benefit Costco, their members, and even their suppliers:

The membership model incentivizes members to purchase more = high volume.

High volume gives Costco pricing power with their suppliers, who don’t mind conceding on price to move more product; suppliers can grow their gross profit if higher volume more than offsets the lower prices.

Costco passes most of those cost savings on to consumers.

Those cost savings attract additional members to join the Costco club, increases Costco’s share of their members wallet, or some combination of both, which leads to more volume growth.

Volume growth drives even more pricing power, and the cycle continues.

I borrowed Exhibit H from a great piece put together by minesafetydisclosures.com, which illustrates this concept well.

Costco’s pricing power is likely the single most important driver to their cost advantage over peers, but it’s worth highlighting that high volume/SKU also gives Costco the power to make other demands: pallet configuration, product packaging and quality, and delivery schedules are all strict. For example, suppliers need to secure an appointment with a distribution depot far in advance, and only have a 30-minute delivery window. In aggregate, this helps improve reliability, execution, and transparency, which allows both parties to keep costs, and therefore prices, low.

Costco also manages their risk and exposure to individual suppliers very well. They have a short 13-week commitment window on new products, can approve a new supplier in less than 6 months, and maintain multiple relationships with different suppliers. This allows the company to switch suppliers quickly if they aren’t getting the best bang-for-buck, which helps them maintain their pricing power and reduces switching costs.

This lopsided relationship may seem like suppliers get the short end of the stick, but the volume uplift that suppliers get through Costco has actually made them an extremely important partner, and is why Costco’s pricing power hasn’t eroded over the past few decades. One anecdotal example that I stumbled across was from an unnamed hair product manufacturer. After choosing to start selling through Costco, some high-end hair salons stopped buying from the manufacturer to avoid the impression of selling cheap product. The manufacturer didn’t mind because the gross profit dollar up-lift from Costco was much more meaningful than the gross profit dollar loss from a few high-end hair salons that dropped them as a supplier.

It’s also worth highlighting that bulk products and a low SKU count help Costco in less obvious ways. First, a low SKU count prevents members from selection overload. According to a somewhat dated study (link), fewer choices makes the customer feel more satisfied and confident in their selection, which improves the customers shopping experience and can lead to higher volume through member growth or frequency of visits. Second, as mentioned above, bulk products are much more difficult to steal, which is one of the reasons why Costco’s shrinkage is ~90% lower than traditional competitors. Third, bulk is cheaper on a per unit basis; specifically, packaging and shipping costs tend to be significantly lower, which are cost savings that can once again be passed along to the consumer. And fourth, bulk products result in the customer spending more, or stocking up on items, and is one way that Costco has been able to gain share of retail spending: Don’t worry about picking up mouthwash on your next grocery run, we still have few gallons of that from our last Costco trip. This tweet made laugh:

“You like mayonnaise? Prove it.” - Costco

Despite the low number of SKUs, Costco offers a relatively wide range of products (breadth in categories, but narrow SKU/category). Roughly 75% of the 3.8k-4.0k SKUs in a typical warehouse are basic item; think toilet paper, diapers, and garbage bags. The other ~25% are what Costco calls treasure hunt items. These would be things like a trampoline, Apple Air Pods, limited edition tequila, or seasonal items like winter gloves or barbeques.

A few of the top selling treasure hunt items are on display as you walk into the warehouse, but the rest are spread out around the store. The company also doesn’t label their aisles, which forces the customer to search more of the warehouse and increases the chance of stumbling across these unique items. As well, Costco regularly cycles treasure hunt items: they might hold an item for two months, and then replace it with something unrelated. If you want that product, you should buy it now, because it might not be there when you come back. In-my-opinion, this is an ingenious way to incentivize members to shift from search-based shopping to discovery-based shopping – or at the very least, a search/discovery hybrid. This strategy helps drive an increase in the average basket size, which ultimately leads to better prices for consumers, and market share capture for Costco.

Warehouse model and supply chain management

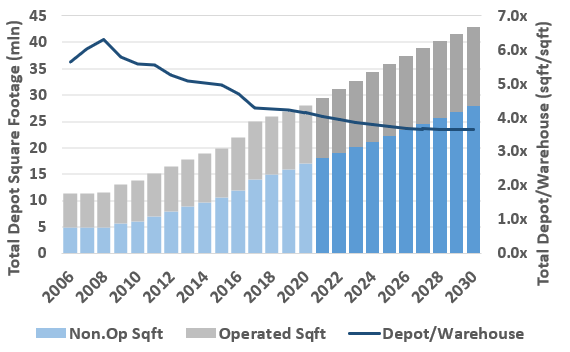

Costco operated 795 warehouses at the end of 2020, and ~24 cross-docking depots. My guess is that the company also relies on about 35-40 non-operated third-party depots/distribution facilities. Exhibit I shows the historical growth and split between warehouses and depots, which includes a few of my estimates to fill in missing data.

The biggest advantage to the warehouse/depot model is that it’s extremely lean. For starters, it lacks many of the supply-chain touch points that traditional retailers are subject too, which reduces labor and handling costs.

A traditional retailer supply chain looks something like this:

Manufacturer ships goods to a third-party distributor, sometimes less-than-a-truckload which leads to multiple touchpoints at both the shipping and receiving ends of the transaction.

The distributor ships to the retailer’s distribution center where inventory is unloaded and either stored or directly shipped out. Again, these shipments can be less-than-a-truckload, which adds touchpoints and costs.

Products are then shipped to the retailer’s store as needed, often in split case quantities for low-volume products or to minimize on-site inventory.

Goods arrive in the backroom and are either stored there as on-site inventory or sent directly to replenish the retailer’s shelf.

With the cross-docking and warehouse model, as well as the low-SKU and bulk-purchase approach, Costco has been able to cut a handful of those touch points out:

Depots receive large truckload or container-based shipments directly from manufacturers. Given the high volume that Costco turns over, these are almost always full shipments. The purpose of the cross-docking depot is to split these bulk shipments and allocate to individual warehouses; they hold very little inventory, and products are generally shipped within twenty-four hours. The depot is responsible for optimizing shipping logistics, which I would guess is relatively easy given the high volume at each warehouse.

Warehouses receive bulk product from the cross-docking depot, typically on pallets, and store the product directly on the warehouse floor in rafters. This results in high density storage, less shipping air, and less time restocking shelves and managing onsite inventory. It’s also worth mentioning that in some cases, products are actually shipped directly from the manufacturer to the warehouse, cutting out a huge chunk of the distribution and logistics network.

