As always, if you have any pushback, comments, or questions I encourage you to reach out. You can comment below, find me on Twitter, or reach me at the10thmanbb@gmail.com. You can find the full DCF Excel file in the Valuation section.

Introduction to Canada Goose (GOOS 0.00%↑)

I grew up in a small Canadian city that occasionally saw winter temperatures drop below -40°C. I recall times when my eyelids would freeze shut if I blinked for too long. Hell, I’m pretty sure I have permanent frost damage on my feet from playing outdoor hockey on a particularly cold afternoon. Winter. Was. A. Bitch.

Better than most, I appreciate the functional value of warm winter clothing. Whether it’s fleece, wool, or down, all insulating material used in apparel effectively traps air close to the body, and because air is a poor heat conductor it prevents body heat from escaping into the environment. Many of the insulating materials used in apparel are naturally occurring; for example, wool comes from sheep and down comes from birds. There are also plenty of synthetic insulating materials like fleece, which is produced using petrochemicals and spun into fibres that can trap air (just like wool). As it stands today, naturally occurring insulative materials still deliver the best combination of weight, warmth, and comfort. Of those naturally occurring insulative materials, down has the best weight-to-warmth ratio and is widely considered to be the premium insulator for jackets, sleeping bags, comforters, and so on.

The measuring stick for down quality is “fill power”, which is a proxy for how much air a given weight of down can trap. Low-quality down typically has a fill power in the 300-500 range (1 ounce will loft to 300-500 cubic inches), while fill power in the 600-700 range is considered quite good. Down itself is the fine layer of feathers underneath the rough exterior feathers found on birds, and the fill power of down varies a lot depending on what type of bird it comes from. For example, the common eider is a sea-duck that breeds in the Arctic and literally builds its nest with down plucked from the female’s breast – this eider down has a remarkable fill power of ~1,200, which is an evolutionary necessity for a bird that summers in one of the coldest places on the planet. Ignoring the common eider, whose down supply is rare, duck down typically tops out a fill power of 750-800, while goose down tops out at a fill power of ~1,000. As a result, goose down is largely considered the crème-de-la-crème in the apparel industry.

And that brings us to Sam Tick, who started a small Canadian apparel business called Metro Sportswear in 1957. Metro Sportswear initially made wool vests, raincoats, and snowmobile suits for people braving the frigid north. Sam’s son-in-law, David Reiss, joined Metro Sportswear in the 1970’s and invented a volume-based down-filling machine which helped Metro Sportswear graduate into the production of goose-down parkas. With these new parkas, Metro Sportswear created the Snow Goose label.

The early Snow Goose parkas were utilitarian through and through – in fact, the Expedition Parka was specifically developed in the 1980’s “to meet the unique needs of scientists at Antarctica’s McMurdo Station” where the average high never gets above 0°C and the record low was -51°C. It wasn’t sexy, but it worked. The Expedition Parka gained a stellar reputation and ended up becoming the unofficial industry standard for dealing with extreme low temperatures – a reputation that it continues to hold to this day. Metro Sportswear ended up making plenty of other custom parkas for unique circumstances like the one they made for Laurie Skreslet in 1982 when he became the first Canadian to summit Mount Everest. In that case, they had to optimize for more factors than just fill power, like wind resistance and water repellant material. Like the Expedition Parka, Canada Goose still makes the Skreslet Parka which is rated for -30°C and below. For each of these iterations, it’s clear that the Snow Goose brand was built on functionality and quality over aesthetic, with a specific focus on heavyweight down (HWD). Despite the incredible products and brand value they had created, Snow Goose was largely serving a very niche market of scientists and adventure seekers – through the 1980’s and 1990’s they hadn’t cracked the broader consumer market and revenue in 2000 was apparently just $3.0mn. That all changed with David Reiss’ son – Dani Reiss.

Dani wrote a piece in late-2019 for the Harvard Business Review (you can find it here) about how he ended up at Canada Goose and what changed over his 2+ decades at the helm. He also spoke at a Canadian event last year to tell the Canada Goose story (you can find the full video here). I’ll paraphrase a bit, but Dani had no intention of going to work for his father’s business – he graduated with an English degree and wanted to travel the world and write short stories. To help kick-start the funding for that endeavor his father offered him a 3-month job working with the family business. Dani accepted the 3-month offer in 1996, fell in love with their brand, and never left.

In 1998 Dani started attending international trade shows in Europe and Asia. The Snow Goose label was already trademarked in Europe, so they were selling products under a new name: Canada Goose. Dani quickly realized that “made in Canada” resonated with European and Asian consumers, and that Canada Goose was more appropriate than Snow Goose if they wanted to become a globally relevant brand. Shortly thereafter they eliminated Snow Goose, renamed the business, and leaned into “Canada Goose”. At about that time (2001), Dani convinced his parents to let him take over the business and pursue his vision for what the brand could become. With this new freedom, Dani decided to exit the private-label business and focused exclusively on their own branded products. He also committed to always being “made in Canada”, which he felt added a level of authenticity that would contribute to brand value over time.

Despite excellent products and a new brand, Canada Goose still hadn’t cracked into urban centers in any meaningful way. It was still a product that sold into a small niche. That started to change in the early 2000’s when Canada Goose parkas started to show up on the big screen. For the same reason that the Expedition Parka became the unofficial industry standard for scientists and explorers in the arctic, Canada Goose products became the unofficial standard for film crews, actors, and actresses braving cold weather. The 2003 X-Men sequel X2 was partly filmed in Canada during winter, and Canada Goose designed a custom jacket for Rebecca Romijn (Mystique) to wear between shoots because her costume was literally just a layer of blue body paint. Canada Goose also ended up supplying parkas to behind-the-scenes film crews that had to stand around in the cold for weeks on end. Eventually, these parkas gained a reputation within the film industry and ended up on screen in 2004 with Dennis Quaid rocking a Canada Goose parka in The Day After Tomorrow. You can see in Exhibit A the iconic logo plastered on the front of his jacket. Nicholas Cage then wore a Canada Goose parka in the 2004 film National Treasure with the same logo exposure on screen (funny enough, all the good guys wore Canada Goose, and all the bad guys wore a competing brand). Since then, there have been plenty of Canada Goose appearances on film, and many of the actors and actresses that have grown familiar with the brand now don it day-to-day. What I find particularly impressive is that these weren’t paid product placements. This was purely organic exposure, which mattered a lot considering Dani didn’t initially have the budget for significant marketing. I suspect that this exposure played a big role in widening the appeal of Canada Goose products beyond the niche they initially served.

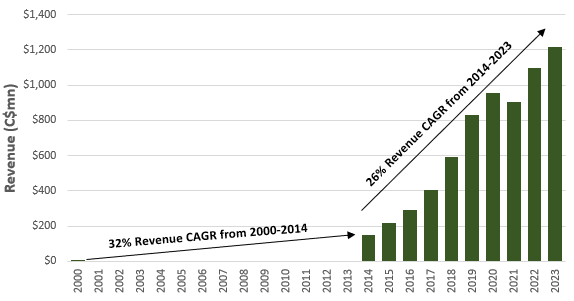

Canada Goose frequently created custom designs for celebrities and then turned those into permanent additions to their product lineup. For example, the ankle-length parka designed for Rebecca Romijn in X-Men’s X2 is now sold as the Mystique Parka. Similarly, they’ve collaborated with other celebrities like Drake and Jose Bautista to bring new products to market – largely HWD and other winter wear. Canada Goose has clearly succeeded at moving beyond their initial niche, and with the help of these collaborations and celebrity exposure is now considered a luxury brand with broader appeal. With that broader appeal, and under Dani’s leadership, sales have increased at a phenomenal rate – from $3mn in 2000 to $1.2bn in fiscal 2023!

