I can’t recall exactly what put Ally Financial (ALLY 0.00%↑) on my radar, but it was probably a TSOH tweet, so let’s start it off by giving TSOH a shoutout (you can find him on Twitter, or through his blog).

At first glance, ALLY looks cheap – it’s trading at some mid-single-digit P/E multiple, P/B is amongst the lowest in the “banking” peer group, it looks better capitalized today than at almost any point over the last 20 years, and they’ve successfully pivoted the liability side of the balance sheet toward deposits. Check, check, check, check. So, why does it look cheap?

I think there are a few reasons, but the most obvious is that the market is clearly concerned about auto credit deterioration. It’s also fair to say that net interest margins (NIMs) are going to compress off record levels, at least in the near term. In this post, I’ll dive into the history of ALLY, what the competitive landscape looks like, and attempt to address these concerns. I’ll end it off with what I think the market is pricing in and where I stand.

Full disclaimer: I’m currently an ALLY shareholder, and may increase my weight in the future.

ALLY’s Origin Story

The ALLY story starts in 1919 when General Motors created General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC) to provide financing to their auto customers. For more than half a century GMAC stuck within their circle of competence providing loans - and insurance - to retail auto customers; however, in the late 1900’s they started sowing the seeds of their eventual bankruptcy.

In the 15-20 years leading up to the global financial crisis GMAC acquired several residential and commercial mortgage and related businesses which got rolled up into a GMAC subsidiary called GMAC ResCap in 2005. The following year GM sold 51% of GMAC to a consortium of buyers led by a private equity firm. GM laid out two reasons for doing so at the time: first, GM needed to raise cash to pay for restructuring the rest of their business; and second, they wanted to separate GM’s credit rating from GMAC’s credit rating. GM had just been downgraded and according to Fitch GMAC was at risk of being downgraded “absent any progress or clarity on a partial sale of GMAC”. If GMAC got downgraded, it would increase their cost of financing and compress net interest margins (NIMs) – not great for a lender. So, GM was effectively forced to divest 51% of GMAC in part to stave off a GMAC rating downgrade, which is hilariously ironic with the benefit of hindsight. GMAC was downgraded anyway when the great financial crisis (GFC) hit.

Immediately prior to the GFC, GMAC consisted of an auto lending division, ResCap, an insurance business, and some “other” stuff like resort financing. GMAC ended up converting to a bank holding company in 2008 and would have gone bankrupt if it weren’t for three successive bailouts from the U.S. Department of Treasury. By 2010, the Treasury owned more than 50% of GMAC common stock and had purchased north of $10bn in convertible preferred securities – in aggregate the Treasury invested slightly more than $17bn in GMAC to help it avoid bankruptcy. In 2009/10 the GMAC entities rebranded under the Ally Bank and Ally Financial banners, and ResCap ultimately filed for bankruptcy and separated from Ally Financial in 2012/2013. Some of the “other stuff” also got spun out like the resort finance business, and GMAC ultimately sold or wound down all their international operations.

Ally Financial came public via IPO in 2014 (under the ALLY ticker), and the Treasury ended up walking away with $19.6bn from their $17.2bn investment in GMAC – not a bad outcome for a bailout. This new ALLY was almost exclusively focused on auto lending in the United States. This wasn’t your momma’s GMAC; it was your grandmas.

A Brief Introduction to ALLY Today

Ally Financial (ALLY) is a bank holding company and the parent organization under which all subsidiaries are rolled up. Ally Bank is one of those subsidiaries and is ALLYs wholly owned digital direct bank that accepts deposits from customers and provides traditional banking services to those same customers. For the sake of simplicity, when I refer to Ally Bank in this deep dive, I’m referring to the deposit-taking function that provides funding for ALLY’s revenue-generating business (basically the liability side of the balance sheet). ALLY’s revenue-generating businesses across subsidiaries are divided into five segments: Dealer Financial Services (which is subdivided into Automotive Finance and Insurance), Mortgage Finance, Corporate Finance, and Corporate and Other.

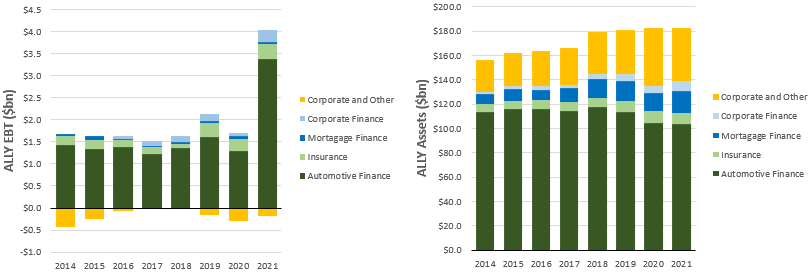

Exhibit A shows ALLY’s assets and EBT by segment from IPO through last year – Ally Bank assets and deposit costs are reflected in these segment results. We can see that the Automotive Finance business has consistently generated ~90% of total EBT – that’s the big thing that matters to any ALLY thesis today. I’ll focus most of my attention in this deep dive on the Automotive Finance business and the changes at Ally Bank but will first provide a brief overview of all the segments below.

Automotive Finance

The Automotive Finance segment can be further subdivided into Consumer Automotive, Commercial (Wholesale floorplan + Other), Operating Lease Investments, and Other.

Consumer Automotive consists of auto loans to retail customers. These are largely indirect loans, which means most of the originated loans come through ALLY’s dealership partners. In recent years, the Consumer Automotive business has generated roughly two thirds of total Automotive Finance revenue. At the beginning of COVID ALLY recorded large provisions for credit losses which didn’t end up materializing. As a result, they recorded very few provisions for credit losses in 2021. This huge swing in provisions – technically a non-cash charge – explains a lot of the Consumer Automotive EBT volatility in 2020/21. I’ll touch on this dynamic and actual credit losses when I circle back to the Consumer Automotive business in another section.

Prior to COVID, the combined Commercial business represented ~20% of total Automotive Finance revenue (I’ll touch on the COVID dynamics later). The bulk of this business is floorplan financing, which is essentially loans to dealerships that are secured by vehicle inventory on those dealer lots. ALLY also provides dealers with revolving credit lines, term loans, and financing for dealership land/buildings.

Operating Lease Investments are exactly what you’d expect – dealerships enter into lease agreements with customers, and then ALLY funds those leases. Technically, ALLY holds the leased asset on their balance sheet and depreciates it over the lease term. At the end of the lease term, one of three things happens: the consumer purchases the vehicle at the stated contractual amount, the dealer who originated the lease buys out the vehicle, or the vehicle is returned to ALLY who “remarkets” it (sells it). ALLY owns a first-party wholesale auction business called SmartAuction and they directly remarket roughly a third of their off-lease vehicles through that channel. If ALLY sells the off-lease vehicle for more than their depreciated cost, they recognize a remarketing gain (and vice versa), which gets included in net revenue.

And finally, in addition to some miscellaneous fees, ALLY collects wholesale auction fees when any of their dealership customers transact on the SmartAuction platform (ignoring the off-lease vehicles ALLY remarkets there).

Exhibit B summarizes total Automotive Finance revenue contributions by subsegment for ALLY’s U.S. operations (prior to 2013 they had some international business which I’ve stripped out). This illustration shows that Consumer Automotive is the largest and fastest growing contributor within the most important segment for ALLY, which is therefore where we’ll spend most of our time in this deep dive. Technically, the Consumer Automotive business would be proportionally smaller as a percentage of EBT, but we don’t have the data to subsegment EBT, and it wouldn’t materially change the importance of Consumer Automotive’s contribution anyway.

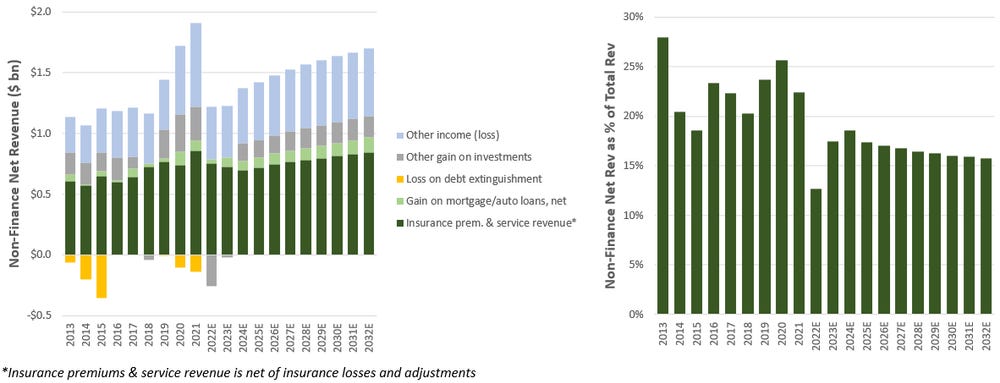

Insurance

The other leg within Dealer Financial Services is Insurance, which is a combination of products sold directly to dealerships and to retail customers of those dealerships. Most of the dealership insurance covers wholesale vehicle inventory, and last year 78% of dealers who utilized ALLY for wholesale floorplan financing also tapped ALLY for insurance on their vehicle inventory. One reason that insurance penetration is so high is that ALLY provides insurance incentives (better coverage at attractive rates) if those dealer customers also utilize an ALLY floorplan facility – this looks an awful lot like a bundle. On the retail side, ALLY provides dealers with vehicle service contracts (VSCs) and guaranteed asset protection (GAP) products, which they can sell to the end customer (and frequently don’t have the scale to offer themselves). Retail VSC’s generate roughly two thirds of total Insurance premiums.