Many products are also shipped in ready to display packaging from the manufacturer, and are displayed on shipping pallets in the store. This means that restocking is as easy as plopping a pallet on the floor and removing the shipping wrap, which reduces touch points and labor costs relative to traditional retailers. I like to picture employees ripping around the warehouse afterhours in forklifts, restocking shelves with pallets full of batteries, condiments, and socks. A low-touch, well-oiled machine.

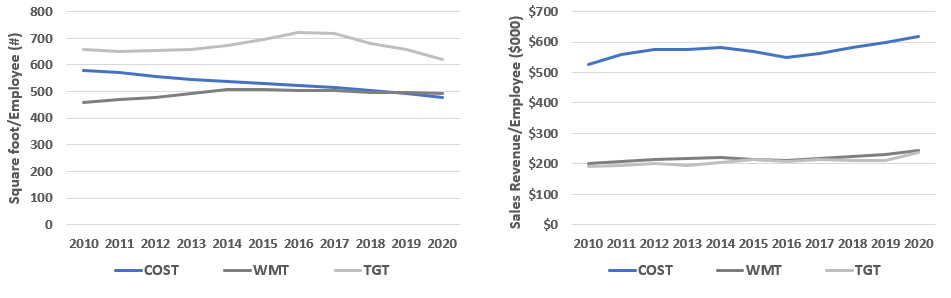

It makes sense that Costco’s supply-chain approach is more cost effective than the typical distribution approach, but alas, it’s difficult to quantify. A few sources, like PWC and APQC, suggest that the supply chain and transportation logistics cost in retail account for anywhere between 10-20% of revenue. A wide range. My guess is that Costco’s supply-chain efficiencies and in-store inventory management give them a ~5-10% cost advantage (as a % of revenue) over traditional competitors. We can also look at sqft/employee and product sales/employee to get a sense of labor utilization and productivity. The values in Exhibit J won’t reflect all of Costco’s supply-chain and inventory management efficiencies and are not a perfect apples-to-apples comparison, but it nonetheless gives us a reasonable indication of Costco’s lead vs. competitors.

The other benefit of the warehouse model is that it’s relatively cheap.

First, as mentioned above, inventory is stored on the sales floor. Traditional retailers don’t do this. A typical Walmart Supercenter will have ~30% of its square footage dedicated to loading bays and back-of-house storage. Exhibit K shows Costco’s sales per square foot and per warehouse relative to other competitors, and Costco is clearly a leader on asset utilization. The company’s high volume and low SKU approach will obviously be the biggest driver here, but I suspect that better utilization of square footage gives them a +20% cost advantage on new builds.

Second, Costco is able to save on aesthetic investments. If you’re saving 15-20% on a few vegetable platters and enough Munchies to feed a high school, you probably don’t really care about the warehouse “look and feel”. Cost savings here are difficult to quantify, but my gut tells me that it’s significant.

And third, Costco warehouses are typically located in industrial areas. The bad news is that you’ll probably have to drive a little further to a warehouse. The good news is that Costco saves on land/land-lease. Again, this is difficult to quantify, but certainly helps at the margin.

I estimate that a new warehouse today costs ~$60 mln on average. Costco doesn’t break down their capital spending between warehouses, depots/distribution facilities, manufacturing facilities, and other, e.g. software and information systems. With some guess work, I’ve tried to isolate for trailing capex/warehouse in Exhibit L. For example, Costco spent ~$450 mln on a chicken plant in Nebraska between 2018/2019 that drove their capital spending higher in these years.

There are two reasons why capex/warehouse has increased over the past few decades. First, the less expensive locations were developed first. As penetration increases in the U.S. and Canada, I expect that capex/warehouse on average will increase. Second, new warehouses are growing in size. The average sqft/warehouse has grown from 143k in 2010 to 146k in 2020, with a handful of new international warehouse additions at >200k sqft.

At ~$60 mln for a 150k sqft warehouse, product sales of about $285 mln, and ~4.5% EBITDA margins, unit economics seem to make sense. On my estimates, and after an initial ramp-up stage, individual warehouses probably yield anywhere from 15-20% ROIC, which checks out with corporate performance metrics.

One drawback to the warehouse approach, like other large retailers, is that these locations are designed to handle a massive amount of foot traffic. It seems to take anywhere from 5-10 years to fully ramp-up. Exhibit M illustrates this and shows warehouse sales by vintage year. This long ramp-up period impacts unit economics, and my guess is that the cash-on-cash yield for a new Costco warehouse is more than 50% lower in year 1 than it is in year 10. The key to generating a high-teens ROIC is longevity of the warehouse – they need to succeed for decades, or the model doesn’t work. Thankfully, Costco savings don’t go out of style. For those that are curious, I provide my warehouse economic assumptions in the model.

An important take-away here is that these new warehouses drag Costco’s average utilization lower. Exhibit N shows average revenue per square foot versus the percentage of warehouses that are less than three years old. There’s obviously a handful of other drivers to revenue/sqft growth at work here, but even after some guess work and adjusting for those, this relationship directionally holds. My guess is that if Costco completely stopped adding new stores today, the ramp up from new stores alone could contribute about ~25-100 bps/yr to topline growth over the next decade. I love this latent revenue growth potential.

Kirkland Signature

Store owned brands (a.k.a. private label) have generally gained share over past few decades. Private label products are generally less expensive given the lack of large marketing campaigns and expensive product packaging. As a result, private label products tend to have better operating margins. Retailers earn lower merchandise margins on branded products, but make-up for it through what’s called slotting fees. This is essentially a fee that the supplier pays the retailer directly to place their product in more strategic parts of the store. The more foot traffic or visibility, the higher the slotting fee, which can be a meaningful contributor to a retailer’s gross profit. However, the slotting fees for less desired shelf space (e.g. shoulder of the isle) can be low enough that gross profits from private label sales can make much more sense than selling branded merchandise. Retailers realized this a while back, along with a handful of other benefits to store owned brands, and, in aggregate, grew their private label share of sales.