Bain Capital bought a majority position in Canada Goose in 2013 to help fund additional expansion, which left Dani as the sole non-Bain shareholder (it looks like the split was 70/30 for Bain/Dani). Canada Goose IPO’d in 2017, but Bain and Dani continued to hold a controlling position (and still do today). Following Bain’s investment, some key things remained the same, like the dedication to being “made in Canada”. Other things changed a lot: they took a business that had historically only sold through wholesale channels and aggressively pursued a DTC strategy; they expanded internationally, particularly in Asia; they acquired a footwear business called Baffin; and they started to introduce Spring/Fall lines to complement their Winter/down collection. Exhibit C breaks out the revenue contribution mix last year by channel, geography, and product category (estimate), and shows the progress made to-date on expanding outside of Canada, opening their own stores, and moving beyond HWD. In my view, there is still a long runway to continue leaning into these strategies, which have important implications for top line growth and profitability, but before diving into each of them in more detail it’s worth expanding on the value of their brand.

The Canada Goose Brand

The only competitive advantage Canada Goose has is their brand – a moat that has taken 66 years to build and reinforce. When I think about brand value, I often circle back to my highlights in Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers (yes, I’m a neanderthal that still uses a highlighter in physical books). Hamilton argues that a brand has value for one or both of the following reasons:

Affective Valence: “The built-up associations with the brand elicit good feelings about the offering, distinct from the objective value of the good. For example, Safeway’s cola may be indistinguishable from Coke’s in a blind taste test, but even after revealing the results, the taste tester remains willing to pay more for Coke.”

Uncertainty Reduction: “A customer attains ‘peace of mind’ knowing that the branded product will be just as expected. Consider another example: Bayer aspirin. Search for aspirin on Amazon.com and you will see a 200 count of Bayer 325 mg. aspirin for $9.47 side-by-side with a 500 count of Kirkland 325 mg. aspirin for $10.93. So Bayer has a price per tablet premium of 117%. Some customers still would prefer the Bayer because of diminished uncertainty: Bayer’s long history of consistency makes customers more confident that they are getting exactly what they want.”

In my view, Canada Goose delivers both affective valence and uncertainty reduction. On the affective valence front, I do think “made in Canada” matters to consumers. All GOOS products are RDS (Responsible Down Standard) certified, the down is sourced through a Canadian-only supply chain, and the core product line-up is all manufactured in Canada. The degree to which that matters probably varies a lot by geography, but it’s undeniably part of the brand value – “after all, who knows cold better than Canadians”. Similarly, it helps that Daniel Craig, Emma Stone, Drake, Ryan Reynolds, Rihanna, J-Lo, and countless other celebrities are seen rocking the Canada Goose logo. That kind of logo exposure adds an aspirational allure to the product, which contributes to a unique sense of identity. Finally, you layer in all the authentic story telling with people like Aldo Kane (who broke a record rowing across the Atlantic Ocean), and the logo starts to represent a way of life more than just a product to keep you warm. For all these reasons, I think consumers are willing to pay more for that Canada Goose logo than an identical unbranded product.

On the uncertainty reduction front, I think many consumers would think of Canada Goose as the OG supplier of parkas for people exploring and living in the coldest places on the planet. These products have been used in arctic exploration for decades, and if it’s good enough for a North Pole expedition, then surely it clears the high-quality bar. Mark Serreze, a climate scientist from the University of Colorado specializing in Arctic research was quoted as saying “my Canada Goose jacket – especially if used with some other underlying layers – would keep me warm on the surface of Mars”. You couldn’t pay for a reputation that good, and it’s something that they’ve been cultivating for decades. But it’s not just this reputation for high-quality performance products – every Canada Goose jacket is hand stitched and passes through 13 sets of hands before it ships. So much attention goes into each jacket that they offer a lifetime warranty to original owners on every single one. There are very few products you can buy with a lifetime warranty – whose manufacturer has that level of confidence in what they make – and I don’t think that goes overlooked by consumers.

When asked about the Canada Goose brand, Dani once commented that “performance, pushed far enough, becomes luxury”. He compared Canada Goose to Land Rover, in that both started as purely utilitarian products that developed a reputation for performance and quality that subsequently turned them into luxury goods. I like that comparison, and as a consumer my perception of Canada Goose is certainly that of a luxury product. Their Langford Parka – something you might commonly see around urban centers and is rated for -15°C to -25°C – retails for C$1,750. By comparison, Mountain Equipment Company (MEC) sells the MEC Guides Down Parka for C$449. That MEC parka has the same down fill power as the Langford Parka and looks awfully similar from afar if you stripped off both logos. If you hold both products up close, it’s easy to tell that the Langford Parka has a better shell, better stitching, and all that jazz. The Langford Parka feels like a higher quality product, and if you pay attention to the details, it does look and fit better (part of the reason might be that MECs parka is made in China). But functionally these two parkas do the same thing. I actually bought that MEC parka 6 years ago, still use it today, and have no complaints. It does the job I wanted it to do. And yet, the MEC parka retails for a fraction of the price. I’m sure part of the price differential is explained by better quality non-down materials, MEC’s cheaper labor, and greater attention to detail (more man-hours going into production), but I suspect that the majority of the price differential is explained by relative brand value. Canada Goose is like the Bayer of parkas while MEC is like the Kirkland.

Brand value should translate into higher average selling prices (ASPs) than comparable products – the brand owner can exercise pricing power. In my view, gross margins are a reasonable – although imperfect – way to assess brand value, so I pulled 2022 gross margins for a range of businesses that compete in the apparel space (Exhibit D). For additional context I also included GOOS gross margins by channel (DTC vs Wholesale). This isn’t a perfect apples-to-apples comparison, but it’s clear that GOOS has gross margins near the high end of the range – just short of some dominant luxury brands like LVMH and Moncler, and much higher than some of the better direct comparisons like Columbia Sportswear.

I think it’s reasonable to infer that GOOS has exercised some of the pricing power afforded to them through brand value. For example, the Langford Parka ASP is roughly 80% higher today than it was in 2015, which works out to just shy of an 8% CAGR. The cost to produce that parka hasn’t inflated at nearly the same rate. As a result, GOOS has experienced gross margin expansion since they started reporting that data in 2014. In fact, Exhibit E shows that if we held the DTC/Wholesale mix constant at 50/50 over time, GOOS would have experienced a normalized increase in gross margins of 8% from fiscal 2014-2023. The data gets a little obscured because they introduced new product lines (like knitwear), but I think the trend is clear. If GOOS hadn’t exercised this pricing power, they’d have gross margins much closer to the middle of the pack (perhaps comparable to Columbia Sportswear once we adjust for the channel mix), and likely wouldn’t have realized any gross margin expansion over the last decade.

I think it’s well established that GOOS has built a luxury brand and benefited from some degree of pricing power as a result. What’s less clear is whether they’ve exhausted that pricing power – can ASP inflation outstrip COGS inflation for another decade, which in turn would lead to continued gross margin expansion? Unfortunately, I don’t think that’s easy to answer, but Moncler may provide us with some hints.

Moncler was founded in 1952 (5 years before GOOS) and named after a small village in the French Alps. The French founders initially owned a boutique producing down jackets for workers to wear on top of their overalls in harsh environments. Like GOOS, this was a utilitarian-first approach. And just as GOOS gained a reputation designing a specialty line (the Expedition Parka) for scientists at McMurdo Station, Moncler designed a specialty line for the alpinist Lionel Terray, and ultimately supplied the parkas for the first ever summit of K2 (the second highest mountain in the world). They went on to become the dominant down parka for European expeditions and the official supplier of the French national downhill skiing team.

Those functional products that initially sold into a niche market eventually gained broader appeal in Milan during the 1980’s, which marked the beginning of Moncler’s evolution into a luxury brand. Just like I’d almost consider it an accident that Canada Goose gained popularity in film, I’d consider it an accident that Moncler gained popularity with Milan’s youth. But in both cases I think Dani’s comment “performance, pushed far enough, becomes luxury” holds true. Even still, it wasn’t until Moncler was acquired by Remo Ruffini in 2003 and moved their head office to Milan that they really pivoted into a luxury brand. Ruffini initiated collaborations with external designers, brought their collections to the catwalk, and expanded into other apparel categories. Both brands are still well known for quality and performance, but I think you can argue that Moncler is more fashion-conscious than GOOS is today - probably a function of being based out of Milan. It looks like Moncler was much earlier than GOOS to expand into other apparel categories, lean into collaborations, marry fashion with performance, and pursue a DTC strategy (taking more control over their brand). For all these reasons, Moncler’s ASPs seem to be ~50% higher than GOOS as we sit here in 2023. That helps explain why Moncler had the highest gross margins in the peer group from Exhibit D – on a channel-mix-adjusted basis Moncler’s gross margins are ~8% higher than GOOS.