In aggregate, ALLY’s combined ratio in the Insurance business has averaged ~96% over the last decade – which means that 96% of insurance premiums and related revenue are used to cover underwriting losses and overhead (4% of insurance premiums and related revenue flows down to profit). So, while ALLY makes some profit from actual insurance premiums, they make the bulk of their segment profit from investment income on the insurance float. Exhibit C shows historical profit from underwriting and float returns vs the actual float size and return on float.

YTD2022 has clearly been tough with equity and bond markets getting tagged, and the float generated a negative ~3% return in the first three quarters of the year – the first negative year since the GFC. On average, it looks like 15-20% of the float is typically invested in equities, with the rest in a variety of debt instruments (treasuries, MBS, corporate debt). So sure, YTD2022 looks bad, but on balance this doesn’t look like a high-risk float, and I’d expect float returns to be positive (or almost positive) over the next 12 months. Either way, this is a small contributor/detractor to ALLY’s total net income and I see no reason for that to change in the future. If anything, the real value of the Insurance segment is that it compliments their Automotive Finance offering, and by bundling products they can be more competitive in the retail auto lending space. In effect, ALLY becomes this one-stop shop for anything their dealership customers need.

Mortgage Finance

The Mortgage Finance division had something like $80bn of on-balance sheet mortgage loans immediately prior to the GFC (significantly more if you include off-balance sheet loans). ResCap held most of those mortgages, and when they went bankrupt and split off from ALLY in 2012, the Mortgage Finance business all but disappeared.

In 2014, ALLY was left with fewer than $6bn in unpaid principal balances (UPB) in the mortgage book. They didn’t have a direct-to-consumer (DTC) mortgage origination platform at the time, so any mortgage loans they did hold were sourced through bulk purchases from third parties. Ally Home was launched in 2016 as a division of Ally Bank, which gave Ally Bank deposit customers the opportunity to receive mortgage financing – and created a channel for ALLY to originate mortgage loans directly. Ally refers to all Ally Home originations as DTC originations and splits them into two categories: all DTC originations that meet Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac guidelines (conforming loans) get sold and classified as held-for-sale; everything else – which is predominately LMI and jumbo loans – gets accounted for as held-for-investment originations and shows up in UPB balances. DTC originations since Ally Home was launched have grown considerably and helped contribute to UPB growth of nearly 20%/year from 2015 to 3Q22 (see Exhibit D).

You can see from the Exhibit above that there was clearly a ton of refinancing activity in 2020/2021 when rates plummeted and Exhibit E below shows that the weighted average coupon on ALLY’s UPB balances fell from ~4.0% pre-COVID to just 3.2% today on the back of that refinancing. At the same time, the quality of ALLY’s mortgage book seems to have improved with both LTV and FICO metrics for the total portfolio moving in positive directions.

What is ALLY getting from this business with nearly $20bn in outstanding principal balances? Not a lot. The implied net interest margin last year was 78bps. Once we layer in modest gains on held-for-sale originations, and then deduct overhead, ALLY generated a measly $32mn in EBT in 2021 (and only $36mn YTD). By my estimates, ALLY has generated an average ROE of only 6-7% from the Mortgage Finance business since 2016, which is pretty bad when I look at other comps.

In the grand scheme of things, this isn’t a huge drag on total performance considering how small Mortgage Finance is relative to other segments, and I do think there is a path to improved profitability, but that’s deserving of a dedicated section lower down. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with two final observations. First, despite a poor ROE, the traction from Ally Home does contribute to stickier deposit customers that now have a multi-product relationship with Ally Bank. Stickier deposit customers creates an opportunity for ALLY to lower deposit rates (their cost of funding) with less deposit churn, which ultimately improves the economics in other segments. And second, to the extent that the market is worried about credit risk with ALLY, it’s clear that this not a low-quality loan book with an LTV sub-60% and average FICO of 780 - by comparison, Wells Fargo average mortgage FICO as of 3Q22 was roughly 775, and the new mortgage origination FICO for the industry was closer to 750 pre-COVID. If there was a recession tomorrow, I don’t think you need to worry about this blowing up. This looks nothing like ResCap pre-GFC. In fact, since ALLY IPO’d, their Mortgage Finance business has cumulatively generated just $79mn in net credit losses, and even had a few years where they had net recoveries (recovered more than the value of defaults).

Corporate Finance

This is a small but quickly growing and very profitable business for ALLY, which predominately consists of senior secured cash flow and asset-based loans to mid-market companies “owned by private equity sponsors” and loans to asset managers. It’s not immediately clear to me why ALLY is lending into these very specific niches, but it’s obviously very profitable – I estimate that they’ve generated an average ROE in this segment of around 22% from 2014 through today, and that ROE has been reasonably consistent every year. Total finance receivable and loan balances have increased at a 22% CAGR from sub-$2.0bn at IPO to $9.4bn at 3Q22.

We don’t have comparable data to see how these specific loans held up during the last recession, but it’s a very diverse portfolio and net charge off rates are much lower than the auto loan book. In ALLY’s 10k, they specifically mention that one reason they’re growing this business is that it “offers attractive returns and diversification benefits to our broader lending portfolio” even as they focus on “a disciplined and selective approach to credit quality, including a greater focus on asset-based loans”. I suspect that if deposit growth outpaces loan growth in Automotive Finance, more capital will be devoted to places like Corporate Finance. This still only represents 6% of total finance receivable and loan balances, so it’s not currently having a large impact on ALLY’s total profitability, but it certainly doesn’t hurt.

Corporate and Other

Aside from corporate treasury activities and corporate costs, this includes all the other small businesses like Ally Invest, Ally Lending, and Ally Credit Card which are retail products offered through Ally Bank. While Ally Bank has been accepting deposits for decades, they hadn’t rolled out many retail banking products you’d expect a full-service bank to have until relatively recently. We already touched on Ally Home, which is the DTC mortgage business that was rolled out in 2016 and gets included in Mortgage Finance, but Ally Invest was launched in 2017, Ally Lending in 2019, and Ally Credit Card in 2021.

Ally Invest is a digital brokerage and wealth management offering that now has roughly $13bn in net customer assets across 521k accounts on the platform since launching five years ago. Net customer assets fluctuate with market returns, so I think the better KPI to watch is customer accounts. Total accounts have never had a quarter of sequential negative growth since Ally Invest was launched. Ally specifically set out to create a low-cost and commission-free platform, which means that it probably doesn’t generate a lot of revenue (and likely de minimis profit), but it does help make deposit customers stickier by creating another multiproduct relationship.

Ally Lending is their unsecured personal lending business (instalment loans). In the first full year of operation (2020) Ally Lending originated $503mn in unsecured personal loans, which then increased to $1.2bn in 2021, and is on track for about $2.3bn in 2022. ALLY appears to be conservative here as well with origination FICOs in the 735-740 range. Unlike Ally Invest, Ally Lending is likely getting to the point where it’s starting to move the needle – in fact I estimate that Ally Lending generates 50% more EBT than the entire Mortgage Finance business.

Finally, Ally Credit Card was created after ALLY acquired and rebranded Fair Square in December 2021. I don’t have a strong view as to whether the Fair Square acquisition was a good one, but I will note that total cardholders have gone from 693k at the time of acquisition to 1,010k at the end of 3Q22 as ALLY rolls this product out to their deposit customers. That’s nearly a 50% increase in cardholders in <12 months, and total credit card finance receivable balances have increased at a similar rate and now sit at almost $1.5bn. Given the extremely high APRs on credit card debt, this is likely a very profitable business for ALLY, even if you account for high net charge off rates (like Ally Lending, Ally Credit Card is very likely generating more profit than the entire Mortgage Finance business).

In aggregate, Corporate and Other is still a modest net cost center, with profits from these nascent businesses not yet offsetting total corporate costs. However, I wouldn’t expect that to be the case in 10 years, particularly considering that penetration of these products with existing deposit customers is still miniscule - only 9% of Ally Bank customers have a multi-product relationship with ALLY, while the industry average for multi-product relationships is about 35%. This is very likely to be a profitable tailwind for ALLY over any time frame I look at.

Ally Bank

Before I talk about the loan book, I think it’s important to dive into one of the biggest structural changes at ALLY over the last decade, and that’s the evolution of Ally Bank.