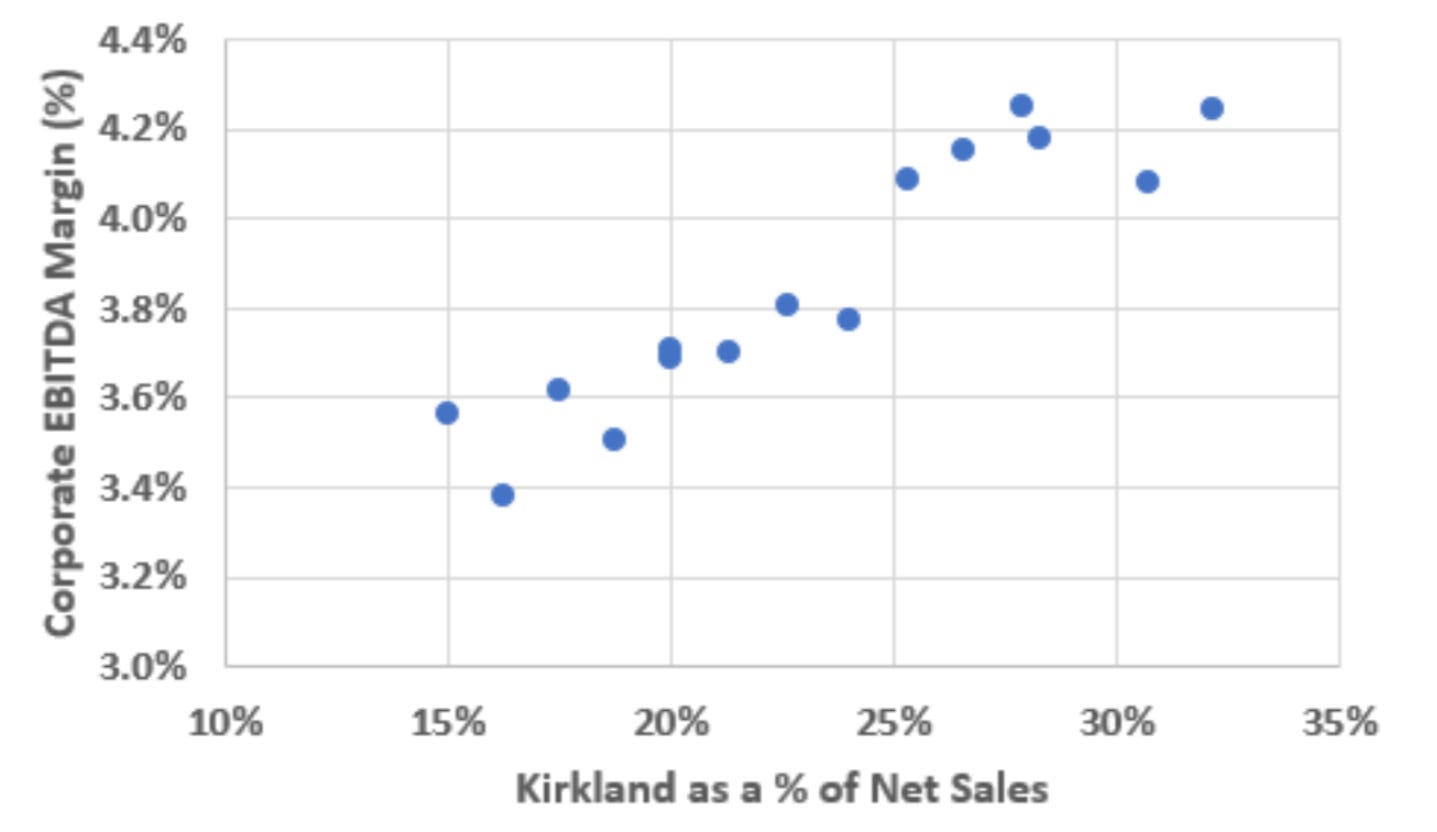

Costco created Kirkland (their own private label brand) in 1995, which now accounts for over 30% of sales. Exhibit O show’s Kirkland as a % of Costco’s total sales. Kirkland has been a massive success and now has arguably similar brand value to the likes of Nestle, Budweiser, and Gillette.

As Kirkland expanded into various product lines, there was essentially two criteria that needed to be met. First, product quality had to be equal or better than similar branded products. In the case of rotisserie chickens, Costco went as far as to invest hundreds of millions of dollars into expanding vertically so that they could have a product that met their standards. In most other cases though, it’s been much easier for Kirkland to meet this hurdle. The scale economies that Kirkland can offer manufacturers is very compelling, even to suppliers that produce competing branded products. From what I can tell, Kirkland products are actually very similar to the branded products that suppliers produce, if not the exact same. Some unsubstantiated rumors are that Kirkland Vodka is actually Grey Goose, or that the Kirkland Golf ball is the same as a Titleist Pro V1. These suppliers might lose some of their branded product share to Kirkland, but 1) if they don’t take on Kirkland as a customer, someone else will, and 2) given Costco’s scale, manufacturing a Kirkland branded product can result in a massive net-volume uplift, helping with revenue growth, but also asset utilization and typical scale economies. So, for the most part, Kirkland quality ends up being at least as good as leading branded alternatives, because it’s the brand owners that tend to produce the Kirkland merchandise.

The second criteria is that Kirkland products need to be cheaper than alternative branded products sold at traditional retailers; somewhere in the 15-20% range. Note that this does not mean Kirkland has to be meaningfully cheaper than other branded products sold through Costco, they just have to be 15-20% less than branded products sold through traditional retailers. In my opinion, many of Costco’s competitive advantages have made this a relatively easy hurdle to overcome, e.g. scale, supply-chain efficiencies, low brand spend, etc.

Similar to Costco’s overall brand equity, the company has spent a considerable amount of effort delivering and building on the Kirkland brand. They’ve consistently produced high quality products at low prices, with very few hiccups. Apparently, Kirkland toilet paper performed OK on absorbency, softness, thickness and dry strength, but most other products that I’ve looked at have great reviews. If you’re a golfer, you should definitely think about giving the Kirkland balls a swing. All of this has resulted in a reliable and trusted brand, which is now one that customers can be confident will give them excellent bang-for-buck.

Kirkland benefits Costco in many ways. First, Kirkland has been able to drive costs down further by saving on massive marketing campaigns typical of most brands, passing some of those savings back to the customer, and keeping some for themselves. Exhibit P shows Costco’s EBITDA margins as a function of Kirkland’s share of total sales. There are obviously a lot of moving parts here, but I suspect that one of the reasons why Costco has grown Kirkland is that it benefits all stakeholders: members and shareholders alike.

Second, private label products are typically less cyclical. Difficult times might not change your vodka intake, but why not save a little with Kirkland Vodka, especially when Google tells us that it’s the same as Grey Goose. It’s difficult to quantify how this impacts revenue variability, but my guess is that it played a role in the past few recessions. See Exhibit Q to get a sense of Costco’s gross profit variability over the past two decades.