GOOS now seems to be taking many of the same steps that Moncler started taking 20 years ago, and given where Moncler’s ASPs are today, I think it’s possible that GOOS still has pricing power to exercise and further gross margin expansion in store (shitty pun intended). I’ll expand on some of those dynamics lower down, but even if pricing power has been exhausted, they still have a very profitable business as is. Return on invested capital (ROIC) averaged 24% from fiscal 2015-2023 and incremental ROIC through that same period was 26% while reinvesting most of their FCF back into the business. If ASPs (in real terms) stayed flat, but GOOS continued to grow units, there should be significant shareholder value creation yet to come. And that brings us to the important pillars of the GOOS investment thesis.

Pillar #1 – International Expansion

GOOS’ geographic exposure has changed significantly since 2014 (Exhibit F). For example, Canada was responsible for 47% of sales in 2014 but just 20% last year, despite Canada revenue growing at a 14% CAGR during that period. APAC, on the other hand, was a negligible contributor to sales in 2014 but made up ~30% of revenue last year.

You’ve probably noticed that revenue from Canada declined during COVID and hasn’t yet recovered – I’ll touch on that dynamic later, but I think it’s reasonable to assume that GOOS has more-or-less reached full penetration in Canada and any meaningful additional unit growth will have to come from abroad.

Exhibit G shows a slide from GOOS’ last investor day presentation that details Fall/Winter unit sales per 1,000 addressable consumers by region, which is measured by domestic consumers with household income >C$100k. You could easily pushback on the relevance of that specific hurdle, but the primary takeaway should be that penetration outside of Canada is some small fraction of penetration within Canada. I don’t agree with how they’ve framed this, which suggests that penetration elsewhere could reach 50% of Canada’s penetration, but I do think there is still plenty of upside in these other markets.

Take the United States for example, where 100mn people live in states that border Canada, and another 20mn live in a non-contiguous state that experiences “real” winter like Colorado and Wyoming. That’s >3x the population of Canada living in a climate where GOOS down jackets would have clear appeal. And yet GOOS’ U.S. revenue was just 40% higher than Canadian revenue last year (up from roughly in-line two years ago). It feels like an impossible task to estimate what U.S. penetration could get to, even within a more appropriate cohort, but it wouldn’t surprise me at all if U.S. revenue eventually ended up being 2-3x higher than Canada (you can see the historical ratio in Exhibit H). That would represent 12-30% upside to GOOS’ total fiscal 2023 revenue if Canada stayed flat from here. For context, when GOOS IPO’d, aided brand awareness was 76% in Canada but just 16% in the United States. When GOOS started their U.S. expansion, they started in the Northeast, and even though total aided brand awareness across the country was just 16%, it was 25% in Boston and 46% in NYC (that probably explains why they opened their first U.S. retail store in NYC). Four months ago, GOOS indicated that aided brand awareness in the U.S. (excluding the Northeast) had reached 40%. That’s a big improvement in just 6 years and helps explains why U.S. revenue has grown so much faster than Canada over that period (8% and 17% revenue CAGR for Canada and the U.S. respectively). At the same time, there is clearly a lot of room to continue improving awareness, which in turn should continue to drive revenue growth.

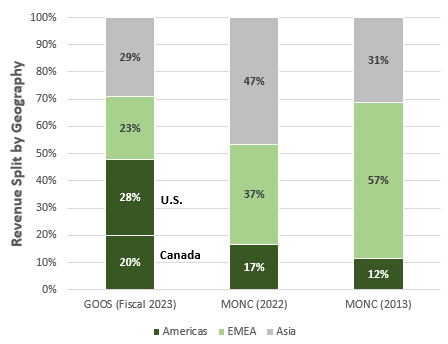

More important than expansion in the U.S. is GOOS’ expansion in Asia, which has been their fastest growing geography by far over the last five years. In Exhibit I, I compare geographic exposure between GOOS last fiscal year (roughly calendar 2022), Moncler in 2022, and Moncler in 2013. It’s no surprise that Moncler, as the home-grown European brand, generated most of their 2013 sales in Europe - just like GOOS, as the home-grown Canadian brand, generated most of their sales in North America last year. What I find particularly impressive is that Moncler grew their EMEA revenue by ~11%/year from 2013-2022 and yet European exposure still shrunk significantly because APAC revenue 6x’d. They’ve clearly found success with their brand in Asia, where there are 3-4 large markets for luxury consumers and an affinity for Western brands. In fact, Moncler’s Asia revenue in 2022 was 2x their total revenue from 2013.

Like Moncler, it’s clear that Asian consumers have an affinity for the Canada Goose brand. In fact, I’ve seen some estimates that suggest 20-30% of GOOS’ Canadian revenue came specifically from Chinese tourists pre-COVID! The company specifically indicates that 40% of pre-pandemic revenue in EMEA came from tourists, where a significant share of that 40% were Chinese tourists. It’s therefore no surprise that GOOS’ APAC revenue has grown faster than any other geography since establishing a physical presence in China, Japan, and Korea over the last 5 years. Even with some early success in Asia to-date, I think the next ten years at GOOS could look like the last ten years at Moncler, where they continue to grow in core markets but expand significantly faster in APAC.

Part of what should drive high APAC growth is opening new retail stores, which is part of the DTC strategy I’ll touch on next. GOOS already has stores in huge markets like Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing, and Tokyo, and in aggregate has 23 stores in China alone. That might seem like a lot, but China has 155 cities with more than a million people. GOOS might not want to be in all those cities, but could they have a retail presence in 50? Sure. Could it be 70? Sure. Even with 70 stores in China, the brand would still be quite exclusive in that market.

GOOS also formed a JV with Sazaby League last year, which was one of their wholesale partners in Japan, and will see a number of new DTC store openings as a result. And in Korea, they signed a new distributor agreement last year and plan to double their retail footprint in the next two years. In many of these markets, GOOS has started collaborating with local designers like Chinese-born Feng Chen Wang to target specific regional tastes. They’ve also started tailoring the product assortment in their online stores so that it better skews to local customers.

Whether it’s new DTC stores, expanded partnerships, local collaborations, or a greater attention to detail on regional SKUs, a lot of energy is being directed toward growing in APAC. It’s also worth noting that a lot of these initiatives are in their relative infancy and seem to have significant momentum. For context, if GOOS’ APAC revenue ended up representing 47% of total revenue (like Moncler today) and there was 0% revenue growth from the Americas and EMEA, GOOS’ APAC revenue would >2.0x and their total sales would increase by 34%. Management is actually guiding to a 4x increase in APAC revenue over the next 5 years, and while I wouldn’t be comfortable underwriting that kind of growth, they clearly have a roadmap to do so.

In my view, the United States and Asia are probably the two biggest opportunities for future growth, but Europe – while potentially less important – isn’t standing still. In fact, GOOS plans to triple their retail footprint in Europe over the next five years. They already have a strong wholesale and online business in Europe, but all those additional retail locations should still move the needle.

I’ll say it again – it’s really hard to predict how penetration outside of Canada will change over time. But as I look at the roadmap, the success they’ve had with international expansion to-date, and analogues like Moncler, I think it’s clear that they have plenty of runway left. Executed well, I can comfortably see a path to GOOS doubling revenue over the next 5 years (call it $1.2bn in additional sales). I don’t think the stock price reflects anywhere near that revenue growth potential today, let alone their guidance for a $1.8bn increase by 2028.

Pillar #2 – DTC

GOOS relied exclusively on wholesale channels through fiscal 2014, and then started dipping their toe into DTC with an e-commerce platform in 2015. In 2017 they opened their first retail stores. Fast forward to fiscal 2023 and two-thirds of their revenue is now coming from DTC channels (e-commerce and brick-and-mortar retail stores). While wholesale gross margins have historically been 45-50%, DTC gross margins are a whopping ~75% because GOOS has one less mouth to feed. Exhibit J shows how much overall gross margins have improved as the DTC channel takes share.