Ally Bank is a FDIC-insured depository institution that started as GMAC Bank in 2000 and was rebranded in 2009. Ally Bank is an online-only direct bank – they have no branches, and never have. It astonishes me, but somehow GMAC Bank amassed $32bn in deposits by 2009 (before the rebrand), which made them the 33rd largest deposit-taking institution in the country at the time – all they did was accept deposits. And this was before internet/mobile banking capabilities were even remotely respectable. The only reason I can think of for that early success was that GMAC Bank must have tapped into GM’s 200k+ workforce/dealer network to raise deposits, but that’s still $160k in deposits per employee, which doesn’t make any sense and must mean there was success beyond just GM employees/dealers as well.

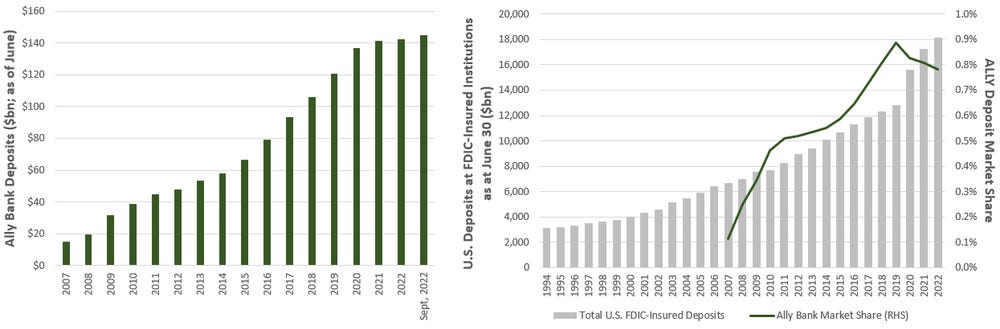

In any event, if GMAC Bank could hit $33bn in deposits (and as far as I’m aware they never had a negative growth year), then it’s not that surprising that Ally Bank, with internet/mobile banking technology improving by an unfathomable amount since 2009, has now attracted roughly $145bn in FDIC-insured deposits. According to FDIC data, Ally Bank was the 21st largest FDIC-insured institution in the country as of June 30, 2022. According to ALLY they now serve over 2.6 million retail customers up from just 1.1mn in 1Q16. Their customer retention rate is 96%, which also strikes me as quite good.

Exhibit F shows Ally Bank deposits over time, total U.S. industry FDIC-insured deposits, and ALLY’s deposit market share. ALLY took significant share in the FDIC-insured deposit market up until 2019, but from 2019-2022 industry deposits grew 42% while ALLY deposits only increased by 18%, leading to some share loss.

There are good reasons that ALLY has taken share in the deposit market during the 10+ years leading up to COVID, and I think the same ingredients still exist for them to continue taking share in the future despite a recent loss of share. First, let me touch on what happened during COVID. I read an article published by the Fed earlier this year that explained the industry-wide spike in deposits (link). They highlight that in 2020:

“banks’ balance sheets saw an unprecedented increase of nearly 90 percent on an annual basis in commercial and industrial (C&I) loans. The counterpart of the drawdown in C&I credit lines was the creation of deposits.”

Eventually, stimulus payments, high personal savings rates, and “federal government loans directly to small businesses” contributed to even greater deposit growth. ALLY would have benefited from some of these dynamics like high personal saving rates, but I think it’s important to note that they largely serve retail customers and are likely under-indexed to commercial/SMB customers. As a result, I don’t think the fact that they ceded deposit share over the last three years is indicative that something is broken – and if I could easily pull retail-only deposits I suspect they would tell a different story. There is also a good chance that total deposit growth turns negative in the coming years for the first time since World War II as some of these dynamics unwind, but since ALLY didn’t participate in the run up of commercial/SMB deposits, I suspect the downside to their deposit levels is relatively small.

With that out of the way, let’s touch on why Ally Bank has historically been able to take share in the deposit market and why I think this will continue. In my view, it all comes down to counterpositioning incumbents. As an online-only bank, ALLY doesn’t spend any money on physical branches, whether that be the actual occupancy expenses or the compensation and benefits to staff those branches. If I had a team of analysts working for me, I’d get them to pull the relevant data for all large lenders, but I don’t, so instead I compare ALLY with JPM (the big-daddy incumbent and the largest deposit-taking institution in the country with >10% share). Exhibit G shows occupancy and compensation expenses as a percentage of deposits over the last decade. The combined delta in occupancy and compensation expenses during the decade leading up to COVID increased substantially – likely as ALLY scaled a fixed cost base over more depositors. I get that this isn’t a perfect apples-to-apples comparison, but I still think it illustrates that an online-only bank can deliver basic account services at a lower cost than incumbent banks with large physical branch networks.

Why does this matter? Well, I think it’s clear that ALLY is sharing these cost savings with consumers by offering higher interest rates on savings accounts/CDs/etc. and lower fees and restrictions on deposit accounts. Exhibit H shows the average deposit interest rate (on U.S. deposits) for JPM vs ALLY since 2010. On average, ALLY has paid depositors about 1.2% more than JPM. In fact, my last check of savings account APYs showed that ALLY is currently offering 3.00% vs JPM at 0.07%. Relative to most large incumbent banks, ALLY also has lower fees and fewer restrictions (like minimum account balances). ALLY can do all this without really sacrificing profitability since they are effectively just passing along cost savings elsewhere in the business (all else equal).

I know that bank customers are notoriously sticky and that an extra 1-2% APY on a competitors savings account isn’t necessarily going to drive a ton of churn at the legacy incumbents. However, I think the evidence shows that it helps at the margin and there is clearly a cohort of customers that are rate sensitive and will choose to bank with ALLY vs an incumbent if it means they get better deposit rates.

It’s also not easy for any of the established incumbents to shutter branches and transition to an online-only model, even if they recognize some of the benefits of doing so. Circling back to JPM, I think they see that they can operate more efficiently with fewer branches, but that’s not a transition that can happen overnight without significant customer churn (many customers, particularly older existing customers, have grown accustomed to branch banking). Total JPM branches fell from a peak of 5,630 in 2013 to 4,790 at the end of 2021 (-15%). They even gained modest share in the deposit market during that period, but this is still a relatively small decline over almost a decade.

We also can’t forget that most of the largest banking institutions in the country are probably riddled to the core with technical debt. As a Canadian, I’m obviously a customer of a Canadian bank. I also worked at a large Canadian bank, and speaking from experience, these institutions are one Excel 93 spreadsheet #REF away from total system failure. It’s like someone started building block 1 of the tech stack in 1980, and every additional block was built on top of the one before, where everything built today needs to be backward compatible all the way to that first block from 1980. Instead of creating totally new systems as technology improved, most banking tech stacks were built on an ad hoc basis. It appears to be a very similar situation in the United States. Many digital banking platforms at large banks just need to be rebuilt from scratch, and some estimates suggest that this would cost hundreds of millions – if not billions – of dollars per bank and cause a lot of headaches during the transition. I suspect plenty of the largest banking incumbents will continue to put this off for years, and/or screw it up.

By comparison, I suspect Ally Bank has relatively little technical debt, particularly considering most of their banking products were launched inside of the last 5-6 years and all those products are digital-only (i.e., digital first and not an afterthought). Technical debt can show up as an implicit or explicit cost. On the implicit side, it can lead to a worse digital experience for customers. On the explicit side, it can lead to a significant portion of technology budgets being diverted away from new products and services to just fixing old bugs. In fact, one McKinsey study found that 20-40% of tech budgets among large institutions (banks, insurance companies, healthcare entities, telcos, etc) was spent putting band aids on technical debt. I’m not convinced that ALLY’s mobile banking platform is that much better than some of the incumbents (implicit cost), but I’m reasonably convinced that they have an explicit cost advantage by not carrying as much technical debt – Exhibit I shows technology spend as a % of deposits for JPM vs ALLY, and while ALLY tech costs have clearly benefited from scale, JPMs have not (if anything, they were getting worse pre-COVID, and recent guidance suggests they will increase substantially again). I get that once again this isn’t a perfect apples-to-apples comparison, but I do believe there is a compelling case to be made that a relatively young digital-only bank has some technology cost advantages over incumbents that they can leverage to take share.