And lastly, Kirkland has been such a great success that it’s now offered through other channels, not just through Costco warehouses or Costco.com. Kirkland products are more expensive on Amazon, but the brand actually earns a fair amount of their revenue from selling through third parties. Data from 1010data Market Insights suggests that ~70% of Kirkland revenue in 2016 was tied to sales through Amazon. The quality of this data is low and a bit dated, but it does suggest that Costco has been able to leverage the Kirkland brand to grow their share outside of just the Costco warehouse.

Company culture

“Culture is not the most important thing, it’s the only thing” – Jim Sinegal

Part of the founder’s philosophy, which I believe has been fully adopted by Craig Jelinek, is to get culture right. If everyone is happy and rowing in the same direction, you’re going to be successful.

Costco has consistently ranked as one of the best companies to work for in the United States. They close on holidays. Employees can shop after hours. They provide a lot of career support and promote heavily from within. Employees are constantly busy, which reduces boredom and improves job satisfaction. Employees are paid overtime on Sundays. I’ve even heard some employees talk about how the free-sample stations throughout Costco are basically the employees buffet at break-time. Generally, management seems to be very focused on doing the right thing for employees.

But the best part, and obviously what employees care about the most, is compensation. Costco is ranked as one of the highest paying employers in retail; Exhibit R compares Costco to other large competitors. At first glance, this looks like a bad thing for shareholders, but paying top tier compensation is partially offset by factors like lower employee turnover. I’m not sure what the net effect is, but a dated Harvard Business Review from 2005 (link) would suggest that Costco saves ~$1-2k/employee on turnover per year relative to peers.

Ranking as one of the top employers has other less quantifiable benefits too. For starters, it gives them access to a better talent pool, which can lead to better labor efficiency and customer service. It also, in a small way, helps with word-of-mouth marketing. Employees, and even news outlets, are much more likely to praise Costco about how they treat their employees vs. some competitors. I thought that this was a great example on how this helps the Costco brand come up in everyday conversation (link), but there are loads of other news reports and private discussion that promote the brand.

All told, by having fewer employees per dollar of revenue Costco can afford to offer better compensation per employee, which comes with a host of quantifiable and unquantifiable benefits that likely offset much of the above-average compensation.

Brand equity

The overall customer experience at Costco is unique and, in my opinion, one of the best in brick-and-mortar retail. The value proposition is clear, and they have delivered on their promise to sell high quality products at low prices for multiple decades, which has helped to build a ton of brand equity.

The value of their brand equity isn’t immediately obvious, but a closer look at margins tells an important story. Costco has the lowest adjusted gross margin in the peer group, largely as a function of delivering on low prices. Despite the low gross margins, Costco’s operating margins are in-line with the other warehouse operators, and are only 1-4% below traditional retailers like WMT and TGT (Exhibit S). Put differently, the difference between Costco’s gross margin and operating margins is the lowest in the group. One reason why is that SG&A costs (incl. D&A) are so much lower, driven in large part by the fact that Costco spends way less on marketing than traditional retailers. I’m sure you’ve seen a Walmart commercial, but have you ever seen Costco advertise? They lean almost solely on word-of-mouth marketing. Why say good things about yourself when you can let others do that for you (link, min 5:30). It’s not that Costco has a laissez-faire attitude towards brand, it’s just that they focus on building brand in a much more unique way than competitors.

Here’s the way that I think about it. Rather than actively spending to acquire customers (S&M), they instead make the value proposition and customer experience worth talking about, i.e. low prices/great value. They forgo some cash inflow but save on a different cash outflow. It’s unconventional, but the approach has worked extremely well for Costco. One reason that brands have value is that you learn to trust the product/service. It’s easy to lose trust if you stop delivering on your value proposition, and hard to gain that trust back once lost. Costco has clearly been cognizant of this since day one, and has done a great job at consistently delivering – a few examples are worth highlighting.

Many years ago, competitors in Portland were selling sugar below cost. Costco was worried that if members couldn’t get a deal on sugar at their warehouse, then they might be skeptical of the discount on other products. The company couldn’t rationalize the going rate on sugar, so they actually removed it from their shelves.

The case of the rotisserie chicken is also a great example. The rotisserie chicken became a cheat code for the typical busy shopper. Instead of cooking from scratch after a long day of shopping, you can satisfy a family of four with a hot and ready chicken, all for a small price of $4.99. However, the chickens that Costco sourced from Tyson Foods were growing in size and becoming more expensive for Costco to source. Competitors began to raise their prices, while Costco maintained the $4.99 price point.

“When others were raising their chicken prices from $4.99 to $5.99, we were willing to eat, if you will, $30 to $40 million a year in gross margin by keeping it at $4.99. That’s us. That’s what we do.” - Costco CFO, Richard Galanti.

Customers loved this, which further strengthened the Costco brand. The Costco rotisserie chicken actually has its own Facebook Fan page now (Costco Rotisserie Chicken - Home | Facebook). What’s more impressive is that in order to maintain costs, the company decided to invest in their own vertically integrated, and large-scale chicken production and distribution facilities, competing against the likes of Tysons Foods.

And of course, no write-up on Costco would be complete without at least a small mention of the company’s $1.50 hotdog and soda combo, which hasn’t changed price since 1985.

Costco has historically executed exceptionally well on reliably and consistently delivering on the value proposition, growing the strength of their brand along the way. Going forward, there are probably a few instances where Costco might not be able to deliver high quality at the best price. GoodRX and drug pricing is an example of that. Costco offers generic drugs at a much lower discount than almost every other provider, but GoodRX has found a way to offer even better pricing (see GoodRX write-up for more details). Costco recently acquired a 35% equity stake in a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) to help them manage this business, but I expect GoodRX will continue to be the best on generic drug prices. There are a handful of other one-off examples, but in aggregate, my general view is that Costco will continue to execute well, deliver on their value proposition consistently and across the majority of their products, and continue to grow their brand equity over the next decade+, all of which helps them avoid spending on S&M.

Scale Advantage Expanded

Costco has a massive scale advantage today. Like I mentioned earlier, the company is the second largest brick-and-mortar retailer in the U.S., and sells 20-40x more per SKU than traditional competitors. This is a big driver behind the company’s pricing power, supply-chain efficiencies, high inventory churn and inventory management, brand equity, etc. That said, scale has also benefited Costco in other ways. It allows the company to spend a significant amount of effort and resource on becoming product experts, which helps them maintain quality merchandise and find products that offer the best bang-for-buck. It also helps them monetize their user bases in unique ways, which helps them increase their share of the customers wallet. I provide two examples below that illustrate these points.