There are of course additional operating costs associated with the DTC channel, like leases and wages of in-store employees, but even after factoring that in, it’s clear that segment operating margins (ignoring corporate costs) are significantly higher in the DTC channel than the wholesale channel (Exhibit K).

Unfortunately, GOOS doesn’t break out e-commerce vs. brick-and-mortar sales or operating margins, but my best guess would be that e-commerce operating margins are in the 55% range using 2015 as the only reference point (they had no retail stores then). Their largest physical stores would have operating margins in the 50% range, and smaller stores are closer to 40%. Regardless of which specific DTC channel they lean into going forward, growth in the DTC mix should be extremely accretive to operating margins. At the IR Day earlier this year, GOOS laid out plans to roughly triple their retail store footprint over the next 5 years – from 51 locations at the end of fiscal 2023 to 130-150 locations by fiscal 2028. In Exhibit L you can visualize what that looks like at the mid-point of the range.

The average retail store is ~3,000 square feet, and management is guiding to sales of ~$4,000/sqft, which gets you $12mn/store/year. If 55-60% of GOOS’ fiscal 2023 DTC revenue came from brick-and-mortar stores (the rest from e-commerce), that would imply roughly $10mn/store last year. Immediately prior to COVID (fiscal 2020) my best guess is that they were doing about $12mn/store. Against that backdrop, their guidance seems reasonable enough. I’m sure that the first 51 stores they opened were in the most desirable spots in the biggest cities, and I have to think that the next 51 stores they open would be slightly dilutive to average revenue/store (all else equal). At the same time, they should benefit from ASP inflation, new product categories, and recovery in foot traffic (I’ll circle back on this in a couple sections). I’d also note that Moncler (adjusting for square footage differences so that it’s apples-to-apples) did about $14mn/store last year and is targeting $16mn/store.

If GOOS succeeds at opening ~90 stores at $12mn/store, that would drive +$1.0bn in top line growth. If we assume that the wholesale channel only grew with ASP inflation, the DTC mix would end up in the 80-85% range (similar to where Moncler is today). Assuming margins otherwise stayed constant in both channels, the mix shift would increase total GOOS operating margins by 4.0-4.5% off fiscal 2023. So not only is the DTC strategy an important part of how they’ll execute on international expansion, but it should also lead to improving profitability/returns.

As an aside, if you get the chance to visit one of the larger Canada Goose stores, it’s a unique shopping experience that I’d recommend. For example, at their Toronto Sherway Gardens location you can try on a coat, grab a drink, and go into their Cold Room; literally a room that drops to -30°C with wind and snow blowing past you. What better way to sell a consumer on the product than really testing it in store?

Pillar #3 – Expanding the Product Lineup

For 50+ years, GOOS was exclusively in the business of heavy winter wear – specifically heavy weight down (HWD) parkas. That started to change under Dani’s leadership. When GOOS IPO’d in 2017, only 15% of revenue came from categories outside HWD. At the time, they had a nascent lightweight down (LWD) business, but very little other apparel, and no footwear. In 2017, GOOS launched their first knitwear collection, and in 2018 they acquired Baffin (a footwear business). By 2019, 19% of revenue came from non-HWD categories, growing to nearly 40% last year. A lot of that mix-shift came from the success of LWD products, which now make up ~22% of the business. These are jackets and vests largely appropriate for -10°C to +5°C and are a natural extension from their core HWD products. Even still, other categories like knitwear, sweaters, and footwear have grown from nothing at IPO to ~18% of revenue last year.

I think there used to be some concerns that gross margins for these new categories would be worse than HWD. Implicitly, that would mean gross margin dilution, but I’ve seen no evidence of that (gross margins in both channels have actually expanded as other categories grow). Part of the reason is that ASPs are high – the plain-looking Huron Hoody retails for C$400. If you told me in 2017 that GOOS would succeed at growing this category with $400 hoodies, I’d have been skeptical… but that’s the power of their brand. To be fair, these other products use high-quality materials, and they make a lot of the non-down stuff in Italy and Romania – so even the perception of quality (manufacturing) should be high. At this point, I think there is clear proof-of-concept.

What I like about the non-HWD categories is that the addressable market is much larger. Not everyone needs a parka rated to -30°C, but orders of magnitude more consumers would don a vest, LWD jacket, hoody, or sweater. Anecdotally, half the people I know with Canada Goose products own vests and sweaters.

Part of why I think GOOS will succeed with international expansion is that they can appeal to a broader set of consumers with non-HWD categories, and they continue to introduce new categories regularly. For example, this summer they’re branching out to shorts, tees, and summer accessories. They’re also looking at eyewear, luggage, duffle bags, and home items like blankets. By 2028, they expect that the HWD category will represent just 50% of revenue, with growth in apparel, accessories, and other to be ~2x higher than HWD. This all feeds into their mission to be an all-season brand.

There is still the risk that category expansion erodes the brand, but I’m not personally too worried about that. Moncler started with HWD but now sells sunglasses, swimwear, fragrances, and polos. They even sell dog coats and accessories. I think there is a clear precedent for moving from a seasonal to an all-season brand, and so long as they continue to approach it at a measured pace and focus on quality/luxury I don’t think it’s likely that they muck it up.

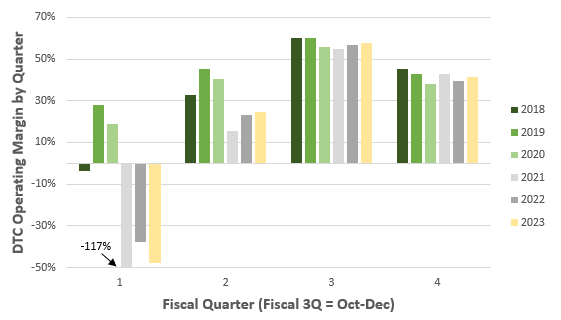

In addition to expanding their addressable market, the move to an all-season brand could improve DTC operating margins. Some portion of store leases are contingent on store revenue, but there are nevertheless fixed costs associated with operating a retail store. If >50% of DTC sales happen in a single quarter – which is the case with GOOS (Exhibit M) – then you could argue that those retail stores are underutilized in the other three quarters.

Because of those fixed costs, it’s no surprise that DTC margins are highest in their 3rd fiscal quarter and lowest (often negative) in their 1st fiscal quarter, which happens to be the middle of summer (Exhibit N). If GOOS successfully transitions into an all-season brand with t-shirts, swimwear, eyewear and the like, then all they really incur is incremental variable costs, which should lead to better operating margins in the 1st, 2nd, and 4th quarters. That’s the theory at least.

I would have expected to see some of that improvement already with non-HWD categories taking share, but it’s important to recognize that a lot of the non-HWD growth in recent years has come from LWD, which should be ~equally seasonal. In any event, if GOOS does succeed at expanding into spring/summer categories, I think it’s reasonable to expect that operating margins from the DTC segment should improve over time. Exhibit O compares total quarterly (GOOS fiscal quarters) operating margins over the last 6 years between GOOS and Moncler. We can see that operating margins between the two are nearly identical in GOOS’ strongest quarter (3rd), but that GOOS loses money in the summer while Moncler still enjoys healthy margins. I think that’s proof that GOOS can be equally profitable as Moncler on a full-year basis if they can successfully pivot to an all-season brand.

The other potential benefit that GOOS would receive from an all-season transition is higher inventory turnover. Instead of stocking a retail store with 80% HWD and LWD jackets 12 months of the year (otherwise they’d be empty), they could rotate in-store SKUs with seasons – at least partially. Again, I’ve seen no real evidence that this has happened yet for similar reasons outlined above, but conceptually I think that’s a fair expectation.

All told, I think the expansion into new product categories helps on multiple fronts, and it’s hard to see how this wouldn’t contribute to meaningful revenue growth, better margins, and higher inventory turnover. They’ve made some headway to-date, proven that it shouldn’t be (too) gross margin dilutive, and still seem to have plenty of opportunity ahead.