In my view, ALLY should be able to offer better APYs to deposit customers than most incumbents for a long time – perhaps decades. I suspect they will also have a modestly better digital-banking platform than many large incumbents for at least ten years. If these dynamics prove true, then I think ALLY can continue taking share in the deposit market and/or generate higher ROEs over time, particularly if they can successfully expand some of their other banking products. To that last point - when ALLY IPO’d, Ally Bank lacked many of the other products/services that most retail customers seek. They were effectively just a deposit-taking institution. They then launched Ally Home in 2016, Ally Invest in 2017, Ally Lending in 2019, and Ally Credit Card in 2021. Today, retail consumers can manage their investments on the ALLY platform, use an Ally credit card, and get mortgages and personal loans. It’s looking a lot more like a full-service bank today than just an online deposit business. Today, roughly 9% of ALLY’s deposit customers are using other Ally Bank products, up from just 5% in 2019 and 0% in early 2016 (when none of these other products existed) – and compared to about 35% for the industry (by one estimate I stumbled across). The more multi-product relationships ALLY can form, the less sensitive deposit balances should be to changing APYs (basically, customers get more sticky), which could create an opportunity to lower deposit APYs spreads relative to other competitors and lead to improving ROE.

The success of Ally Bank to-date has had a significant impact on the profitability of ALLY overall, primarily by lowering their average cost of funding and contributing to NIM expansion. Exhibit J shows ALLY funding sources over time, and we can see that deposits as a percentage of total funding went from just 7% in 2007 to roughly 81% by the end of 2021. Ignoring equity in the business, deposits now make up 88% of total ALLY funding, largely replacing debt (term debt, securitizations, etc.) as a funding source. Exhibit J also shows that ALLY’s deposit interest expense is substantially lower than other debt financing (even though it remains higher than other banks). As ALLY replaces debt with deposits their weighted-average cost of funding falls and this has already contributed to meaningful NIM expansion over the last decade. Based on this change alone, we should expect that ALLY will be significantly more profitable (higher margins, better ROE) in the future than they were even as recently as 5 years ago. It’s hard to overestimate how important this structural shift has been historically and will likely continue to be in the future.

Automotive Finance

Now for the juicy stuff.

As I illustrated earlier, the primary driver within Automotive Finance is Consumer Automotive. In my view, this business is also the one that spooks the market most. So why don’t we start there.

Consumer Automotive - Industry Loan Growth

Most vehicle purchases are financed today, at least in part. Exhibit K shows total outstanding consumer auto loan balances (both owned and securitized) over the last 70 years, and that total balance is now approaching $1.4tn as of mid-2022.

I’ve been able to clearly identify and measure three primary drivers behind auto loan growth: vehicle price inflation, fleet growth (basically just the number of registered vehicles, which is tied to population growth and vehicles/capita), and average loan duration. In Exhibit L I break out the component drivers of auto loan balance growth by decade, and the yellow bar is effectively the unexplained/unmeasurable contribution to loan growth. If I had to hypothesize, that unexplained contribution is probably largely attributable to a greater share of vehicle purchases getting financed rather than paid for with cash. Some of the early GMAC loans in the 1920’s required 35% down with the delta repaid in installments over the course of just one year. That’s extremely punitive and likely meant most people paid cash for cars. Innovations like vehicle identification numbers (VINs) and the FICO credit scoring system were introduced in the mid-to-late 1950’s, which reduced friction for auto financing – this helped accelerate auto loan popularity (likely contributing to the large yellow bar in the 1960’s). The yellow bar was almost nonexistent when interest rates skyrocketed in the 70’s and 80’s– I suspect fewer people financed auto purchases when APRs were flirting with 20%. Since then, interest rates have been in secular decline, making it more attractive to finance a purchase, and the yellow bar has been a larger contributor to total loan growth. Despite the fact that’s it’s surprisingly difficult to get data on cash purchases as a percentage of total auto sales going back 70 years, I think my hypothesis holds water.

It’s clear from the above exhibits that growth in auto loan balances is decelerating, and when I look out over the next ten+ years I think it’s fair to assume that auto loan balances will probably grow at a much lower CAGR relative to history. Feel free to make your own assumptions and plug that into my model (you can find it here), but here are the assumptions that I feel comfortable underwriting:

Inflation: I’d assume that the run-up in vehicle prices during 2022 normalizes and drags down auto loan balances modestly in the near term. I’d then assume something like 2-3% run-rate inflation from that normalized price.

Fleet growth: Growth in total registered vehicles has decelerated every decade since 1950, and if we assume that vehicles/capita stays constant, then maybe you can peg this to population growth. Population growth is also decelerating, so I’d probably underwrite something like a 0.5% CAGR here.

Loan term: In the 1950’s, the average new vehicle loan duration was ~35 months. That jumped to roughly 55 months by the late 1980’s and stayed around there for almost twenty years. Following the GFC, that crept a little higher, and we’re getting close to 70 months today. One reason that loan duration is getting pushed out is to help with affordability (decrease monthly payments), and lenders seem increasingly okay with that given that the average useful life of a vehicle built today (measured in miles) is more than 2x higher than a vehicle built in the 1950’s. There are arguments to be made that loan duration could go to 80 or 90 months, but personally I’d assume that we’ve capped out – I’d underwrite 0% contribution from extended loan terms.

Other: Admittedly, this is a crapshoot. Average APRs on new vehicle loans have recently skyrocketed. If this is a new normal, I’d assume more buyers at the margin use cash to purchase vehicles instead of relying on financing. I’d also note that something like 85% of new vehicle purchases today are already financed, and something like 60% of used vehicle purchases are financed – there might be some room for greater financing penetration, but I wouldn’t personally bet on it. Fleet turnover also seems to fall during recessions as people drive the same vehicle for longer. I have no idea what’s going to happen here, but I’d underwrite 0% contribution from the other category; in fact, I’m tempted to assume that this other category could end up being a drag on loan balance growth.

All told, I’d think it’s prudent to assume something like a 1.5-3.5% CAGR in industry auto loan balances over the next decade, and maybe use 2019/2020 as the starting point to normalize for the impact COVID has had on loan balance over the last two years (I’ll touch on COVID in a second). An observant reader might say “what, are you crazy!? What about near-term recession risk!? Look at what happened in the 1990’s or the GFC!”. To which I’d respond with Exhibit M.

Since auto lending really found its footing in America, there has never been a period where the rolling 10Y CAGR in auto loan balances was negative, although 2012 was a close contender. I was actually surprised to see that peak-to-trough auto loan balances only fell 11% during the GFC before rapidly rebounding. What’s more impressive is that subprime credit shouldered most of that burden. As far as I can tell, JPM had a reasonably high-quality auto book prior to the GFC, and their auto loan balances only fell 3.8% from peak-to-trough during the GFC. Since ALLY doesn’t really traffic in the subprime space, I think it’s safe to assume that the market they specifically compete in will see less volatility in loan balances than the overall market (including subprime). So yes, auto loan balances can fall in a recession as charge offs increase and new purchases fall, but I’m still of the view that outstanding loan balances (which drives industry revenue) are relatively stable.

The recent impact of COVID and rapid vehicle price inflation is a slightly different story. With average selling prices (ASPs) on used vehicles up something like 50% y/y on a rolling 12M basis, and unit volumes holding up decently, outstanding used vehicle loan balances have clearly spiked. On the flipside, it takes a few years for an auto loan book to roll over, so only a portion of outstanding loan balances are based on these elevated ASPs. I’d also note that new vehicle unit volume has declined while new vehicle ASPs have gone up much less than used vehicle ASPs. There are also plenty of lenders in the used vehicle space that are requiring larger down payments and financing a smaller portion of the total vehicle purchase. For example, KMX used to originate loans with a loan-to-value (LTV) of about 95% pre-COVID, but more recently are in the 88% range. Clearly there are lenders that expect ASPs to normalize and are building in a buffer for expected elevated depreciation on new originations. Overall, there are some puts and takes here, but from the beginning of 2020 through mid-2022 auto loan balances are only up 14%. That’s less than I would have initially expected given the insane inflation in used vehicle prices, but I can now see that there are plenty of offsetting factors at work. So even if used vehicle ASPs fall rapidly in the coming year, I think the downside to auto loan balances is much lower than many market participants think. There is an unusual NCO dynamic at play here as well, but I’ll circle back to that when I touch on ALLY’s business specifically.

Consumer Automotive – Industry Market Share

In my view, there is a large and relatively stable pie here that might shrink slightly in the near-term but should continue to grow at some modest rate for a long time afterwards. So, the next question becomes “how does that pie get divided”. I find it helpful to think about auto lenders as 4 distinct categories: banks, credit unions, captive finance businesses, and everything else. Banks and credit unions are self explanatory. Captive finance businesses are dealer financing groups like Toyota Financial, Ford Credit, and Nissan Finance. And everything else includes stuff like buy-here-pay-here (BHPH) and niche (often subprime) lenders. Exhibit N shows the share of auto originations by subcategory over time (all data is from Experian).