Wine

Costco is the largest wine retailer in the U.S., and likely one of the largest in the world. My guess is that wine accounted for ~$2 bln, or ~1.5%, of sales in 2018. By most measures, Costco’s wine and liquor strategy has been a massive success. One reason for this is the quality of wine and liquor that the company offers.

Costco’s scale has allowed them to develop and invest in dedicated product teams. For example, the company has a department of product experts dedicated to kid toys. That team attends toy conferences every year, test new toy’s out, research’s top selling toys and trends/themes in the industry, and then approaches the top toy manufacturers for supply agreements.

Wine is the same. Annette Alvarez-Peters, who unfortunately retired in 2020, was Costco’s lead wine expert for nearly 37 years. According to Wine Spectator, Fortune, and Decanter, she became one of the most influential people in the global wine market. Her and a team of experts were responsible for ~$4.8 bln in wine sales over her tenure, and even though she never obtained her Master of Wine or Master Sommelier certifications, she was nothing short of a wine expert. Not only was her team constantly flown around the world in search of Costco’s next best product, but they also had access to a handful of Masters of Wine and Master Sommeliers to help them with their technical wine education. Without scale, it would be difficult to afford this level of focus and expertise, which has allowed Costco to find and offer great products from around the world.

Vehicle Sales

Costco’s members purchased ~689k new and used vehicles through their Auto program in 2020. This makes the company one of the top three auto retail channels in the United States. Costco’s webpage allows customers to browse for vehicles, and connects them to more than 3k participating dealerships that offer discounted pricing to Costco members.

Instead of earning a take-rate on vehicle sales, Costco collects a monthly fee from dealerships that participate in the program. They don’t even operate the website, which is done by a third-party. The way I see it, Costco has essentially leased out their member network to capitalize on another retail vertical, which wouldn’t be practical or even possible without scale.

E-commerce

Consumer spending habits are shifting online. Why leave your coach when Amazon provides you free same-day delivery on that new yoga mat; Wayfair provides a massive selection of coffee tables to fit your new living room, and of course free shipping; or Instacart cutting out the drive to the grocery store for a small fee? Growth in e-commerce is a strong secular trend that I don’t believe will slow anytime soon. However, I do believe that ecommerce will impact some retailers much more than others.

Large brick-and-mortar retailers that benefit from scale economies will be much less impacted from the shift to ecommerce, specifically Costco. Amazon has gained a massive amount of share over the past few decades because it offers a great combination of selection and convenience at reasonable prices. Despite offering more than ~12mln SKUs, Amazon can keep costs low, and consequently prices, due to scale and very comprehensive shipping and fulfilment network. That said, their high SKU count will make it structurally difficult for the everything store to compete with Costco on price. Costco continues to gain retail share (despite ecommerce share gains) because they have focused less on convenience and selection, and more on value:

“If somebody wants something in an hour, they’re probably not going to get it form us.” – Richard Galanti.

Sure, you can get a family sized pack of toilet paper and olive oil through Amazon, but you add on a flat of soda, enough Ziploc bags for the year, a tub of vitamins, etc., and now you’re looking at a +$400 basket. Amazon might be able to deliver that to your door the same day, but Costco’s warehouse can offer you 15% off. On large basket sizes, this matters.

Don’t get me wrong, a large chunk of the merchandise that Costco sells lends itself well to online sales, specifically Food and sundries that accounted for ~42% of revenue in 2020. However, in-store sales continue to benefit both the member and Costco. In-store shopping lends itself better to upselling and treasure hunt items. There’s a reason why electronics are placed at the entrance, and the rotisserie chicken is at the back of the warehouse. This helps increase Costco’s volume and therefore their pricing power with suppliers. It also implicitly makes the customer bear the cost of collecting the items within the warehouse and last mile delivery, which again are savings that are essentially passed back to the member. Buying items directly from manufacturer, shipping them to a warehouse, and having the customer pick it up continues to be the lowest cost way to service customers.

Despite their continued focus on brick-and-mortar, Costco has done an okay job at building out a competitive ecommerce solution. Surprisingly, Costco was an early adopter of ecommerce. They developed their online capabilities in 1999 and, according to Jim Sinegal, have been profitable since day one. Sales were also fairly resilient through COVID thanks to their ecommerce platform. Costco saw ~80% growth in e-commerce sales in the back half of fiscal 2020, which now accounts for ~7.5-8.0% of Costco’s total sales. See Exhibit T for growth in e-commerce share of revenue over the past few decades. It's worth noting that e-commerce sales include Kirkland products sold on other platforms like Amazon.

E-commerce is still a small part of Costco’s revenue, but growing in importance. It’s also a bit of a different beast than their warehouse business. For starters, Costco has ~8k SKUs online vs. ~3.8-4.0k in-store. All warehouses have 3.8-4.0k SKU’s, but not all warehouses have the same SKU’s, which is mostly why Costco.com offers a wider selection. It also offers additional large-ticket items: patio furniture year-round, an expanded appliance, mattress, and home fitness equipment assortment, and limited time offerings from retailers that need to clean inventory.

The company relies on a mix of their existing infrastructure (depots, distribution centers, and warehouses), and now first and third-party shipping and fulfillment solutions. They’ve partnered with Instacart to help them deliver groceries, and now offer free same-day delivery for larger basket sizes. As an aside, they’re also experimenting with curbside pick-up in three New Mexico locations. Despite other retailers like Walmart successfully rolling this out over the past 18 months, I’m not confident that this will catch on for Costco. If a customer is going to do a trip to a warehouse, it’s compelling enough for them to go inside for an hour to fully leverage better prices.

Costco also recently added to their first-party logistics network by acquiring Innovel in 2020. Innovel provides final-mile delivery, installation, and white glove services for big and bulky products. They own 11 distribution facilities, 100 last-mile cross docking centers, and cover ~90% of the U.S. and Puerto Rico. Roughly 70% of big and bulky orders are now fulfilled in-house. As a result, Costco is taking direct delivery of many items that were previously drop-shipped, which reduces costs and delivery time. M&A hasn’t historically been a part of Costco’s DNA, but I believe that this purchase was a great strategic fit. It makes a lot of sense for the company to lean on big and bulky products. Customers prefer cost savings much more than convenience on larger ticket items like washing machines and refrigerators, and are typically more patient with big and bulky products.

It’s worth noting that you don’t need to be a member to shop online, although bigger ticket items often require member log-in. Products online are typically more expensive than in-store, resulting in the customer bearing some of the cost for convenience. That said, given their cost advantage and pricing power, Costco is still able to offer relatively low prices through their e-commerce platform and, in-my-opinion, it’s a compelling online option for bulk buying relative to competitors. This should help the company maintain their low membership turnover, but also allow them capture further market share by attracting non-members through the e-commerce channel.