Pillar #4 – International Tourism

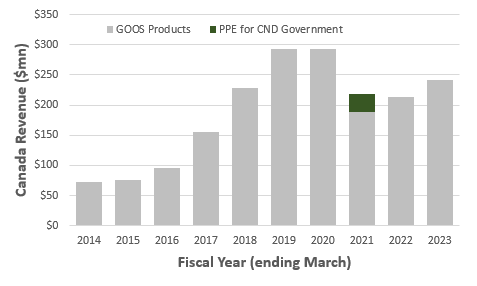

As I mentioned earlier, tourism is an important driver of sales with retail traffic in Europe and North America roughly split “50-50 between local and international consumers” prior to COVID. So, when COVID hit and international travel got decimated, it’s no surprise that more mature markets like Canada saw revenue decline by nearly 40% (Exhibit P; stripping out impact from temporary PPE manufacturing).

While revenue from Canada has recovered a little, it’s still ~20% below the pre-COVID peak, and that’s after three years of high ASP inflation, new product categories, and more DTC stores. In my view, there is still plenty of room for revenue to “normalize”, particularly as international travel recovers to pre-COVID levels.

Exhibit Q shows data from the UN World Tourism Organization and compares international tourist arrivals by region to 2019 levels. Even with activity in calendar 2022 picking up, it was still way below pre-COVID levels, which helps explain why GOOS’ Canadian revenue in fiscal 2023 (roughly calendar 2022) was still much lower than the peak. The good news is that the trend in international travel activity is positive, with 1Q23 within spitting distance of 2019 in Europe and the Americas.

While tourism broadly is important to GOOS, the largest single subcategory that matters is outbound Chinese tourism. In fact, I’d guess that Chinese tourists alone used to be responsible for something like 20-25% of all GOOS revenue in Canada, the U.S., and potentially Europe. Exhibit R was pulled from a Reuters article and illustrates that Chinese outbound tourism, although improving, is still just a fraction of pre-COVID levels.

I wouldn’t necessarily die on this hill, but it seems like eventually Chinese outbound tourism will normalize to something close to 2019 levels. If that happens, then it feels inevitable that GOOS would be a significant beneficiary. Some guesswork is required here, but I think a fair estimate would be that there is $150-250mn of revenue upside if all travel normalizes. That’s 12-20% upside to fiscal 2023 revenue – all else equal. As an aside, I’ll also point out that China’s zero-COVID policy drove perpetual lockdowns until it was lifted in late-2022. Those lockdowns (as recently as GOOS’ fiscal 3Q23 quarter) were a drag on DTC foot traffic in the country, which negatively impacted APAC regional sales. With the policy reversal, GOOS apparently saw 40% y/y growth from Mainland China last quarter. Against that backdrop it looks like the return of the Chinese consumer – both domestically and abroad – could drive significant near-term revenue upside.

Another interesting way GOOS is looking to benefit from tourist spending is a new “Travel Retail” initiative. I’m fairly certain this just means retail locations in airports, which would make a ton of sense:

“We know that luxury consumers travel, and they travel a lot. We also know that traveling consumers often shop our stores. We see an opportunity to have as many as 20 locations worldwide, contributing significantly more than $100mn in the long term”.

Whether it’s the new Travel Retail initiative or just normalization to pre-COVID tourism spending and in-store foot traffic, I think there is meaningful upside to fiscal 2023 sales as the COVID hangover wears off. Again, I don’t think the market is giving GOOS credit for this.

Pillar #5 –SG&A Intensity Normalization

Exhibit S shows SG&A and DD&A as a % of revenue for GOOS and the rest of the comp group in 2022 (using fiscal 2023 for GOOS). GOOS spent proportionally more than anyone else in the comp group last year. As a percentage of revenue, they’re spending 10% more than their closest comp, Moncler.

But it hasn’t always been this way. Exhibit T shows a time series of opex intensity for GOOS, Moncler, and the rest of the peer group, and GOOS actually had opex intensity in-line with the peer group up until the last 2-3 years.

Most of the increase in opex intensity over the last couple of years came from corporate SG&A – stuff that can’t be obviously allocated to the DTC or Wholesale segments like marketing, information technology, product development, strategic initiatives (like the Japan JV costs), or FX gains/losses. Of the incremental corporate SG&A, 25% was marketing spend, 20% was spend linked to new growth initiatives like geographic or category expansion, and 25% was additional corporate personnel costs. It strikes me that a lot of this spend is a precursor to new revenue and shouldn’t scale linearly higher as that revenue materializes. It’s also worth pointing out that GOOS increased corporate SG&A spending by ~$150mn/year since the start of COVID, which coincided with a period where international tourism was kneecapped, and revenue was negatively impacted as a result. Finally, part of the recent increase in corporate SG&A was a non-cash unrealized FX loss on US$ term debt – that’s not a recurring expense. In my view, there are plenty of reasons to expect that SG&A intensity will fall in the future, and if it does, then operating margins could improve significantly.

Exhibit U shows GOOS’ actual adjusted EBIT margin since IPO and then shows what the adjusted EBIT margin would have been if fiscal 2020 (~calendar 2019) corporate G&A intensity had stayed constant through fiscal 2021-23. I don’t know if fiscal 2020 is the right year to benchmark to, but I do feel confident that corporate opex intensity should improve as they continue to scale. I can’t think of a compelling reason why GOOS should structurally have the highest opex intensity in the peer group of nearly 20 other retailers.

Management and Governance

When GOOS IPO’d, Bain Capital and Dani ended up with multiple voting shares, while all new shareholders ended up with subordinate voting shares. Bain and Dani still hold multiple voting shares that entitle them to 91% of all votes and 49% of the economic interest in GOOS. Dani personally owns 20% of the economic interest and controls 36% of the votes.

As it stands, Dani and Bain control this business and everyone else is along for the ride. Overall, I think that’s a good thing. Their combined track record to-date is exceptional. If you ignored the stock price and just looked at business performance – stuff like incremental ROIC, reinvestment rates, change in market penetration, etc. – I can’t imagine you’d have wanted another leadership team at the helm over the last decade. I like the relentless focus on authenticity and quality, and neither party has wavered on what the brand should stand for. The big-picture strategy decisions have all been great like international expansion, the shift to DTC, and introduction of new product categories. Those decisions, so far, have all been followed up with great execution.

The controlling shareholders also seem well aware of where their largest opportunities for growth are coming from, like Mainland China, and preparing the best they can to tap those opportunities. For example, last year they appointed Belinda Wong to the Board of Directors. Belinda was the CEO of Starbucks China during the period where Starbucks China saw a “twelve-fold expansion” in revenue and built a retail footprint of ~6k company-owned stores. That’s a perspective that will likely prove to be invaluable as GOOS looks to do something similar with their Mainland China business.

I also like that Dani is 49 years old. He can clearly make decisions with long-term value creation in mind and can stick around to see the fruits of that labor. In their S-1 from 2017 Dani specifically wrote:

“We are not interested in trading short term revenue opportunities for bad long term business decisions. We are focused on building an enduring brand, a legacy for our employees and our country and long-term value for our shareholders. We have been careful stewards of this brand for 60 years and we will do the same as a publicly-traded company in the years ahead”

For a business whose sole competitive advantage is brand value, I want Dani to run this business – someone who cares more about that brand value than any outsider ever could.

To be my own devils advocate, there are some things I don’t like. For example, they’ve developed a reputation for overpromising and underdelivering in recent years, and their most recent 5-year guidance looks awfully optimistic. To be clear, the business has performed objectively well, but has missed the mark a couple times relative to what management has communicated. Maybe it’s a function of “you manage what you measure”, and if they use an aggressive measuring stick it raises the bar for everyone. At the same time, I could make the case that setting unrealistic expectations could force business decisions that are suboptimal – not just at the CEO level, but for all the direct reports below that as well. For example, if you say you’re going to open 90 new retail stores, you might feel pressured to do so even if the incremental return on stores 70-90 is below your cost of capital. I’m not saying that will happen, but it still strikes me as a risk that you otherwise wouldn’t have to think about without silly publicly-communicated 5-year targets. In short, I’ll never understand the rationale for aggressive guidance, and I’ll never like it as a shareholder.