It’s no surprise that captive finance businesses soak up >50% of all new vehicle originations – after all, they own the customer relationship, and are basically getting first dibs on high-quality credit. On the flipside, captive finance businesses are nearly nonexistent in the used vehicle market, which I believe is largely because a significant share of used-vehicle sales happen outside of franchised dealers where the OEM doesn’t own the customer relationship. It’s also no surprise that the “other” category in used vehicles is >30%. According to Experian, the average new vehicle origination FICO is ~720, while the average used vehicle origination FICO is more like 650-660. Some of the largest established lenders completely avoid the lowest-credit-quality borrowers in the used vehicle market, and that opens an opportunity for other lenders (think competitors like Credit Acceptance). Banks and credit unions also capture more share in the used vehicle market, and I’d guess that a part of this is providing loans for private sales, where the buyer just utilizes an existing bank relationship to secure the auto loan. Another potential reason is that banks and credit unions can finance loans with cheap deposits instead of more expensive debt financing that other lenders (captive finance businesses and “other” collectively) must use – all else equal, I suspect that just leads to more competitive rates. Whatever the reason, I think the key takeaways here are that captive finance businesses are well positioned to capture originations in the new vehicle market, but banks/credit unions can still compete effectively in both the new and used markets as a function of having lower funding costs and existing banking relationships with buyers.

The top 10 lenders in 2021 had an origination market share of 44%, and those same lenders had an origination market share of 45% a decade prior. The rank order among those top 10 has changed a little, but it’s largely been the same players for the last decade who dominate in this market (see Exhibit O). Of the top 10 lenders, 6 are banks and 4 are exactly who you’d expect of the largest captive finance businesses. GMAC, as the OG predecessor to ALLY, was likely one of the largest auto lenders in the country (if not the largest) for the 90 years prior to the GFC, which was largely a function of GM having had such a high historical market share in the new vehicle space. Post-GFC, ALLY continued to have a large market presence and has consistently been the first or second largest auto lender in the country.

ALLY’s Consumer Automotive Business - History

GMAC was initially the captive finance division for GM, so it makes sense that GMAC retail auto originations all came from GM prior to the GFC. In 2009, following Chryslers bankruptcy and GMACs bailout, GMAC ironically stepped in to be the preferred lender to Chrysler customers as well. The earliest ALLY data we have is 2012, and in that year nearly 90% of all ALLY consumer auto originations came through GM and Chrysler affiliated dealerships, and most of these loans were for new vehicles. Talk about extreme customer concentration.

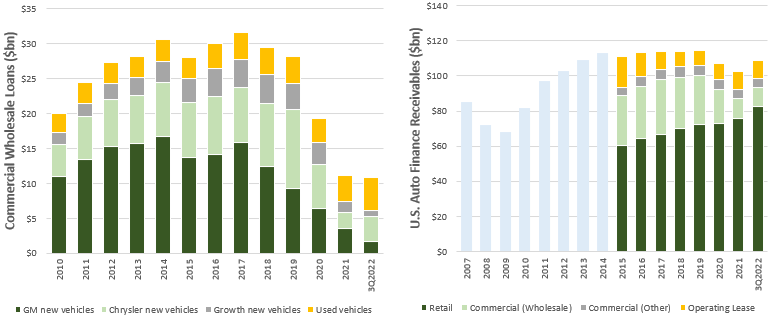

Captive lenders are in a great position to originate loans for themselves – as I’ve already indicated, they own the customer relationship. It’s also a reasonably profitable addition to the core business of selling and servicing vehicles. So, when GM/Chrysler exited that space during the GFC and effectively gave those originations to ALLY, it was only a matter of time before they came back with their own captive finance divisions and took back share. Since most ALLY originations were new GM/Chrysler vehicles in 2012, there was significant risk that ALLY total originations would decline materially over the next decade. In fact, GM got right back into the captive finance game in 2010 when they acquired AmeriCredit and rebranded it as GM Financial. As a result, ALLY’s retail GM originations fell from $23.3bn in 2012 to just $9.6bn by 2021. ALLY is still an important lender for GM dealers, but GM Financial is clearly taking back that share, and I’d expect that to continue (see Exhibit O).

Chrysler was much slower to get back into captive finance. Chrysler ended up partnering with Santander Consumer USA to create a new Chrysler Capital group in 2013, but still leaned heavily on other financing partners like ALLY. In 2014, Fiat ended up acquiring all Chrysler stock and then reorganized as Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA). In early 2021, FCA and the PSA group merged and formed Stellantis, and Stellantis announced later that year that they would be looking to create a U.S. captive finance arm for the combined business. In late 2021, Stellantis acquired First Investors Financial Services Group to kick-start that process. If I had to guess, this new first-party financing division is going to eventually take some share back from the likes of ALLY and Santander, but we have yet to see that happen – ALLY’s originations from Chrysler/Stellantis have remained relatively constant at about $10bn/year over the last decade. Nevertheless, if we use GM Financial as an analogue, I think it’s safe to assume that ALLY won’t be originating $10bn/year of Stellantis loans a decade from now.

So, what happened to ALLY’s total retail auto loan originations as GM and Chrysler clawed their way back into the game? Well, they didn’t drop off a cliff. ALLY breaks out Consumer Auto originations into three categories: GM, Chrysler/Stellantis, and Growth. Exhibit P shows that even though GM originations plummeted, Growth originations have effectively filled the void. Today, more than 50% of ALLY’s total originations come from outside of GM and Chrysler dealers (the most recent quarter was 56%).

Another interesting way to look at this is to add up the market share of Chrysler and GM existing captive finance units, ALLY’s GM/Chrysler business, and ALLY’s Growth segment (see Exhibit Q). The aggregate Chrysler and GM market share (through ALLY and the respective captive finance businesses) has fallen slightly as GM lost market share in actual auto sales but has otherwise remained reasonably steady through time – the only real change is that GM Financial has visibly taken share back from ALLY. I’d also point out that if ALLY’s Growth segment was a standalone business, it would still be one of the top 10 auto lenders in the country today! Origination headwinds are clearly an ongoing concern for ALLY as they cede share back to GM/Stellantis, but the risk of extreme customer concentration diminishes every year that the Growth channel expands.

What exactly is the Growth channel, and why has ALLY been successful at diversifying their business away from two large legacy channels? To start, it’s clear that a big part of the Growth business is coming from the used vehicle market. As a percentage of ALLY’s total consumer auto originations, used vehicles have gone from sub-30% to nearly 70% in the last decade, which coincides with the increase in Growth originations. Back in 2010 when the Growth channel was nascent, ALLY had 12,400 dealership relationships. Today, they have nearly 23,000 dealership relationships, with 16,000 in the Growth channel. Of those 16,000 roughly two thirds are with franchised dealers (Toyota, Nissan, Ford, etc.) and the other third is with non-franchised dealers who would only be selling used vehicles.

Franchise dealers almost all have access to a captive finance unit, and those captive finance units are picking up the crème de la crème of auto loans (I say that a bit tongue in cheek). I quickly skimmed through some captive finance financials, and many of them seem to be originating new loans with very high average FICO scores – for example, the average FICO on originated loans over the last three years at GM Financial, Ford Credit, and Toyota Financial was 721, 746, and 747 respectively. By comparison, Experian shows that the average new vehicle FICO was 721 and the average used vehicle FICO was about 660. For loans that the captive finance unit won’t or can’t compete for (potentially as a function of having higher funding costs), other competitors like ALLY step in. Exhibit S shows T3Y (FY2019-21) origination FICOs for a range of different comps relative to ALLY. There is a little guesswork required here for Wells Fargo and Capital One, but the margin of error should be small. Where many of the largest auto lenders are clearly only accepting some of the highest quality credit, which disproportionately happens to be in the new vehicle market, ALLY has happily competed for more of the average quality credit/used car loans – ALLY’s average FICO on recent originations is more-or-less in-line with the industry average after adjusting for their split of new/used. In my view, this helps explain the success ALLY has had with the Growth segment over the last decade. Similarly, if you recall from Exhibit O above, Capital One gained significant share over the last decade, and their average FICO is even lower than ALLY’s – they also seem to be picking up more average-quality credit that doesn’t get gobbled up by some of the other large lenders. Despite having lower origination FICOs than some of the other large lenders, I think it’s important to recognize that <10% of ALLY’s originations fall in the subprime category – in my opinion, this isn’t a loan book that’s set to blow up in a recession, but I’ll expand on NCOs in another section.

There are good reasons that ALLY has had success in their Growth business, particularly with non-franchise dealers, and I don’t want it to sound like all they are doing is accepting worse credit to grow the loan book. In addition to providing dealership customers with auto financing, ALLY also offers dealership customers floorplan financing, other commercial financing, F&I and P&C products, and access to a first-party wholesale auction platform called SmartAuction. They are doing an excellent job at building multi-product relationships with dealers. They then created a Dealer Rewards program that feeds into dealer loyalty – for example, I think participating dealers that direct more than 25% of their retail auto loans to ALLY (vs other lenders) end up receiving a 50bps reduction in their floorplan financing rates, and I already mentioned that dealers who utilize floorplan financing get preferential insurance products. ALLY also offers cash rewards in a volume-weighted tier system for selling various ALLY products. By my estimate, something like 40% of the 23k dealerships that ALLY has relationships with are participating in the Dealer Rewards program. Dealership customers can also access a digital portal called Ally Dash where they can manage customer communication, wholesale inventory, and financing from a single application. Where auto lending is an afterthought to many large bank lenders, it’s clearly the primary focus for ALLY, and they seem to have built an auto business that can successfully take share in the non-franchise dealer market/used vehicle market. My primary takeaway here is that even though ALLY might continue to cede share back to GM/Stellantis on retail auto originations, their Growth channel is competitively positioned vs non-captive lenders and has a pretty good shot at replacing – if not exceeding – those lost originations. ALLY’s Consumer Automotive business is significantly more diverse today than at any other point in their history, and the risk of losing GM/Stellantis originations is therefore also the lowest it’s ever been. I expect ALLY’s market share in Consumer Automotive to remain among the highest in the auto lending space.