Costco will continue to focus on brick-and-mortar expansion over the next decade+, but ecommerce has gained a lot more attention through COVID. My expectation is that the company will continue to invest in their ecommerce capabilities and services, and ecommerce as a percentage of sales will continue to grow over the next few decades. Some of this will be through the Kirkland brand sales through other ecommerce platforms, and some of this will come from direct sales through Costco.com. As well, some of this will be through members spending more online, and some of this will be from growth in non-members using the service. Given their competitive pricing, I expect Costco can gain, or at least maintain their ecommerce share as spending shifts online. I also believe that their brick-and-mortar strategy will be fairly resilient to e-commerce, and expect that Costco can continue to be successful as a predominantly brick-and-mortar retailer for a very long time.

Costco’s Opportunity

Costco has consistently opened 15-25 warehouses per year. The company has also generated a fair amount of free cash flow, and returned ~30% of is back to shareholders through regular and special dividends over the last decade (as a % of operating cash flow). It makes you think that if Costco really wanted to, they could ramp their growth up by 20-30%. Exhibit U show’s warehouses opened per year and sources/uses of cash flow over the past decade.

Costco has had some amazing success in countries like China and Iceland. The first warehouse in China was such a hit that it created a massive traffic jam and authorities had to force the store to close its doors for the day. Chris Bloomstran explains Costco’s success in Iceland very well in Patrick O’Shaughnessy’s Join Colossus podcast (link). Local retailers in Iceland were much less competitive, and Costco was able to offer significantly better pricing. Lack of strong local competition also explains their success in places like Alaska and Hawaii. But there have been other locations that were less successful. In Costco’s earlier days, they entered the U.S. mid-west with two warehouses, closing both down the following year. Despite a few mistakes, performance on both a corporate and warehouse vintage level suggests that management rarely misses on a new builds.

Given their historical hit-rate and remaining white space, I believe that Costco still has decades of room for growth, both in North America and internationally, and both on warehouse penetration per capita and share of customer wallet. I expect that Costco could accelerate annual warehouse openings to ~25-30 warehouses/year for the next +decade, while continuing to return some of that excess cashflow back to shareholders through regular and special dividends, and share repurchases.

U.S.

Starting with the U.S., Costco provides a list showing the number of warehouses per state, which we can convert to a per capita value (see Exhibit V). States like Alaska, Hawaii, Montana, and Washington have about 4-5 warehouse per million people, and seem to be outliers for a handful of reasons that are mostly geographic specific. My guess is that most states can eventually reach about 2.0-2.5 warehouses per million people. Costco will be more/less successful across different states and regions, but, in-my-opinion, the value proposition and competitive moat are strong enough that it’s almost inevitable that the right tail in Exhibit V continues to increase. This means that Costco, in terms of warehouses, is probably approaching fairly stable penetration rates in states like California, Nevada, Oregon, and Utah, leaving ~35 states that should continue to see warehouse penetration increase. Ignoring population growth, if the right tail in Exhibit V was to increase to the 2.0-2.5 range, it would imply an additional 210-330 warehouses on top of the 560 that were operational at the end of 2020. Costco has averaged about 12-14 new warehouses per year in the U.S. over the past decade. If we assume that this trend continues, it implies at least a few decades of growth through new openings in the U.S. Exhibit V includes my forecasts over the next decade, but it’s easy to see how Costco can continue to expand beyond 2030. I expect Costco to open ~15 warehouse/year in the U.S. over the next decade+, which compares to the trailing 10- and 20-year averages of 13 and 16, respectively.

Sales per square foot in the U.S. have also increased by ~4.2% over the past decade, see Exhibit W. One reason for this is that as the percentage of new stores falls, the drag from lower utilized warehouses falls. There are a handful of other drivers here, including inflation, but even after adjusting for some of these it’s still clear that Costco has been able to increase both members per warehouse (Exhibit F above) and their share of customer wallet.

Canada

Costco has been relatively successful in Canada over the past few decades. See Exhibit V for warehouse penetration per capita and Exhibit W for sales per sqft. The company has opened 0-6 warehouses/year in Canada over the past decade, averaging ~2 per year. Penetration in Canada is much higher than in the U.S., but I expect Costco can continue to increase their footprint here, albeit only modestly.

On the other hand, sales per sqft in Canadian dollars has grown at a much faster pace than what we’ve seen in the U.S. One of the reasons for this is that population density in Canada is lower which has led to lower competition in Canada. My guess is that supply chain costs for typical retailers are higher in low population density areas, which allows Costco to benefit more from their low-cost operating model. Lower population density also implies that average travel time to a grocer/retailer might be higher in Canada vs. the U.S. This would mean that travelling the extra mile to a warehouse, which are typically located in lower cost industrial areas, is less of a hurdle than where population density is higher. There may be other drivers that I’m missing here, but whatever the reasons are, it’s a difficult trend to ignore.

International

Costco has operated warehouses in Mexico, U.K., Japan, Korea, and Taiwan for over two decades now. They’ve averaged ~4 new warehouse per year in these geographies. However, Costco expanded into Australia in 2009, followed by Spain, Iceland, France, and most recently into China in 2019. See Exhibit X for Costco’s international warehouse growth.

It makes sense for Costco to expand its warehouse footprint where they already have a meaningful presence. A higher concentration of warehouses should come with scale economies and make Costco that much more competitive relative to local retailers. The warehouse concept is also proven to work well in these geographies and reduces the risk of membership sign-ups. Given Iceland’s population of 370k, or ~2.7 warehouses/mln people, this country is probably fully saturated with the single store. However, I expect that Costco has a fairly large growth runway in most of the other countries that they currently have operations in; see Exhibit Y for warehouses per million people. Australia has seen the most growth in the recent years, which I expect to continue; France is planned to see an additional 15 warehouses over the next decade; and China is potentially a huge market, with expectations to open an additional two stores over the next 18 months.

Costco’s is the leading warehouse club in North America, but also in most of the new geographies that they’ve entered. In fact, this type of warehouse model doesn’t exist in most other places in the world, i.e. the low-SKU, bulk product, low price, and membership warehouse model. In my opinion, it makes a lot of sense for Costco to continue expanding into other geographies. They’ve successfully expanded into four other countries since 2013, with membership signups in the first 8 to 12 weeks of new store openings typically multiples higher than new stores in the U.S. For example, the warehouse in China saw 200k members sign-up within the first two months, growing to ~400k today. This compares to the average U.S. warehouse of ~68k members. International margins have also been better than the U.S., implying that Costco’s cost advantage in new geographies is better and/or that competition is worse (see Exhibit Z).