I suppose you could also argue that if Bain ever chose to exit their position it would create a serious liquidity event. That shouldn’t impact fair value at all, but if you don’t have permanent capital it’s something to think about.

I can nitpick around the edges, but overall, I think the Dani/Bain team have done a great job and I’m happy they’re at the helm.

Financial Position

Exhibit V shows historical leverage metrics and the component pieces of net debt for GOOS at the end of each fiscal year (March).

But recall that this is still a very seasonal business, where non-cash NWC builds through the summer and draws down through the winter. Through that NWC cycle, GOOS draws down on cash and frequently pulls from a revolving credit facility to fund the build in non-cash NWC. Exhibit W shows quarterly ND/EBITDA (with the same lease adjustments as Exhibit V), and we can see that in the first and second fiscal quarters ND/EBITDA routinely hits 1.5-2.0x. Against that backdrop, I’d argue that GOOS is reasonably capitalized and doesn’t actually have a ton of excess cash to return to shareholders today, despite sitting on $300mn of cash at the end of last fiscal year.

The year-round debt almost exclusively consists of a term loan that matures in 2027, and that term loan charges variable-rate interest at LIBOR + 350, which means the cost of that debt is north of 8% today. Not cheap. They’ve fixed a portion of that rate exposure via swaps that terminate in 2025 but are still eating a relatively high interest expense today. If they can’t ultimately roll that term debt into a cheaper facility, I can see a path to GOOS just paying down debt in a few years, and they generate sufficient cash to do so.

Exhibit X shows sources/uses of cash since GOOS IPO’d, and we can see that they’ve reinvested ~70% of CFO back into the business via capex, new leases, M&A, and NWC. That reinvestment drove a 19% CAGR in operating income through the last 7 years, and they still generated sufficient cash to fund $266mn in net buybacks (roughly equivalent to 12% of their current market cap). Looked at through this lens, you could argue that they didn’t even need to take out the term debt that sits on the balance sheet today – they’ve clearly been able to self-fund all their growth. Given the aggressive plans for international expansion, new retail stores, and new product categories, I expect that GOOS will continue to reinvest the majority of cash flow back into the business, but will still be left with some walking around money when all is said and done. If they don’t repay debt, then GOOS will probably continue to repurchase shares under their NCIB. In any event, I think this business is in a strong financial position today with plenty of flexibility.

What happens in a recession?

One concern I’ve come across a few times is what might happen to revenue in a recession. According to Dani, Canada Goose has grown substantially through every recession in company history save for the first wave of COVID (a unique period with retail shutting down completely). I’m not sure that’s totally relevant as the brand matures, but it’s encouraging that they haven’t historically seen revenue decline when consumer spending falls.

I was still curious to see what happened to sales for the comp group that was public through the GFC, so I pulled y/y top-line growth rates from 2006-2012 (Exhibit Y). In 2009, the median y/y change in sales was just -1.2%. On a 2-year basis (from 2008-2010), only two of the fifteen businesses saw revenue decline, and even then the drop in sales was <1%. That’s substantially better than I initially expected to find. Unsurprisingly, luxury brands like LVMH and businesses that were growing quickly heading into the GFC like Under Armour held up better than average. GOOS clearly doesn’t have the same luxury status as LVMH, but it’s certainly more of a luxury brand than Gap or Columbia Sportswear, and those two businesses only saw revenue decline by 2% and 6% respectively in 2009.

As I look through some of these historical analogs, I’ve come around to the view that GOOS’ sales would likely hold up pretty well through a recession. Maybe the growth trajectory gets pushed out a bit, but I don’t think investors need to worry that the business would get impaired.

Valuation

I think it’s helpful to run through a few different valuation exercises:

What is this business be worth if they hit management guidance for fiscal 2028?

What is this business worth in a reasonable no-growth scenario?

What is the market pricing in?

What do I feel comfortable underwriting?

You can find my DCF model below – this version has assumptions that I’d feel comfortable underwriting (scenario #4), but you can play around with the assumptions if you want to run other scenarios like I have.

What is this business worth if they hit management guidance for fiscal 2028?

Fiscal 2028 guidance calls for $3.0bn in sales, up from ~$1.2 last year. Here are some rough assumptions I need to make for them to hit that high bar:

Let’s say the wholesale channel grows at 6%/year over the next five years – that would take wholesale revenue to ~$500mn. So, the DTC channel would have to be doing $2.5bn, up from just $800mn last year – a $1.7bn gap to close.

Maybe they end up opening 90 new retail locations so that they end 2028 at 141 retail locations (roughly the mid-point of guidance). If those stores were doing sales of $12mn/year, that would add almost $1.1bn to DTC revenue. Still a $600mn gap to close.

For the sake of this scenario, let’s assume that the $800mn of DTC sales for fiscal 2023 was 25% lower than “normal” because international travel (in particular, Chinese outbound tourism) still hadn’t normalized. If that normalizes, then maybe the existing DTC business could add $200-250mn to sales, all else equal. Still a $350-400mn gap to close.

We don’t know exactly what the e-commerce split is within DTC, but my best guess is that it was ~$350mn in fiscal 2023 (I basically assumed existing sales per retail store was $10mn in 2023 and subtracted that estimate from total DTC revenue). So, to close the remaining gap, we basically have to assume that either e-commerce DTC revenue doubles, or that ASP inflation over the next five years is mid-to-high single digits.

I’m not saying it’s impossible that they pull this off, but sweet baby Jesus does a lot need to go right. There is very little room for error on execution here.

The second component of guidance is a 30% EBIT margin on that $3.0bn in sales. For context, “adjusted EBIT margin” was 14.4% last year and was 24.9% at the peak in 2019. Moncler, which has the best EBIT margins in the comp group, has a T10Y EBIT margin of 29%, and in their best year exceeded 30% once. Right out of the gate, I think it’s fair to call the 30% EBIT margin guide optimistic. But here’s how they’d get there if – somehow – they pulled it off:

If GOOS hits that revenue guide, then the DTC/Wholesale split would end up at 83/17 from just 66/34 last year. Given how much higher margins are in the DTC channel, that helps with margin accretion.

Even still, I’d have to assume that DTC segment operating margins hit 51%, up from 45% last year but in-line with the 2017-2019 average. To provide some context around that, if the DTC mix shifts from e-commerce to brick-and-mortar retail, operating margins would actually fall because brick-and-mortar margins are lower than e-commerce. And to hit the revenue guidance, I suspect that the mix will shift proportionally toward brick-and-mortar retail. So the only way to see operating margin expansion in that scenario would be for utilization of retail stores to go way up. Implicitly, this means that A) international tourism normalizes, and B) they successfully pivot to an all-season brand in a big way.

Wholesale operating margins would have to improve slightly to 33%, up from 32% last year, but slightly lower than the pre-COVID average.

Corporate SG&A would have to drop from 29% of revenue to 18% - effectively, corporate SG&A in dollar terms grows by just 50% while revenue grows by 150%. In 2018 corporate G&A as a % of revenue was 19%, so I suppose there is some precedent for that level of corporate efficiency.

Again, I’m not saying it’s impossible that they pull this off, but there is literally no margin for error. They need international expansion to work. They need to pivot to an all-season brand. They need to basically triple their retail store count. By my math, if they pulled this off then ROIC would hit ~60%.

Let’s say that post-2028 the business is mature. Unit sales hold flat, and they benefit from some modest ASP inflation – call it 3%/year. If I plug all this into my model with a 3% terminal growth rate, 9% cost of equity, and 7% cost of debt (implicitly a 13.5x terminal P/E multiple), then fair value would be C$71/share. That’s ~3.5x higher than the most recent closing price. Clearly the market has exactly nil faith that they’ll pull this off, and I tend to agree. If I was to probability-weight this scenario, I’d facetiously give it a 1% weighting.

What is this business worth in a reasonable no growth scenario?