ALLY’s Consumer Automotive Business – Key Drivers

Aside from actual loan balances, which I believe should remain relatively steady over time, there are three key drivers of profitability for the Consumer Automotive business: Net Interest Margins (NIMs), Net Charge Offs (NCOs), and overhead. Exhibit T illustrates what ROE for Consumer Automotive looks like under various scenarios if we flex some of those variables - you can play around with these simple inputs in my model provided above. Using this simple illustration, the steady state ROE in the auto business is somewhere in the low teens range, but a relatively small shock to NCOs or NIMs has a large negative impact to ROE, particularly if we assume that overhead is largely a fixed cost (which the data seems to suggest). That’s clearly what the market is worried about in the near-term.

Net interest margins are a function of interest received on auto loans and the cost of funding those loans. As I already highlighted, most of ALLY’s funding today comes from deposits and the cost of those deposits reprices relatively quickly when interest rates change (this is largely a floating-rate expense). On the flipside, most Consumer Automotive loans are fixed-rate loans, and the loan book seems to reprice (turn over) every 2.5-3.0 years. So, if interest rates fall/rise quickly then auto NIMs will also increase/decrease, and deviate meaningfully from the steady state, at least until the loan book reprices at new rates. I’ll touch on ALLY’s total NIM later, but we’ve seen this play out already with rates falling rapidly through COVID, deposits repricing much faster than the loan book, and record NIMs for ALLY through 2020/2021. Now that rates have rapidly increased, we are starting to see NIM compression, which clearly has investors worried because NIMs could easily fall by 100bps from the peak.

Exhibit U shows historical quarterly NIM for ALLY overall, with Consumer Automotive being the largest determining factor. ALLY is guiding to a 3.5% NIM floor in the near-term and a high-3.0% NIM long-term. I personally think that this is a tad optimistic, and that the downside to NIMs in the near-term could be much worse if rates continue to increase faster than the auto loan book can reprice. By my math, I think it’s totally reasonable to expect that NIM in 4Q22 actually comes in closer to 3.0% than 3.5%. ALLY indicates that 35% of their consumer auto loan portfolio from 1Q22 will have repriced by 4Q22, and 65% will have repriced by 4Q23. So even if NIMs do fall below their guidance range over the next few quarters, I think there is reasonable line-of-sight to NIM-normalization by the end of 2023 – said differently, don’t extrapolate the NIM compression that’s likely to occur over the next 2 quarters if you’re trying to estimate run-rate profitability.

I’m personally of the view that concern about NCOs, particularly in the near-term, is the bigger reason that ALLY looks cheap based on any traditional heuristics. The subcomponents of NCO are gross charge offs and recovery rates. The gross charge off rate is the percentage of auto loans outstanding that get written off (default) and the recovery rate is the percentage recovered on those loans after selling the repossessed vehicles. The net charge off rate (NCO) is the charge off rate after recoveries.

Exhibit V shows ALLY’s Consumer Automotive gross charge-off rates, recovery-rates, and net charge off rates for as long as they’ve explicitly reported the data. It also shows a graph from their 2016 IR Day that shows NCO rates from 2005-2015 excluding Nuvel (a subprime originator). We can see that ALLY’s T4Q average Consumer Automotive NCO rate peaked at a little more than 2.0% during the GFC. ALLY’s Consumer Automotive FICO was 712 immediately prior to the GFC vs just 680-690 today, so while this isn’t a perfect analogue, it’s a good starting point. NCOs as of 3Q22 were still below pre-COVID levels, but those pre-COVID levels were about 50 bps higher than prior to the GFC (explainable by the lower FICO). I’ll reiterate that since ALLY IPO’d they’ve originated Consumer Automotive loans with an average FICO that’s consistently higher than the industry average FICO – albeit by a small margin – and fewer than 10% of their originations are subprime loans. Using the GFC as an analogue, and then adjusting for lower FICOs today, I think it’s fair to assume that if a GFC-magnitude event played out today, then Consumer Automotive NCOs might peak somewhere in the 2.5-3.0% range.

When a loan is originated, ALLY guesses what future NCOs might be and reserves for those through a provision for loan losses, and those provisions are what actually get expensed on the income statement. Provisions that have not yet been realized are accumulated in an allowance for loan and lease loss (ALLL) pool, which is physical cash set aside to cover expected future NCOs. If provisions exceed actual NCOs than the ALLL balance grows – and vice versa.

Despite NCOs today that still look normal enough to me, ALLY clearly expects NCOs to increase in the future (likely above anything we’ve seen post-GFC). As a result, ALLY has been provisioning for loan losses beyond the NCOs they realize, and their ALLL balances have increased – they are setting aside more capital than normal in anticipation of a recession in the auto market. In addition, FASB implemented a new accounting model a couple years ago to measure credit losses called CECL, which resulted in ALLY having to set aside more capital in their ALLL reserve (it’s a more conservative way to account for expected credit losses). The full impact of CECL hasn’t phased in yet, but to-date ALLY has set aside an additional ~$450mn of actual CET1 capital in ALLL because of CECL. The combined impact of over-provisioning and CECL to-date is that ALLY exited 3Q22 with booked ALLL as a percentage of Consumer Auto receivables hitting 2.6%, up from just 1.5% in 2019 (the full CECL change, which ALLY hasn’t yet set aside capital for, would add another ~$900mn or 0.8% to ALLL balances). Starting in 1Q23, that ALLL balance is likely to exceed 3.0% of Consumer Auto receivables (as CECL continues to phase in to CET1). In my view, the growing ALLL balance is a welcome buffer if NCOs do in fact spike over the next year or two. In theory, the CECL method should also lead to countercyclical ALLL balances, where balances as a % of receivables are higher in good times but increase only modestly (or fall) during bad times. Again, this is just the theory, but the CECL method should ultimately reduce volatility in earnings during a recession, which means less downside to CET1 capital when a recession hits. For additional context, ALLL as a % of receivables and off-balance sheet securitizations for Global Consumer Automotive at GMAC were sub 2.0% pre-GFC.

There aren’t a lot of businesses with comparable NCO data going back to before the GFC, but I was able to pull auto NCOs for some large auto lending competitors like JP Morgan, Capital One Auto Finance (back when they reported Auto as a separate line item), Toyota Financial, and CarMax Auto Finance. NCOs for these comparable businesses during the GFC peaked at 1.6-3.2x the average NCO rate ex. GFC from 2004-2019 (where data is available), and outside of Capital One Auto Finance, no one saw NCOs exceed 2.0%.

I’m very confident that ALLY’s Consumer Auto loan book today is better quality than the Capital One Auto Finance book prior to the GFC, and Capital One Auto Finance saw NCOs peak at 4.59% (1.6x their pre-GFC run rate). I feel comfortable suggesting that it’s unlikely we see ALLY NCOs get that high if there was a massive recession tomorrow, particularly in the context of what ALLY realized in the GFC. So perhaps that’s a good doomsday scenario, but a better comparison might be CarMax Auto Finance since they lend on used vehicles with similar or longer loan duration than ALLY and likely with similar FICOs. Prior to COVID, CarMax Auto Finance had similar NCOs as ALLY. If I assume that ALLY’s NCO next year was 2.0x higher than their pre-COVID NCO (vs 1.8x for CarMax during the GFC), it implies that NCOs spike to about 2.6%, or 1.3% higher than ALLY’s 2019 NCO rate. If we look back at ALLY’s ALLL balances as a % of Consumer Auto receivables, they are something like 1.1% higher today than in 2019, and likely to end up being 1.5-1.6% higher by 1Q23. Said differently, it looks an awful lot like ALLY has already set aside the excess capital to deal with one year of GFC-magnitude increase in NCOs.