I recognize that international warehouse growth has started to slow in recent years. There are risks to expanding internationally. Even though the value proposition is extremely strong, cultural preferences might work against Costco. Walmart’s expansion into Germany seemed to have failed for a handful of reasons, but one of those was cultural; Germans were not accustomed to being greeted as they entered the store. Other risks or hurdles that Costco faces include regulation, FX, supply chain reliability, merchandise selection, etc. In my opinion, Costco has a proven track-record of being extremely thoughtful and consequently very successful on where they open that next warehouse, and has proven that their business model travels well. I don’t have a strong opinion on what other geographies Costco may be successful in, but given their competitive moat, the value proposition, and growth in brand value, I expect that Costco will have operations in more than twice as many countries over the next decade or two. All told, I expect Costco’s international warehouse growth to eventually ramp back up to where they were in 2013-2015 era and open 10-15 warehouses per year in both current and new geographies.

Management and Governance

Jim Sinegal retired as CEO in 2012, and from the board in 2018. Craig Jelinek, who has been with Costco since 1984, and was COO between 2010-2012, took-over the reins as President and CEO. These were big shoes to fill, but my general view is that Craig has lived up to expectations.

A big part of Craig’s success was the mentorship he received from Jim. In multiple interviews and lectures, Jim emphasizes the invaluable experience and insights that he learned from his mentor. He acknowledges that Sol Price was an instrumental part of his success and has seemed to be adamant on paying that forward to Craig. And it shows. Craig has proven to be as thoughtful about Costco’s operations and strategy as Jim was, and has maintained focus on executing to Costco’s core values. The company continues to maintain the price of the hot dog and soda combo: “Trust me, that [price] is never going to change. If I have to subsidize it personally, it’s not going to change.” They’ve increased employee compensation to continue ranking as one of the best paid retailers. And, most importantly, they remain unwavering to their dedication in sharing as much of their scale economies as they can afford with their members. “Everything that we do at Costco is not to figure out how much we can make; it’s [about] how little we can make and still pay our bills because we want to sell more.” On most performance metrics, you wouldn’t be able to tell that the keys to Costco changed hands in 2012.

The rest of Costco’s management team appears strong and deserves equal credit for the company’s success. Average tenure of the executive team is >20 years, which is evidence that Costco focuses on developing their people and prioritizes promoting from within. Nevertheless, it can be good for businesses that have been around for as long as Costco to bring in outside talent: a fresh set of eyes to tackle old problems in new ways. For example, I’m not sure if the current team is the best suited at integrating technology into their business, both hardware and software. For example, the company finally brought back self-checkout kiosks in 2019 after a less successful attempt at this back in ~2013. That said, I believe that Costco’s current strategy is relatively simple and will continue to yield great results, and that current team members are some of the best to execute on this.

One potential blemish on managements track record is the ~$13 bln of cash returned to shareholders through special dividends over the past decade, which I view as a kind of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it’s great to see management return cash to shareholders rather than pursue low ROIC projects. On the other hand, given Costco’s opportunity set, how valuable their brand is, and typical warehouse ROICs of ~15-20%, I’m inclined to believe that Costco could have earned at least low-to-mid teens ROIC if that cash had been redeployed in the business rather than returned to shareholders. By 2015, Costco returned ~$5 bln of cash through special dividends. In my opinion, this should have been a signal to management to grow their team and focus more on growth, specifically in international markets. Management would have been rewarded for higher growth too. Executives have ~80% of their compensation tied to RSUs that vest over five-years, and are awarded based on total sales growth and pre-tax income targets. In my opinion, this suggests that either allocating additional capital at mid-teens ROIC is more difficult than I thought, or that Costco hasn’t expanded their team and capabilities to support higher growth. I’m inclined to believe the latter, and think that there’s some room for improvement here.

Another small concern worth highlighting is that the average age of the executive team is ~68 years old. The average age of the board isn’t much different, with Charlie Munger at 96 taking the lead. The company executed well in replacing Jim Sinegal with Craig, but there is some risk of high c-suite turnover in the next few years. Given their focus on developing people within Costco, I don’t think this should be a big concern, but I do expect to see lots of new faces in ~5 years’ time.

Valuation

Costco has taken the idea of shared scale economies to the extreme, and has become a retailer that no one competitor can ultimately beat on quality and price. Most of what drives their cost advantage is supported by a strategy that’s difficult for existing retailers to replicate today – low SKUs, bulk purchases, warehouse design, membership model, no-frills, great culture, and so on. To top it all off, now that Costco is the second largest brick-and-mortar retailer in the country, they have nearly unrivalled purchasing power with suppliers. In my view, the company has durable competitive advantages that should contribute to continued market share gains for decades to come.

E-commerce will continue to be a strong secular trend, and is the largest risk to the business today. That being said, the company continues to invest in their e-commerce platform which I believe is already a fairly compelling option for large online purchases/basket sizes. The company’s value proposition is ultimately “great value”, not the “convenience and selection” that come with most e-commerce offerings. I believe that this continues to differentiate Costco from other retailers, both brick-and-mortar and online competitors, and believe that the traditional brick-and-mortar retailing approach can still succeed in the face of growing e-commerce penetration.

Revenue growth

I’ve broken down merchandise revenue growth into 3 main drivers (see Exhibit AA): growth in warehouses; members per square foot, and sales per member. All told, I assume that Costco grow’s revenue at a ~7.2% CAGR between 2020 and 2030, and expand on that view below.

Besides a handful of outliers, the company has consistently opened 15-30 warehouses/year over the past two decades. Including 2021, the average has been 20-22 warehouses/year on a trailing 5-, 10-, and 15-year basis. Going forward, I assume that Costco will average ~27 new warehouses/year; see Exhibit AB.

Costco has a large remaining growth runway in the U.S., see Exhibit V. I expect that the company will have at least a single store in every state, and that average penetration reaches ~2.0 warehouses per million people by 2030. For context, this compares to 1.7 and 1.4 in 2020 and 2010, respectively. Costco opens ~15 new warehouses/year over the next decade+ compared to the trailing 10- and 20-year averages of 14 and 15, respectively.

Canada is fairly penetrated today, but I expect that there’s still some room for warehouse growth here. Competition is worse in Canada, and Costco’s relative cost advantage should allow them to continue increasing their penetration, albeit at a slower pace. My guess is ~2 new warehouses per year over the next decade, which would take warehouses per million people to ~2.9 by 2030 compared to 2.7 in 2020 and 2.3 in 2010.