In a reasonable no-growth scenario let’s not give GOOS any credit for international travel normalization – the ~$1.2bn of sales from fiscal 2023 is the true run-rate from here. They are currently planning to open 16 retail locations in fiscal 2024 and are aiming for $12mn/year in sales per location, but let’s instead assume they only open 12 new retail locations at $8mn/year. After that, we’ll assume no new retail stores. On the wholesale front, they’re guiding to a 6% decline in revenue for fiscal 2024, so I’ll take that at face value. The net result is fiscal 2024 revenue of $1.35bn, which is below their guidance range of $1.40-1.50bn. Beyond fiscal 2024, we can assume nil unit-growth, but I think it’s fair to give them 3% ASP inflation, which assumes no excess pricing power above inflation. Exhibit Z illustrates what revenue and revenue growth rates would look like using these assumptions. Note that by fiscal 2028 revenue is just $1.5bn, which is roughly half of what they’re guiding to.

On the margin front, since the DTC/Wholesale mix won’t change a lot with those revenue assumptions, I think it’s reasonable to assume that average gross margins won’t change a lot either. Similarly, if there is no international tourist normalization, no change in e-commerce vs brick-and-mortar DTC splits, and implicitly no headway on becoming an all-season brand, I think you could hold both segment and corporate SG&A intensity flat (although you could argue they’d cut some corporate SG&A if this is how the future played out). All that to say, we’d hold EBIT margins flat from fiscal 2023, which means EBIT margins come in at half what they’re guiding to for fiscal 2028. Exhibit AA shows adjusted EBIT margins and adjusted EBIT in absolute dollars using these assumptions. Essentially, fiscal 2028 EBIT comes in at $220mn, which is 75% lower than the guidance they put out earlier this year ($900mn; $3.0bn in sales at 30% margins).

I also assume that capital intensity remains unchanged, inventory turnover stays flat, and their long-term cost of debt is 8%. In the DCF model I use a 9% cost of equity and 2% terminal growth rate (implicitly an 11x terminal P/E multiple). With all these assumptions I still get a fair value estimate of $16/share, which is only ~25% below the most recent closing price. In my view, this scenario is equally unlikely to play out as their guidance. There are just too many positive initiatives that have lots of runway left and a strong brand to help deliver on them. Even still, I think this is a good downside goal post to keep in mind.

What is the market pricing in?

I tweaked assumptions in the DCF model to back into the current share price, and as you can probably imagine at this point, market expectations are pretty low.

For the DTC segment I had to assume that there was no recovery as international tourism normalizes. I assume no unit growth from the existing e-commerce business or retail stores, but do assume 3% ASP inflation. Implicitly, this means that they do not successfully pivot to an all-season brand, and that pricing power (in excess of inflation) no longer exists. I did have to give GOOS credit for some new retail store openings, but assumed they only open 30 new locations vs. the mid-point of guidance through 2028 of about 90 new locations. I also assumed that revenue for existing stores and new stores in a mature state is initially only $10mn vs guidance for $12mn. I grew revenue/store at the same 3% ASP inflation. Exhibit AB visually breaks down the DTC revenue subcomponents that the market appears to be pricing in. In aggregate, this implies a 6.5% revenue CAGR over the next decade vs a T5Y CAGR of 26%.

On the DTC margin front, I baked in 250 bps of operating margin compression. If store foot traffic doesn’t normalize with a rebound in international tourism, then the margin compression GOOS realized since the start of COVID on lower utilization would be permanent. Similarly, if they don’t pivot to an all-season brand then utilization of that retail footprint doesn’t improve. That all contributes to perpetually fewer dollars to cover the fixed operating costs of retail stores. Finally, if brick-and-mortar retail grows proportionally faster than e-commerce then you’d expect some margin dilution. I’ve shown the margin profile in Exhibit AC alongside absolute EBIT dollars in this scenario. EBIT grows at 6.0%/year through the forecast period vs a T3Y and T5Y CAGR of 13% and 23% respectively.

For the Wholesale segment I assumed a 6% decline in revenue in fiscal 2024 and then 3% growth thereafter, which implies that unit sales stay constant, but they benefit from modest ASP inflation. I hold margins roughly flat from last year, such that the EBIT CAGR over the next decade is 2.2%.

I have Corporate SG&A intensity normalizing off the record peak last year. Part of the record SG&A expense last year was attributable to unrealized FX losses on the Term Loan (denominated in US$), which is not a recurring expense. GOOS also added significant corporate headcount ahead of expected international growth, and implicitly the remaining SG&A intensity improvement gives them credit for growing into that “investment”. Even still, in this scenario Corporate SG&A intensity is much higher than the pre-COVID average.

In the DCF model I keep capital intensity and inventory turnover constant and assume that the Term Loan rolls at a similar interest rate. I use a 9% cost of equity and a 3% terminal growth rate (14x exit P/E multiple). All that gets me to a valuation consistent with the current price of ~$21/share.

Combined, Exhibit AF shows revenue, margins, and absolute operating income that seem to be implied by the current share price. The way I see it, the market is willing to pay for some modest DTC store expansion (half of which will occur in the next year), but not much else. No tourism rebound from here, very little international expansion, no credit for expanding into new product categories, no remaining pricing power, and no margin expansion. In my view, these expectations are too punitive.

What do I feel comfortable underwriting?

I think it’s helpful to circle back to the big things that matter, and keep these in mind as I outline what I’d be comfortable underwriting:

International Expansion

DTC Strategy

New product categories – becoming an all-season brand

International Tourism

Scaling into Corporate SG&A

In my view, there are compelling reasons to give GOOS some credit for each of these themes. I do believe that penetration outside of Canada has lots of room to increase, particularly in the United States and Asia. I think the DTC strategy is working and will help GOOS achieve some of those international expansion goals while simultaneously improving margins/returns. Early success in new product categories combined with the Moncler analog suggest that non-HWD categories should become a bigger part of the business, which would drive both revenue growth and segment margin improvement. There is plenty of evidence that suggests travel was well below pre-COVID levels last year, and I don’t think travel is permanently impaired – as travel resumes, I think GOOS will be a major beneficiary. Finally, there are clear reasons why corporate SG&A spend outpaced revenue growth (including some transient non-cash expenses), and I can paint a reasonable picture where that normalizes.

On the DTC front, they plan to open 16 new locations this fiscal year and given that those plans are well underway I think it’s reasonable to give them credit for the full 16 locations. Beyond that, I’d be comfortable underwriting an additional 50 stores: 10 in South Korea and Japan, 10 in the U.S., 10 in Europe, and 20 in China. That would take GOOS to 117 retail locations vs guidance for 130-150, and I assume it takes them six years to get there versus guidance for five. While GOOS is guiding to revenue of $12mn/year for new retail stores, I’m comfortable underwriting $10mn/year in real terms. For context, after adjusting for average square footage, Moncler generated $14mn in revenue per comparable-sized store last year and has a target for $16mn/year. And that’s on >3.5x greater retail square feet than GOOS has today. All-in-all, I don’t think my assumptions here are a stretch.

As I argued earlier in the piece, GOOS has built a valuable brand somewhere at the intersection of luxury and performance. I also think it’s true that their brand has become more valuable over the last twenty years as they’ve expanded outside of their early niche and into urban centers. As a result, they’ve enjoyed some pricing power, and ASPs have historically increased at a faster rate than inflation. When I compared GOOS ASPs to other luxury brands, even those that sit somewhere at the intersection of luxury and performance like Moncler, I’m comfortable assuming that they still have some untapped pricing power. Said differently, I think they can continue increasing ASPs in real terms. I’m shooting from the hip on this one, but if run-rate inflation ended up being 3%, I think GOOS could increase ASPs by 5% for some time. All else equal, I therefore feel comfortable underwriting 5% revenue growth per mature retail store.

On top of ASP inflation, I think GOOS will continue to successfully transition to an all-season brand, and we have line-of-sight on multiple new product categories in addition to traction on recently introduced categories. My best guess is that the apparel and other categories (everything excluding HWD and LWD) generated somewhere around $200mn in sales last year. I think it’s reasonable to expect that unit sales from these non-down categories could 2-3x inside of a decade. That would be additive to same-store-sales growth to the tune of 2-3%/year.