There are a few reasons why NCOs could be worse than the scenario I just laid out above, and it mostly comes down to the unprecedented volatility in vehicle prices that we’ve seen over the last two years. Used-vehicle prices on a T12M basis were up more than 50% y/y, and ALLY originates more than two thirds of their Consumer Auto loans in the used vehicle market. In effect, ALLY is lending on inflated used vehicle prices, and while they don’t report LTVs it’s safe to assume that LTV probably remained high enough. If used vehicle prices drop back to pre-COVID levels at the exact same time that gross charge-offs increase, then the recovery rate on those loans will fall a lot. In Exhibit Y I illustrate what a “normal recession” NCO rate might look like vs the comparable “COVID recession” NCO rate. If we hold the recovery dollars per vehicle constant, assume the same level of gross charge offs, and assume that 70% of ALLY’s auto loan book is tied to elevated average selling prices, then we can calculate the incremental NCO uplift for a “COVID recession” vs a normal recession due to lower recovery rates. I fixed most assumptions and flexed the NCO rate in a “normal recession” to show what the incremental NCO hit would be from these COVID dynamics. The incremental NCO hit certainly isn’t negligible, but I suspect it’s smaller than many doomsday commentators would have you believe.

In any event, I think the range of possible outcomes for NCOs if there was a recession tomorrow is incredibly wide, but if you put a gun to my head and demanded a 95% confidence interval, I’d probably scream “2.5% to 3.5%!” Whatever the number, I don’t think it makes a major difference to fair value so long as NCOs normalize post-recession and ALLY is sufficiently capitalized to weather the storm.

Commercial Auto Lending

Before I look at whether ALLY is sufficiently capitalized to weather a recession, let’s tie off the auto business with a look at ALLY’s Commercial lending book.

Exhibit Z shows ALLY’s total net finance receivables in their Auto Finance business by subcategory, and while the retail loan book has increased every year since the IPO (with loan balances clearly benefiting from COVID and high ASPs), the commercial book has fared much worse. Commercial Wholesale loan balances (floorplan financing) were more-or-less flat from 2014-2019 and have now dropped by 61% through COVID. All dealerships hold inventory, and they often fund that inventory with floorplan financing (secured by the inventory). Over the last two years, supply chain challenges have led to lower supply of new vehicles, and inventory levels at all dealerships have declined as a result. Since >80% of ALLY’s pre-COVID floorplan financing facilities were for new vehicles, they were hit particularly hard. As we emerge from COVID I think it’s reasonably likely that Commercial Wholesale loan balances improve dramatically (this is an offsetting volume tailwind to the headwind of falling used-vehicle ASPs).

In my view, there is some concern about ALLY’s exposure to $CVNA (an analyst even asked about this on the last conference call). ALLY has historically funded retail auto loans originated through CVNA (I see no risk there), but also currently has a $2.0bn floorplan facility with them. Of the $2.0bn, I believe only $500mn is drawn today, which means only 5% of ALLY’s current Commercial Wholesale loan balances are tied to CVNA inventory, and ~1% of total Automotive Finance loan balances.

There is a real risk that CVNA goes bankrupt, but what then? Well, ALLY’s loan is secured by inventory, so in theory they should be able to sell that inventory and recoup their loan balances. If ALLY is lending at a 100% of the acquired vehicle price, CVNA goes bankrupt, and used-vehicle ASPs fall very quickly, then I suppose it’s possible that ALLY doesn’t recoup 100% of their outstanding loan balances. On the flipside, inventory turns over quickly (sub-90 days) and there is inherently a 10%+ gross profit buffer between the acquisition price and the expected selling price. So, for ALLY to not be made whole, I think used vehicle ASPs would have to fall by more than 10% inside of 90 days at the exact time that CVNA goes bankrupt. There are also nuances to liquidation – or not – depending on whether Carvana filed for a Chapter 11 or Chapter 7 bankruptcy: in the former, there probably wouldn’t be a liquidation event, and ALLY would be totally fine; in the latter, there would definitely be a liquidation event, so you could more easily assume some permanent loss of capital. I’ll admit, there is a lot of uncertainty here and lots of possible futures. The CVNA dynamic should be watched closely by anyone thinking about investing in ALLY, but I’m personally of the view that the risk of loan write-offs from the CVNA floorplan facility in the context of ALLY’s total portfolio is relatively small. If they filed for a Chapter 7 bankruptcy, and had drawn down the entire facility, I’d feel reasonably comfortable assuming that ALLY only writes off a couple hundred million dollars on this facility. At the time of this writing, it looks like CVNA might go the way of Chapter 11 anyway, in which case I really don’t think there is a risk of write-offs from their floorplan facility, and they are likely to continue lending to the new owners.

Capitalization

Ally Financial is a bank holding company with subsidiaries that have FDIC-insured deposits and is therefore bound by all the relevant banking regulations. The most relevant to this discussion are the capital adequacy requirements under Basel III. Most banks must maintain a minimum “Common Equity Tier 1 risk-based capital ratio of 4.5%”. Beyond that minimum capital ratio, ALLY (as a Category IV firm) also must submit an annual capital plan to the FRB and undergo a supervisory stress test on a two-year cycle. The FRB uses this information to set a stress capital buffer (SCB) on top of the minimum capital ratio. In June of 2020, the FRB determined that Ally the parent company required an SCB of 3.5%, which meant that ALLY must maintain a minimum Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio of 8.0% (4.5% + 3.5%). The latest FRB review led them to lower Ally’s SCB to 2.5% effective two months ago, for a total CET1 ratio requirement of 7.0%. If ALLY’s CET1 ratio falls below this level, they are basically prohibited from distributing capital to shareholders via dividends/buybacks. There are other regulatory requirements that ALLY must abide by, but this is the most important one in my view. If they stay on-side here, they’ll stay on-side everywhere.

The CET1 ratio is calculated by dividing CET1 by risk-weighted assets (RWA). CET1 is a function of book value of common equity less goodwill and other intangibles, adjusted for the CECL phase-in and unrealized gains/losses on investments. Net income/loss adds to/deducts from CET1, while dividends and buybacks obviously reduce CET1 – it’s a pretty simple model. Under Basel III, each asset category gets risked at a certain multiplier to arrive at RWA. For example, cash gets a 0% risk weighting as the least risky asset, while auto loans might get risked closer to 100%. If the asset side of the balance sheet is deemed riskier, than risk weights go higher, which increases RWA and reduces the CET1 ratio. You can find all the CET1 and RWA historical data and my forward-looking estimates in the model (link). Basel III implementation started phasing in during 2015, and I used the same framework to calculate pre-2015 CET1 ratios, which required some guesswork to account for the massive off-balance sheet assets that existed prior to 2013. Exhibit AA shows what ALLY’s CET1 ratio would have been from 2007-today under the Basel III regulatory framework (if it had existed over that entire period).

The big thing that stands out is how much better capitalized ALLY is today vs immediately prior to the GFC – their CET1 ratio as of 3Q22 was 2.5x higher than 2007 (before bail outs kicked in). With the 7.0% CET1 requirement that kicked in two months ago, ALLY now has a 2.30% CET1 ratio buffer from which they can absorb potential credit losses and/or distribute capital to shareholders. And that’s in addition to the growing ALLL reserves they’ve set aside in recent years. The risk of a catastrophic blow-up from ALLY (or most other lenders) seems de minimis today when comparing to the financial position of most lenders prior to the GFC.

I’ve seen some people point out that ALLY’s CET1 ratio is lower than many competitors today, and then use that as an argument that ALLY is poorly capitalized. In Exhibit AB I show CET1 ratios as of 3Q22 for the largest lenders in the country (and many of the largest auto lending competitors) relative to the regulatory requirements established for October 1, 2022. It’s fair to point out that ALLY’s absolute CET1 ratio is lower than many of these comps, but their CET1 buffer (actual CET1 less the regulatory requirement) of 2.3% looks strong – they have the 4th largest buffer amongst these lenders. It’s this excess capital that needs to absorb credit losses and/or can be used to grow the loan book and return capital to shareholders. Looked at through this lens, I’d argue that ALLY is in a relatively strong capital position today. If NCOs increased at a similar rate across all lenders, ALLY wouldn’t be the first to face capital challenges. Of course, this assumes that the FRB approach to setting SCB and G-SIB buffers is a good approximation of risk to the respective loan books, but I think that’s a reasonable assumption to make given how cognizant of risk the FRB must be following the GFC.