The warehouse model has worked very well in new geographies, and I expect Costco to focus more on expanding their footprint internationally over the next decade. I don’t explicitly forecast new geographies, but my guess is that they can add warehouses in 5-10 new countries by 2030; they’ve proven that their value proposition travels well, and I expect that they’ll ramp this up. I also think it makes sense for Costco to continue expanding in geographies where they’ve had great success, specifically China, France, and Australia. I assume that by 2023, Costco is adding ~7 warehouses/year, which ramps up to ~15 per year by 2030.

Sales per square foot has increased at a CAGR of 3.6% between 2010 and 2020, driven in ~equal portions by growth in members and spend/member. I assume that average product sales per sqft grows at 4.4% between 2020 and 2030:

I assume that the average member/sqft grows at a CAGR of 1.7% over the next decade, compared to 2.0% between 2010 and 2020. Mature warehouses should see a small amount of growth in member-signups, but I mostly expect corporate utilization to improve as the percentage of new warehouses falls (of total warehouses). I also assume that Costco raises the price of the membership fee once in 2023, and again in 2029, but these are relatively small increases, and I don’t expect them to impact membership-signups/renewal rates. See Exhibit AC.

I assume that sales/member grows at a 2.8% CAGR between 2020 and 2030 (or 2.2% CAGR between 2021/2030), compared to 1.7% over the past decade. Higher inflation plays a small role here, but I also expect that Costco continues to gain share of their customers wallet, that third-party sales of Kirkland products continues to grow (e.g. Kirkland sales through Amazon), and that first-party ecommerce sales continue to grow, which includes sales to both members and non-members.

EBITDA Margins

I assume that corporate EBITDA margins expand by ~40 bps over the next decade, reaching ~4.7% by 2030 vs. ~4.2% and ~3.7% in 2020 and 2010, respectively. Lower competition in international markets should result in structurally higher margins here going forward. Competition in the U.S. will remain relatively high, but I expect that margins can continue to expand as Kirkland and ecommerce grow proportionally. I assume that Kirkland makes up ~43% of revenue by 2030 compared to 32% today, and ~20% in 2010. I also assume that ecommerce grows to ~16% of sales by 2030, compared to ~8% today. I expect Canada’s EBITDA margins will benefit from Kirkland and ecommerce sales as well, offset by increasing competition and penetration over the next decade. Corporate EBITDA margins should also expand as the percentage of new stores falls and asset utilization increases, and as growth in the company’s international segment out-paces their North American operations. As a percentage of revenue, I expect international to go from 13% in 2020 to ~17% by 2030.

Capital Spending

I assume that capex per warehouse today is ~$60 mln, and that this inflates at 2.0%/yr going forward; see Exhibit AE. I also assume that Costco spends ~$150-$220 mln/year of growth capex on ecommerce and information systems, technology improvements, and vertical integration. This would be much higher than the average run-rate over the past decade, but I expect much more investment here as retail competition increases in the U.S., specifically from ecommerce players like AMZN. A few examples of other capex might include: warehouse and depot robotics, similar to what Amazon has been able to do in their distribution centers; last-mile delivery services (e.g. Innovel); warehouse modifications to enable drive-through capabilities for curb-side pickup; manufacturing facilities that support their Kirkland brand, similar what they did with chicken; etc.

I believe that Costco will continue to be mostly a brick-and-mortar warehouse retailer. However, I also expect ecommerce to gain some share of their revenue, and expect Costco to build out more distribution capacity. Depots per warehouse will continue to fall as Costco gains better scale economies internationally and expands their footprint in the U.S., but I expect this ratio to eventually plateau. I assume that Costco spends ~$18 bln on new warehouse additions over the next decade, but only ~$800 mln on new depots and distribution centers, and continues to rely on third-party operators which are captured as ROU on the company’s balance sheet.

Tying it all together/Outputs

Overall, my base case assumes that Costco generates ~$105 bln in CFO between 2021 and 2030, and raises ~$20 bln in additional debt, with D/EBITDA leveling out at ~1.25x by 2030. I assumed that Costco spends ~$45 bln organically, and the remainder (~$80 bln) is returned to shareholders through their regular dividend (30%), special dividends (40%), and share buybacks (30%). See exhibit AG for split of cash outflow. It’s possible that Costco increase their focus on M&A going forward; they made two large acquisitions in 2020, which is the first time they’ve executed on M&A in the past two decades+, and they most definitely have the cash to do so. However, given managements commentary around M&A and historical allocation, I believe that major M&A is unlikely, and that special dividends and share buybacks will continue to be a comfortable home for excess cash going forward.

My base case assumptions show that both EBIT and EPS growth falls, but ROIC continues to grow as Costco’s asset bases matures and utilization improves, the company expands into international markets, and Kirkland grows proportionally.

The DCF model gives us fair value of ~$410/share which implies a -10% return at the current price of $460/share. A screen shot of the DCF model assumptions and outputs is shown below in Exhibit AI.

As well, my scenario analysis gives us a range between ~$275-$600/share, which are meant to represent my best guess at the 10th and 90th percentile outcomes. Exhibit AJ shows my assumptions and sensitivity of some high level KPIs. It’s worth noting here that I don’t give Costco any credit for a growing cash position in any of the scenarios; I assume that they return excess cash to shareholders and ultimately earn their cost of capital on this. It’s possible that Costco instead focuses on M&A, which may add some unaccounted option value to the upside. That said, given how large their growth opportunity is, my belief is that if Costco was going to increase their spend, organic capital is likely the highest ROIC/lowest risk spend and would be the most likely home for this, which is reflected in my bull case. Costco also doesn’t have a long track-record of acquiring businesses, management has proven to be relatively conservative as capital allocators, and M&A is very different than organic spending, which leads me to expect that this won’t be front and center.

I also include Exhibit AK to illustrate these scenarios vs. the current price and to help visualize the risk/return potential.

Despite what I believe to be a high quality business, it’s difficult for me to identify where I may have a differentiated view on Costco as an investment. Costco is a well-covered company, and after a few decades of consistent performance, investors seem to get it. Current share price seems to either reflect a more optimistic set of assumptions than I’m comfortable underwriting, or a slightly lower cost of capital; a 50 bps change to my equity risk premium shifts the curve in Exhibit AK higher by $50/share. In any case, I don’t see a great investment opportunity here today and prefer to put Costco on my watchlist.