I can’t ignore the data showing tourist arrivals in Europe and North America were still well below pre-COVID averages in 2022 (particularly Chinese tourists). I’ve read transcripts from multiple retailers – not just GOOS – that all flag this as a drag on revenue/store. I wouldn’t pay a ton for that normalization, but it feels fair to give GOOS an extra 5% growth in same-store-sales for the next 2 years. Included in that would be the return of foot traffic in Mainland China with the U-turn on their zero-COVID policy (where half of their DTC stores are). I think you can make the case that a true normalization might look like 10%/year for two years, but because I don’t have a perfect barometer to measure this I’ll err on the side of caution.

Exhibit AG summarizes my assumptions for same-store-sales-growth from existing retail locations broken out by the three drivers outlined above.

Finally, I assume that most of GOOS’ DTC growth comes from new retail location, and that the e-commerce business grows with ASP inflation. Exhibit AH summarizes the DTC revenue estimates I’d be comfortable underwriting.

If I’m right that traffic per retail store improves, then operating margins should also improve because of fixed cost leverage. Similarly, if I’m right that they can continue expanding into new spring/summer/fall categories, then those incremental sales would be margin accretive. In addition, if GOOS can increase ASPs ahead of inflation, then gross margins should increase modestly. All of this would be partially offset by a mix-shift from e-commerce to brick-and-mortar retail. Even still, net-net I expect to see operating margin improvement. I’m comfortable underwriting 250 bps of margin improvement from fiscal 2023 levels, but that still ends up being much lower than pre-COVID margins, so could end up being too conservative. I’ve shown my margin assumptions and absolute EBIT dollar estimates for the DTC business in Exhibit AI.

I’ll keep it brief on the Wholesale business because I think this is becoming a less important part of the story as DTC takes off. We’ve already seen GOOS trim their wholesale partner list, and I think it’s fair to say that they won’t be adding new partners any time soon. If anything, I can see them dropping more partners in the future. I’m comfortable underwriting 5% ASP inflation but unit volume that declines by 2%/year beyond fiscal 2024, and margins that deteriorate slightly. Even if I change these assumptions a little, it doesn’t make a huge difference to valuation, but I’ve illustrated the key outputs in Exhibit AJ anyway.

If I’m right that the DTC business has a long runway for double digit growth, then I think it would be inevitable that Corporate SG&A intensity improves. For fiscal 2024 I strip out the unrealized FX loss from last year, and some of the other items which I suspect were more one-time in nature, but still have modest absolute SG&A growth. During the highest growth years in DTC, I assume GOOS scales into Corporate SG&A, such that Corporate SG&A as a % of revenue returns to pre-COVID levels (Exhibit AK).

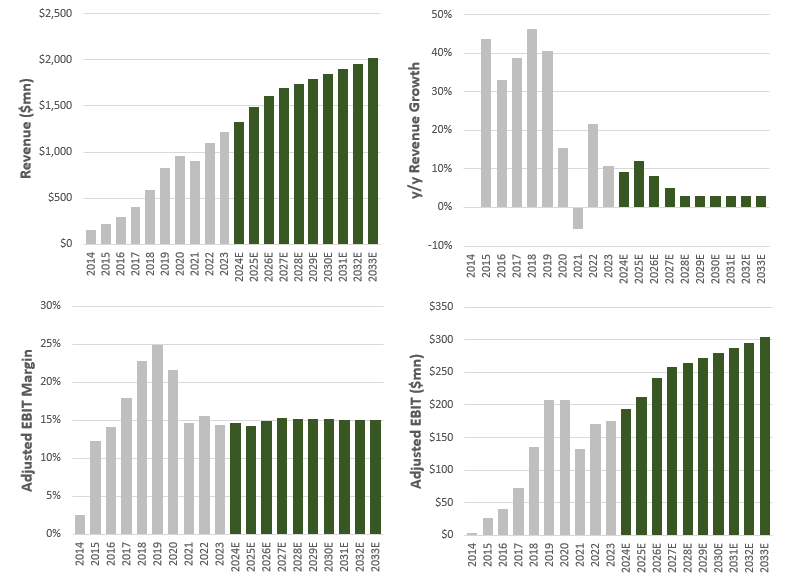

Exhibit AL shows the aggregate estimates I’d be comfortable underwriting for revenue, margins, and absolute EBIT. Note that my fiscal 2028 revenue estimate is 23% lower than management guidance. My run-rate EBIT margin also taps out at 22-23%, which is well short of their guidance for 30%.

You can find the rest of my assumptions in the model, but none move the needle anywhere close to the key drivers above. I’m using a 9% cost of equity, 3% terminal growth rate, and implicitly a 14x terminal P/E multiple. With these assumptions, my fair value estimate is $47/share. That’s more than double the most recent closing price and suggests a 10Y IRR of 21%. Exhibit AM shows a screenshot of my DCF output tab.

Why is stock trading at a fraction of my “base case”?

GOOS is currently down 55% since the beginning of 2022 (at which point it was trading at the fair value estimate I’d comfortably underwrite) and hasn’t traded this low since they IPO’d in 2017. I think part of the reason is that there is investor fatigue. At the beginning of last year, they put out fiscal 2023 guidance calling for $1.3-1.4bn in revenue and adjusted EBIT margins of 19.2-20.7%. They revised down guidance twice and delivered revenue of just $1.217bn and adjusted EBIT margin of 14.4%. A big miss. They’ve been calling out a recovery in foot traffic once international travel rebounds, and it hasn’t materialized yet. Then, at the Investor Day earlier this year, they put out fiscal 2028 guidance that no one seems to believe and even I can’t imagine them hitting. They seem to be in a rut of overpromising and underdelivering – at a very minimum, that’s the perception.

There also seems to be some concern about China broadly. Will outbound Chinese tourism ever recover? Do Chinese consumers still have the same affinity for Canada Goose? What happens to the China business if the political tensions heat up? Admittedly, I’m a tad concerned about that last point, but not the first two. I always get a little uncomfortable when it comes to investing in business with China exposure, but there comes a price where you’re well compensated for that risk.

Finally, I’ve seen some comments from a VIC piece that GOOS is being used on the short side of a MONC/GOOS pair trade, and the last I checked GOOS short interest was a whopping 25% of float (I believe that makes it the most-shorted name in Canada)! The float is small (barely C$1.0bn), but there’s no doubt that this added pressure to the stock price. Outside of the China concern, I haven’t stumbled across any convincing arguments that GOOS would make a good outright short at this price. Given the high short interest and the low implied expectations, I think it’s possible that the slightest amount of positive momentum could quickly move the stock price closer to my estimate of fair value.

Conclusion

In my view, GOOS’ brand is a durable competitive advantage, and one that has contributed to strong top-line growth and exceptional returns on capital. I like that the 3rd generation founder still sits in the CEO seat and has a significant economic interest in the company - he’s likely to be an excellent steward of the brand for a long time. The business has a relatively strong balance sheet, and plenty of capital flexibility to continue pursuing growth initiatives and returning capital to shareholders. I also think it’s true that the luxury-performance brand should prove to be relatively resilient to the ebbs and flows of the economic cycle.

Despite management guidance that has disappointed time and time again, and still seems aggressive, I think it’s clear that the outlook for revenue growth and margin improvement from fiscal 2023 is very strong. Expectations implied by the current share price seem to give GOOS little-to-no credit for most of the major themes I outlined in this piece, which feels too pessimistic to me. There are certainly some risks around the Mainland China business, but it’s my view that this is more than priced in. Finally, given the short interest, I think the slightest positive momentum could quickly close the gap between the current price and the base case value I’d be comfortable underwriting. Alternatively, GOOS could very well buy back a significant portion of float if the share price remained at this level for more than a year.

Given what I view as a fairly attractive risk/reward, I’ve recently become a GOOS shareholder. Even still, I’m actively looking for compelling pushback to the thesis. If you disagree with any of my analysis or views, please fire away in the comments below. You can also reach me on Twitter or the10thmanbb@gmail.com.

Very entertaining read. Thank you.

This is an excellent write up. I had no idea GOOS was publicly traded.

Anecdotally, the brand appears to be growing here in the UK - I know at least 2 people who have bought jackets in the last 3 months.

For a company with a luxury brand/ strong gross margins / owner operator / considerable buybacks it's unbelievable the share price is down 75% in 5 years!

Have you made any further purchases?

Thanks for bringing this to my attention, I'm looking forward to investing further.