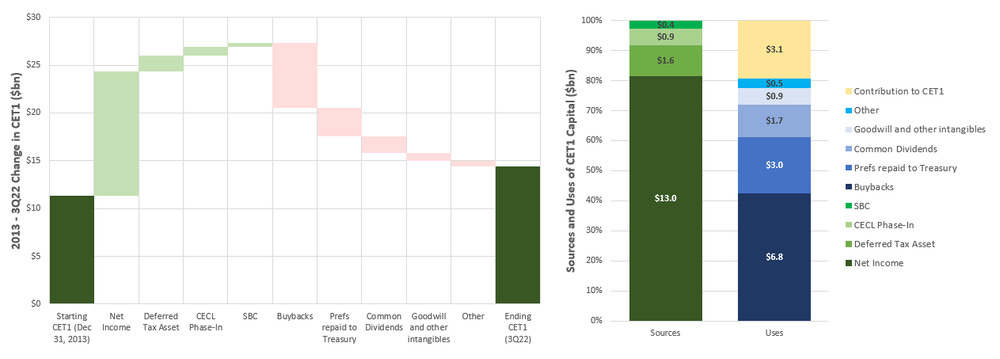

Capital Allocation

Exhibit AC below shows the cumulative change in CET1 capital and the contributing factors from year-end 2013 through to last quarter. ALLY’s CET1 ratio is more-or-less flat over that period, but they’ve had to add about $3.1bn to CET1 capital to cover growth in RWAs. You can think about this as “growth capex”. ALLY did get stuck with a one-time outflow for the repurchase of preferred shares held by the Treasury Department in connection with the GFC bailout, but that more-or-less offsets the cumulative CET1 uplift they’ve received from the drawdown of deferred tax assets, SBC, and the CECL phase-in allowance. On both sides of the ledger, I’d suspect these offsetting items are largely one-time in nature. Goodwill and intangible balances have also increased modestly on the back of M&A (to help build out core banking functions). Even still, of the $13bn in net income they’ve generated over the last 8.5 years, roughly 65% has been distributed to shareholders (they’ve reduced their share count by 30%), with effectively all the remainder reinvested back into the business via growing CET1 balances and modest M&A.

While buybacks have been a meaningful use of excess liquidity in recent years, ALLY’s CFO explicitly stated on the 3Q22 conference call that buybacks are likely to fall materially in the fourth quarter “given heightened macroeconomic uncertainty”, and their focus “on maintaining prudent capital levels amid continued uncertainty”. If ALLY sees NIMs compressing and NCOs increasing, I think it’s reasonably likely that ALLY pauses buybacks beyond just the fourth quarter, even as they are likely to continue generating positive net income. The net result should be an increase in ALLY’s CET1 capital in the immediate future, which will provide a greater buffer in the event that we get a recession in 2023.

Can ALLY manage recessionary NCO/NIM scenarios?

I think we’ve covered enough bases to tie it all together and look at what ALLY could withstand in a near-term recession on the NCO/NIM front.

We can start with ALLY’s last reported CET1 ratio of 9.3% from 3Q22, and then take consensus net income less dividends for 4Q22 to get an ending 2022 CET1 ratio of 9.44% (assuming they pause buybacks). For the next two years (2023 and 2024) we can make modest positive adjustments for SBC and ALLL reserve normalization, and then deduct common dividends, preferred dividends, and the impact of full CECL phase-in. This gets us to the January 1, 2025, CET1 ratio of 8.71% assuming ALLY generated exactly zero net income through full-year 2023 and 2024.

I’ve shown the CET1 evolution using the adjustments above in Exhibit AD. If ALLY had a CET1 ratio of 8.71% on January 1, 2025, and the loan book was otherwise flat during this period, then they would have a CET1 capital buffer of roughly $2.25bn above the 7.0% regulatory requirement. In other words, ALLY has the capacity to absorb $2.25bn in losses (negative net income) over the next two years before they’d have to cut their dividend.

From there, I created a sensitivity table in Exhibit AE to show how the CET1 ratio by January 2025 changes for a range of NIM and NCO assumptions for 2023/2024, assuming ALLY pauses the buyback program for that entire period. What I find remarkable is just how bad things need to get for ALLY to breach the regulatory requirement of 7.0%. For example, if ALLY generated an average NIM of 2.75%, they’d need to see average Consumer Automotive NCOS of 5.0% for two years in a row to run into trouble. Not only would that be the lowest NIM ALLY has seen since IPO (and way below guidance), but it would also be an NCO rate that’s 3.5-4.0x higher than pre-COVID NCOs (both on Consumer Automotive and Total ALLY), and 2.5x higher than ALLY saw during the GFC. And if you recall my earlier comparison to Capital One Auto Finance, JPM, Toyota Financial, and CarMax Auto Finance, that would be a higher NCO rate than any of those businesses saw in their auto books at the peak of the GFC! While nothing is impossible, I’d facetiously peg the probability of this happening at <1.0%, particularly considering that if a recession didn’t start today ALLY would continue to add CET1 capital via positive net income in early 2023.

If I were to be conservative within reason, maybe I’d throw management NIM guidance out the window and assume 3.0% instead of 3.5%. I’d also double ALLY’s pre-COVID NCO rate and layer in some of the COVID-specific tailwinds I highlighted earlier, which is roughly what we saw across other comps during the GFC (if not a tad punitive), and maybe toss in some modest write-downs for CVNA. That would take NCOs to about 3.25% for Consumer Automotive and 2.2% for the total business. In that scenario, ALLY generates negligible net income for the next two years. Does that suck? Absolutely – it means zero buybacks for the next two years and only modest buybacks in 2025 as they rebuild the capital buffer. But does that give them plenty of breathing room above the regulatory floor – you bet. Even if the SBC requirement moved back to 3.5% (which I don’t see as very likely), you’d need to make some very punitive assumptions before ALLY started bumping up against that regulatory floor.

You can find all my assumptions in the model provided above, and I encourage you to play around with different scenarios to see how the CET1 ratio changes (I’ve attempted to make this as intuitive as possible). Whatever you assume, I think the data clearly supports the thesis that ALLY has ample capacity to weather the storm should a big recession hit in 2023.

Mortgage Finance

If you can wrap your head around the near-term recession risk, then you can start to look out further at how ALLY might change in the future, and one area of the business that the market might be sleeping on is Mortgage Finance.

The Mortgage Finance business is largely immaterial to near-term results and the credit loss scenarios I just discussed, but I do think that there is lots of potential here to both A) grow this business, and B) improve profitability. As I already highlighted, ALLY has historically generated what can only be described as a bad ROE in this segment relative to other banks - ALLY’s Mortgage Finance ROE has averaged roughly 6-7% since 2014 while most large lenders seem to have generated an average comparable ROE over the same period that was at least 2x higher.

I think one reason is that they’ve partnered to deliver on Ally Home rather than undertake the entire endeavour themselves – and that partner clips a fee a long the way. That partner, Better Mortgage Company (BMC), does all the selling, processing, underwriting, and closing for Ally Home, so all ALLY does is set loan pricing. In addition, all conforming loans that get originated are sold back to BMC who in turn sells them to Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, and obviously keeps some of that “gain on sale” for themselves.

ALLY, through Ally Ventures, acquired a stake in BMC in 2019 when they officially entered into a partnership agreement with the company (although it seems that they were using BMC – officially “a third-party fulfillment partner” – since launching Ally Home in 2016). I believe the total investment was $26mn. In 2021 Ally Ventures sold 27% of their investment for $45mn representing a total realized gain of 73% on the total investment. Later that year BMC announced plans to go public via a SPAC merger, but those plans have been pushed back a few years. BMC also seems to have faced some liquidity challenges and laid off thousands of employees and has otherwise received some bad press regarding business practices. I don’t know for sure, but my best guess is that ALLY contemplated eventually acquiring all of BMC when they made that first investment in 2019, and then using BMC software as a core building block in their Ally Home platform. But that’s clearly no longer on the table. At this point, I think it’s reasonably likely that ALLY looks to either build out these services in-house or make another acquisition. Either way, I’d be surprised if they were still leaning on a partner in 5+ years to power Ally Home, and if they take on those responsibilities themselves, I suspect that will translate directly into improved ROE.

Another reason that I believe Mortgage Finance is generating below-average ROE today is that ALLY appears to have taken a reasonably conservative approach to origination with average FICOs in this book upwards of 770 since they IPO’d (and 780 today). I suspect they can move down the credit spectrum slightly without seeing an offsetting impact to NCOs. I think ROE can also improve if ALLY originates more loans through the DTC channel and relies less on bulk purchases (which have an implicit cost).

Finally, the overhead ratio in Mortgage Finance (total non-interest expenses divided by net revenue) has averaged 77% since launching Ally Home in 2016 and was 86% last year. By comparison, the overhead ratio within comparable divisions of some large banks is closer to 50%, and the overhead ratio in ALLY’s Automotive Finance business has averaged just 42% since IPO. Part of the elevated overhead ratio in Mortgage Finance is attributable to the fees paid to BMC, but I suspect that even if we strip that out the Mortgage Finance business would have a higher overhead ratio than comparable businesses. In my view, there are probably some modest scale benefits here if Ally brought all Mortgage Finance function in-house (they’d have some fixed technology investments, but that could get spread out over a larger loan pool if this business scaled).

Admittedly, it’s not clear if ALLY would succeed at building the software required to manage Mortgage Finance completely in-house, but if they did, I think we could see ROE in this business more than double. And if ALLY can continue to increase penetration of traditional banking products like mortgages with their large and growing deposit customer base, then we could also see very strong loan growth alongside improving ROEs. I probably wouldn’t pay for any of this today, but it’s still an interesting angle to monitor if you follow ALLY.

Management and Governance